On June 12, 2020, it was announced that a truth commission would be established in Sweden. A truth commission is set up at the national level to investigate historical injustices suffered by groups subjected to human rights violations and political repression, with the aim of future reconciliation. The truth commission to be established in Sweden aims to shed light on the history and reality of the discrimination that the Indigenous Sami, who have traditionally lived in the Arctic region, have long faced from the government. This will be the third country to establish a truth commission concerning the Sami, following Norway in 2017 and Finland in 2019. What kinds of discrimination have the Sami suffered up to the present day, and what new environmental and development issues are they currently facing?

Sami Parliament in Norway (Photo: Illustratedjc/Wilimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

目次

Who are the Sami

The Sami are Europe’s largest Indigenous people, who have traditionally lived across the northern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula to Russia’s Kola Peninsula. They are believed to have inhabited the region at least since 11,000 BCE, and their population is estimated at 80,000 in total: 50,000 in Norway, 20,000 in Sweden, 8,000 in Finland, and 2,000 in Russia. However, these statistics are based on identity, and because no accurate surveys have been conducted in each country, the exact population is unknown. Traditionally, they practiced a polytheistic religion emphasizing connection with the earth. The Sami language has long been used as the community language. Although Sami is said to lack clear linguistic boundaries between adjacent dialect regions, at least 10 dialects have disappeared due to declines in the number of speakers. In recent years, opportunities to learn and use Sami are limited, and few young people speak it. As of 2001, the number of speakers was said to be 25,000–30,000.

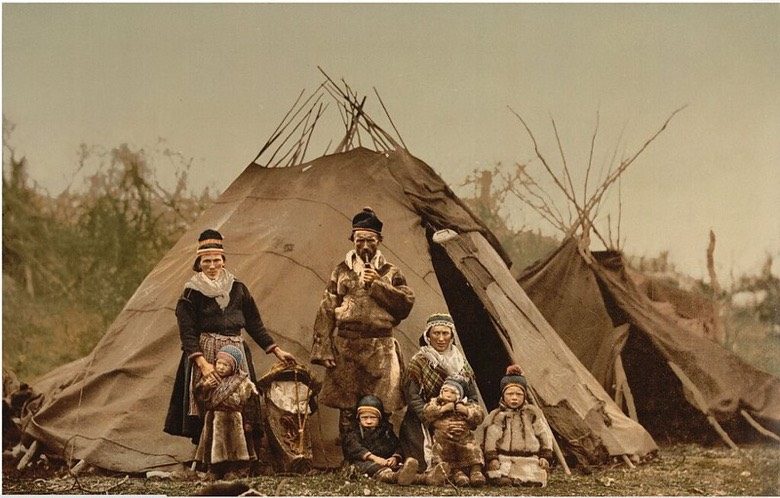

The Sami who lived in the far north developed a way of life adapted to the harsh, cold tundra climate, and although they had trade relations, they remained independent rather than being incorporated into surrounding states. For centuries, they maintained lifestyles such as hunting and gathering, fishing, and reindeer pastoralism. In particular, the Sami and reindeer herding are culturally inseparable. Sami who engage in reindeer pastoralism form settlements of about 5 to 6 families and live a nomadic life, moving in step with the herds as they seek food by season. They made their living by utilizing reindeer as a resource—eating the meat, using the hides for clothing, and selling products. Today, however, only a small minority live solely by reindeer herding, and most Sami have moved away from their ancestral lands and traditional ways of life since before state encroachment, living in urban areas or earning a livelihood outside of herding and fishing. Even those living in traditional Sami settlements often make their living in the service sector.

The Sami also have parliaments that address Sami issues, consult with states, build consensus as the Sami people, and work to protect culture and language. Sweden, Norway, and Finland each have a separate, Sami-specific parliament distinct from the general national parliament. In particular, these three countries are working not only to establish the status of the Sami as a minority but also to conclude treaties to secure wider autonomy for the Sami. The Sami possess their own culture, language, and parliament. Yet, looking back at history, their existence and communities have been pushed into a vulnerable position through years of discrimination and forced cultural assimilation. Even today, the rights of the Sami are disregarded in many instances.

History of discrimination

As noted above, the Sami originally lived independently in the Arctic region, separate from today’s Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. From the 15th century onward, however, Sweden and Norway turned their attention to Sami lands for their resources and sent expeditions. These countries imposed unilateral systems aimed at displacing the Sami from their lands, such as imposing taxes for settlement, and the expedition members engaged in actions like the overhunting of reindeer. Some Sami, deprived of their traditional way of life, were forced to give up making a living through herding or fishing. This event marked the beginning of increasingly severe demands for cultural assimilation.

In 17th-century Sweden, Christianization was forced upon the Sami. Those who did not comply with conversion to Christianity were fined, imprisoned, or even sentenced to death, effectively forcing them to attend church services. This nearly completely destroyed the traditional Sami religion. In 19th-century Norway, the government seized lands on which the Sami had lived, and also banned the use of the Sami language and customs, while forcing conversion to Christianity. Prior to this, education had been conducted in Sami, and religious texts were also written in Sami. Due to the Norwegian government’s assimilation policies, children were educated in Norwegian and had their names changed to Christian ones, leading to the harsh suppression of their distinct culture and language. As a result, many Sami dialects went extinct. In the first half of the 20th century in Norway, laws were enacted obligating the transfer of Sami land to the government, and further proactive measures were taken to eradicate the Sami and their culture.

A traditional Sami family (Photo: tonynetone/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

After World War II, the International Labour Organization (ILO) concluded the Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention (No. 107) (※1) in 1957. This was the first international document adopted to free Indigenous peoples from oppression and discrimination. However, the convention assumed the integration of Indigenous peoples into the dominant society, strongly implying that cultural loss was inevitable. Some Indigenous peoples opposed this, arguing from a human rights perspective that forced assimilation should be stopped. Thus, in 1989, Convention No. 107 was revised into the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169) (※2). This international instrument is aimed at restoring the rights of Indigenous peoples worldwide, recognizing their right to self-determination within the state, and setting standards for governments regarding all Indigenous rights, including rights to land. However, not all countries that had ratified the convention prior to the revision ratified the revised version. Citing the reason that granting the Sami the right to self-determination would weaken state control, only Norway ratified the revised convention, while Sweden, Finland, and Russia did not.

With the end of the Cold War in 1989, cross-border movement with Russia—which had been difficult during the Cold War—resumed, and in the context of global movements for Indigenous rights from the 1980s to the 1990s, in the late 1990s, laws recognizing the Sami as Indigenous were passed in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. However, in Sweden and Norway, although the constitutions guaranteed the protection of culture and language and recognized Sami parliaments, the laws were not implemented in practice, and tacit discrimination continued. Finland recognized the Sami as a people, but since it has not ratified ILO Convention No. 169, rights related to Indigenous land have remained unrecognized; Russia mentions in its constitution the goal of economic development for Indigenous peoples, but the government has not implemented it. In all of these countries, the restoration of the Sami’s rights as Indigenous peoples has been neglected. Since 2000, Sweden has officially recognized Sami as a minority language, and in 2011 it recognized the Sami as a people, but laws concerning Sami land and rights have not been enacted, and discrimination persists to this day.

Members of the Saami Council presenting at the Arctic Council (Photo: arctic_council/Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

Environmental issues threatening livelihoods

In addition to the discrimination described above, environmental problems and climate change in recent years have also greatly affected Sami life.

One such issue is radioactivity. In 1986, an explosion occurred at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine. After the accident, a cloud containing radioactive materials spread over a wide area of Europe, including Norway, and radioactive substances fell to the ground with rain and snow. These radioactive substances are readily absorbed by lichens and mushrooms, and lichens are the winter food of reindeer. As a result, since the Chernobyl accident, radioactive materials accumulated in reindeer bodies as they consumed contaminated lichens, and even 30 years after the accident, it has become clear that in Norway, radioactive substances far exceeding the standard levels have been detected in reindeer. Reindeer meat is widely consumed in the Scandinavian countries and was an important source of income for the Sami who make their living through reindeer pastoralism. However, meat from reindeer in which radioactive substances were detected could not be sold, dealing a major blow to the livelihoods of Sami who herd reindeer.

Furthermore, climate change, a major global issue, is also greatly harming reindeer. The Arctic, in particular, is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet. For example, in Sweden, the average temperature across the country has risen by 1.64 degrees compared to the pre-industrial era. In mountainous regions, this trend is even more pronounced: it has been announced that the average winter temperature from 1991 to 2017 was 3 degrees higher than the average from 1961 to 1990. One of the problems caused by this warming is a shortage of food for reindeer. Rising temperatures cause some snowfall to fall as rain, and subsequent drops in temperature form a thick layer of ice on the ground. Reindeer generally migrate seasonally in search of food, but their food becomes trapped beneath this thick layer of ice. In the Arctic, the first snow falls in autumn, making winters long, and at the same time extending the period during which reindeer cannot access food. In their summer pastures the grass has been grazed down, and when they move to their wintering grounds they may not find food for long periods, increasing the risk of suffering from food shortages and dying from starvation. Furthermore, because the first snow falls early in the Arctic, winters are long, and the period without food for reindeer becomes prolonged. As a result, winter food shortages for reindeer are severe, and the risks of starvation and other dangers increase.

A herd of reindeer (Photo: Mats Andersson/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

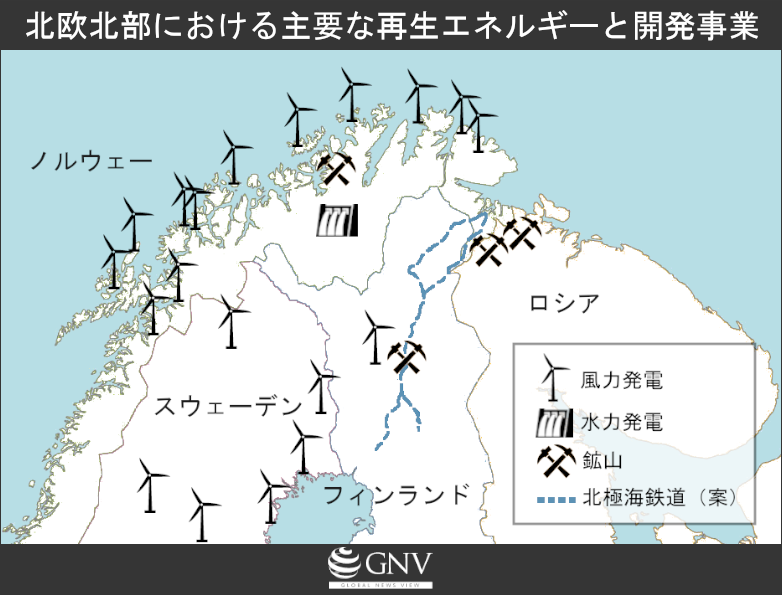

Moreover, climate change is melting glaciers and making various industries and shipping feasible in the Arctic, which also threatens Sami life. One example is the Arctic Railway construction plan. In recent years, sea ice has been melting due to warming, and Arctic sea routes are expanding. In response, Finnish entrepreneurs sought to promote economic development in northern Finland, and in 2019 proposed building a railway from Norway to Finland to transport mining products, oil, and gas. However, constructing the railway could take away pasturelands from the Sami, lead trains to cross reindeer herding routes, and cause collisions between moving trains and reindeer—potentially harming every aspect of Sami livelihoods tied to reindeer pastoralism. Furthermore, once the railway opens, infrastructure will be improved and new industries are expected to advance along the route, further depriving the Sami of the benefits of land rights.

In Finland, logging is also being carried out on a large scale. Forests in Finland account for less than 1% of the world’s forests, yet as of 2018 the country ranked 9th in paper production, indicating that forestry and the paper industry are thriving. Logging takes place in vast tracts of state-owned land where herds of reindeer graze, leading not only to large-scale deforestation but also to degraded plant cycles and the destruction of diverse ecosystems. As mentioned earlier, Finland has not ratified ILO Convention No. 169, and companies operated forestry without regard for the environment or the Sami. In response, demonstrations and lawsuits occurred across Europe, and in 2010 the Finnish government agreed to protect the forests, promising that they will be preserved at least until 2030. As these examples show, Sami life is heavily affected by climate change, environmental destruction, and the push for resource development by states.

“Green colonialism”

As climate change worsens, the production of renewable energy and electric vehicles is seen as a key part of the response. However, advancing renewable energy and vehicle production can also negatively impact the Sami’s traditional way of life.

The dam built on the Alta River (Photo: Statkraft/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Around 1980, hydropower was spotlighted as a renewable energy source, and a proposal was made to build a dam on the Alta River in northern Norway. However, the Alta River flows through reindeer pasturelands, and the dam posed risks of submerging Sami settlements and blocking reindeer herding routes. In response, Sami activists and Norwegian environmentalists protested to block the dam and the roads needed for its construction. Police were dispatched and arrests were made, but resistance continued. Ultimately, however, construction could not be halted, on the grounds that the Sami did not hold ownership rights to the pasturelands. It is said that the protests and their impact later led to constitutional amendments guaranteeing the protection of Sami language and culture and to laws recognizing political representation. This event also brought wider recognition that Sami livelihoods were being threatened in the name of promoting renewable energy. Wind power has likewise drawn attention as a renewable energy source, and wind power projects are underway in Norway. As with the dam that caused issues of submerged settlements and blocked pasturelands in the 1980s, wind facilities built in the mountains take away more land from the Sami, further shrinking their living space.

With rising global demand for renewable energy, demand for the mineral resources needed to produce and store that energy has also increased, and mining development is advancing. Copper and cobalt used in batteries for electric vehicles and in wind turbines are a typical example. While a smartphone battery requires around 10 grams of cobalt, a battery for an electric car requires up to 3 kg, far more. Increasing production of EV batteries requires vast amounts of copper and cobalt, prompting the search for new mining sites and expansions of existing ones. In several countries, resource-rich regions overlap with Sami territories, meaning mining development also affects Sami life. Russia has the Nikel and Zapolyarny mines; Finland has the Kevitsa mine. And the Norwegian government, despite opposition from the Sami Parliament, approved plans to develop a copper mine in Finnmark to maintain its reputation as a world-leading environmental nation. While some support this as promoting a green economy, others condemn it as one of the most environmentally harmful projects in history. There is also the problem that dumping mine waste destroys ecosystems.

These moves to produce energy, machinery, and related infrastructure perceived as environmentally friendly may appear laudable at first glance. But behind them, Sami homelands and livelihoods—as well as the nature and ecosystems there—are being gradually taken and destroyed. Environmental problems created by the socially powerful and the profits sought from their solutions drive “green” initiatives, but the costs are borne in the form of violations of the rights and interests of the socially vulnerable. Because this structure resembles colonialism, it is called “green colonialism.” To properly protect Sami life and culture, those undertaking development projects have an obligation to consult in good faith and sufficiently in advance, consider how to minimize negative impacts, and obtain consent before proceeding. However, as researcher Susanne Normann, who works on this issue, points out (※3), companies prioritize generating profits, and projects often move forward without sufficient understanding or time among companies and involved consultants. An “information asymmetry” arises between the knowledge the Sami possess about the delicate reindeer ecosystem and companies rushing to execute projects; as a result, development proceeds without addressing Sami concerns, and their livelihoods are threatened. The problem does not lie solely with companies, however. Ultimately, governments bear significant responsibility to safeguard the Sami’s foundational livelihoods. They have critical roles—such as regulations and permits from the planning stage, and provisions for compensation after implementation—yet in reality they are not fulfilling these roles adequately. She notes that complex, competing interests among various stakeholders lie behind the problem.

We have looked at the history of discrimination the Sami have faced and the issues they currently confront. Although the way they are treated has changed over time, discrimination persists, and their livelihoods are threatened both by climate change and by measures to address it. Mitigating climate change is necessary, but so is protecting Sami rights. How to balance the two is a difficult challenge. We should watch closely to see how things develop.

※1 Although the ILO’s Japanese title is 土民及び種族民条約, this is an inappropriate expression; here we refer to it as the Indigenous Peoples Convention.

※2 Although the ILO’s Japanese title is 原住民及び種族民条約, this is an inappropriate expression; here we refer to it as the Indigenous Peoples Convention.

※3 Interview with the author in October 2020

Writer: Mayuko Hanafusa

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa, Yow Shuning

With cooperation from: Susanne Normann (University of Oslo)

恥ずかしながら、この記事を読みまでサーミのことは全然知らなかったのですが、とてもわかりやすく解説されていて勉強になりました。単に差別があるというだけでなく、環境問題や気候変動対策としての再生可能エネルギーの開発など、様々な要因がサーミを妨げているのだと知ってとても驚きました。

再生可能エネルギーや自動車の生産を進めることはいいことばかりではありませんよね。サーミのような人々の生活に対して負の影響を及ぼさないように、これからグリーン政策がどのように進むべきなのかは重要な課題だと思います。

「グリーン植民地化」という言葉は初めて知りました。グリーン化は環境には良いといつも言われていますが、このような問題もありうることも考えながらグリーン化を考えるべきですね。

現在にいたるまで差別が続いていることに衝撃を受けた。

同じ人間であるにも関わらず、民族の違いをもって見下し支配してよいと思う傲慢さが悲しい。

環境破壊を代表する森林伐採、環境問題に貢献するための風力発電、どちらをとってもサーミの生活を脅かすので、サーミの生活保護と経済活動の両立の難しさを実感した。

気候変動の影響を受けているが、気候変動対策を行うことでもサーミの人々の生活に影響を及ぼすことに驚きました。

サーミの人々の生活を守りつつ、気候変動の対策を行うことは難しい問題だと感じました。

4か国にまたがって一つの民族が居住しているって大変ですね…

気候変動に対する取り組みはもちろん大切だし推進されていかなければならないと感じますが、アンフェアな形でサーミの方々の生活が脅かされてしまうのは良くないと思いました。対等な関係で気候変動への取り組みとサーミの生活のバランスの取れた計画を進めていって欲しいと思いました。