Many things happen around the world. However, most of them are only reported in fragments, and the world visible through the news is very limited. So how does this unreported world come into being? On what basis do the media decide whether to report something? There is research that divides the factors that determine the importance of news into ten (※1), such as whether elites appear, whether there is an element of surprise, and whether it is relevant to the audience. News organizations have a tendency to determine news value with these in mind. In this article, we look at elites among these factors.

In Japan’s international news coverage, there seems to be a tendency to judge as important those issues that people and organizations with significant influence—such as government officials and international organizations—bring to the fore. Let’s look at analyses previously covered by GNV. Coverage of the plastic issue—an environmental problem that has only relatively recently drawn attention—was extremely scarce until the 2018 G7 summit. And while the term Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was not widely reported in 2015 when it was adopted at the UN, coverage increased after the Japanese government promoted it at the UN High-level Political Forum in 2017. Looking at poverty in Africa, the volume of coverage spiked only around the 2005 G8 summit when the issue was emphasized. Moreover, a curious phenomenon was observed in which coverage declined after 2005 even though poverty worsened.

In none of these cases did the problems arise at the time coverage increased. Nor are they topics that can only be reported at such moments. In each case, they were serious issues or important arrangements that existed long before the uptick in coverage. These are topics that affect people actually suffering harm and are also relevant to people living ordinary lives, so there should have been many angles from which to report them. Yet in reality, it seems that they were scarcely reported unless they coincided with events that drew interest from influential countries. What, then, is the relationship between reporting and those with influence—the “elites”? This is the theme of this article.

Informal meeting of EU leaders (Photo: European Council / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Reporting in other countries and elites

The relationship between reporting and elites seen in Japan’s international coverage also appears in reporting elsewhere. Before looking at that, let’s clarify what we mean by elites. Whether someone is an elite is determined by economic, political, and cultural relationships. For example, the United States and China, with their large economic influence, are elite states. Members of parliament and bureaucrats, who have great political influence, can be considered domestic elites. News outlets with large circulations, established reputations in political and business circles, and long histories can also be considered elite. With this in mind, let’s look at reporting in the United States and France.

First, consider U.S. reporting. A frequently cited case in which the media’s role drew great attention is the Vietnam War. There is a view that the media conveyed vivid information through photos and live coverage, fueling the antiwar movement and making it difficult for the United States to continue the war. At first glance, this looks as if the media recognized the problems of the Vietnam War on their own and, by the power of journalism, stopped the war in opposition to the elites.

However, there is research showing that antiwar reporting did not begin spontaneously in the media; rather, it started when some members of Congress began to question the president’s prosecution of the war and antiwar voices grew within Congress. In other words, what became a topic in the elite arena of Congress served as the trigger for antiwar reporting. Conversely, issues that are not discussed among elites tend to be underreported. It seems that news organizations, rather than proactively gathering information, often wait for information to be supplied by elites such as the government and then imitate the issue frames set by those elites.

Next, France. In 2018, a civic movement called the Yellow Vests spread across the country. The movement began in 2018, primarily among those protesting the rising cost of fuel. Online media and local news outlets started covering the movement around mid-November, when it began. Elite media in France, however, first covered it in December, when demonstrators damaged the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

Participants in the Yellow Vests movement in Paris (Photo: Olivier Ortelpa / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

What is noteworthy here is that France’s elite media did not cover the citizens’ demonstrations until they approached the capital, which is of high interest to those outlets. According to one study, news without elites tends not to be reported unless it involves negative or unexpected circumstances. In this example, the sensational damage to the famous Arc de Triomphe in Paris would count as an unexpected circumstance. Conversely, without something unexpected like damage to the Arc, the elite media might never have covered the Yellow Vests movement.

There is also the problem that poverty itself is hard to cover. Because news producers tend not to imagine people in poverty among their audiences, the poor are often separated from other groups that gain attention and thus become harder to report on.

Differences in reporting also appeared. Non-elite outlets such as online media and local news focused more on the movement itself—its demands and participants’ views. Elite media, by contrast, focused on the movement’s impact on politics, paying more attention to the elite world than to the actors in the movement. This tendency for reporting to align with elite interests is thus not limited to Japan; it is seen elsewhere too.

Japan’s international reporting and elites

At the beginning of this article, we noted that elites influence Japan’s international coverage. Let’s dig deeper by looking at volume and content. First, we analyzed international news articles from the Asahi, Yomiuri, and Mainichi newspapers collected by GNV from 2015 to 2020. Using the identified “subject of the news” (※2) for each article, we examined how many international stories are told from an elite perspective. Here, we focus on political elites such as politicians and bureaucrats (※3).

The total number of international articles (※4) across all three newspapers in GNV’s database from 2015 to 2020 was 99,625. Of these, 56,677 were articles with elites as the subject. In other words, limited to international news, about 57% of all articles had elites as the subject. Next came 12,626 articles with “ordinary people” as the subject, and 5,784 articles with “the state and its affiliates/meetings (local level)” as the subject(※5). How should we think about the fact that more than half of international stories have political elites as the main subject? Let’s focus and consider three cases.

The climate crisis and elite-centered reporting

First, the climate crisis, mentioned at the outset. Here we examine the two years around the Paris Agreement, when measures against the climate crisis became a global task (January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2016). The Paris Agreement, adopted in December 2015, is a framework that requires all participating countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. How, then, was the climate crisis reported over these two years? There were 109 articles (98,602 characters) whose headlines contained “climate” or “global warming.” Of these, 73 articles (64,111 characters) had elites as the subject. That is about 67% by article count and about 65% by character count.

The climate crisis is a planetary problem. If coverage is skewed toward elites, we risk losing sight of the essence and the big picture. For example, there are people who are already being harmed or are expected to be harmed by the climate crisis. There are also aspects in which corporate greenhouse gas emissions and excessive consumption by people are linked to the crisis. Politics and economics involving elites are just one angle for understanding the climate crisis; the crisis can be considered from many angles, including the realities of victims, the actions of companies and consumers that cause the crisis, and concrete countermeasures we should take.

Ebola and elite-centered reporting

The second case is Ebola. While Ebola has occurred repeatedly in Africa, we examine the largest outbreak as of 2022, which began in Guinea in March 2014, spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone, and lasted two years. Including suspected cases, 28,616 cases were confirmed, with a fatality rate reaching 40%. Here we analyze the two years from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2016, which include the outbreak period. During this period, there were 47 international articles (26,605 characters) with “Ebola” in the headline. Among them, 25 articles (11,696 characters) were elite-centered—featuring announcements by local governments or the World Health Organization (WHO), or actions/measures by foreign governments providing support. That is about 53% by article count and about 44% by character count(※6).

A government official delivering a statement in front of the press (Photo: Mecklenburg County / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Of the 47 articles, eight (10,693 characters) were written mainly from a local perspective—that is, focusing on healthcare workers, patients, and their families. At about 17% by article count, this may seem small, but reports conveying local voices are often feature stories. As a result, the average length per article is greater, and locally focused pieces account for about 40% of the total characters on Ebola. The relatively high amount of local information in non-elite-centered pieces likely reflects that the situation with Ebola was unexpected, contained especially negative elements, was large in scale, and received sustained coverage.

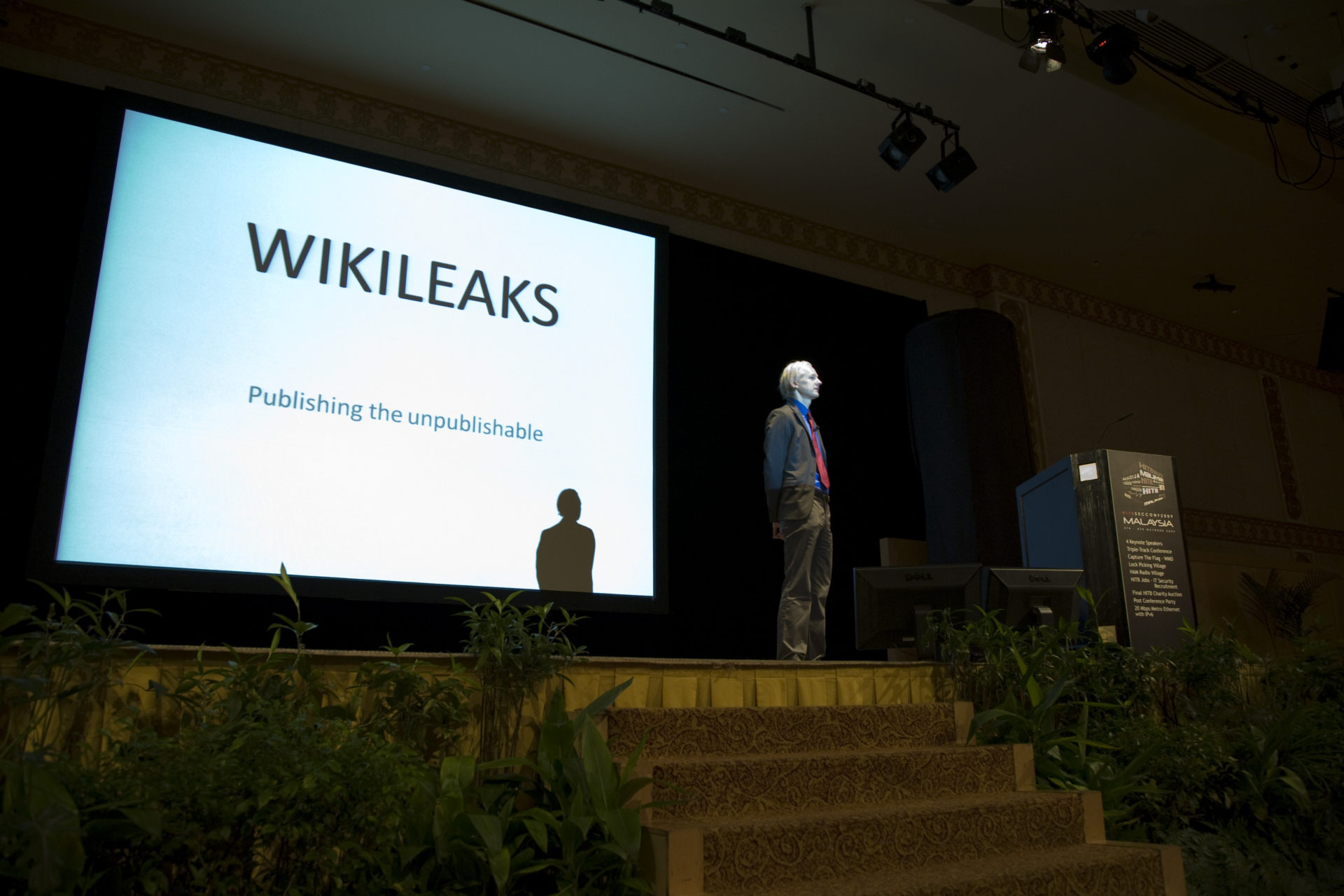

WikiLeaks and elite-centered reporting

The third case is WikiLeaks, an organization that publishes leaked confidential information. Well-known disclosures include video from 2010 showing a U.S. military helicopter killing civilians in Iraq, and emails damaging to the campaign of Hillary Clinton, a candidate in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The information WikiLeaks releases is mostly inconvenient for elites(※7). Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, was arrested in the UK in 2010 on a matter unrelated to WikiLeaks’ activities, and in 2012, while on bail, he sought asylum at the Ecuadorian embassy in London. In 2019, however, Ecuador allowed UK authorities to arrest him, and he is now detained in the UK. Proceedings to extradite him to the United States are underway.

Here, we focus on 2019, when Assange was arrested by UK police. From January 1 to December 31, 2019, there were 27 articles (14,236 characters) with “WikiLeaks” or “Assange” in the headline. Of these, eight (3,946 characters) were elite-centered(※8). Elite-centered pieces account for about 30% by article count and about 28% by character count.

Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks (Photo: Darryl biatch0 / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Compared with the first two cases, the share of elite-centered reporting here appears lower by both article and character counts. But the substance is not so simple. As noted, the information WikiLeaks releases tends to be inconvenient for elites. When elites have an incentive to conceal information that is unfavorable to them, holding those elites to account is precisely what journalism is for.

In practice, however, we found no pieces that took a skeptical view of elites. Only one short piece (325 characters) from the Yomiuri Shimbun—“Assange’s lawyers ‘will resist’ U.S. extradition”—primarily presented claims from Assange’s side. Even that article was brief and did not explain specific counterarguments to the positions of various countries. In other pieces where Assange was the subject (though not focused on his claims), only three articles (2,457 characters) explicitly stated his side. Most articles discussed the circumstances and reasons for his arrest, and the implications for politics and diplomacy, without addressing specific issues such as the opacity of the arrest process or the insufficiency of the charges. Viewed this way, even when Assange is the subject, most pieces are biased toward elite perspectives.

Causes and problems of elite-centered reporting

Why does reporting hew to elite perspectives? The first issue is that news organizations depend on elites as information sources. News outlets have a tendency to prioritize government press conferences and press releases. Through these, elites can disseminate information efficiently and reporters can receive it efficiently(※9). This leads to elite-generated information being reflected in coverage. News organizations may also regard elites as legitimate representatives of their countries.

There is also a journalistic method known as access journalism, in which journalists build relationships with elite sources to obtain leaks. In Japan, such a system with politicians is called the “ban-kisha” (press club beat reporter) system. Reliance on such sources can create risks that outlets will avoid publishing information unfavorable to those sources for fear of damaging the relationship. Furthermore, by relying on information supplied by elites, news organizations may stop gathering information themselves, and coverage may end up centered on elites.

Multiple cameras filming a press conference (Photo: Asian Development Bank / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The second issue is that the profession of journalism itself has become elite. Japan’s major media hire few people and require competitive exams, making entry difficult, and many hires come from top universities in general. In a 2018 Toyo Keizai ranking of hiring difficulty, the Nikkei, Asahi, and Yomiuri newspapers were all within the top 50 companies. In other words, many reporters graduate from the same level of universities as political elites. This is important not only for obtaining talented personnel but also for building networks useful for gathering information. It may also lead reporters to see issues from the same perspective as elites. For example, there is a theory that reporters write with an imagined readership in mind; if they imagine elite readers, they may prioritize information likely to interest elites.

Another factor that may make it harder for reporters to focus on non-elites is that they have less time to cultivate sources or canvass local residents. Press conferences, press releases, and deepening relationships with elites may be seen as more efficient uses of time and resources. This can create distance between the poor—removed from power—and journalists, leading to a structure in which poverty is underreported, or when it is covered, a gap emerges between reality and reporting.

So far we have looked at political elites and the media, but economic elites also have close ties to the media. A study of Western countries shows that corporate advertisers strongly influence the outlets through which they advertise. Japanese media also show a tendency to cover Japanese companies expanding overseas favorably. In the climate case discussed earlier, we saw articles about companies developing environmentally friendly technologies(※10) or providing financial support for tree planting in low-income countries(※11). Yet these pieces did not mention that those same companies had emitted large volumes of greenhouse gases and contributed to warming. Such stories can function as de facto advertising by improving a company’s image. This suggests a reciprocal structure between news organizations and their corporate sponsors. Another factor may be the possible reflection of nationalism in reporting, as outlets have incentives to run news that pleases domestic audiences.

Given these backgrounds, what problems does elite-centered reporting cause? First, it may make the media more susceptible to elite propaganda. There is a theory that elites, using their influence, interfere in coverage by shaping how specific information is emphasized, downplayed, or challenged, making it more likely that information favorable to elites will be conveyed in favorable ways.

Japanese and German leaders at a press conference (Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office, Cabinet Secretariat / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0])

Another problem is that it becomes difficult to learn about issues and phenomena that do not interest elites. As a result, people who are victimized may be ignored. In such a media environment, we may fail to recognize the severity of real situations and be unable to hold elites accountable, allowing problems to worsen.

For the watchdog to remain a watchdog

As we have seen, there is a close relationship between reporting and elites, which can lead to failing to notice, or not prioritizing, major societal problems. Elites influence coverage in many ways—as subjects of stories, as sources, and as suppliers of topics. This relationship includes structural elements and may not be easy to sever. What can be done?

One improvement is diversifying sources. Rather than waiting for government announcements, it would be desirable to make greater use of information held by local reporters to obtain information without going through governments. It may also be necessary to review journalist education in Japan. In the United States, journalists are generally expected to hold a bachelor’s degree in communications or journalism, studying reporting skills and ethics. In Japan, by contrast, it is common for news organizations to train reporters after hiring. Under such a system, there is a concern that new reporters, trained by senior reporters, are cultivated with a stance that leans toward power. There is a need to build environments that foster journalists equipped with reporting ethics. However, expecting news organizations to undertake these efforts is difficult because they have weak incentives to do so.

What else could be done? Some outlets convey perspectives different from those of elite media. Such media are called alternative media. For example, New Internationalist, a magazine launched by a humanitarian NGO, focuses on the world’s marginalized rather than elites. There are also efforts for those directly involved to speak for themselves. For instance, The Big Issue, a magazine sold by homeless vendors, reports from the perspective of the socially vulnerable. The International Network of Street Papers (INSP) provides a service that shares and distributes articles among street papers worldwide. Alternative media are expected to report with greater focus on the socially vulnerable.

A man selling The Big Issue (Photo: Sacha Fernandez / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In today’s internet age, even non-elite media can disseminate information effectively. Increasing reporting removed from elites and ensuring diversity in coverage would be one path to improvement. In any case, for journalism to be a mirror reflecting the truth and a watchdog monitoring power, it must first turn its gaze beyond elites.

※1 ① whether elites appear; ② whether celebrities appear; ③ whether it is about entertainment; ④ whether there is an element of surprise; ⑤ whether it is especially negative information; ⑥ whether it is especially positive information; ⑦ whether it is large in scale; ⑧ whether it is relevant to the audience; ⑨ whether it is a follow-up to previous news; ⑩ whether it aligns with the organization’s stance.

※2 ① State and its affiliates/meetings (central); ② State and its affiliates/meetings (local level); ③ Companies and their affiliates/meetings; ④ International organizations and their affiliates/meetings; ⑤ NGOs/NPOs and their affiliates/meetings; ⑥ Armed groups; ⑦ Religious organizations, their affiliates, and believers; ⑧ Ordinary people; ⑨ Wealthy; ⑩ Middle class; ⑪ Poor; ⑫ Researchers; ⑬ Animals; ⑭ Outer space; ⑮ Ethnic groups; ⑯ Refugees; ⑰ News organizations; ⑱ Healthcare workers; ⑲ Celebrities; ⑳ None (20 items).

※3 Here, when the subject is categorized as “State and its affiliates/meetings (central)” or “International organizations and their affiliates/meetings,” the article is considered elite-centered.

※4 International articles published in the Tokyo morning editions of the Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri newspapers from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2020.

※5 Other figures, corresponding to the numbering in ※2, were: ② 5,784; ③ 4,669; ⑤ 226; ⑥ 1,789; ⑦ 483; ⑨ 56; ⑩ 20; ⑪ 66; ⑫ 797; ⑬ 168; ⑭ 69; ⑮ 252; ⑯ 562; ⑰ 420; ⑱ 391; ⑲ 2,159; ⑳ 9,941. Note that because one article can have more than one subject, the sum does not match the total number of articles.

※6 Of the 25 elite-centered articles, five (2,789 characters) mentioned WHO’s slow initial response. While these can be seen as criticizing elites, all five were published after WHO acknowledged failures at a special meeting on Ebola on January 25, 2015, and thus do not negate the media’s dependency on elites by covering what elites themselves had made a topic.

※7 During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump praised WikiLeaks for releasing information unfavorable to Clinton.

※8 Of the eight elite-centered articles, one reported on a data leak in Ecuador and was not directly related to Assange’s arrest. However, because this survey used clear headline criteria, it is treated formally as an elite-centered international article like the other seven. Details are as follows: “Ecuador suffers nationwide data leak: account balances, personal IDs… 20 million people including Assange,” Asahi Shimbun, 2019/09/19.

※9 A press club is a voluntary organization of news outlets formed to request information disclosure from public institutions such as government ministries and parliaments and from industry groups. Member outlets are given privileged positions for newsgathering. While press clubs allow news organizations to efficiently report government announcements, they also foster dependence on government as a source.

※10 Asahi Shimbun, December 15, 2015: “Perspective: A society of net-zero emissions ushered in by new technologies—Paris Agreement adopted for climate action.”

※11 Asahi Shimbun, August 16, 2015: “Science Gate: Using forests to fight warming—The more forests are protected, the more developing countries benefit.”

Writer: Seita Morimoto

ここ数日の国内報道を見ても、大手メディアがエリート層に寄りすぎであることは明白だが、当記事で国際報道でもエリート層に極端に着目し、その他の世界・人々の声が届いていないことが良く分かる。日本にも海外同様、中立にジャーナリズムを学ぶ場を作る必要があるということには同意する。オルタナティブなメディアに注目してみる、という点は全く思いつかなかったので利用してみたい。

理想は、メディアが「番犬」の役割を果たすことですが、エリートや企業との結びつきにより、偏った報道がされている実態を理解しました。ウィキリークスなど、直接エリートから情報を入手しない方法も現れましたが、権力でねじ伏せられていると感じます。

私たち読者も、多様な媒体を使用し、エリートからの視点が多い報道を鵜呑みにしない努力が求められていると思いました。