In March 2023, it was the 20th anniversary of the start of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. U.S. President George Walker Bush launched the attack on Iraq on the false pretext that Saddam Hussein’s regime possessed weapons of mass destruction. The U.S.-led multinational forces toppled the Hussein regime.

In 2011 U.S. forces withdrew and the end of the war was declared. Even afterward, Iraq, whose political system and infrastructure had been left dysfunctional by the war, remained unstable, and the rise of the Islamic State (IS) brought large-scale armed conflict again. As of 2023, Iraq is said to be the most stable it has been since 2003, but at the same time it still faces many localized conflicts and challenges in politics and the economy. What is the state of Iraq today? Let’s look at Iraq now from the perspectives of history, politics, society, and external relations.

Baghdad, the capital of Iraq (Photo: MohammadHuzam / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED])

目次

History of Iraq

Iraq is a country in the Middle East with an area of about 438,000 square kilometers and a population of about 39.65 million. People with diverse cultural, linguistic, and ethnic backgrounds live there. Roughly 60% of the population are Shiite Arab Muslims, about 20% are Sunni Arab Muslims, about 20% are Kurds, and others include people who identify as Turkmens and Assyrians. Both Arabic and Kurdish are official languages, and the population includes not only Muslims but also Christians and others.

In ancient times, the Mesopotamian civilization, considered one of the world’s oldest, emerged in this region. In the 8th century, Baghdad—today’s capital of Iraq—became the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate and thereafter flourished as Iraq’s historic city. From the 16th century onward it became part of the Ottoman Empire, and after World War I it became a British mandate. Iraq became independent in 1932 as the Kingdom of Iraq, but the monarchy collapsed in the 1958 revolution and it became the Republic of Iraq. In 1968, General Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr established a Ba’athist regime. The Ba’ath Party is a pan-Arabist (※1) party advocating the creation of an Arab socialist state, active mainly in Syria and Iraq.

After Bakr resigned, in 1979 Saddam Hussein became president. Under the Bakr regime, he served as secretary and deputy chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council and, alongside the president, effectively ruled Iraq. After Bakr’s resignation, he became president and also served as chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council and prime minister. Domestically, he suppressed opposition with a vast secret police apparatus, and externally he took an aggressive stance. In 1980, against the backdrop of tensions with post-revolution Iran, he launched an invasion of Iran; this Iran–Iraq War remained in a stalemate until 1988.

In 1990, amid disputes over control of oil resources, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Because Iraq did not comply with UN Security Council resolutions demanding withdrawal, in 1991 a U.S.-led multinational force used military force against Iraq, escalating into the Gulf War. Following Iraq’s defeat, strict economic sanctions were imposed mainly by the U.S. and the U.K., resulting in a humanitarian crisis in which many people, including over 500,000 children, died. Iraq’s crushing defeat triggered uprisings by Shiites in the south and Kurds in the north, but Saddam violently suppressed them. Thousands became refugees and over 1 million Kurds fled to surrounding areas, and thousands were tortured and killed. After the Gulf War, a Kurdish safe haven was established in northern Iraq by the multinational force, through which the Kurds gained de facto autonomy. This later formed the basis of the Kurdistan Region in Iraq.

After the September 11 attacks in the U.S. in 2001, President Bush claimed Iraq was in some way involved and was developing and possessing weapons of mass destruction, and in 2003 a U.S.- and U.K.-led coalition invaded Iraq. It is now known that the justifications for the invasion were false. Saddam was captured by U.S. forces, the one-party dictatorship collapsed, and a U.S.-led occupation of Iraq began. In 2004 the occupation authorities established the Iraqi Interim Government. Saddam was later found guilty of “crimes against humanity” in Iraq in 2006 and was executed.

Saddam Hussein (Photo: Matt Buck / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

During the occupation, U.S. decisions resulted in the purge of Ba’ath Party members from public office. Under the long-time Ba’athist one-party dictatorship, all key personnel were party members. The purge and the dissolution of the security forces created a political and security vacuum, spurred violence, and worsened public order. Resistance and opposition to the occupation by U.S. troops and private military companies continued, and torture under the occupation and massacres by private military contractors occurred. Sectarian power struggles that had been suppressed under the dictatorship intensified with the dismantling of the security apparatus, and from around 2006 to 2008 Shiite–Sunni sectarian conflict descended into open warfare. Since 2003, Shiite militias backed by Iran have proliferated.

In 2011, U.S. forces withdrew from Iraq, ending the occupation. In 2012, the arrest of several Sunni officials triggered protest demonstrations against the Shiite-led government. When security forces moved to suppress them, sectarian power struggles intensified again in 2013. The number of civilian deaths in 2013 was 7,157, more than double the 3,238 the year before. Seizing on the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the chaos of armed conflict, the Islamic State (IS)—formed by Sunni factions and former Ba’athists that had opposed the occupation and fought U.S. forces—began to rise in Iraq and Syria. To discredit and weaken the central government, they attacked security forces and carried out frequent terrorist attacks targeting Shiites. IS also attacked Sunni areas and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), seizing a vast swath of territory from northern Syria to central Iraq and reaching its peak in terms of area controlled by 2015. As U.S.- and Russian-led military operations against IS intensified, IS’s territory and strength declined. In 2017, Iraqi security forces, Shiite-led militias, and the KRG’s Peshmerga all stepped up their offensives against IS, and in the same year IS lost almost all of its territory in Iraq.

Political situation

From here, we look at Iraq’s current politics. There are no political parties representing the entire country; parties are broadly divided into Shiite parties whose base is in the south among Shiite communities, Sunni parties with a base in central Sunni communities, and Kurdish parties based in the Kurdistan Region in the north. In each region, multiple parties from factions based there compete, resulting in coalition governments. Under Iraq’s electoral system, all major ethnic and sectarian parties participate in government, and there is no formal opposition.

This electoral system was introduced in 2003 by the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) led by U.S. forces to rebuild Iraq’s government, and is called Muhasasa Ta’ifiya. Originally proposed in 1992 by groups opposed to Ba’athist rule, it allocates offices by the ethnic and sectarian identity of legislators. The U.S. used this system to establish the Iraqi Governing Council in 2003, and it has been used since the 2005 parliamentary elections to the present. By linking ethnic and sectarian identity to politics, this system has deepened sectarian divisions in Iraqi society. It is also believed to have fostered a lack of cohesion among political elites, leading to corruption and inefficiency driven by personal gain, and to have encouraged foreign interference.

In 2004, authority was transferred from the CPA to the Iraqi Interim Government, and in 2006 the first democratically elected postwar government took office, with Shiite politician Nouri al-Maliki serving two consecutive terms as prime minister. In 2008, the Iraqi parliament approved a security agreement with the U.S., and in 2011 the U.S. withdrawal was completed. In 2014, Haider al-Abadi, from a Shiite party, became prime minister and formed a government that included Sunnis and Kurds. In 2018, Adil Abdul-Mahdi took office. Since 2003, each change of government has promised political and economic reforms, but effective reforms have not been implemented, and public dissatisfaction with corruption, high unemployment, inadequate public services, and U.S. and Iranian interference has been mounting.

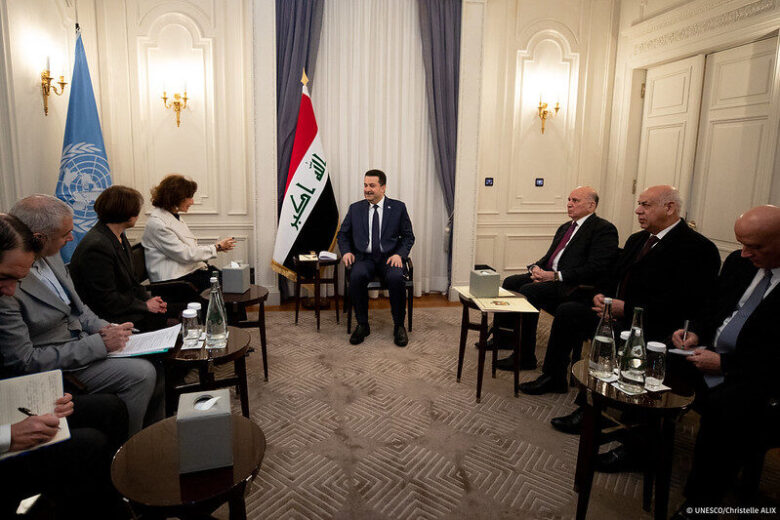

Prime Minister Mohammed al-Sudani (Photo: UNESCO Headquarters Paris / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED] )

Public dissatisfaction boiled over in October 2019, when protests calling for electoral reform broke out in Baghdad and southern Iraq and spread nationwide. Clashes between demonstrators and security forces left about 600 protesters dead and more than 20,000 injured within six months. This became Iraq’s largest protest movement since 2003, and then–Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi resigned. In 2020, a new government led by Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi was formed, but no concrete reforms followed. As recently as the year from 2021, a corruption scandal saw about US$2.5 billion in public funds siphoned to businessmen through bureaucrats.

Apart from the electoral system, there is also a custom that the prime minister is nominated by Shiite parties. In post-election coalition talks, this custom fuels competition among Shiite parties over the right to nominate the prime minister. For example, in 2021 the Shiite alliance led by Muqtada al-Sadr won the most seats in the parliamentary elections. Sadr opposes Iranian influence in Iraq and is distinct from other Shiite leaders with deep ties to Iran. When he failed to form a government due to relations with other Shiite parties, in 2022 Sadr’s lawmakers resigned en masse, followed by Sadr himself withdrawing from politics. Iraq went nearly a year from 2021 without a prime minister, with protests by Sadr’s supporters and confusion due to the political vacuum.

Then in October 2022, the appointment of Mohammed al-Sudani as prime minister ended more than a year of political deadlock. Compared with previous governments, Sudani is said to be taking more effective steps to improve public services. On the other hand, the Muhasasa Ta’ifiya electoral system has not been reformed, and fundamental solutions to corruption and poor public services have yet to advance.

Kurdistan Region

People who identify as Kurds make up about 20% of Iraq’s population. An estimated around 30 million Kurds live across regions spanning the borders of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Armenia, making them the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East. However, they are minorities in each country, have never had a lasting state, and have been subject to discrimination and repression. Iraq is the only country where Kurds have their own governing body, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

First, a brief history of the KRG. Since the 1960s, the north has seen intermittent Kurdish insurgency. After the Gulf War in 1991, a U.S.- and U.K.-led coalition unilaterally established a no-fly zone in the north under the pretext of protecting Kurds, and Iraqi troops withdrew from the area. As a result, Kurdish leaders and their security force, the Peshmerga, came to exercise effective control over northern Iraq. After the 2003 U.S. invasion, a new constitution was enacted in 2005 after negotiations between the CPA and the Iraqi Governing Council. The new constitution introduced federalism and recognized Kurdish autonomy in the Kurdistan Region. In 2006, the KRG was established.

Within Iraq, the Kurdistan Region holds the status of a region constituting the Iraqi federation. The KRG’s main parties are the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), and it governs as a coalition including other parties. Since 2003, the KRG has largely avoided the turmoil afflicting the rest of Iraq, using revenues from oil exports to rebuild infrastructure, build institutions, and accept displaced people, thereby achieving economic growth and parliamentary democracy. Its own security force, the Peshmerga, maintains security and order in the north independently of the Iraqi army. In this sense too, the Kurdistan Region is subject to very little de facto governance by the central government and is, in practice, close to a state in its functioning.

The KRG faces several challenges, starting with its relationship with Baghdad. In 2012, there were clashes between security forces of both sides in disputed territories claimed by both the KRG and the central government. In 2014, the shared threat of IS temporarily improved relations, but after IS weakened, in 2017 the KRG authorities held a referendum on independence in areas under KRG control, which passed overwhelmingly. The central government, strongly opposed to the vote, advanced into Kurdish-held areas in the north, leading to clashes between Iraqi forces and Kurdish fighters. Since 2018, negotiations have reduced tensions, and both sides have been working to build a stronger cooperative framework.

Kurdish rally (Photo: Levi Clancy / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED])

Relations with countries that view Kurdish groups as adversaries, such as Turkey and Iran, are also a challenge. In Turkey, since the founding of the republic, rising nationalism has led to oppressive policies toward non-Turkish Kurds. These countries want to prevent their own Kurdish populations from seeking independence and rebelling, inspired by Iraq’s Kurdistan Region. With that aim, Iran and Turkey have carried out attacks inside Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, and Turkey has invaded and occupies parts of it.

There are also internal challenges. In the mid-1990s, conflict broke out between the two main Kurdish parties, the KDP and PUK, after which the Kurdistan Region was effectively divided east–west and partitioned rule by the two parties persisted. As of 2023, tensions between the KDP and PUK have deepened, and the region’s politics are in their most critical state since the Kurdish infighting of the mid-1990s.

Economy and society

Because oil resources support most of Iraq’s economy, the entire economy is heavily affected by global oil demand. Over the past 10 years, oil has accounted for over 99% of exports and 85% of government revenue, making Iraq one of the most oil-dependent countries in the world. The budget depends on crude prices: when they rise, revenue increases; when they fall, finances shrink. For example, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic slowed the global economy, oil demand plunged, and crude prices crashed. As a result, the government was unable to fund public services and even struggled to pay civil servant salaries and pensions on time.

After the 2003 war and U.S. occupation, Western companies that had previously been excluded from Iraq’s oil sector resumed production in the country. Since then, much of the wealth generated by oil has flowed out to foreign firms extracting it. Funds have also leaked due to domestic political corruption. Although oil prices later recovered, without structural reforms to develop non-oil sectors and overcome oil dependence, Iraq’s economy will continue to be swayed by crude price fluctuations.

Iraq’s oil platform (Photo: Mass Communication 2nd Class Nathan Schaeffer / Wikimedia Commons [PDM 1.0 DEED] )

An oil-dependent economy has failed to create enough jobs for a rapidly growing labor force. Iraq’s population is projected to more than double between 2015 and 2050, the highest estimated growth rate in the Middle East and North Africa over this period. The capital-intensive oil sector has bloated the public sector, stunted private-sector growth, and led to job shortages. In fact, about 40% of Iraq’s workforce is employed in the public sector. To address public demands for jobs, governments have temporarily eased discontent by pledging more public-sector hiring, rather than implementing structural reforms to grow the private sector. Youth unemployment is particularly high: as of 2022, unemployment among those aged 15 to 24 was 34.6%.

On top of economic problems, Iraq faces severe environmental challenges. The country is said to be experiencing its worst water scarcity in 100 years, affecting 7 million people through reduced access to water. There are multiple causes. Externally, Iraq is highly vulnerable to climate change. According to the UN Environment Programme, Iraq is among the world’s five most climate-affected countries. About 92% of Iraq’s land is at risk of desertification, and temperatures are rising at roughly seven times the global average. In 2022, an estimated 98% of Iraqi households lived in areas of precipitation deficit.

In addition to climate change, domestic factors such as poor water management and slow infrastructure development have exacerbated water shortages and pollution. Conditions are especially dire in Basra, a southern port city, where in 2018 118,000 people were hospitalized with symptoms from waterborne diseases and contamination. To address the crisis, the government has sought to improve its share of upstream water with Iran and Turkey and participated in the UN 2023 Water Conference aimed at solving the global water crisis. However, critics say these efforts focus on external factors like other countries and climate change while neglecting domestic issues like water infrastructure and reforming inefficient irrigation systems at home.

People walking on parched land (Photo: UNDP Climate / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED])

Beyond climate change, weak infrastructure, and governance, a major driver of water scarcity and pollution is the extraction and contamination of water resources by Western oil companies. Oil production uses vast amounts of water, competing with water needed for agriculture and consumption; water is being diverted to Western oil plants before reaching the major rivers that are the primary sources for southern Iraq. Gas flaring during crude production releases carbon dioxide and toxic gases, causing severe environmental pollution and health damage in the region.

Lastly, consider migration and displacement. Iraq is home to minorities. Since the fall of Saddam’s regime in 2003 and the intensification of ethnic and sectarian conflict, many non-Muslim Iraqi minorities have been forced to flee. When IS rose in 2014, the Yazidis were targeted, and hundreds of thousands of Yazidis fled. The return of those who fled IS attacks has still not progressed. As of early 2023, over 1 million Iraqis remain displaced.

Foreign relations

Finally, a look at external relations. Since the fall of Saddam’s regime, Iran and the United States have mainly vied for influence in Iraq.

Iraq has close ties with Iran in politics, economics, and culture. During Saddam’s rule, Iran sheltered Shiite forces who were persecuted. Many Shiite leaders who returned to Iraq after Saddam’s fall and entered government have strong ties to Iran. Iran has provided funding and training to Shiite parties and allied militias. These militias have also suppressed protests against Iranian interference, giving Iran indirect influence over Iraq’s politics and security. Iran is also Iraq’s largest trading partner, with heavy dependence in the electricity sector: as of 2021, about 35% of Iraq’s electricity relied on natural gas and power imports from Iran. There are also many cultural commonalities, with both countries having Shiite Muslim majorities and large Kurdish populations. Iran has also carried out attacks on Iranian Kurdish opposition groups who fled to northern Iraq.

U.S. forces during the invasion of Iraq (Photo: Lance Corporal Kevin C. Quihuis Jr. (USMC)Sgt.Luciano Carlucci (USMC) / Wikimedia Commons [PDM])

The United States, for its part, invaded Iraq in 2003, toppled the Hussein regime, and began an occupation. Under the occupation, it dismantled the Ba’ath Party and introduced an ethnicity-based political system. This ultimately brought division and chaos to Iraq and led to sectarian conflict and the rise of IS. When IS expanded in 2014, at the request of the Iraqi government, U.S. forces returned after their 2011 withdrawal and undertook major military operations. Since then, through training, aid, and support, the U.S. has expanded its influence and continued its presence even after IS’s decline. Since 2003, about 200,000 civilians have been killed in fighting and terrorist attacks.

Iraq’s situation is buffeted by U.S.–Iran confrontation. Undermining each other’s influence in Iraq is one of their goals. In January 2020, U.S. forces assassinated Iranian commander Qassem Soleimani while he was visiting Iraq. In the wake of the incident, the Iraqi parliament called for the early withdrawal of U.S. forces. Iran-backed Iraqi militias have repeatedly attacked U.S. bases and other targets. As of 2021, U.S. forces in Iraq ended combat operations but continued training and support, and while troops remain, attacks on bases have also continued.

Neighboring Turkey has also expanded military action in Iraq due to the Kurdish issue. It occupies parts of northern Iraq, and as of 2023 continues intense airstrikes. Since the 1980s, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) has waged an armed struggle in Turkey seeking an independent state, and Turkey considers the PKK a “terrorist group.” Because the PKK is based in northern Iraq, Turkish forces have repeatedly targeted the region. Meanwhile, Turkey maintains friendly relations with the KDP, which supports its fight against the PKK, and has built good relations with the Kurdistan Regional Government on energy projects, exporting crude through a dedicated pipeline between Turkey and the Kurdistan Region. Turkey, which lies upstream of Iraq’s rivers, is also involved in disputes over the allocation of water resources.

Conclusion

Despite abundant oil and human resources, Iraq’s elite-centered, corruption-ridden government—caught between the U.S. and Iran—has failed to make the most of them. Pushing the oil industry further risks causing environmental pollution, health damage, and climate change, which in turn worsen water shortages—a potential vicious cycle. Localized conflicts still persist, and security remains unstable. Will fundamental political and economic reforms advance to stabilize Iraq and improve people’s lives? We will keep watching developments in Iraq.

※1 A nationalist idea that emerged from the late 19th to early 20th centuries, aiming for cultural and political unity among Arab countries.

Writer: Chika Kamikawa

Graphics: Ayane Ishida

0 Comments