In July 2020, the UK government announced it would resume arms exports to Saudi Arabia, which had been suspended. As of December 2020, the U.S. government is moving ahead with preparations to export state-of-the-art fighter jets, unmanned drones, and more to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been accused of involvement in war crimes in the Yemen conflict, where the humanitarian crisis continues to worsen, and these exports have come under strong criticism from politicians and civil society in the UK and the United States.

In this way, large quantities of weapons manufactured far away are being bought and sold for conflict zones where human rights are under threat. Who is conducting the arms trade, and with what intent? And what problems accompany it?

Large quantities of bullets, Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: MONUSCO Photos / Flickr[CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

Overview of the global arms trade

First, let’s take a look at the state of the global arms trade. A wide variety of weapons are traded worldwide: from large items such as warships, military aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles (drones), missiles, and military vehicles, to small arms such as grenades, machine guns, and pistols. Weapons also include radar sites for air-defense surveillance and reconnaissance satellites that observe land and sea from space. With the exception of the many state-owned enterprises seen in China, most of the world’s weapons are developed and manufactured by private companies and purchased by national governments.

However, in cross-border arms trade, private companies are not free to trade without restriction. Companies must obtain export licenses and comply with limits set by the governments of the countries where they are based. In the United States, for example, there are frameworks such as Foreign Military Sales (FMS), in which the government negotiates and conducts arms transactions on behalf of companies with allies and others, and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS), in which private companies and foreign governments contract directly. Even under DCS, transactions above a certain amount require congressional approval. The UN Security Council can also impose restrictions, such as the ban on arms imports and exports to Iran for more than 10 years due to concerns over its nuclear program.

What about the value of transactions? According to a U.S. State Department report, the total value of the global arms trade averaged $181 billion per year from 2007 to 2017, a 65% increase over the 10 years since 2007. Which countries trade the most? In records from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) covering the 5 years from 2014 to 2018, the top 5 exporters were the United States, Russia, France, Germany, and China, in that order. Combined, these countries accounted for roughly 75% of total global arms exports.

Among them, the U.S. share is particularly large at 36%, and its exports expanded by 29% compared with the previous 5-year period ending in 2013. Behind this is an increase in exports to the Middle East and North Africa. Some 52% of U.S. arms exports go to countries in the Middle East and North Africa, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and in the 5 years to 2018, exports to these countries were up 134% from the previous 5 years. By contrast, Russia, the number 2 exporter, has seen its exports decline. Russia’s share between 2014 and 2018 was 21%, still significant, but down 6 points from 27% in the preceding 5 years. A large drop in exports to India and Venezuela—key customers for Russia—led to an overall 17% decrease. However, exports to the Middle East and North Africa increased for Russia as well, much like the U.S. Russia mainly exports to Egypt and Iraq in this region, and exports to these two countries rose by 150% and 780%, respectively. The expansion of U.S. and Russian arms exports to the Middle East and North Africa was likely driven in part by surging demand for weapons amid the conflict with IS (Islamic State), which maintained strongholds spanning Iraq and Syria.

What about imports? Over the 5 years from 2014 to 2018, the top 5 importers were Saudi Arabia, India, Egypt, Australia, and Algeria, in that order. Combined, these five countries accounted for about 35% of global imports. While arms exports are dominated by a limited number of countries, imports are carried out by a relatively wider range of states. By region, Asia and Oceania and the Middle East and North Africa import the most, accounting for 40% and 35% of the global total, respectively. While most regions saw decreases, only the Middle East and North Africa showed an upward trend: comparing the 5 years to 2018 with the previous 5 years to 2013, imports increased by 87%.

A Canadian-made Light Armored Vehicle used by the New Zealand military, Afghanistan (Photo: New Zealand Defence Force / Flickr[CC BY 2.0])

Which companies manufacture weapons? In 2018, SIPRI published data on the world’s top 100 arms-producing companies by annual sales, and the United States stood out. Of the 100 companies, 42 were American, and U.S. firms accounted for 57% of the $398.2 billion in total sales. The top manufacturer was U.S.-based Lockheed Martin; second and third were also American—Boeing and Raytheon. Their main products are military aircraft (Lockheed Martin and Boeing) and missiles (Raytheon). In the top 10, non-U.S. firms included the UK’s BAE Systems (4th, mainly military aircraft), Airbus Group headquartered in the Netherlands and France (7th, military aircraft), France’s Thales (8th, aircraft carriers), Italy’s Leonardo (9th, military aircraft), and Russia’s Almaz-Antey (10th, air-defense missiles). Although excluded from the ranking due to data gaps, it is believed likely that three Chinese arms makers would rank in the top 10. This concludes the overview of the arms trade.

Arms and armed conflict

Next, let’s focus on the relationship between the arms trade and conflict. The number of armed conflicts varies by definition, but according to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), there were 54 ongoing conflicts in 2019. Here, the role played by the arms trade is substantial. Because most conflict-affected countries do not manufacture weapons domestically, conflicts are enabled by weapons that are produced and traded internationally, as described above.

Weapons may be purchased for national defense and used defensively, or they may be bought to carry out offensive operations domestically or abroad. Either way, once conflict begins, not only soldiers but large numbers of civilians are inevitably harmed. Civilians are often deliberately targeted, making normal life impossible. Including refugees and internally displaced persons, the number of people uprooted by conflict and persecution exceeded 80 million—about 1% of the world’s population—by mid-2020. Even outside of an active war, governments sometimes deploy weapons to suppress peaceful demonstrations and assemblies by citizens. For example, during unarmed protests in Nigeria in 2020, security forces opened fire, killing at least 56 people; bullets recovered at the scene were reportedly ones the Nigerian government had purchased from Serbia.

Soldier with a rifle, Bogotá, Colombia (Photo: Pikist)

Even if sellers intend to trade weapons strictly for defensive purposes, they are not guaranteed to be used accordingly. Weapons can later be resold or seized by domestic or foreign anti-government forces or terrorist organizations and used in ways that contradict the original purpose—such as attacks on civilians or the commission of war crimes. Sometimes the weapons are even turned on the very country that exported them. After the 2003 invasion and occupation, the United States exported large quantities of weapons to Iraq; when IS rose in 2014, many of these weapons ended up in the group’s hands and were used against U.S. forces in Iraq. Some weapons have very long lifespans—such as the U.S. B-52 bomber, last delivered in 1962 and slated to remain in service until 2050 through repeated repairs—and are not disposable items. Once purchased, there is no assurance, and limited ability to control, how weapons will be used across borders over long periods of time.

The suffering caused by conflict is not limited to direct use of weapons. Food shortages are also chiefly driven by conflict. In conflict zones, farming becomes impossible, and price spikes can make food unaffordable. In 2019, the World Food Programme (WFP) assessed that 135 million people worldwide were in “crisis” or worse regarding food security, with conflict the primary driver. In 2020, for example, in West African countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, instability from conflict was projected to push 4.8 million people into acute food insecurity. In addition, water scarcity worsens with conflict. Wells may be targeted in airstrikes to cut off the enemy’s water supply, and even without direct targeting, large-scale bombardment and contamination can render water sources unusable. Access to healthcare is also impeded: hospitals in conflict zones suffer damage from airstrikes and become inoperable, and some shut down out of fear of attack, making it difficult to receive medical services in emergencies. In these ways, the conflicts facilitated by the arms trade threaten civilians’ lives.

Bullet holes in a window, Mogadishu, Somalia (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The arms trade and corruption

In the arms trade, there are notably many reports—more than in other industries—of corruption cases in which exporters’ manufacturers bribe officials in importing countries to secure contracts. One case where staggering sums were allegedly paid in bribes is the Al-Yamamah arms deal concluded between the UK and Saudi Arabia in 1985. In the competition over whether the UK or France would export fighter jets to Saudi Arabia, the British manufacturer British Aerospace (now BAE Systems) allegedly secured the rights by handing large bribes to various stakeholders. To recoup the extraordinarily high bribes, the deal price was reportedly marked up by 32%.

The motivation for such large-scale bribery on the exporter’s side lies in the size of the contracts. Large arms exports present major opportunities for both manufacturers and exporting governments, and they will use any means to beat rival countries and firms to the deal. The largest arms deal in history was a 2017 agreement between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia worth a staggering $350 billion over 10 years. Exporting governments and manufacturers join forces in negotiations to achieve economic benefits and strengthen security ties, increasing secrecy; if the importing country is a dictatorship with weak domestic oversight, the hurdles to bribery fall even further.

Russian military helicopter Mil Mi-28 (Photo: Dmitry Terekhov / Flickr[CC BY-SA 2.0])

Beyond straightforward bribery, “offset” agreements also facilitate corruption. Offsets are conditions offered as part of negotiations—benefits provided in return for the contract. For example, an arms maker may promise to invest in the importing country’s industries, or propose local production to create jobs—an “extra” that helps the importing country’s politicians win public support for an expensive arms purchase. In one case, a German arms manufacturer contributed part of the production costs for the film “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom” (based on former South African President Nelson Mandela’s autobiography) in connection with selling submarines to South Africa. Offsets can benefit both sides and are not inherently problematic, but many companies refuse oversight on the grounds of commercial secrecy, and the politicians deciding on imports often have close ties to companies, making these agreements prone to corruption.

When large bribes change hands, importing officials are also less discerning about what they buy. They prioritize contracts with companies and governments that pad their own pockets, leading to purchases of overpriced, underperforming weapons—or even items they do not need at all. In the South African example above, the country purchased expensive submarines from Germany, but high maintenance costs have left them barely used, prompting questions about whether they were ever necessary at all. National budgets wasted on costly, unnecessary weapons could have supported healthcare, infrastructure, and education. The harms caused by corruption in the arms trade are substantial.

Unmanned aerial vehicle on display at an arms fair (Photo: rhk111 / Wikimedia Commons[CC BY-SA 4.0])

Background to the problem

As described above, the arms trade threatens people’s safety and fosters corruption that imposes unnecessary burdens on taxpayers. Why, then, does the value of transactions continue to rise? First, international politics. For military powers, there are advantages to selling arms to, and providing military assistance for, allies and close partners to expand their military capabilities. The choice of supplier by importing countries also involves political maneuvering. For example, in October 2020, Turkey—a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)—tested a surface-to-air missile system purchased from Russia, which opposes NATO, drawing strong condemnation from the United States.

Second, the business angle: the presence of the military-industrial complex, namely, the political and economic structures that promote domestic weapons production and exports for the benefit of exporting-country firms and officials. This structure is built by those who profit from the arms trade—government officials, the military, and private companies. These private actors include not only major arms makers and their subcontractors, but also industries that supply materials—such as steelmaking and electronics—that are not directly part of the defense sector. In recent years, IT companies such as Google have also supported military operations by providing AI technology to identify and analyze imagery from military drones. These actors are deeply interconnected: military officials take post-retirement positions at arms manufacturers, and firms and industry groups lobby governments to incorporate their products into national defense. Promoting weapons production and sales helps politicians in elections—by creating jobs that win public support and by delivering favorable policies that attract campaign contributions. Private companies, for their part, secure massive contracts. If each actor seeks to maximize their own benefit, the system rewards continued weapons production and exports—at the expense of taxpayers and the victims of armed conflict.

Third, the use of the arms trade as a stage to showcase national technological prowess. So-called “neutral” Sweden is one such example, promoting its large defense industry as part of national branding. For these reasons, those involved in weapons production and export have promoted the arms trade, generating uncontrollable associated problems.

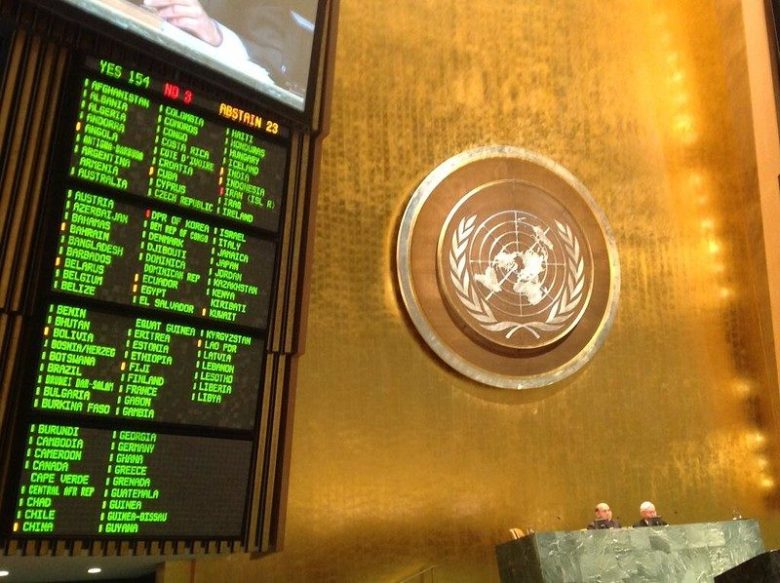

In April 2013, the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) was adopted by a large majority at the UN General Assembly (Photo: Norway UN(New York) / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Addressing the problem

Are the problems caused by the arms trade simply left unchecked? Not entirely. In 2014, the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) entered into force. Concluded to prevent illicit trade in conventional arms that harms states’ security and society, economies, and humanitarian conditions, it has been ratified by 110 countries as of December 2020. States parties to the ATT must establish domestic systems to regulate international trade; they must not authorize arms exports where there is a high risk of use in human rights violations or war crimes. They are also obligated to implement anti-diversion measures, keep records of transactions, and report these measures to the treaty secretariat. Although many countries had domestic rules on arms trade, this was the first time international regulatory standards were required. It is true that many states now recognize the risks associated with the arms trade.

However, among the two largest exporters, the United States has not ratified the ATT and Russia is not a party, calling into question how effective the ATT can be in addressing the problems of the arms trade. Even in ratifying countries, regulations are not always effective. The risk of human rights abuses can be interpreted flexibly, allowing exports to slip through. Many Western European countries that have ratified the ATT—including France, Germany, and Italy—and Canada continue to export large volumes of weapons to Saudi Arabia, which is alleged to be involved in human rights violations and war crimes in the Yemen conflict.

Constraints on the arms trade do not come only from international treaties. Politicians, civil society groups, and the media also play vital roles. For example, the U.S. exports mentioned at the beginning of this article drew strong protests from human rights organizations. In the past, a South African dockworkers’ union refused to unload a ship, successfully blocking a Chinese arms shipment to Zimbabwe, where abuses were reported. The media, through investigation and reporting, exposes problems in the arms trade—corruption and human rights violations in destination conflict zones—and informs the public. In 2016, journalists revealed a case in which employees of German firearms manufacturer Heckler & Koch illegally exported guns to Mexico for example. If governments push the arms trade in concert with big business, civil society oversight is essential.

Guns being destroyed, Kosovo (Photo: Arben Llapashtica / Wikimedia Commons[CC BY-SA 3.0])

It is legitimate for countries without the technology to manufacture weapons to import equipment for national defense and policing. For technologically advanced countries, producing and exporting weapons is also a form of economic activity. However, the arms trade—expanded by intertwined political objectives and commercial interests—becomes a breeding ground for large-scale corruption and, in destination countries, morphs into attacks on civilians, food crises, water shortages, and the collapse of healthcare systems, threatening countless lives. Necessity and benefits can never justify endangering people or allowing the powerful and large corporations to line their pockets with taxpayers’ money. A structure that lets the powerful pursue profit while imposing outsized harm and burdens on those in vulnerable situations must be promptly reexamined.

Writer: Suzu Asai

Graphics: Suzu Asai

武器の生産・売買それ自体は正当化される部分があるけれど、武器貿易に対する権力者たちの私欲は容認できることではないと感じました。複雑な現象について分かりやすく説明されていて、とても読みやすかったです!

武器の輸出について数字で見ると、改めてその規模の大きさを思い知りました。権力者たちの欲とそれに反した現地のダメージのギャップをすごく感じた内容でした。流れが読みやすくわかりやすかったです!

武器とビジネスや国際関係とのつながりについて理解することができました。武器は戦争の道具であると同時にお金儲け、権力誇示、国際関係のコントロールの道具ともなってしまっているのですね。武器を製造し、動かすことで生み出される一部の組織や人々への利益や付随価値が大きいからこそ、問題を解決することが難しくなってしまっている現状が分かりました。一度軍事産業として、国の経済活動の中に組み込まれてしまうと、武器製造・輸出の減少や停止が雇用や賃金といった部分にも影響してしまうため、なかなか状況を動かすことは難しいのだなと感じました。