On 2021/9/14, New Zealand’s Māori Party launched a petition to change the country’s name to “Aotearoa.” “Aotearoa” means “the land of the long white cloud” in the Māori language and here refers to New Zealand as a whole. The Māori Party is a political party that claims to represent the Māori, the Indigenous people of this country. As of 2020/6, an estimated about 850,000 people, accounting for 16.7% of the domestic population, identify as Māori. The petition gathered 40,000 signatures within 36 hours of its launch, and by the end of 2021/9 it had surpassed 60,000 signatures. According to a broadcaster’s opinion poll, 41% of respondents want Aotearoa to become the official country name, or to be used alongside New Zealand. What lies behind this movement? This article reviews New Zealand’s past and explains developments up to the present.

Members of the Māori Party meeting with the leader of the New Zealand National Party (Photo: nznationalparty / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

History of New Zealand (up to 1840)

According to the prevailing view, around 1300, people traveled by canoe from the Polynesian islands of the South Pacific and arrived in the north of what is now called New Zealand. As the population grew, people moved across various parts of the 2 islands and formed distinct communities. Disputes between communities were resolved through negotiation or military means. As they had no written language, myths and folktales were passed down through songs and stories.

Thereafter, from the 17th to the 18th centuries, European explorers reached New Zealand. Notably, the present country name, New Zealand, was given by Europeans who visited the area in the 17th century. From the early 1800s, European whaling ships visited the north of New Zealand, and trade developed between Europeans and the Indigenous people. Europeans sought food and local labor, while Indigenous people sought weapons such as muskets. Until people arrived from Europe, there was no collective term for the Indigenous peoples beyond their individual communities, but to distinguish themselves from those who came from Europe, they began using the Polynesian word “Māori,” meaning “ordinary” or “normal” as a name. Māori in turn began calling people from Europe “Pākehā” by that name. Later, Pākehā came to refer primarily to people of European ancestry. In this article we use Māori and Pākehā in this sense.

In the 19th century, Christian missionaries from Europe also became active. Through such contact, aspects of Western ways of life gradually spread among Māori. Missionaries received food and housing from Māori chiefs and in return provided muskets. As Māori communities that obtained guns clashed with others, an arms race known as the 1818–1840 “Musket Wars” broke out in New Zealand. It is said that about 20,000 people died in this conflict. Moreover, the number of people who died due to infectious diseases brought from Europe far exceeded the deaths from war: during the period of the Musket Wars, within the territory of present-day New Zealand, about 120,000 people died from ordinary causes such as illness.

As war and disease took their toll, the Māori economy was on the verge of collapse. At that time, Māori who had been cooperating with Pākehā (settlers mainly from Britain), and who were alarmed by France’s new interest in controlling New Zealand, saw chiefs of various Māori communities—who had previously sometimes fought over resources—unite to pursue the formation of a Māori state (※1). As trust had been built with British missionaries, Māori sought cooperation with Britain. In 1835, Māori chiefs issued a declaration of independence seeking the British monarch’s protection in return for having managed Pākehā in New Zealand.

Unhappy with this declaration, Britain put forward a large-scale settlement plan in the late 1830s and began to contemplate colonization of New Zealand. Alongside the settlement plan, the British government wanted to apply British law in New Zealand to manage new settlers. Meanwhile, Māori faced the problem of dealing with lawless Pākehā and external threats. In light of their respective circumstances, negotiations between the British government and Māori chiefs led to the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The treaty provided, among other things, that sovereignty would be ceded to Britain in exchange for protection of Māori from external threats, and that while Māori land rights would be guaranteed, an exclusive right of pre-emption to purchase Māori land would be granted only to Britain. However, after the treaty was signed, disputes over territory and sovereignty broke out between Māori and Britain despite the treaty’s existence. Some argue this was because the two sides differed over the scope of “sovereignty” in the treaty, while others contend that, after the treaty, economically powerful Pākehā promoted the acquisition of Māori land to a degree that stripped Māori of sovereignty beyond what was envisaged. In any case, issues over sovereignty and land rights between Māori and Pākehā have persisted into the present.

A reconstruction depicting the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi (Photo: Archives New Zealand / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Toward British rule

After the Treaty of Waitangi, as Britain’s land purchases advanced, the practical scope of British “sovereignty” in New Zealand expanded. Māori repeatedly petitioned Britain, asserting that the treaty’s provisions on land sales were not being honored, but to no avail. A British judge’s statement that the treaty was legally invalid has been seen as a symbol of how Māori rights were ignored. From the late 19th century, movements arose among Māori to revisit the treaty and demand the return of land, but negotiations with the British government repeatedly fell through. Debate over the treaty’s contents continues to this day.

Having extended its landholdings and wrested control of New Zealand, Britain established a colonial government and set up laws and institutions favorable to itself. As a result, Māori lost even more land, and in some places even their language and culture. Below, divided into land, socio-economics, and language/culture, we look at the situation Māori faced after the treaty was signed.

Before the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori held most of the land in the country. After the treaty, the colonial government used the right of pre-emption to buy land one after another, and by 1860 it owned 80% of the land in the North Island. Faced with the rapid loss of land and fearing subjugation to Britain, opposition to land sales arose, mainly among Māori. As disputes over land ownership in the North Island expanded, the New Zealand Wars broke out in 1860 and continued for 12 years, involving Pākehā who sought land sales, Māori who opposed them, and the colonial government.

In response to the wars, the colonial government enacted the Suppression of Rebellion Act, the New Zealand Settlements Act, and the Native Lands Act between 1863 and 1865. With laws designed to take Māori land, land belonging to Māori involved in the wars was confiscated, and by 1865 the colonial government owned 99% of the South Island, and parts of the North Island were also confiscated. Furthermore, land transfer laws enacted between 1865 and 1890 led to the transfer of ownership of more than 3 million hectares to the colonial government. As a result, by 1920 Māori held only 8% of the combined lands of the North and South Islands.

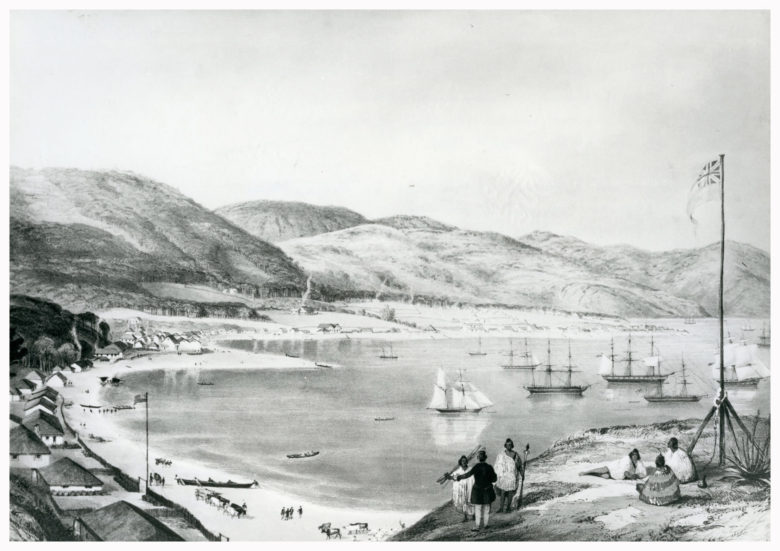

An 1841 impression of Wellington (Photo: Archives New Zealand / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Major changes also occurred in socio-economic terms. Triggered by the New Zealand Wars, the Māori population declined. Estimated at around 70,000 to 90,000 at the time of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the population continued to fall through the end of the 19th century, reaching about 42,000 in 1896 in decline. This was due not only to deaths in war but also to the impact of new infectious diseases brought by settlers, which increased the number of Māori who died before reaching adulthood in the background. Meanwhile, the Pākehā population kept growing, making Māori an ever smaller minority and reducing their economic resources and political influence.

What was the political situation? From 1853, the colonial government held the first elections for members of the lower house of Parliament. At the time, only landowners could vote, so many Māori could not participate. Māori owned land communally as communities and therefore did not hold individual title, which was a requirement for the franchise. In the first election, of 5,849 eligible voters, only about 100 were Māori. Later, based on a Pākehā view of politically assimilating Māori, from the 1868 election onward, 4 of the 37 seats were designated for Māori. The number 4 was extremely small compared with the population ratio of Pākehā and Māori, and a review of the seats did not occur for more than 100 years. Differences also existed between Pākehā and Māori in polling dates and voting methods.

Discrimination against Māori was evident in 20th-century policy as well; the old-age pension and widow’s pension for Māori were 25% lower than for Pākehā, for example. There were also cases where people could not rent property because they were Māori for that reason, and where banks and shops adopted policies of “No colored people (Māori) (※2)” as in these cases. Māori were prevented from using public toilets and were segregated from cinemas and pools. They were also refused alcohol service in bars, haircuts, and taxi rides, and it was not uncommon to see signs on city streets reading “No Māori allowed.”

Discrimination against Māori also occurred in language and culture. After the Treaty of Waitangi, the colonial government enacted education laws and organized a primary education system. At that time, those attending school were mainly Pākehā, and Māori children were marginalized from schooling. Although the Native Schools Act was enacted in 1867, its content was strongly assimilationist, imposing punishments on children who spoke Māori and promoting English-language education, thereby erasing minority identities. Because English was necessary for work and sport, Māori parents encouraged their children to learn English and adapt to a Western lifestyle. As the environment increasingly became one in which Māori children were educated only in English, there were concerns that the Māori language might disappear during the 20th century.

Beyond language, Māori culture was also affected by the colonial government. Traditional tattoos, a hallmark of culture that are symbols of rank, social status, authority, and prestige, carry different meanings depending on their design. However, because Christian missionaries preaching to Pākehā viewed them as “the devil’s art,” they lost support among young men.

A tattooed man carving Māori traditional art (Photo: Kathrin & Stefan Marks / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Revival of Māori rights and culture

From the 19th to the 20th century, the situation and changes in Britain had a major impact on New Zealand. For example, in the South African War and the two world wars, many soldiers left from New Zealand. During the wars, Māori units made significant contributions to Britain and were welcomed home as “heroes.” At the same time, New Zealand was gradually moving toward independence from Britain. In 1947, New Zealand adopted the Statute of Westminster, gaining legislative independence from the UK Parliament.

Through the wars, Māori developed a sense of identity. After the war, movements to revive Māori rights and culture gathered strength. The background included global events and trends: many countries in Asia and Africa gained independence from the postwar period through the 1960s; the U.S. civil rights movement; opposition to apartheid in South Africa; and the international trend toward restoring Indigenous rights. Initially focused on the return of wrongfully confiscated land and the promotion of te reo Māori, protests by activists, civic groups, and students, along with grassroots initiatives, spread in more diverse directions. Māori who moved to cities formed new Māori communities in their new homes to maintain culture, which helped trigger the revival movement. These Māori-led movements spurred the state to act, and the unfair treatment of Māori up to the prewar period gradually improved. Below, again divided into land, socio-economics, and language/culture, we look at the post–World War II situation.

Māori-language books on display in a library (Photo: Christchurch City Libraries / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

For many Māori, the most important issue was land. In 1920, Māori held 8% of New Zealand’s land, but by before World War II it had fallen to just 1%. From the 1970s, a surge of protests against land confiscations erupted, leading to the Treaty of Waitangi Act of 1975. The tribunal established under this law investigated Māori land claims and related matters. The tribunal’s powers were later expanded to consider claims arising after 1840. From the 1990s, claims for the return of wrongfully taken land and for compensation began. Marking its 45th anniversary in 2020, the tribunal has brought many land-related issues to light.

Turning to socio-economics, after World War II the New Zealand economy developed, supported by exports of high-priced agricultural products. Before the war, 75% of Māori lived in rural areas, but after the war they moved to cities in search of work, and by the 1960s 60% lived in urban centers. Higher wages improved Māori economic conditions, and people gained access to quality health care. Infant mortality and deaths from infectious diseases fell sharply, but deep-rooted socio-economic problems remain, and life expectancy still tends to be shorter than for Pākehā. Electoral reforms increased the number of Māori seats, and the Ministry of Māori Development (Te Puni Kōkiri) was established.

Finally, language and culture. In 1955, the Māori Education Committee was established, formally positioning Māori within education. Later, the activist group Ngā Tamatoa and Māori language organizations jointly submitted petitions to Parliament, prompting the launch of Māori-language education programs and broadcasts. The preschool-language program Kōhanga Reo and Māori-language primary schools emerged within communities, invigorating the movement to restore Māori culture. Consequently, the number of bilingual schools and Māori-medium schools increased. In 1987, Māori was recognized as an official language alongside English.

From the 1980s, Māori-language television and radio programs also began, a major development for Māori language rights. From the start in 1960 of television broadcasting in New Zealand and for 20 years thereafter, Māori people appeared on television mainly as entertainers such as singers, and there were no programs broadcast in Māori. Around the time Māori was recognized as an official language, however, programs introducing Māori education, culture, and customs appeared and played a major role in the language’s spread and recognition. In 2003, the government enacted a law to operate Māori-language public broadcasting with public funds, and today 2 television stations broadcast in Māori.

Filming set for a Māori television program (Photo: Michael Coghlan / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Other cultural aspects also saw revival. Traditional tattoos, once maligned by Christian missionaries, regained support from the 1970s, drawing greater interest from young people. In the 2000s, traditional Māori attire also began to be worn in formal settings.

Challenges ahead

As noted, the status and circumstances of Māori have gradually improved. However, Māori still face social and economic disadvantages compared with non-Māori. For example, large disparities remain in health and living conditions. Here too, we look at concrete examples in land, socio-economics, and language/culture.

First, disparities related to land. Efforts continue to return land to Māori, but it is hard to say the land issue has been resolved. Most issues related to land claims remain unsettled, and Māori, who account for 16.7% of the population, own only 5% of the land.

From a socio-economic perspective, although conditions for Māori are improving compared with the prewar period, economic disparities with non-Māori still exist. As of 2012, more than half of the country’s children living in poverty were Māori, and the unemployment rate has risen year by year. Due in part to structural discrimination and poverty, Māori parents have relatively lower incomes and therefore less funding to devote to their children’s education. Differences in parental income create educational disparities, lowering Māori educational attainment. After graduating, Māori children are more likely to find lower-paid jobs in manufacturing or wholesale, creating a negative cycle that makes later life more difficult.

Although the environment for Māori-language education in schools has improved, in the 2000s the number of Māori speakers declined, and the proportion of speakers is particularly low among the young. A certain number of non-Māori still push back against the use of te reo Māori, and broadcasters who continue to use it receive much abuse.

Furthermore, prejudice against Māori people and culture still remains. There have been insulting remarks toward Māori in Parliament, and a Māori MP who challenged the Western dress code by not wearing a tie was ordered to leave the chamber. Regarding the electoral system, a mechanism is currently in place that allocates a certain number of seats to Māori in single-member electorates, but some other parties have opposed it. As a kind of affirmative action (※3) to address such discrimination and disadvantages, one university’s medical school gives priority to admitting Māori students.

In 2020, Nanaia Mahuta became the first Māori woman to be appointed New Zealand’s foreign minister (Photo: Public Policy Forum / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

Outlook for the future

We have surveyed New Zealand’s history focusing on Māori land issues, socio-economics, and language/culture. Compared with many other Indigenous peoples around the world, Māori are socially protected in some respects, partly because they make up a relatively large share of the population and because the Treaty of Waitangi is a written agreement. Since the war, Māori culture has been increasingly recognized and accepted domestically, with new initiatives in politics, education, and the media. In recent years, the number of Asian residents has been growing in New Zealand, making ethnic identities ever more complex. At present, the petition for a name change mentioned at the outset has not reached a sufficient number of signatures and the change may not happen, but we sincerely hope the position of Māori will be further secured in the future.

※1 Because Māori ships at the time did not fly a national flag, there was a risk of seizure. For this reason, Māori chiefs chose their own flag, which became the national flag for ships departing New Zealand.

※2 For the record, GNV does not adopt classifications of human beings by “race.”

※3 Affirmative action refers to measures to remedy discrimination against groups historically disadvantaged by race, ethnicity, gender, and so on.

Writer: Koki Morita

Graphics: Aoi Yagi

マオリの権利や文化がこれほど浸透しているとは知らなかったのでとても興味深い記事でした!

歴史の流れでまとめられていてすごく読みやすかったです!!

包括的でとてもよくまとめられた記事だと思いました。ありがとうございます!

あまり知識のないまま観光でオークランドに行き、意外なほどマオリ文化の尊重を実感しました。博物館や街を訪ねて帰国、あらためて本稿を読んで理解が深まりました。ただ社会的経済的になかなか難しい状況なのも今後注目です。日本のアイヌ文化との交渉ややり方も考えざるを得ない。