In international news coverage, the world is clearly divided into countries that are covered and those that are not, and the large disparities that exist between countries have also been revealed. But what, exactly, are the criteria by which countries are chosen as subjects of coverage? Researchers have cited a country’s “size” and the degree of its relationship with one’s own country as candidate factors.

So what is a large country, in other words a “major power”? This article uses populous countries as a starting point, then analyzes how economic power and military power relate to the amount of coverage in Japan. It also explores the relationship between Japan’s ties with other countries and the amount of coverage, based on trade volume and distance. Real GDP and military budgets are used as indicators to gauge economic and military power.

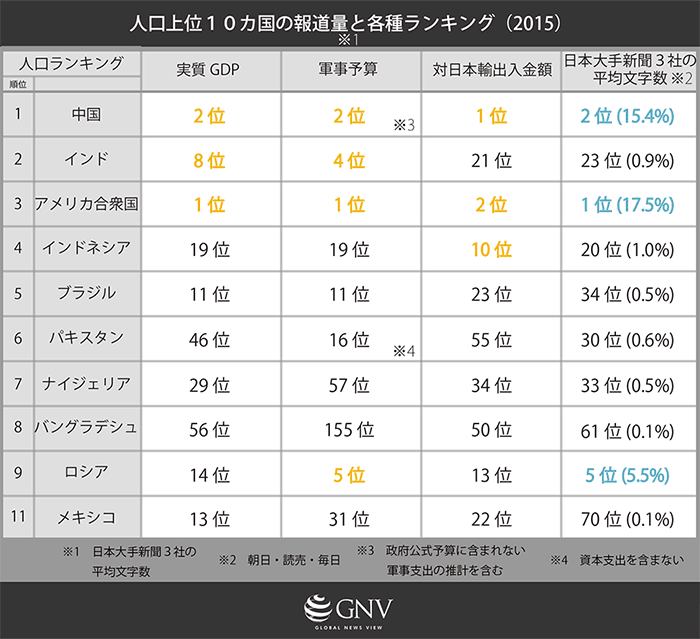

This table summarizes global rankings on the above indicators for the ten most populous countries in 2015. Below, each item is analyzed in detail.

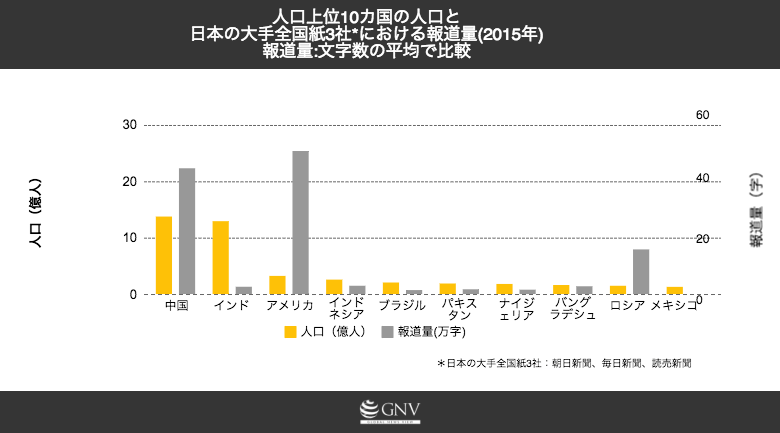

First, let’s look at the relationship between “population powers” and the amount of coverage. Lining up the world’s ten most populous countries in order and comparing their coverage volume for 2015 (one year) yields the following chart. Here, “amount of coverage” refers to the average, across Japan’s Asahi, Yomiuri, and Mainichi newspapers, of the total number of characters in all articles about the country.

As the chart shows, even among populous countries there are large differences in coverage. The United States, China, and Russia together account for just three countries yet make up 25.1%—a quarter—of the world’s population, and the average of their coverage across Japan’s three major papers amounts to 38.1% of Japan’s international news coverage. However, although the combined population of the remaining seven countries (excluding the United States, China, and Russia) surpasses those three and totals 32.6% of the world, their combined average amount of coverage is a mere 3.6% of Japan’s international news coverage. That 3.6% is roughly equal to the coverage of Syria alone, which ranked seventh by coverage volume. Given the overwhelming gap between population share and coverage, population size by itself does not appear to be a major factor determining how much coverage a country receives.

Next, we switch perspectives to economic power. Measured by real GDP, the populous United States (world No. 1 in real GDP) and China (No. 2) indeed rank among the top three economies and receive overwhelmingly high coverage. Germany (No. 4) and France (No. 6), which also have high real GDP, are likewise among the top ten countries by coverage (eighth and third, respectively). On the other hand, although they do not rank in the top ten by coverage, India and Brazil—both populous and members of the BRICS—rank in the top ten by real GDP (eighth and tenth, respectively). In fact, India’s real GDP is 1.5 times that of Russia, yet coverage of Russia is six times that of India.

Beyond economic power, another way to regard a country as a “major power” is military strength. Looking at military budgets, as with coverage, the United States (1st), China (2nd), and Russia (5th) have large military budgets. These three countries possess nuclear weapons and were victors in World War II. The country to note here, however, is India. India also ranks relatively high—fourth—in military spending and possesses nuclear weapons. Yet, as noted repeatedly, India’s coverage is strikingly small. When it comes to military power, though, what matters is not only raw budgets or whether a country has nuclear weapons, but also how that military power is perceived in relation to “one’s own country.” In Japan’s case, for example, it is understandable that China—sometimes perceived as a threat due to issues such as the Senkaku Islands territorial dispute—the United States—Japan’s most important partner under the Japan–U.S. security alliance—and Russia—long viewed as a threat by the United States—draw attention. One could say that India does not fit this perspective.

Summarizing the analyses of population, economic power, and military power, whether a country is covered in Japan cannot be explained solely by whether it is a “major power.” Still, as suggested in the discussion of military power, adding the relationship with one’s own country as a factor may offer some explanation, so to delve further we focus on trade volume with Japan. In the ranking of imports and exports with Japan, China is first and the United States second. As expected, these two countries top the list here as well, but the rest of the top ten includes three Southeast Asian countries—Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand—that receive relatively little coverage. Russia and France, which receive a lot of coverage, rank 13th and 19th, far below these three in trade with Japan. Even when bilateral ties are strong economically, they do not necessarily translate into coverage, and a clear correlation cannot be asserted.

Other elements can be considered as aspects of a country’s relationship with one’s own. Physical distance between countries is one. The paucity of coverage of Brazil—“large” in both population and economic power—may be due to its distance from Japan. However, we have already noted that even “major powers” close to Japan, such as Indonesia and India, tend not to be covered. Looking at cultural “distance”—how strongly countries share similar elements such as tradition and religion—coverage is high for countries like China and those on the Korean Peninsula. For “Asia” beyond these countries, a similar cultural closeness is not evident from the amount of coverage. Rather, factors such as a similar standard of living (individual-level affluence) to Japan may be more important for coverage. For example, although European countries are physically far and fall below Asia’s major powers in real GDP values and trade volume, their coverage is many times greater than that of Asia’s major powers excluding China. Perhaps there is an implicit recognition that advanced countries with similar individual-level affluence have higher news value.

As seen above, none of these criteria alone can be said to determine the amount of international coverage in Japan; rather, various factors interact in complex ways to shape Japan’s international news. As one example, let us analyze in more detail the volume and content of coverage about Russia. It is understandable that the United States and China, which generally ranked high on all the criteria examined here, receive extensive coverage. But why was Russia—whose rankings are not that high in economic power or trade with Japan—covered so much in 2015?

In 2015 coverage of Russia by the Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri newspapers, conflict-related articles accounted for 10%. The situation in Ukraine was particularly prominent, representing 10% of all articles about Russia. Behind this volume is concern that, as a Cold War–era major power, Russia’s confrontation with the United States is intensifying and heading toward a “new Cold War.” Japan also has the Northern Territories issue with Russia, giving it many reasons to attract attention compared with other countries. Even so, in 2015 the volume of coverage about Russia appears to have grown based on a variety of factors, such as the state of world affairs, the presence or absence of incidents, and whether issues with Japan were involved.

In any case, it seems that Japan’s current international news is skewed toward its own interests and particular events, leaving other regions—including other “major powers”—neglected. Even if the reasons for covering Russia are understandable, it is hard to fathom why “major powers” close to Japan, such as India and Indonesia, are not covered. The existence of major powers that go uncovered is a problem, but more broadly, disparities in coverage remain a major challenge in international news.

Writer: Sayaka Ninomiya

Graphics: Mai ishikawa

0 Comments