Since the Industrial Revolution, Earth’s temperature has been on the rise, and that rise has accelerated rapidly since 1975. Climbing temperatures harm human health, ecosystems in the sea and on land change, and the risks of natural disasters such as droughts and floods increase. The impacts of climate change are wide-ranging. One claim that has drawn attention in recent years is that climate change is linked to an increase in conflict.

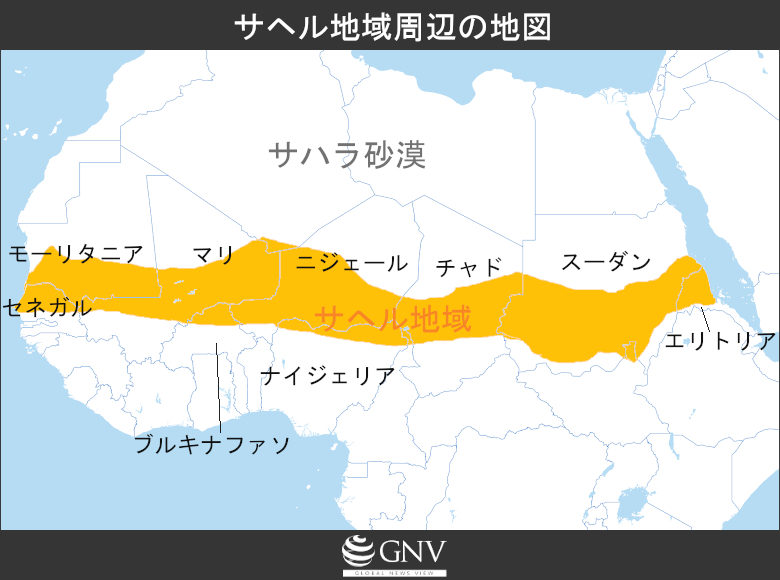

This article looks at the Central Sahel region of Africa as one such example. The humanitarian crisis in Africa’s Central Sahel was Selected by GNV as the top story in the Top 10 Hidden Global News Stories of 2020, ranking 1st. In this region, the intensification of conflict has created an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. In addition, temperatures there are said to be rising at a pace 1.5 times faster than in other parts of the world. So what exactly is happening in the Central Sahel? Has the advance of climate change really led to more conflict and violence? We introduce the realities of conflict in the Central Sahel alongside the debate over the relationship between climate change and rising conflict.

Burkina Faso, at the Mentao Nord camp (Photo: Pablo Tosco, Oxfam / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Escalating conflict in the Sahel

The Sahel stretches east to west across the African continent. It is a harsh, semi-arid region with low rainfall extending from Senegal in the west to Eritrea in the east. In the Central Sahel, which includes countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, the region has been experiencing unprecedented levels of armed conflict, human rights abuses, and mass displacement. In the one-year period starting in 10/2019, more than 6,600 people living in this region were killed, around 7.4 million fell into food insecurity, and about 150 medical facilities and 3,500 schools were forced to close. Why has the damage grown so severe? Let’s look at the timeline.

Created based on a map by Voice of America

The conflict that continues to this day traces back to the 2011 collapse of Muammar al-Qaddafi’s regime in Libya. Tuareg people—Tuareg pastoralists who migrate across borders in the Sahel—had long faced repression by the Malian government and had sought protection in Libya. Qaddafi granted them protection and provided military training, and many Tuareg worked under him as soldiers and the like. However, with the collapse of the regime amid the wave of uprisings known as the Arab Spring, armed Tuareg returned to northern Mali seeking independence, formed the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), seized northern Mali, and later declared the independence of “Azawad” in the north. During this period, weapons used in Libya also flowed into Mali amid the chaos. Instability in Libya contributed to the escalation of fighting in Mali. In 2012, a military coup occurred, and Mali spiraled further into turmoil.

Amid this, al-Qaeda–linked extremist armed groups also grew in strength and declared the application of Islamic law in northern Mali. In particular, in the city of Timbuktu, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA) and Ansar Dine—extremist groups backed by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)—seized control.

In 2013, France—the former colonial power in the region—and later the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) intervened in the conflict. Working with the Malian army, they retook the north and ended rebel control. That same year, the UN Security Council authorized the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), a peacekeeping operation (PKO). However, the situation did not improve; armed groups shifted to guerrilla tactics. In 2014, France again launched Operation Barkhane, deploying 4,500 troops, and that same year the G5 Sahel—comprising Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, and Mauritania—was established to promote cooperation on development and security in West Africa. In 2017, a joint force was also formed.

While multi-country conflict raged in the north, local-level clashes were frequent in central Mali. Deteriorating security due to the conflict, the advance of extremist groups, and disputes over access to land are cited as key drivers.

The conflict did not remain within Mali. Al-Qaeda–linked groups expanded operations across borders and carried out attacks in Mauritania and Algeria. By 2015, the turmoil had spilled over into Mali’s politically unstable neighbors Burkina Faso and Niger.

In Burkina Faso in 2015, after the collapse of President Blaise Compaoré’s 27-year dictatorship, the establishment of a transitional government, and a subsequent coup, the government fell into dysfunction. Extremist armed groups seized the opportunity to flow in from Mali. Other armed groups rooted in religious or ethnic ideologies also operated, and links to gold smuggling have been pointed out. Despite widespread violence by multiple armed groups, the government has repeatedly failed to respond, and it has also been unable to coordinate with humanitarian organizations.

A similar pattern has emerged in northern Niger, where the activities of armed groups organized along religious and ethnic lines and organized crime such as drug trafficking and human smuggling—fueled by a fragile economic base—are rampant. The government has been unable to properly regulate these crimes.

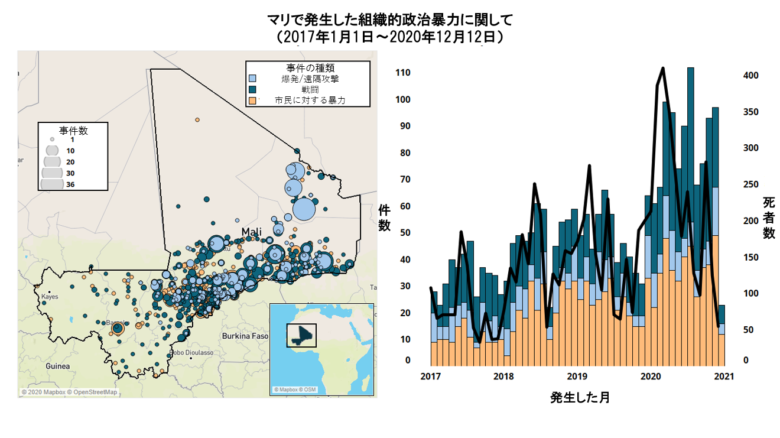

ACLED graphic with Japanese translation added

Due to instability in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, the number of violent incidents linked to extremist armed groups in the Central Sahel is said to have increased sevenfold between 2017 and 2020. Under the banner of counterterrorism against these groups, security forces in the three countries have also carried out serious human rights abuses against civilians, including extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, and torture. With no end in sight to the instability, MINUSMA’s mandate has been extended to July 2021.

Is climate change a driver of conflict?

Some have argued that environmental issues lie behind the instability described above—that climate change is deeply connected to conflict in the Central Sahel. The argument focuses on the idea that rising temperatures have led to more frequent droughts and desertification in an already arid region, reducing land suitable for farming and pastoralism. Competition over the remaining scarce land and water then intensified, escalating conflict. In fact, in 2007 UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon described the Darfur conflict in Sudan, where disputes over water resources were occurring, as the “first climate change conflict.” Research has also predicted that “a 1% increase in temperature raises the incidence of civil war by 4.5%, and that by 2030 conflicts in the Central Sahel will increase by 54%.” study

Arid lands in northern Mali (United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

However, multiple researchers argue that climate change is not directly linked as a cause of conflict in the Central Sahel. Professor Tor Benjaminsen of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences points out that desertification is not occurring in the Central Sahel in the first place. Because there is no desertification, the land is not being depleted, and thus climate change is not contributing to conflicts over scarce arable land, he argues. While severe droughts occurred in the Central Sahel during the 1970~1980s, greening has been observed in the region since. He explains that, as a long-term pattern, there is no ongoing increase in land that is entirely uncultivable. He also notes that although dry-season temperatures have indeed risen, the rainy season remains comparatively cool, so higher temperatures have had little effect on agricultural activities that occur in the rainy season. In addition, NASA, using satellite imagery of the Central Sahel’s deserts, has concluded from the images that desertification is not occurring.

Why, then, has the “myth” that “desertification is happening” and “desertification causes conflict” arisen and spread so widely despite so many researchers and institutions rejecting it? Its origin goes back to the colonial era. The notion of an environmental problem called desertification provided the colonial powers with a pretext to manage Africa’s natural resources. Behind this was a desire to manage nature on behalf of local people and exploit natural resources for their own ends —a political calculus.

Even after decolonization, “desertification” continued to be invoked in a different guise. For international organizations such as the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), desertification was an issue that easily drew attention, partly because there are few opponents to anti-desertification measures. Policies that hinder industrial development may prompt backlash, but few beyond politically powerless farmers and pastoralists object to policies like planting more trees in areas where they live. Such measures also enable an expansion of state-owned land. Desertification was thus spotlighted as a manageable, relatively non-contentious issue that avoided overtly political conflict. For African governments and NGOs, it also provided an avenue to secure funding to halt desertification. In this way, the “occurrence of desertification” has been conveniently used by various actors.

Women farming around Lake Bam, Burkina Faso (Ollivier Girard, CIFOR/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

What are the fundamental causes of the conflict?

If climate change is not directly causing the conflict, what are the fundamental drivers in this region? As noted, the turmoil was sparked by the fallout from the collapse of Qaddafi’s regime, which intensified fighting in northern Mali. Let’s look at the conflict in its historical flow. The Central Sahel, including Mali, is home to diverse ethnic groups, and friction over land and water between nomadic pastoralists and settled farmers has long existed. There were mechanisms to prevent most disputes from escalating into major conflict, and this alone would not have led to the current levels of violence.

So why is violence intensifying now? A key background factor is the failure to build a constructive relationship between nomadic groups and the governments that administer the territories over which they range. France, the former colonial power in West Africa, settled pastoralists like the Tuareg, who move across borders, and many lost access to the land they needed for their livelihoods. Much of the land came to be treated as public, under the banner of increasing forests and preventing desertification. Governments promoted commercial agriculture on such lands. After independence from France, Mali maintained this stance, prioritizing policies favoring farmers and neglecting pastoralists.

When friction arose between pastoralists and farmers, government institutions should have played a fair role in resolving disputes. Instead, corruption and graft were rampant among politicians and legal institutions in Mali, and disputes between pastoralists and farmers were resolved not impartially but monetarily. Grievances among pastoralists and tensions between pastoralists and farmers grew. Even when they tried to address conflict seriously, widespread poverty and fiscal constraints prevented fundamental solutions. Government institutions thus fueled and worsened the small sparks that had long existed between farmers and pastoralists. Tuareg (pastoralist) armed groups, inflamed by years of unequal treatment, launched independence movements, and extremist and jihadist groups intervened amid state dysfunction.

France’s presence also looms behind the Malian government’s dysfunction. Even after West African countries gained independence, France repeatedly intervened militarily in the region, driven by a political intent to build a favorable, beneficial political order for France. If a regime or group served France’s interests, Paris would support its survival, even if it was authoritarian. For example, under the pretext of counterterrorism in the Central Sahel, France supported the MNLA to secure its own access to resources. The real aim was to gain leverage over the Malian government. An expanding MNLA would weaken Bamako, pushing it to seek unconditional support from France—allowing Paris to dictate terms. Malian politicians, in turn, continued to adopt policies favorable not to citizens but to France, to prolong their own political careers. Thus, the political calculations of the former colonial power are deeply entwined with this conflict.

Niger, military training (USAFRICOM / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Outstanding challenges

As we have seen, climate change may not be a direct cause of conflict. However, it is certainly a factor exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in the Central Sahel, including by driving food insecurity. Regions with unstable political, economic, and legal systems are less able to adapt to short-term environmental changes, experience greater disruption, and have weaker capacity to recover. As climate change advances, further deterioration of the humanitarian situation is likely unavoidable.

Climate change is undoubtedly one of the key challenges of our time. But we must be especially careful not to assign sole responsibility for conflict in the Sahel to climate change. Doing so diverts attention from the political root causes of conflict. If all blame is placed on the external factor of climate change, it becomes impossible to press local power holders in the Central Sahel and former colonial powers still exerting influence, like France, to address the fragility of political institutions. “Climate change” becomes a convenient justification for conflict.

Moreover, even if desertification is not currently observed, the impacts of climate change are expected to intensify, with dramatically shorter rainy seasons and more frequent extreme downpours projected. If that happens, countries with fragile political and economic foundations will not escape devastating blows to agriculture and livelihoods. Rather than accepting the simplistic logic that “climate change drives more conflict,” we need to keep searching for ways to address the complex political and historical problems in the background, while also focusing on the climate crisis that is intensifying humanitarian emergencies.

Writer: Anna Netsu

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

Reporting assistance: Tor A Benjaminsen (Norwegian University of Life Sciences)

この記事を読んで改めて、報道機関や情報を発信する側はその問題の背景を踏まえた伝え方をしていく必要があると感じました。

すごく面白い記事だと思いました。気候変動だけではなく、政治、社会的考えていく必要があると感じました。

アフリカについての知識がほとんどないなかで「アフリカの紛争は気候変動が原因だ」と言われたら鵜呑みにしてしまいそうで、不安を感じました。複雑な事象でも簡略化しすぎず、正しく理解できるような視点を身につけたいと思いました。

気候変動がアクターそれぞれの都合に合わせて悪用される可能性の指摘にハッとしました。また、気候変動→紛争増加という単純構造で問題を捉えてしまうのも危険ですね・・・。政治・法体制の整備など包括的なアプローチで問題に対処する重要性に気が付きました!でも、日本にいる私たち(しかも今はただの学生)が政治・法体制に影響を与えられることはほとんどないと思うので(SNSに発信する程度?)、やっぱり気候変動問題に対処することが間接的にもサヘル地方の安定に繋がるのではないかと思いました!