Columns of tanks churning up sand along gravel roads, explosions in city streets, children whose tears have run dry. You have probably seen such scenes at least once in news reports on armed conflict. These images seem to vividly and constantly convey what is happening on the ground. However, how much do such visuals actually convey about the reality of a conflict? Reporting that relies on such imagery may lead us to think we understand the “tension,” “fierceness,” and “tragedy” of conflict. Yet it is likely difficult to grasp the full picture, including background factors and efforts toward peace. Here, while capturing the realities of conflict reporting, we consider steps toward better coverage.

Iraqi soldiers traveling by tank (Photo: United States Forces Iraq / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

War Journalism and Peace Journalism

To begin with, what do we mean by “war reporting” or “conflict reporting”? What easily comes to mind is coverage that focuses on scenes where force is used or where those in power issue statements. People who do such reporting are often called “war journalists” or “war photographers.” Conversely, we rarely see reporting that focuses on peaceful aspects. For example, you seldom hear terms like “peace reporting” or “peace journalist.” From this, it appears that when conflicts are reported, the focus is generally placed more on events related to the use of force than on peace.

This tendency may be characteristic of conflict reporting. Let us compare it with coverage of infectious diseases—another serious issue facing the world today. Here we consider reporting on COVID-19, which has appeared in the news almost daily since around 2020. Of course, COVID-19 coverage includes negative topics such as daily case counts, death rates, and strained medical systems, but it also frequently focuses on how to address or resolve the pandemic—such as therapeutics, vaccines, and ways to prevent infection and severe illness. Such reporting consistently aims at “health,” and you rarely find coverage that only dwells on “ill-health.”

In this way, it seems that the way the media treats diseases that threaten health differs greatly from how it treats conflicts that threaten peace. Researchers who are critical of current trends in conflict reporting argue that coverage of conflict can be divided into two approaches: war journalism and peace journalism. Let us look at each in turn.

First, we will outline the characteristics of war journalism, which could be described as the conventional approach to conflict reporting. War journalism is easy to understand if you think of sports commentary. In sports commentary, the focus is on the back-and-forth between two clearly divided teams. During the match, commentators relate what is happening in the moment while keeping their eye on who will win. The basic structure is the same in conflict reporting considered to be war journalism. Here too, the conflicting parties (teams) are clearly split into two, and the axis of confrontation is emphasized. Even though, in reality, other countries, organizations, and stakeholders that do not fit this simple structure may influence the conflict, reporting centers on a binary opposition. In some cases, a particular party to the conflict is portrayed as the “villain.” Especially when the reporter’s own country is involved, there is a notable tendency to begin by casting the “other side” as “evil.” Some say the media may even turn a blind eye to their own country’s unreasonable actions, lies, or cover-ups, while highlighting only the problematic actions of the other side.

In addition, war journalism amplifies some “voices” while muting others. In other words, as sources or featured actors, the “voices” of elite participants—leaders, ministers, military officers of parties engaged in the fighting—are reported more frequently. By contrast, the “voices” of ordinary citizens and of people and organizations seeking peace are rarely reported. Even when ordinary citizens are featured, coverage often focuses on quantifiable aspects such as casualties and displaced people. Meanwhile, less visible realities—psychological trauma, impacts on social structures such as increases in poverty—are less likely to be reported.

Conference on Women, Peace, and Security (Photo: UN Women / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Peace journalism emerged as a critique of such realities in conflict reporting. During the Gulf War in 1991, long-time peace studies scholar Johan Galtung proposed that conventional conflict reporting hampers understanding of conflicts and even fuels them. Peace journalism seeks to report on conflicts in the way health reporting does, as described above. Its features include focusing on the background and causes of conflicts, highlighting the voices and perspectives of all stakeholders, and covering peaceful possibilities and initiatives. Even if there are unreasonable actions, lies, or cover-ups by the “home country” of the media outlet, peace journalism aims to expose and bring them into the light. By comprehensively and objectively capturing various aspects of conflict and providing perspectives and information oriented toward peace, peace journalism has the potential to contribute to conflict resolution.

So far, we have discussed viewing conflict reporting through two lenses: war journalism and peace journalism. In practice, however, actual reporting often contains elements of both. Therefore, to understand the realities of conflict reporting more objectively, we need to examine in detail which elements—war journalism or peace journalism—are emphasized or reported more frequently.

Trends in Conflict Reporting Seen in NHK News Watch 9

Various research institutions have conducted studies on war and peace journalism targeting the media in many countries. The concept is also used in practice, with trainings and courses for journalists conducted in many countries. However, studies targeting Japanese media are not often seen. So, how does Japanese media cover conflicts? Is it closer to war journalism, or does it show tendencies of peace journalism?

This time, we decided to analyze a television news program as a case study. Specifically, we examined NHK’s “News Watch 9” over the three months from October 1, 2021 to December 31, 2021. After watching all broadcasts during the period, we extracted items that could be considered conflict reporting—reports on conflicts, frictions, and confrontations. We found 18 such items, totaling approximately 60 minutes of airtime. Among these 18 items, those involving the use of force included coverage of the coups in Myanmar and Sudan and the movements opposing them, a terrorist attack in Afghanistan, and armed clashes in Yemen. Items involving friction and confrontation without direct armed conflict included the growing tensions between Russia and Ukraine, North Korea’s missile development and launches, and China’s advances into areas claimed as the territory of Taiwan and Japan.

For the analysis, we used a point-based method to evaluate whether each item leaned more toward war journalism or peace journalism. As criteria for assigning points, we used eight features (※2) from a previous study (※1) shown below.

For each item, we added 1 point when a feature above applied (※3) and then examined which approach the report contained more of. We summarized the date, duration, content, and which type the report leaned toward for the 18 items in the two tables on the following pages. In the bar graphs displayed to the right of each entry, yellow indicates the proportion of war journalism features observed, and blue indicates the proportion of peace journalism features observed.

From our analysis, several characteristics of conflict reporting in Japanese media emerged. First, of the 18 items analyzed, 17 leaned more toward war journalism. On average, the points assigned to each item were about 4.1 for war journalism and about 1.8 for peace journalism—more than twice as many for war journalism. From this, we can say that conflict reporting during the entire study period strongly exhibited war journalism tendencies.

Second, we found that war journalism tendencies were particularly strong when Japan was a party to the conflict or closely related to it. Among the analyzed items, coverage of North Korea’s missiles, China’s moves into seas near Japan, and Russia’s military activities can be considered conflicts in which Japan is a party or which have relatively large impact on Japan. Regarding Russia, we categorized it as having significant impact on Japan because the core country of the NATO force opposing Russia is the United States, Japan’s ally, and because Russia conducted military exercises in waters near Japan. In these 9 items, the average points were about 5.2 for war journalism and about 2 for peace journalism. For the remaining conflict items, the averages were about 3 for war journalism and about 1.7 for peace journalism—similar in that war journalism scored higher, but with a smaller gap than when Japan was a party or closely aligned. One possible reason for this tendency is that when Japan could be a party to a conflict, the media may be intentionally seeking to convey a sense of urgency.

Below, we look in turn at four of the conflict reports analyzed: coverage of Russia’s moves regarding Ukraine, coverage of North Korea’s missiles, coverage of the conflict in Sudan, and coverage of armed clashes in Yemen.

Case 1: Russian moves regarding Ukraine

First, we look at approximately 10 minutes of coverage aired on December 24, 2021, following Russia’s concentration of troops near the border with Ukraine. In recent years, against the backdrop of intensifying competition for spheres of influence between NATO and Russia in Ukraine, attention has focused on the latest moves by Russia and Western countries.

Let us summarize the flow of this report. It begins by stating the event at hand: Russia has amassed troops near the border with Ukraine. It then introduces the historical background since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, during which Eastern European countries became arenas where the intentions of Russia and NATO collided. From there, the report proceeds mainly in the form of an interview with a Russian international relations scholar about Russia’s security strategy. It concludes by noting that developments in Russia are having an impact on Japan and touches on prospects going forward.

Russian soldiers deployed to the Crimean Peninsula — broadcast on December 24, 2021

War journalism features were evident in this coverage. First, the footage used creates a sense of tension, as if Russia were heading inexorably toward war. In the first half, although no actual military clashes had occurred, the report shows “training footage released by the Russian Ministry of Defense,” including tanks firing shells while moving, and scenes from Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia. In the second half, while referencing Russia’s past interventions in Georgia and Ukraine, it uses shelling scenes of unknown provenance. These serve to impress on viewers that Russia is a country inclined to use force and to add tension to the report.

Beyond visuals, the narration and comments by the anchor also reveal the program’s stance. The narration describes Russia’s moves toward Ukraine as “baring its fangs,” a phrase suggesting Russia is about to harm Ukraine. In an interview with a Russian scholar, the anchor asks questions like, “Will your country invade Ukraine?” and “Why did the Russian and Chinese navies join together to threaten Japan?”—framing Russia as the “villain.”

Furthermore, there is little reporting on the NATO forces that could be seen as encircling Russia in Eastern Europe or on the actions of the United States in Ukraine, nor are their intentions scrutinized. The report makes it appear as if Russia is irreversibly heading toward war and does not mention possibilities for peaceful resolution. Even so, points for peace journalism were assigned to some extent because it explained, to a degree, the background leading to the current developments, such as relations with NATO since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Case 2: North Korea’s missiles

Next, we look at coverage of North Korea’s missiles. We analyzed 6 items (※4) totaling 10 minutes related to the development and launch of North Korea’s missiles. Despite a ban by the United Nations, North Korea has repeatedly developed and tested ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons and has been subject to strict sanctions. The six items analyzed mainly reported, in sequence with new events and information, that North Korea is advancing its missile development and improving performance; that missiles were actually launched and their characteristics; and the reactions of the United States and South Korea.

North Korea’s missile launch — broadcast on October 20, 2021

A common feature across these items is the thorough effort to impress on viewers that North Korea is a nuclear-armed threat. By interviewing experts to substantiate improvements in missile performance, repeatedly airing launch footage, and reporting items as “breaking news,” the reports appear aimed at making viewers perceive the threat as immediate. Notably, in the item aired on October 21, 2021, footage of Kim Jong-un striding past a missile accompanied by senior officials, alongside shots of him observing a military parade from a high vantage point, emphasizes his power within North Korea and seems to imply that Kim alone is to blame for the nuclear and missile issue. Of the roughly 10 minutes of coverage, more than 4 minutes consisted of missile footage and photos. As with the Russia case, the coverage overwhelmingly focused on elements related to the use of force, portraying North Korea—and Kim Jong-un—as a fear-inducing “villain.” There was little reporting on solutions or diplomatic elements; the content focused single-mindedly on conveying a sense of urgency. Some items did mention moves at the UN Security Council or that the United States, South Korea, and Japan were considering new coordinated responses, but overall the features of war journalism were pronounced.

Case 3: Conflict in Sudan

Third, we examine roughly 2 minutes of coverage aired on October 25 and 26, 2021 about the conflict in Sudan. In 2019, Sudan’s long-standing authoritarian regime collapsed, and a transition to civilian rule began. However, in October 2021 the military staged a coup and detained the prime minister. The prime minister temporarily returned to office in November, and there were signs of democratization. Even so, pro-democracy groups called for demonstrations demanding genuine democratization. Clashes between pro-democracy forces and the military continued into 2022. The two reports analyzed showed the military declaring a state of emergency in response to demonstrations and aired footage of the protests while reporting casualty numbers and the actions of pro-democracy forces.

Statement by Sudan’s military — broadcast on October 26, 2021

In these two items, much of the airtime consisted of footage of the protests, seemingly conveying the on-the-ground situation in detail. The images of people clashing with the military amid smoke and flames indeed convey the chaos. As sources, statements by pro-democracy forces and the local medical association were cited in part, showing multiple actors. However, within roughly one minute per item, there was little reporting on the background of the coup and the demonstrations or on moves toward peace. While viewers are likely to be left with an impression of clashes, this coverage alone makes it difficult to adequately consider or understand Sudan’s current problems, their causes, and potential solutions.

Case 4: Armed clashes in Yemen

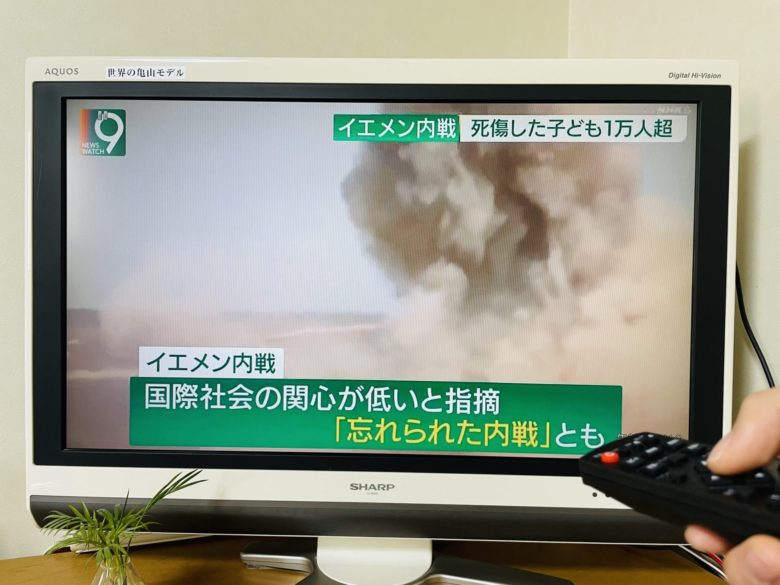

Finally, we consider approximately one minute of coverage on October 20, 2021 about the conflict in Yemen. In Yemen, after the “Arab Spring” led to internal strife within the regime, the involvement of neighboring countries and various factions entangled diverse interests, resulting in a complex armed conflict ongoing since 2014. By the end of 2021, the death toll was estimated at 377,000, and the conflict has been described as “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.”

Scenes of armed clashes in Yemen — broadcast on October 20, 2021

The report referred to this conflict as a “forgotten civil war” and discussed the need for attention and support from the international community. In terms of the volume of coverage by Japanese media, it could indeed be said to have been “forgotten” by Japanese outlets as well. However, given that multiple foreign militaries are involved, calling the conflict a “civil war” may itself hinder understanding of the situation. In this sense, the information provided by this report could foster misunderstandings about the conflict in Yemen. Moreover, it did not touch at all on the background of the conflict or on moves toward peace. As with the Sudan coverage above, the extremely short airtime makes it difficult for viewers to gain an understanding of these armed clashes.

Toward better conflict reporting?

We have examined Japanese media coverage of conflicts through the lenses of war journalism—which emphasizes violence and confrontation—and peace journalism—which focuses on root causes and moves toward peace. There are, however, critical views of peace journalism as well. The criticism is that in focusing on peace, it loses objectivity as journalism. That is, journalism should observe events and report them as they are, but in trying to promote peace, it becomes a party to the event. By doing so, peace journalism becomes less journalism and more advocacy for peace.

Yet, as discussed above, conventional war journalism has significant problems too. As a new approach to conflict reporting, journalist and researcher Ross Howard and others have proposed Conflict Sensitive Journalism (conflict sensitive journalism, hereafter CSJ) over the years. CSJ means not merely relaying facts related to conflict events, but that reporters strive to understand the causes of a conflict and actively seek out more perspectives and more voices. In doing so, they aim to capture and convey as comprehensively as possible everything from causes to moves toward peace. While CSJ overlaps in many ways with peace journalism, a crucial difference is that CSJ does not aim to promote or contribute to peace, nor does it campaign for it. Capturing events more accurately and comprehensively may in the end lead to resolution and prevention of recurrence, but that is not its goal.

Journalists attending Yemen peace talks (Photo: UN Geneva / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

We have seen that conventional war journalism, by concentrating on one aspect of conflict, can hinder understanding and make possibilities for peaceful resolution harder to see. Our analysis found such tendencies, which likely apply broadly to conflict reporting in Japan. At the same time, we introduced peace journalism, which focuses on causes and peace, and the newer CSJ approach, which seeks to contribute to public understanding by reporting on conflicts more comprehensively and objectively. What is conflict reporting for? Media outlets and journalists should reaffirm the significance of communicating about conflicts and conduct their reporting accordingly.

※1 A 2019 study examining how Malaysian newspapers reported on the South China Sea issue. In this work, eight items characterizing war and peace journalism, based on Johan Galtung’s arguments, are presented.

※2 The eight features: eight paired items characterizing war journalism and peace journalism as proposed by Johan Galtung.

Elite-oriented vs. people-oriented: Are sources and actors mainly government and military officials, or are ordinary people also featured?

Differentiation-oriented vs. agreement-oriented: Does coverage focus mainly on differences in positions, issues, and frictions? Or does it focus on events where parties might reach agreement?

Here-and-now vs. causal: Does it report only what happened, or does it also cover background and long-term consequences?

Demonizing the other vs. shared responsibility: Does it presume the opposing side is the “villain”?

Two-party structure vs. multi-party structure: Does it oversimplify the conflict as merely bilateral, or does it consider the existence of multiple, diverse actors?

One-sided vs. neutral: Does it take sides or introduce bias in its reporting?

Win-lose vs. win-win: Is the outcome framed solely in terms of one side’s victory or defeat, or are alternative solutions mentioned?

Subjective language vs. objective language: Are negative or exaggerated terms used for the “villain,” or is neutral, objective language used?

※3 When both features within the same item were observed, we tallied the breakdown of airtime and allocated the single point proportionally. Thus, fractional values occurred in some cases.

※4 Aired on October 1, October 6, October 12, October 19, October 20, and December 2, 2021.

Writer: Yosuke Asada

Graphics: Yosuke Asada

限られた時間、文字数で視聴者にインパクトのあるメッセージを残すために、テレビ、新聞は、ともすれば紛争の極一部を切り取り、実際とは逆のような印象を与えることもあるかも知れない。ピースジャーナリズムよりウォージャーナリズムの方が、より多くの人の目を引くのは確かだろう。そんな中、北朝鮮の紛争などは例外だが、私の思った以上に日本のピースジャーナリズムも頑張っているな、と言う印象だった。

浅田氏はここからさらに踏み込み、より客観的なコンフリクト、センシティブ、ジャーナリズムを紹介している。

我々日本人も、対岸の火事だとは思わずに、一人一人が民族問題に積極的にかかわること、またメディアはそのような人に対して客観的な情報を提供することが求められる。

ストーリーで気になったから見にきました。

浅田の記事?を読むことによって、確実に自分の視野が広がりました。

今回紹介されていた紛争報道に限らず、ニュースを見るだけで全てを知った気にならず、ニュースを切り口にし、世の中で起きている事柄に注目して、偏りのない情報を得る必要があるのかなと感じました。

こういった固い文章を読むことが少なくなってしまったので、久しぶりに読んで面白かったです。ありがとう。

次の記事も楽しみにしています。

ストーリーで広報してね〜

ウォー・ジャーナリズムとピース・ジャーナリズムという考え方を初めて知りました。日本は報道に関してもアメリカの追随、とはよく言われることですがこの問題でも非常に偏りが多く、安易に敵・味方を作り出し分かりやすい構造に落とし込もうとしていることが気になっていました。もう少しその問題が起きた背景や関係する国々(2国間あるいは3国のみはありえないので)についても伝えるような報道が増えてこないと物事の本質を理解するのに役に立たないですよね。興味深い記事をありがとうございました。