Emails, chats, call histories, notes, contacts—every kind of information on your smartphone can end up in someone else’s hands without you knowing, while your camera and microphone are switched on / off remotely and you are constantly being watched. In July 2021, it was revealed that “Pegasus,” spyware (※1) capable of enabling such a terrifying situation, had infiltrated devices belonging to politicians, activists, and journalists in various countries. There have been cases in which journalists were killed or arrested after being targeted by Pegasus, making it a major threat to journalists who handle confidential information.

At the same time, the incident can also be viewed differently. While some of Pegasus’s targets were journalists, it was also journalists who exposed the problems surrounding Pegasus. Journalists and news organizations worked together to investigate and have continued to report new findings after the revelations.

Throughout history up to the present day, there has been friction between states that try to conceal wrongdoing or inconvenient truths and the journalists who seek to expose them. In today’s world of advancing technologies, press freedom can be under threat even in countries where it is supposed to be guaranteed. How are journalists and news organizations—often described as “watchdogs” of power—confronting state authority? And how are states responding to them? This article focuses particularly on how technological progress is affecting journalism, mainly through examples from countries generally considered to guarantee press freedom, and also looks at related reporting in Japan.

Journalist reporting with a smartphone (Photo: Tony Webster / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

Leaks and Journalists

Leaks are crucial when journalists—sometimes called the “watchdogs” of power—seek to expose wrongdoing by those in power. Confidential information that includes wrongdoing is usually restricted to a limited group of people for viewing and management, leaving journalists and the public with little to no access. However, once information is provided by an insider, journalists can analyze it and conduct investigative reporting (※2), broadcasting wrongdoing around the world. Before the spread of information technologies such as the internet, sources had to physically remove documents—on paper, for example—to leak them, but today it is possible to exchange information as data.

Most people who leak information do not want their identities revealed, as they risk facing severe punishment. For example, Edward Snowden, who exposed internet and telephone surveillance and hacking conducted by entities such as the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and the U.K. Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), was charged with multiple counts including espionage in 2013 and sought asylum in Russia. Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning, a former U.S. Army intelligence analyst who leaked classified U.S. military information about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, was convicted in 2013 on 20 counts including information leaks and was subjected to inhumane treatment in detention facilities. If whistleblowers must pay such a heavy price in exchange for exposing wrongdoing, they may be too afraid to leak information, leading to fewer leaks. When leaks decrease, journalists and the public lose one means of learning the truth.

As the prosecution of leakers indicates, leaks and reporting based on them are accompanied by ethical and legal issues and are not universally supported. Leaks can include information supplied by insiders with access to internal documents as well as material obtained illegally through hacking. Some publishers even welcome submissions from hackers, but hacking is considered a crime in many countries, and opinions are divided over publishing information obtained illegally by hackers. Including whistleblowing, from ethical and legal perspectives leaks cannot be called categorically “right,” but many instances of “illegal” acts have exposed wrongdoing and corruption that run counter to the public interest. If the public interest in disclosure is high, using information obtained by unlawful means as the basis for reporting has become a common tendency in journalism worldwide.

Even though the development of information technology and the spread of electronic devices have made leaking easier, methods like email attachments can make it easy to identify the leaker. As a result, systems designed to protect the anonymity of leakers have been developed. A representative example is WikiLeaks. WikiLeaks is a non-profit organization established in 2006 that develops and operates a whistleblowing platform. Based on the belief that government and corporate transparency prevents abuses of power, it has published information mainly obtained through whistleblowing. What made WikiLeaks groundbreaking was its rigorous protection of sources’ anonymity. It implemented a proprietary encryption system so strict that even WikiLeaks itself could not identify its sources. To date, WikiLeaks has released more than 10 million documents and analyses, including the Afghan War (75,000 documents), the Iraq War (400,000 documents), U.S. diplomatic cables (250,000 documents), and a draft of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement. These revelations, including a video that brought WikiLeaks global fame showing a U.S. military helicopter firing on civilians in Iraq, exposed various wrongdoings and injustices. While WikiLeaks has at times collaborated with news organizations, it has primarily published information directly on its website.

Online security training bringing together hackers and journalists (Photo: Ophelia Noor / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The non-profit organization DDoSecrets (Distributed Denial of Secrets), founded in 2018, also uses the system known as “Tor,” which enables data to be transmitted anonymously, to publish information it receives. As an organization, it does not conduct exhaustive investigations or present conclusions on the published materials; rather, it aims to function as part of the broader journalistic ecosystem by providing them to journalists and citizens who need them.

News organizations have also begun building mechanisms that allow sources to leak information safely. SecureDrop, a system introduced by over 50 news outlets worldwide, including the New York Times and the Guardian, allows newsrooms to receive information from anonymous sources securely and is free to use. With technological progress, leaking is becoming more anonymous and safer for leakers, conducted electronically with careful consideration for their security.

Cross-border collaboration among journalists

To protect press freedom and strengthen capabilities in gathering, analyzing, and disseminating information in order to produce higher-quality investigative reporting, journalists around the world are leveraging advanced communication technologies to collaborate. As mentioned earlier, WikiLeaks and Snowden worked with various news organizations to tell the truth. Sometimes such collaboration is organized. A representative consortium for investigative reporting is the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The ICIJ network includes 267 journalists in 100 countries and territories and collaborates with over 100 media outlets. The leak of the Panama Papers is well known, but beyond that the ICIJ has conducted investigative reporting on secret dealings and tax avoidance/evasion by global elites and corporations through tax havens, including China Leaks, Luxembourg Leaks, and the Paradise Papers. It has also exposed corruption and wrongdoing involving politicians and major corporations worldwide, such as the West Africa Leaks and Luanda Leaks.

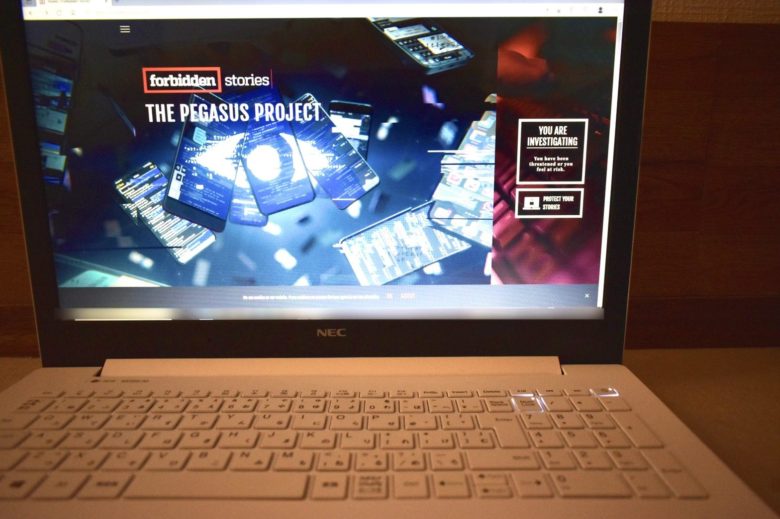

The spyware “Pegasus” mentioned at the outset is also being investigated in depth by the “Pegasus Project,” a collaboration between the international human rights NGO Amnesty International and “Forbidden Stories,” a network comprising 17 news organizations and more than 80 journalists from around the world. Forbidden Stories is a journalist network that continues and publishes investigations when journalists face threats, killings, or arrests that make it impossible for them to carry on their work. Collaboration among journalists can improve the efficiency and quality of investigations. Moreover, even if one journalist involved in an investigation is silenced, others can take over and ensure the information reaches the public. Such solidarity among journalists demonstrates a determination not to bow to power and to pursue the facts.

The Forbidden Stories website (Photo: Yumi Ariyoshi)

Leaks being hindered

While journalists use various technologies to uncover the truth, states are moving to obstruct their work. In particular, leaks of state secrets are defined as illegal in many countries, as noted earlier. In the United States, the Espionage Act—enacted during World War I to prevent leaking information that could harm the military—had rarely been applied. However, under the Obama administration, it began to be applied even to those who leaked in the public interest. For example, former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer John Kiriakou was arrested in 2013 on charges including violating the Espionage Act after discussing illegal interrogation methods, such as waterboarding, on U.S. television. The line between leaking or spying that threatens national security and whistleblowing that seeks to expose wrongdoing can be blurry, but even if a leak reveals wrongdoing in the public interest, there is still a risk of arrest under the Espionage Act.

Prosecution of those who receive and publish leaks is also a major problem. In 2019, Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, was indicted by the United States on 18 counts under the Espionage Act and other statutes in connection with the leaks by Manning mentioned earlier. The charges include conspiracy, aiding and abetting, and incitement involving Manning, and even apply the Espionage Act to the mere act of publishing leaked information. Seeking more information from a source, trying to protect that source’s identity, and especially publishing the information received are routine duties for journalists and news organizations, not limited to Assange. If Assange is convicted, it could set a precedent that treats the “routine” work of journalists as “illegal,” which is a serious concern.

A rally calling for Assange’s release and opposing his extradition to the United States (Photo: Garry Knight / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

After a separate arrest warrant was issued for Assange in Sweden, he feared extradition to the United States, applied for asylum to Ecuador, and was sheltered in the Ecuadorian Embassy in the U.K. for seven years. Relations with the Ecuadorian government deteriorated, partly due to a change in president, and he was arrested by British police at the embassy in 2019. As of September 2021, he is being held in a U.K. prison, and the United States is seeking his extradition. The British court has so far avoided a political decision and has denied extradition on the grounds that he might commit suicide if sent to the U.S., but the U.S. has appealed. If Assange is convicted and punished, it could create a precedent that “simply publishing leaks is a crime,” an event that poses a significant threat to press freedom.

Obstruction targeting journalists who publish leaked information is not limited to the United States. In Australia, after the public broadcaster obtained and published government documents alleging that Australian special forces killed unarmed civilians in Afghanistan, police raided the broadcaster’s headquarters in 2019. The warrant sought reporters’ notes, emails, and even passwords, apparently to identify the source of the documents. In South Africa, a law was passed in 2011 that could punish journalists and editors who receive government materials deemed classified. Japan similarly enacted the Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets in 2013, with penalties for leaking, illegally obtaining, conspiring to obtain, abetting, or inciting the disclosure of information designated as “Specially Designated Secrets” into law. In other words, not only those who leak but also the journalists who receive the information could be prosecuted under this law. From the time it was proposed, there were many objections that the law could be applied arbitrarily by the administration and undermine press freedom and the freedom to gather news. Under the U.K.’s Official Secrets Act, it is also a crime for government personnel to disclose classified information and for journalists to publish it as well. More recently, amid concerns that new technologies are enabling leaks, there have been moves to expand the scope and strengthen penalties under the Official Secrets Act, which has not been updated since 1989, prompting strong opposition from media organizations.

Australia’s public broadcaster reporting in Afghanistan (Photo: NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Online reporting being obstructed

Advances and the spread of communication technologies have expanded the arena for news dissemination from broadcast and print to the internet. However, state monitoring and restrictions over online spaces have also intensified. In China, where information control—including of the press—has long been strict and press freedom is scarce, the spread of the internet initially seemed to offer a chance to connect with the outside world. In reality, large-scale online censorship and blocking of access occur routinely, making it difficult for journalists to publish critical reporting about the government or for citizens to research it. In addition, interviews and press conferences conducted via SNS and other online channels were banned in 2014. Besides the authorities that oversee internet monitoring and regulation, companies operating internet services are required to self-censor, employing large numbers of people to delete content deemed “harmful” to the regime—a labor-intensive tactic. The latest technologies are also used to detect “harmful” keywords and block access. Moreover, journalists are frequently detained not only for direct criticism of the government but also for exposing the corruption of local politicians via SNS, creating an environment in which reporting of all kinds is difficult online.

In the Philippines, an anti-terror law enacted in 2020 allows authorities, based on a vague and broad definition of “terrorism,” to detain individuals for up to 24 days without a warrant if they commit acts that “endanger public safety.” The law also applies to online expression, creating the possibility of arrest for critical statements or reporting about the government. In addition, “cyber libel” charges have been applied to news sites and journalists who report critically on the government in various cases. In one case, the law was applied because a spelling was corrected in an article originally posted before the law was passed, highlighting the problem of the state’s arbitrary use of laws.

Maria Ressa, a journalist arrested in the Philippines for cyber libel (Photo: Deutsche Welle / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The challenges to press freedom have intensified further due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to restrictions on movement in various countries that have made reporting more difficult, there are concerns that journalists’ confidentiality could be compromised by government use of cellphone location data for contact tracing and other measures. Some countries have also passed laws under the pretext of punishing “false” information during the chaos of the pandemic, effectively suppressing press freedom. In 2020, there were moves in multiple countries—such as Brazil, Malaysia, and Hungary—to address “fake news.” However, these measures often create laws such as “anti-fake news acts” with unclear targets, enabling governments to arbitrarily punish critical voices online, or block access to sites that disseminate information inconvenient to the government under the banner of combating “fake news,” raising concerns about the suppression of press freedom.

Examples of technology-based attacks on journalists

Governments seeking to prevent the exposure of inconvenient truths do not rely solely on laws or search and seizure—they also use advanced technologies. The spyware “Pegasus,” mentioned at the beginning, was developed by the Israeli cyber company NSO Group. Ostensibly intended to support investigations into crime and terrorism, it is sold only to governments approved by Israel’s Ministry of Defense. In 2021, Amnesty International obtained and leaked a list of up to 50,000 phone numbers believed to be potential Pegasus targets. The list included numbers belonging to politicians, human rights activists, and journalists. While NSO Group denies the allegations and says the list has no special significance, it is believed to reflect numbers of interest to NSO’s clients. Ten countries—including Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Hungary, India, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Morocco, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—are considered major customers, many of which are known for strict information control and serious human rights violations to maintain authoritarian rule. Pegasus can infect devices without any action by the user—such as clicking on a link in an email—and once infected, it can access virtually all information and functions on a device like a smartphone. However, it is difficult for device owners to detect infection or for investigators to confirm such access, and a full picture has yet to emerge.

NSO Group website (Photo: Yumi Ariyoshi)

In some cases, journalists targeted by this spyware have faced imminent threats to their lives. For instance, in the case of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who was murdered after criticizing his government, it was later found that his fiancée’s phone had been targeted by spyware. Moroccan journalist Omar Radi was reportedly placed under surveillance after being arrested by authorities, having been attacked by Pegasus. In Mexico, freelance journalist Cecilio Pineda Birto was murdered after reporting that criticized state police and politicians, and his phone was also selected as a Pegasus target. While it is unclear whether information was actually extracted via Pegasus, the technology could in principle reveal a target’s location. Journalists in many other countries have been targeted as well, and in India alone, more than 30 journalists were reportedly on the list.

Pegasus is far from the only spyware that threatens journalists. As technology advances, spyware is becoming more complex and cheaper, making it more accessible as a surveillance tool for governments to monitor journalists and citizens. We may have to assume that journalists’ phones worldwide are constantly at risk of surveillance—and that journalists themselves are at risk.

Do Japanese media grasp the gravity of the matter?

Regarding Pegasus, a major threat to journalists around the world, the three major Japanese dailies (Yomiuri Shimbun, Asahi Shimbun, and Mainichi Shimbun) each ran an initial story based on U.S. newspaper reports and only 3 or 4 follow-up pieces (※3). The issues surrounding Pegasus are complex, and independent reporting is difficult because investigations require technical knowledge and extensive reporting networks. However, it is worth examining why they missed the steady stream of follow-ups published by media in other countries, including U.S. outlets.

(Photo: fas / Pixabay [Pixabay License])

As for Assange, whose case involves prosecuting a journalist for receiving and publishing leaks and represents a crucial point for the future of journalism and the protection of press freedom, the response from the three major dailies was limited (※4). The Asahi Shimbun alone expressed concern in an editorial titled “Worrying Pressure on the Right to Know,” stating that speech suppression in the name of national security, as in Assange’s case, is “not someone else’s problem,” highlighting the issue. However, the three other articles in Asahi related to the application of the Espionage Act to Assange and two articles in Mainichi were limited to reporting the fact that he was indicted under the Espionage Act or to detached phrasing such as, “There are concerns that classifying the disclosure of confidential information as a violation could affect the activities of news organizations.” Yomiuri had no reporting related to the Espionage Act. Nor were there articles expressing concern about press freedom regarding the U.K. court proceedings on his extradition to the U.S. Assange’s indictment is by no means someone else’s problem for Japanese media. If a precedent is set in the United States—where Japanese media have close ties—that “publishing leaks is a crime,” journalists and news organizations in Japan could face prosecution under similar reasoning. Japanese media should closely watch this case, which could greatly shake press freedom worldwide depending on how it is handled.

It should also be noted that Japanese media outlets are not necessarily safe for would-be whistleblowers. Most newspapers, magazines, and TV stations solicit information on their websites, and while they include statements like “We will always protect our sources,” it is unclear what measures they have in place against hacking or government demands for disclosure. Not a single Japanese news organization has adopted SecureDrop or similar high-security, highly anonymous leak systems, suggesting a low awareness of source protection.

Journalists conducting an interview (Photo: Piqsels [CC 0])

Summary: Tomorrow, it could be us

As we have seen, technological progress works for and against journalism. On one hand, the internet and improved communications help journalists gather information, support their role as watchdogs of power, and expand their channels of dissemination. On the other hand, technology threatens journalists and obstructs their work. While journalists leverage technology to further expose wrongdoing, even countries that proclaim press freedom see those in power using cutting-edge technologies and laws to hinder journalists’ efforts.

Even when the secrets of the powerful violate the public interest, are the journalists who expose them invading privacy or threatening national security as “spies”? As technology continues to advance, protecting press freedom while using the latest technologies will be vital to curbing abuses of power that run counter to the public interest and building a society that does not tolerate wrongdoing. To that end, news organizations and citizens around the world must share a firm stance against the increasingly oppressive attitudes toward the media and journalists seen in many countries in recent years. We must adopt a global perspective and treat violations of press freedom abroad as if “tomorrow, it could be us.”

※1 Spyware is software that sends information from electronic devices such as computers and smartphones to the internet. In many cases, users continue to use their devices without realizing such software is installed, and information is transmitted externally without their knowledge.

※2 Investigative reporting is a method by which news organizations and journalists independently uncover issues through their own investigations and report on them under their own responsibility.

※3 Counted using the print-archive search systems of the Yomiuri Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Asahi Shimbun (Yomiuri Shimbun Yomidas Rekishikan, Mainichi Shimbun MaiSaku, Asahi Shimbun Kikuzo II Visual). Here, without limiting publication period or format (region), each instance that mentioned Pegasus, the spyware, in the headline or text was counted as one item. The result was 4 items for Yomiuri and Asahi, and 6 items for Mainichi. (Accessed September 2, 2021 )

※4 Reviewed using the print-archive search systems of the Yomiuri Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Asahi Shimbun (Yomiuri Shimbun Yomidas Rekishikan, Mainichi Shimbun MaiSaku, Asahi Shimbun Kikuzo II Visual). Here, without limiting publication period or format (region), the contents of the headlines or text were confirmed. The result was 2 items in Yomiuri (which did not directly mention the “Espionage Act,” instead describing “obtaining and leaking documents related to national defense”), 4 items in Asahi, and 2 items in Mainichi regarding the application of the Espionage Act to Assange. (Accessed September 2, 2021)

Writer: Yumi Ariyoshi

日常的に「報道の自由」ついて心配することはありませんでした。でもこの記事を読んで、自由は保障されているわけではないと感じさせられました。民主政(民主主義?)に影響することなので、1人1人関心を持つべき話題だと感じました。