“Human rights” are the rights that everyone is born with. Concrete examples include the right to life and freedom of expression, the right to an adequate standard of living such as food, clothing, and housing, the right to education, and the right to privacy. In recent years, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), international goals for building a sustainable world, have been grounded in the principle of respect for human rights. Nevertheless, human rights violations are still a matter of concern around the world today.

So, how well is the Japanese media reporting on this reality? Beyond the volume of reporting on human rights, are they able to cover countries and regions where the human rights situation is particularly serious? Furthermore, since “human rights” is a very broad concept with many types, how much of this spectrum does the media actually cover? To what extent do Japanese media make the world visible through the lens of “human rights,” and how well do they grasp the current situation and overall picture of human rights issues?

In this article, through an analysis of reporting by three major Japanese newspapers (Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun), I would like to consider the trends and characteristics of media coverage on human rights, and, in light of that, how the media should approach reporting on human rights.

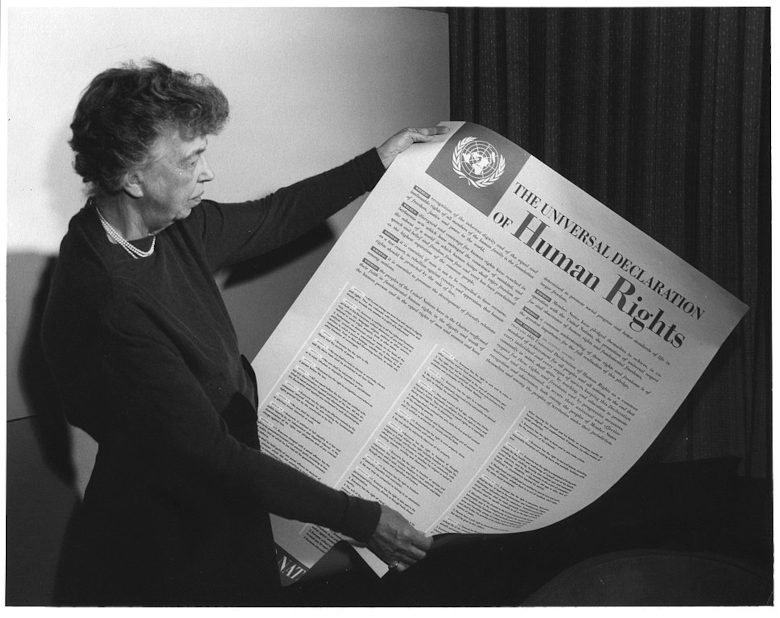

Former U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt looking at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights poster after its adoption (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum / Wikimedia Commons[CC BY 2.0 Deed])

目次

Background of the concept of “human rights”

Before beginning the analysis of human rights reporting, we first need to understand the background to how “human rights” came to be widely shared. Here, we will look at how “human rights” are defined internationally.

The most representative document that internationally defines “human rights” is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The UDHR was adopted at the United Nations General Assembly held in Paris, France in 1948. The declaration is grounded in reflection on the history of human rights violations committed during World War II, such as war crimes, persecution, and genocide. Although it is not legally binding, as a “common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations,” it can be regarded as a major achievement of modern society in that it proclaimed the protection of human rights internationally.

Subsequently, the treaties known as the International Covenants on Human Rights were adopted in 1966 and entered into force ten years later, in 1976. This gave legal protection to the content set out in the UDHR. The Covenants consist of two treaties: one guarantees social rights that require proactive state intervention, and the other guarantees liberty rights that, conversely, demand that the state not interfere in the realm of the individual.

In this way, the importance of human rights increased in the wake of the end of World War II, and their protection has advanced up to the present day.

A man holding a board that reads “Human Rights” (Photo: Wouter Engler / Wikimedia Commons[CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed])

Classification of “human rights”

As with the two International Covenants—one guaranteeing social rights and the other guaranteeing liberty rights—the term “human rights” encompasses a wide variety of types. Here, we consider how human rights can be classified. Focusing on the historical evolution in the understanding of human rights, we look at the classification proposed by Karel Vašák (※1), who divided human rights into three broad categories.

Vašák classifies human rights based on the element of “generation.” In other words, he noted that the characteristics of asserted human rights have changed over time and conceptualized them as three generations: “first generation,” “second generation,” and “third generation.”

The earliest asserted rights are classified as first-generation human rights and are considered negative rights. These rights are civil and political, including, for example, the right to life, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the right to a fair trial, and equality before the law. In other words, these rights demand that the state refrain from unnecessary interference with citizens.

The next generation of asserted rights are classified as second-generation human rights, focusing on social, economic, and cultural rights. These rights became necessary in response to the social and economic disparities that arose from rapid industrialization in the 19th century. Concrete examples include labor rights, rights related to social security, and the right to education. Moreover, the condition of “poverty,” into which people fall when they cannot even meet basic needs such as food, clothing, and housing, is also considered to belong to this category, as it involves violations of economic rights. In short, the rights asserted in this period are those guaranteed through active policy measures and intervention by the state, making them the opposite in nature to first-generation rights.

Thereafter, in contrast to the previously emphasized individual rights, as globalization advanced, rights that ought to be guaranteed to groups began to be asserted. These rights are addressed in international documents such as the Stockholm Declaration (1972) (※2) and the Rio Declaration (1992) (※3), adopted by the UN General Assembly concerning environmental management and development. Specific examples include self-determination, development, peacebuilding, the environment, humanitarianism, and the responsibility to protect (※4). These are rights that no longer fit within the confines of a single nation and require cooperation and solidarity with others—rights of a large scale. Therefore, compared to the previous two generations, they can be said to be comparatively vague in definition (※5).

Saudi Arabia’s representative speaking at the UN Human Rights Council (Photo: UN Geneva / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed])

Trends in international reporting on “human rights”: by country/region

Having outlined the definition and classification of human rights, let us move to the main topic. Around the world there are people whose human rights are being suppressed, and the kinds of harm they suffer vary. Faced with this reality, to what extent does the Japanese media capture the overall picture of human rights issues? In international reporting on human rights, where does the Japanese media place its emphasis? To explore this question, from here I analyze the volume and trends of one year (2023) of reporting related to human rights.

For this analysis, I used databases (※6) of three major Japanese newspapers (Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun). Among articles published in 2023, I targeted those that included the keyword “human rights” in the headline or body text and surveyed the reporting volume by country/region. Reporting volume is compared by the number of times a given country/region is mentioned in the relevant articles (※7). The number of articles in which the term “human rights” was mentioned was 152 for Asahi Shimbun, 115 for Mainichi Shimbun, and 346 for Yomiuri Shimbun. These figures show that references to human rights are not necessarily numerous.

The survey confirmed that various countries and regions were covered as articles, but the top 10 countries and regions with the highest total number of mentions across the three newspapers were as shown in the graph below.

The top three countries by number of mentions were China (152), the United States (128), and Russia (82), in that order. However, ranking high in this count does not necessarily mean that the country’s human rights situation is being criticized. Indeed, for China there were many articles on domestic suppression of freedom of expression and on human rights oppression in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and for Russia, articles continue to cover its invasion of Ukraine that began in 2022. For the United States, however, there was a tendency for more articles to address U.S. moves in diplomacy with other countries rather than domestic human rights issues. Regarding South Korea, articles were found on historically contentious human rights issues between Japan and South Korea such as the wartime labor issue and the “comfort women” issue. There were also articles covering “values diplomacy,” foreign policy that seeks to share policies related to democracy, the rule of law, and respect for fundamental human rights with other countries. Thus, it is evident that Japanese media do not only report on human rights violations and allegations thereof, but also emphasize actions perceived as easing human rights problems.

However, what deserves attention here is that there is a disparity in reporting volume among countries and regions where human rights violations are criticized. In this survey, Ukraine (under continued invasion by Russia), Iran (where the compulsory wearing of hijab for women is criticized), Israel (continuing incursions into Palestine), Myanmar (facing political repression and armed conflict), and North Korea (where government oppression of citizens is criticized) ranked high in reporting volume. Then how far does media attention extend to countries and regions that are being criticized for human rights issues?

There are other countries and regions showing relatively low scores on an indicator of how much civil liberties are guaranteed (※8). For example, Afghanistan, where human rights oppression under the Taliban regime is criticized, and countries with ongoing dictatorships such as Egypt, Eritrea, Turkmenistan, and Belarus. From these data, we can point to a contradiction with the results of the reporting-volume analysis. For instance, while both Iran and Saudi Arabia are in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia shows a lower score than Iran on the indicator. Yet the number of articles mentioning human rights in relation to Iran (44) exceeded those for Saudi Arabia (22).

Moreover, attention should also be paid to countries and regions where human rights are threatened in the form of “poverty.” According to an indicator of national poverty rates (※9), most of the countries with high rates are in Sub-Saharan Africa; however, for example, the Central African Republic and Eswatini—both among them—were mentioned only twice and once respectively, and South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo were not mentioned at all. This shows that these issues are scarcely reported as human rights problems, and again reveals a significant disparity in reporting among countries and regions with human rights issues.

Trends in international reporting on “human rights”: by type of rights

Next, using the same set of articles as in the country/region analysis, I classified each article according to which of Vašák’s three categories of human rights it fell into, and calculated the totals (※10). The results are shown in the graph below.

Summing across all three newspapers, articles related to first-generation human rights—which include civil and political rights—were most numerous at 308, followed by third-generation human rights—which include international and collective rights—at 246.5, and second-generation human rights—which include social, economic, and cultural rights—were fewest at 58.5. This pattern held for each newspaper: the order by count was “first generation,” “third generation,” then “second generation.” Themes seen among articles classified as first-generation rights included war-related harm, oppression of ethnic minorities, suppression of anti-government movements, and restrictions on freedom of the press. Themes among articles classified as second-generation rights included business and human rights (※11) and earthquake damage. Themes among articles classified as third-generation rights included ceasefire efforts, cooperation on security, oppression of sexual minorities, and issues related to migrants and refugees.

Focusing on first- versus second-generation rights, we see that the former—political rights—are reported more than the latter—economic rights. In other words, in international reporting, Japanese media can be interpreted as paying more attention to political human rights than to economic human rights.

Factors and background of reporting disparities

From this survey, two tendencies emerged: Japanese media generate disparities in reporting volume among countries and regions with human rights issues, and they place greater emphasis on political human rights than on economic human rights. Why do these tendencies arise? What background factors produce them?

The UN Human Rights Council (Photo: UN Geneva / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed])

First, as a factor behind the country/region bias in human rights reporting, it can be noted that Japanese media are disproportionately focused on great powers. However, not all great powers are central to their interest; rather, there is a tendency to prioritize coverage of great powers that are geographically and politically close to Japan. China, the United States, and Russia—at the top of the analysis—fit this pattern.

It can also be pointed out that Japanese media tend to emphasize the human rights issues of countries that are politically at odds with Japan or with which relations are not amicable. South Korea and North Korea are prime examples. Although smaller in scale than China, the U.S., and Russia, South Korea has the wartime labor issue and the “comfort women” issue with Japan, and North Korea has the abduction issue and missile-related issues with Japan—topics that naturally attract the attention of the Japanese government and media.

Furthermore, the depth of Japan’s relationship with the United States—another high-income country—also contributes to biases in country and regional coverage. The U.S. is the world’s most powerful country across politics, economics, military, and information dissemination. Not only the Japanese government but also Japanese media are strongly influenced by the U.S. Consequently, countries that are politically adversarial or in conflict with the U.S. tend to attract attention within the U.S. itself, and that influence leads Japanese media to cover them intensively as well.

Considering the earlier example of Iran and Saudi Arabia, Iran has no formal diplomatic relations with the U.S., whereas Saudi Arabia maintains friendly ties with the U.S. Despite Saudi Arabia being regarded as having a more serious human rights situation than Iran, it recorded fewer human-rights-related mentions than Iran. While Japan’s diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia are a factor, U.S. influence is one of the main reasons. Similarly, in Egypt, which, like Saudi Arabia, maintains friendly relations with the U.S., political repression is rampant, yet it was mentioned only 10 times in this survey—hardly a high reporting volume. This too exemplifies the strength of U.S. influence on Japan.

A demonstration in front of the UK Prime Minister’s Office opposing Egyptian President Sisi’s visit to London (Photo: Alisdare Hickson / Flickr[CC BY-SA 2.0 Deed])

A further factor behind underreporting of countries with serious human rights violations is that the very concept of “poverty” is not being framed as a human rights issue. Even prior to that, a past reporting analysis by GNV revealed a tendency for countries and regions with higher poverty rates to receive less coverage. On top of that, poverty and human rights are not being linked. Poverty is a chronic deprivation of the resources, capabilities, choices, security, and power necessary to enjoy an adequate standard of living, and this is unequivocally a human rights violation.

There is also the argument that high-income countries, for strategic reasons of maintaining their international advantage, downplay the existence of low-income, poverty-stricken countries. In this survey as well, none of the relevant articles framed poverty as a human rights issue. This fact can be said to be underpinned by the above factors.

Poverty is primarily a state in which economic human rights are being violated. The earlier analysis revealed the paucity of coverage of second-generation rights, which include economic rights. The reason appears to be that “poverty” is not being perceived as a human rights issue.

Nairobi, Kenya: densely packed housing (Photo: Rawpixel[CC0 1.0 Deed])

These tendencies align with the priorities and approaches to human rights in other high-income countries. For example, during the Cold War, the United States continued a political confrontation with the Soviet Union, and they also clashed over which types of human rights should be emphasized. From the perspective that human rights consist of social and economic rights, the Soviet Union of the Eastern bloc argued that economic rights are as important as, or even more important than, political rights. In contrast, the United States of the Western bloc, from the perspective that human rights consist of political rights, argued that political rights should be prioritized (※12). The former view is rooted in socialism, the latter in liberal democracy. In Japan, where American influence is strongly evident not only in government but also in the media, the approach to “human rights” similarly reflects the American tendency to de-emphasize economic human rights.

What is needed in human rights reporting

Let us recap the two biases in Japanese media’s human rights reporting that were revealed through this analysis. First is the disparity in reporting volume among countries and regions where human rights violations are pointed out; second is the disparity in reporting volume among categories of human rights. From the analysis and discussion so far, we can see that historical, political, and economic factors are intricately intertwined in the background.

Conversely, if these biases can be corrected and more balanced human rights reporting is achieved, Japanese media will be able to grasp the overall global human rights situation, and audiences will be able to understand human rights issues more accurately. The media have the function of providing information to the public and prompting the formation of public opinion. Balanced human rights reporting thus has the potential to enhance the human rights awareness of the audiences who receive it. “Human rights” are the rights that everyone is born with. For them to be naturally respected around the world, we should continue to scrutinize how the media report on human rights going forward.

※1 Karel Vašák: Czech and French scholar of international relations.

※2 Stockholm Declaration: A declaration agreed at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm, Sweden, from 5 to 16 June 1972. It summarizes the principles concerning the responsibilities that states bear to protect the environment.

※3 Rio Declaration: A declaration agreed at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from 3 to 14 June 1992. It reaffirmed the Stockholm Declaration and, in addition, advocated the need for sustainable development, indicating that cooperation between both high-income and low-income countries is indispensable.

※4 However, there are exceptions within the classification. For example, even among civil and political freedoms, the right to self-determination is treated as a third-generation human right, because the concept is closer to a group right. Also, although it transcends national borders, genocide and mass atrocities are treated as first-generation human rights, because they involve violations of individuals’ essential rights.

※5 There are theories that lend validity to Vašák’s classification. American political scientist Micheline Ishay, like Vašák, focused on the historical development of human rights and characterized them, from oldest to newest, as: the development of ideology; the establishment of institutions as international; and the assertion of the importance of human rights advocacy. American international relations scholar Jack Donnelly focused on the tendencies of emphasized rights in the three camps of the Cold War (Western bloc, Eastern bloc, and non-aligned countries) and characterized them respectively as civil and political rights; economic, social, and cultural rights; and the importance of solidarity and cooperation. Each of these threefold characterizations aligns with the features of Vašák’s three generations of human rights.

※6 The databases used for the survey were as follows. Asahi Shimbun: Asahi Cross Search; Mainichi Shimbun: Maisaku; Yomiuri Shimbun: Yomidas

※7 Details of the methodology are as follows. The survey period was from 1 January 2023 to 31 December 2023. Among all articles in the international section, those in which the search keyword “human rights” appeared in the headline or body were targeted. Variant spellings and character variants were allowed. However, articles that matched but did not in fact address content related to “human rights” were excluded. In this survey, mentions of each country/region were counted; therefore, if multiple countries/regions were mentioned in a single article, they were counted redundantly. (Example: if both Country A and Country B are mentioned in one article, count one for A and one for B.) As the focus was on countries/regions, institutions such as the United Nations and the European Union were excluded from the ranking, and Japan was also excluded, given the aim of analyzing international reporting.

※8 An indicator published by the V-Dem Institute, a research organization based at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. It expresses, on a scale from 0 to 1, the extent to which civil liberties are guaranteed. The closer to 1, the more civil liberties are guaranteed; the closer to 0, the more they are threatened. Data are for 2023.

※9 Here, poverty rate means the proportion of the domestic population living below the international poverty line (a living situation with only $2.15 per day to spend).

※10 The conditions and targets of the methodology were the same as for the country/region analysis. For calculation, when multiple human rights categories applied to a single article, I counted “1 ÷ (the number of applicable categories).” (Example: if two categories applied to one article, count 0.5 for each category.)

※11 Business and human rights: Initiatives to ensure that companies, in the course of doing business, do not commit human rights violations such as poor labor conditions or harassment.

※12 The reason why Western bloc countries prioritize political human rights can also be explained from a historical perspective. Western countries’ continued proactive engagement in external assistance in the modern era is said to be strongly influenced by the ideology of imperialism, which gained momentum in the 19th century. The ideology of imperialism carried a deep-seated sense of mission to promote the “civilizing” of other countries. While contemporary external assistance is of course also motivated by maintaining international order and humanitarian concerns, it can also be seen as driven, in part, by compulsions born of this ideology.

Writer: Ikumu Nakamura

Graphics: Virgil Hawkins

0 Comments