Among the topics often raised in discussions on how to address international issues is “Official Development Assistance,” commonly known as ODA (Official Development Assistance). ODA almost always comes up when debating responses to conflicts, disaster damage, or long-term development challenges such as poverty, health care, and education. Although it has taken root as “assistance” with a relatively favorable image—namely, support from high-income countries to low-income countries—the reality is that it carries a variety of problems. This article examines the realities and issues of ODA.

Relief supplies delivered from the EU to flood-affected Pakistan (EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 DEED ])

目次

The history of international assistance

First, to analyze modern international assistance, we will outline how international assistance has developed over time.

Assistance has been provided in many forms since ancient times. Religious groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), foundations, and wealthy individuals have long histories of supporting others for various reasons. Among these actors, states have been primary players, providing “assistance” to other countries in different ways throughout history. Much of this “assistance” has been carried out strategically—for example, to secure national security through aid to allies, to gain advantages in trade, or to garner diplomatic support. The modern state-led international aid system took shape during the World War II era.

In 1944, as World War II was drawing to a close, the Bretton Woods Conference conceived a system to support the international economy centered on the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As part of that, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) was established as an early institution within the World Bank Group to finance post-war reconstruction, initially focusing on Europe’s recovery. However, since the IBRD mainly provides loans, it differs somewhat from aid in the literal sense.

In 1948, the United States formulated the Marshall Plan to support the reconstruction of European nations. This stance was informed by U.S. considerations vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. Although Eastern bloc countries, including the Soviet Union, were initially eligible for the Marshall Plan, the Soviet Union rejected it as part of U.S. imperialism. This ultimately helped solidify the East–West Cold War structure. Conversely, the Soviet Union formed the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) in 1949 to strengthen cohesion among Eastern bloc countries, initially supporting European states within the bloc. At this time, non-European countries—such as those in Asia and Africa, except some like Japan—rarely received aid, which some believe had a major impact on subsequent disparities.

Scene from a DAC High-Level Meeting (OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED ])

In 1948, the Marshall Plan triggered the establishment of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC). Building on the OEEC, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was launched in 1961 with the addition of the United States and Canada, transforming it from a Europe-centric institution into a more global one. The OECD created the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) in 1960, which engages in coordinating ODA and setting rules. ODA is defined by the DAC as “government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries.” In 1969, it designated ODA as the “gold standard,” meaning the core of external assistance, and it remains the primary source of development aid today.

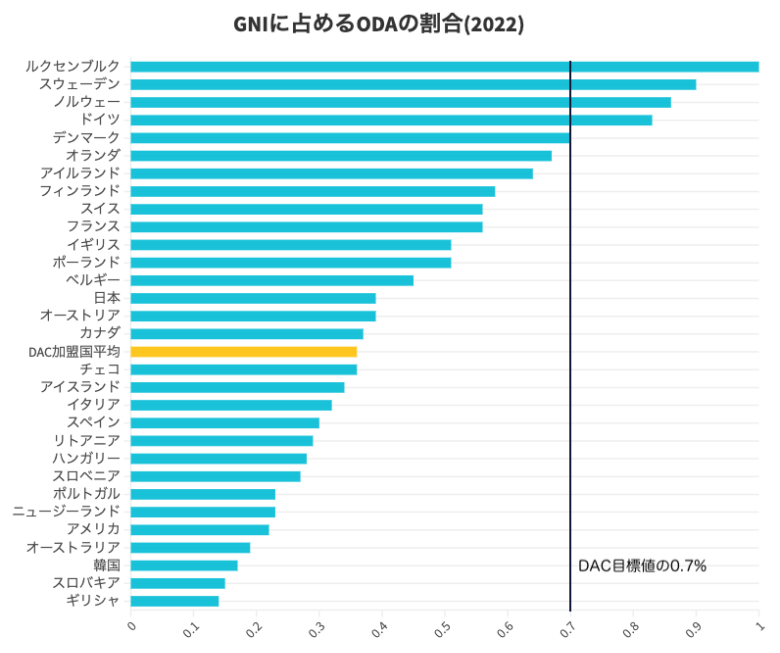

At the International Development Strategy conference in 1970, reflecting expert recommendations, DAC member countries set a quantitative target for ODA contributions of 0.7% of their own Gross National Income (GNI) to provide the financing needed for developing countries (※1) to achieve appropriate development. This was also adopted as a United Nations General Assembly resolution and remains a benchmark today.

Insufficiency and bias in ODA

Is the ODA system functioning properly today? The answer must be NO. First, the absolute volume of aid is woefully insufficient. According to 2022 data, only 5 countries—Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Norway, and Sweden—out of the 30 DAC participants met the ODA target of 0.7% of GNI. This is not because 2022 was exceptionally low; the previous year was the same, and earlier years were at similar levels. Even the United States, which ranks first in total aid volume, accounts for only 0.22% of GNI. The average across all 30 countries is 0.36%, far below the 0.7% target. Moreover, as detailed later, this includes unusually large, irregular items such as support for Ukraine; in typical years, it is often lower.

Created based on OECD data

It’s not just that the volume is small; there is also the question of whether funds are allocated appropriately relative to global needs—i.e., whether there is a mismatch between the need for and supply of assistance. In reality, there are significant biases. Here are some prominent examples (※2).

2003 saw the start of the Iraq War following the U.S. invasion, and Iraq received approximately 3.46 billion USD in assistance from around the world. By comparison, the second-largest recipient, Ethiopia, received about 490 million USD, and third-place Afghanistan about 450 million USD. It should be noted that other major conflicts were also underway that year. For example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, by November 2002, an estimated 3.3 million people had lost their lives in the conflict—reportedly the highest death toll since World War II—with the majority due to disease and hunger, according to reports. Nevertheless, the DRC ranked seventh in aid received, at 180 million USD, underscoring just how skewed assistance was.

In a recent example, the total emergency assistance to Ukraine in 2022 amounted to approximately 4.39 billion USD. Afghanistan ranked second with about 3.88 billion USD, and Yemen third with about 2.75 billion USD. While death tolls alone are not a sufficient basis for comparison, as of June 2022, deaths from conflict in Myanmar were higher than in Ukraine. Yet Myanmar ranked 23rd in 2022 aid with 430 million USD—about one-tenth of the aid to the Ukrainian government. In response to the conspicuous emphasis on supporting Ukraine, African countries have repeatedly criticized donor countries at international forums for “double standards.”

Shelters provided to displaced Iraqis with support from the United Kingdom (DFID – UK Department for International Development / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

Similar trends can be seen in long-term development assistance. Data show that, proportionally, more aid goes to countries with moderate levels of poverty than to the poorest countries—where needs should be persistently highest—when it comes to long-term development assistance data. For example, in 2021, only 13% of Germany’s aid went to the least developed countries. This suggests that aid is being used strategically—for instance, to obtain better terms in investment and trade or to secure political support.

From another angle, there is also a bias in how funds are used. Since around 2000, year after year a large share of humanitarian aid has been allocated to the World Food Programme (WFP), and in 2022 about 34% of all emergency aid went to the WFP. The WFP works to save people from hunger and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020 for its achievements. However, it has also been criticized in the past for effectively supporting the U.S. economy by purchasing American agricultural products in the course of delivering aid. While food-related issues are indeed a major concern among many pressing global problems, such a large bias suggests potential arbitrariness in budget allocation.

Thus, amid insufficient aid volumes, there are stark disparities in how assistance is distributed.

WFP relief supplies for storm damage in Haiti (United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

Aid that never reaches the field and stays in high-income countries

What other problems exist? Countries are striving to move their ODA closer to the target of 0.7% of GNI, but one issue is that funds are not spent in low-income countries but instead in high-income countries—often paid to the donor’s own country. Between 2011 and 2021, the share of aid directly received by countries in the Global South (※3) averaged only 40% of total ODA. This cannot be considered healthy assistance. How does this happen? One rationale is “refugee support.” There are cases where donors allocate aid to support refugees they have accepted domestically—by funding their own refugee-support groups or other high-income countries’ refugee agencies. For example, in the United Kingdom in 2022, about one-third of total ODA was spent on supporting refugees at home. This problem became particularly pronounced with the outflow of refugees from the Russia–Ukraine conflict in recent years.

Another example is when implementing agencies count budgets for domestic training and facility operations as ODA. In Japan, for instance, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) includes training costs for trainees accepted in Japan and parts of the Ministry of Education’s programs for accepting international students as ODA expenditures. The United Kingdom similarly counts training and acceptance of international students as ODA. While these are not entirely unrelated to supporting low-income countries, counting such costs as ODA means that a large share of ODA is spent domestically and recycled into the donor’s own economy.

There are other reasons funds remain in high-income countries—health being one. This was an existing issue, but it became particularly pronounced with the spread of the coronavirus. The outbreak beginning in 2019 led to large expenditures, and as a result, total international ODA reached an all-time high.

However, even if the nominal volume reached a record high, it is hard to see this as genuine international assistance. Behind the figures, there were cases where high-income countries “disposed of” surplus vaccines they had over-purchased from pharmaceutical companies as ODA as those supplies neared expiration, according to reports. Counting vaccines as ODA is now permitted by DAC rules. Yet close-to-expiry doses were delivered to Africa, sometimes making it impossible to use them in time and forcing disposal there. Recipient countries often refused “ODA” vaccines due to expiration concerns. There are also reports that ODA was counted at amounts higher than the actual prices high-income countries paid for the vaccines. As GNV has repeatedly pointed out, this suggests that specific pharmaceutical companies and entrepreneurs engaged in R&D for vaccines and test kits likely profited the most.

COVID-19 vaccines delivered to Ethiopia from the German government (UNICEF Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

Aid that reaches the field but is ineffective, or even counterproductive

The previous section pointed out the problem of aid not reaching the field at all. But is it enough if it does reach? There are cases where aid that reaches the field is ineffective—or even produces the opposite of the intended effect. First, here are examples of weak effectiveness.

One is what’s called tied aid, which simply means the donor specifies the companies or institutions that will implement the aid project—often those from the donor country itself. For example, a donor might fund infrastructure development in a recipient country and then designate a donor-country company to handle the construction.

While the infrastructure remains in the recipient country, the cost can become extremely high because it must be carried out at high-income-country price levels. Moreover, part of the ODA flows back to companies and the economy of the donor country. If the ODA takes the form of loans, the recipient is saddled with repaying debt for a very expensive project. Because this type of aid has been criticized, there has been a public move to eliminate it. However, even when officially reported as untied, many cases still effectively look like tied aid in practice. For example, the Canadian government reported that 100% of its 2017 aid was untied, yet reports show that, on a monetary basis, 95% of the aid was paid to Canadian companies.

Japan is a leading country in expanding tied aid and, unlike many others that disclose partnership details in technical cooperation, it has maintained a stance of not disclosing—indicating a lack of transparency. This suggests that aid is still, albeit unofficially, being provided in tied form. Such tied aid is highly inefficient for recipient countries in terms of cost. Among companies and organizations that undertake such ODA projects in Japan, there are even slang terms like “ODA money” and “ODA business.”

Tying also frequently occurs in the purchase of food and goods. When aid is sent to distant countries with the condition that purchases be made from the donor’s own firms, transport costs soar. In fact, about 65% of the U.S. foreign food aid budget is recorded as “transportation,” implying extra costs that would not arise with local or nearby purchases. Beyond cost inefficiency, local procurement helps stimulate the surrounding economy and can be more effective. Moreover, maritime shipping emissions can contribute to global warming, compounding negative effects.

A bridge built in Sri Lanka with support from JICA (Mahinda Rajapaksa / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED ])

Problems have also been noted on the recipient government side. Although not a very large share overall, there are reports of corruption and fraud in the ODA process—cases where aid does reach the field but is not used appropriately.

There are also situations where the genuine will of the people who need support diverges from the will of the recipient government that decides the form and scale of aid, and the government’s will prevails. In such cases, even if aid is provided, it may fail to deliver real value and be less effective. In other words, the recipient country’s leadership makes requests to the donor, and the donor responds—yet the resulting project serves the leader’s political interests and does not match the population’s actual needs. One example is China’s aid for stadium construction. These are not everyday necessities but numerous stadiums built in low-income countries. Although China has officially proposed “no strings attached,” it has sought steps such as severing diplomatic relations with Taiwan, revealing pursuit of its own national interests.

There are also instances where aid brings counterproductive effects to recipient countries. For example, the ProSavana project in Mozambique, agreed and led by the Japanese and Brazilian governments in 2009 as part of ODA. Targeting the Nacala Corridor in northern Mozambique, it aimed to develop tropical savannah agriculture to reduce poverty among small-scale farmers, ensure food security, and promote economic development through private investment. However, the project proceeded while providing only limited information to local people, keeping much under wraps. Although it was presented as triangular cooperation among Japan, Brazil, and Mozambique, in reality it was the outcome of bilateral diplomacy between Japan and Brazil, with hidden motives such as addressing unemployment in Brazil and securing cheap food supplies for both countries, with Mozambique merely selected afterward as a convenient target. As a result, smallholder farmers in Mozambique fiercely criticized it as the seizure of their land. Ultimately, after opposition movements, the project stalled midway.

Signing ceremony for a strategic partnership between the United States and Thailand (USAID Asia / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED ])

Stepping a bit away from state-led aid, there are also cases where NGOs donating used clothing to African countries ended up collapsing the recipient’s textile industry. Donations and cheap resale of used clothes from major powers led to job losses among domestic textile workers, resulting in unemployment and poverty. When recipient countries attempted to regulate the inflow of used clothing, there were even cases of pressure from the U.S. government. In this way, simplistic aid can sometimes worsen, not improve, domestic conditions.

Is ODA a complete solution?

We have surveyed several problems with ODA. Would a large increase in ODA, better need-based allocation, and more appropriate, efficient delivery to the field achieve the world that foreign aid aims for? No. Emergency aid in particular is expected to serve only as a temporary bandage. Conversely, it does not directly resolve fundamental issues such as poverty. While there is long-term development aid that helps address root problems, reliance on aid can grow into dependence, making aid itself unsustainable.

Causes of poverty vary by country, but a major factor is the unfair global trading system that works to the advantage of high-income countries and their corporations. In other words, without solving issues GNV has long pointed out—such as unfair trade and illicit financial flows using tax havens—it is difficult to tackle root problems. These two factors have historically contributed to widening inequality. There are also disparities that become starkly evident during global crises such as COVID-19. Assistance, as discussed here, structurally involves high-income countries “bestowing” aid on low-income countries, but the issues in this section amount to a kind of exploitation of the latter by the former. Unless we seriously address these distorted structural problems, the role that ODA can play will remain highly limited. The path to resolving these deep-rooted issues is long.

※1 As a rule, GNV does not use terms like developing/advanced countries, instead using low-income/high-income countries, but in the context of ODA the official term is “developing countries,” so we follow that usage here.

※2 Here we refer to data from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS). Note that these figures are only for aid channelled through the UN system and do not include all bilateral assistance, etc. The bias discussed above refers to concentration of aid on specific countries. Also, the data here cover emergency assistance only, so long-term aid may not be included in the amounts.

※3 While Global South is a polysemous term, we use it here as it appears in the OECD report.

Writer: Yusui Sugita

Graphic: Yusui Sugita

0 Comments