The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is one of the countries with the world’s highest number of executions. It is also the only country where the death penalty is carried out by beheading by sword. By October 2025, at least 302 people had been executed in the country, and despite Saudi authorities’ claims that they are restricting use of the death penalty, the number has continued to rise each year. On October 20, a man who had participated in a protest when he was 17 years old was executed, among other cases, highlighting the frequent use of capital punishment against minors and in ways that violate international law in Saudi Arabia.

In 2016, the Saudi government announced a national policy called “Vision 2030,” setting goals to restructure the country economically, socially, and politically by 2030. However, in Saudi Arabia, human rights abuses and efforts to suppress criticism of the government are conspicuous, and there are strong indications that “Vision 2030” is being used to conceal inconvenient domestic realities and deflect international scrutiny.

This article looks, with attention to Saudi Arabia’s history and customs rooted in Islamic culture, at the achievements of “Vision 2030” as of 2025—five years out from 2030—and the many contradictions it contains, along with how those dynamics interact with and affect the outside world.

Landmarks of Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia (Photo: B.alotaby / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0] )

目次

History of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Islam

The modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a relatively young state founded in 1932, named after the ruling House of Saud. The foundation goes back to 1727, when Muhammad bin Saud, then ruler of the town of Diriyah, and Sheikh Muhammad bin Abd al-Wahhab, an Islamic scholar, established the first Saudi state. They sought to restore “pure” Islam (※) across the Arabian Peninsula as they expanded their state. Although it was destroyed by the Ottoman Empire in 1818, the House of Saud established a second Saudi state in 1824 with Riyadh as its capital. In 1891, this state was eventually defeated by the rival Rashidi dynasty backed by the Ottomans, and the House of Saud fled to neighboring Kuwait. However, in 1902 the Saudis reconquered Riyadh, and later founded the present kingdom, the third Saudi state. Although Britain maintained protectorate relations with neighboring states, it recognized Saudi Arabia as a state in the 1927 Treaty of Jeddah.

Saudi Arabia, whose national language is Arabic, is located between the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, in the birthplace of Islam, and the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina are administered by the royal family. The vast majority of citizens adhere to Sunni Islam, while the Shia minority, less than 10% of the population, faces discrimination and repression. The state is inseparable from Islam. Since 1744, an alliance between Muhammad bin Saud and Sheikh Muhammad bin Abd al-Wahhab, founders of the first Saudi state, established a tradition that the descendants of al-Wahhab would hold religious authority as “shaykhs,” while the House of Saud would hold political authority—an arrangement that continues to this day.

Yet religion and politics have often been at odds. After oil, discovered in large quantities in 1938, enriched the state during the oil crises of the 1970s, foreign technology, information, entertainment, and culture flowed in. As modernization advanced, religious strictures loosened in daily life. As this cultural openness spread, in 1979 a group of militant Islamists led by Juhayman al-Otaybi, who condemned the royal family for moral and religious decline, carried out an armed seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, which attracts 50,000 people from around the world. After the suppression of this attempt to restore a conservative Islam, the royal family became more cautious, refocused on a religious revival, and moved to promote a more strict Islam.

A pilgrim offering prayers at the Holy Mosque (Photo: Ali Mansuri / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.5] )

Intertwined international relations

From 1979 to 1989, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, a predominantly Muslim country. In response to the expansion of a non-Muslim power, the Saudi government recruited volunteers by promising paradise to those who fought the Soviets. Seizing the opportunity, the government used the Islamic concept of jihad—“military struggle in defense of Islam”—to expel conservative Islamic opponents abroad as foreign fighters in Afghanistan.

However, when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, the Saudi government, feeling threatened, allowed U.S. forces to station near the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Allowing non-Muslim forces near the holy sites, combined with the resentment of returning Afghan veterans who felt betrayed, brought opposition to the royal family’s disregard for Islam to a peak. This backlash also became a factor in the later rise of the extremist group al-Qaeda. The government tried to quell activities such as attacks on U.S. bases and the spread of anti-government ideas via cassette tapes through surveillance, repression, and bribery.

Saudi Arabia also struggled with a dispute over the border with Qatar. Although parts of the border were demarcated in 1965, it remained ambiguous. A military clash occurred at a border checkpoint in 1992, and tensions escalated. In 2002, Al Jazeera, Qatar’s media outlet, repeatedly broadcast reports on Saudi royal corruption and human rights issues via satellite, prompting Saudi Arabia to recall its ambassador from Doha and freeze diplomatic relations.

Signs of improvement appeared briefly in 2007, with a deal to demarcate the border and a Qatari commitment to tone down coverage of Saudi-related issues. Although the border line was set, fundamental disagreements remained, and tensions continued. In 2017, Saudi Arabia, together with the United Arab Emirates and other Arab states, broke off diplomatic relations. Demands included ending “support for terrorism” and closing Al Jazeera, but ties were restored in 2021.

The rise of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman

In principle, the Saudi throne passes to a direct male descendant of the House of Saud, and when a king dies, the crown prince approved by the Allegiance Council becomes the next king. When King Salman bin Abdulaziz ascended the throne in January 2015, change followed. His son, Mohammed bin Salman, known as MBS, was appointed Minister of Defense and stepped into the limelight.

In the Yemen war that escalated in 2014, the Ansar Allah movement (also known as the Houthis), largely composed of a branch of Shia Islam, seized the capital. To counter this, Saudi forces led by MBS, together with the United Arab Emirates and other Arab states, intervened in March 2015. The more than 25,000 airstrikes conducted caused massive damage, indiscriminately targeting civilians, migrants, schools, hospitals, and farms, and torturing detainees, among other abuses. Saudi Arabia’s intervention has been blamed for escalating the conflict and creating one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. The Yemen conflict has resulted in at least around 400,000 deaths.

Domestically, MBS consolidated power amid the king’s poor health and an aging royal family. In early 2015, King Salman created the Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA) and appointed MBS as its chair. In March 2015, oversight of Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) was transferred to CEDA. PIF is the sovereign fund established in 1971 to effectively deploy revenues from oil. In other words, MBS came to control the nation’s finances.

In June 2017, MBS was elevated to crown prince. That November, 381 princes and senior officials were detained at the five-star Ritz-Carlton in Riyadh as part of an anti-corruption campaign. After torture, they were released in exchange for forcibly handing over some US$80 billion in total to the state. This is seen as how MBS purged princes who could have been rivals.

Mohammed bin Salman attends the Counter-ISIL Ministerial Plenary Session at the U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C., July 21, 2016. (Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain] )

“Vision 2030” and domestic reforms

When oil prices fell in 2014, it dealt a blow to Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter. Moreover, oil, which at the time accounted for 85% of Saudi Arabia’s total revenue, was projected to reach peak production and demand by 2030. In April 2016, MBS announced “Vision 2030,” a set of goals to diversify the economy away from oil by 2030. The plan emphasizes not only economic diversification but also social and cultural approaches, and MBS has signaled opposition to a strictly conservative Islam, criticizing the Wahhabi establishment.

Let’s look at the outline and progress of “Vision 2030.” The plan positions Saudi Arabia to strengthen domestic industry and serve as a hub connecting Europe, Africa, and Asia, as well as to exercise leadership as the center of the Arab world and Islam. It sets out three themes—“Vibrant Society,” “Thriving Economy,” and “Ambitious Nation”—each with specific targets. Of 1,502 targets in total, the government says 85% were on track by 2024, with 674 already completed.

Under “Vibrant Society,” the aim is to improve quality of life and identity through social and cultural development. For example, the homeownership rate target for Saudis is 70%. It rose from 47% in 2016 to 64% in 2024. There is also a goal to increase average life expectancy from 77 to 80 years; as of 2024, it stands at 78. Furthermore, the plan seeks to increase annual foreign pilgrims for Umrah, one of the Islamic pilgrimages to Mecca, to 30 million. Although the number has risen significantly from 6.2 million in 2016, it was 16.9 million in 2024. Other goals include building museums, listing sites on UNESCO’s World Heritage list, and strengthening education.

Under “Thriving Economy,” the plan calls for expanding the industrial base through privatization of state-owned enterprises, investing in non-oil sectors, and creating several megacities. For instance, the unemployment rate target is 7%, down from 11.6% in 2016 to 8.6% in 2024. Women’s labor force participation surpassed the 30% target, reaching 36% in 2024. PIF’s assets exceeded US$940 billion in 2024, and the target has been raised to US$2.67 trillion. The target for the private sector’s share of GDP is 65%; it rose slightly from 40% in 2016 to 46% in 2024. However, the share of non-oil exports, defense localization, and foreign direct investment remain far below targets.

Under “Ambitious Nation,” the plan aims for a more transparent and productive state, improving fiscal efficiency and taking a tough stance on corruption. Specific measures include government digitization and streamlining, promoting volunteerism in line with Islamic morals, and increasing non-profit organizations—all of which the government claims are yielding steady results.

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 at a UN General Assembly side event (Photo: United Nations Development Programme / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0] )

As part of the reforms, in April 2016 MBS curtailed the powers of the religious police. For years they enforced Islamic codes in public life, including interactions between men and women and women’s dress, but their excessive activities often amounted to harassment and even deaths, leading to public discontent.

The death penalty issue

Amid such reforms, serious government human rights abuses have repeatedly occurred in Saudi Arabia. First, as noted at the beginning of this article, the frequency of executions is a major concern. According to the European Saudi Organization for Human Rights (ESOHR), 345 people were executed in 2024, the highest number in a decade. By October 2025, the total had already reached 87% of the 2024 figure.

Of the 1,816 executions carried out between 2014 and June 2025, the vast majority were for terrorism and drug-related charges. The definition of terrorism is vague, and participation in demonstrations against the government can be deemed terrorism. Some of those sentenced to death on terrorism charges had protested against megacity projects under “Vision 2030.” For example, in 2022, three residents protesting forced evictions for the construction of the NEOM megacity were sentenced to death on terrorism charges. Moreover, using the death penalty for drug offenses violates international human rights law, which says capital punishment should be reserved for “the most serious crimes.” Saudi Arabia has been a member of the UN Human Rights Council since 2022, and although MBS declared that “the death penalty will henceforth be applied only to murder,” that pledge has been openly violated.

Saudi Arabia has no penal code; judicial rulings are based on Sharia, Islam’s moral-legal framework. Under Sharia, definitions are not always clear, and judgments are often made using vague standards. Sharia punishments are broadly divided into three types: ta’zir, qisas, and hadd. Ta’zir is at the discretion of the ruler and is used broadly based on the judgments of the ruler or the Ministry of Justice, often for political repression such as protests, drug offenses, and “supporting terrorism.” Qisas applies in cases such as murder, granting the victim’s family rights under the “eye for an eye” principle. Hadd are fixed punishments prescribed in the Quran, including for adultery and theft.

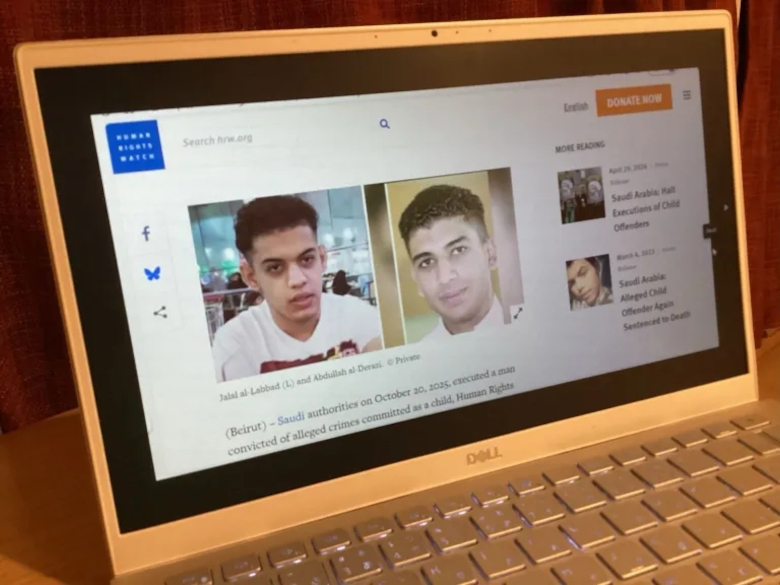

Article by Human Rights Watch on the execution of a man who was a minor at the time of the crime (published October 20, 2025)

In 2025, two men were executed for crimes they had committed as minors. They had participated in protests in 2011 and 2012 against government abuse of Shia when they were under 18, were sentenced to death under ta’zir, and were forced to confess under violence during detention. This violates the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Saudi Arabia is a party, and breaks the Saudi authorities’ own 2020 pledge to abolish the death penalty for minors.

Other human rights issues

Beyond the death penalty, violations of women’s rights are also in the spotlight. Saudi Arabia has a male guardianship system rooted in the Islamic notion that women should be under male protection. As a result, women historically could not work or travel abroad without male permission, access medical care, obtain a divorce, or even drive. In 2018, as part of “Vision 2030” to promote women’s employment, the driving ban on women was lifted. However, contrary to that move, the government has repressed many activists who had campaigned for the right to drive or protested for women’s rights, arresting and imprisoning them.

In 2019, some aspects of the guardianship system were eased, allowing women to travel abroad without male permission. For a long time, women had no legally defined age of majority. The Personal Status Law announced in 2022 finally set women’s legal adulthood at 18. However, it also permits marriage under 18 and codifies elements of guardianship, drawing criticism for enabling child abuse and domestic violence.

Freedom of expression is also strictly curtailed. Authorities monitor internationally visible media criticism of the government and promote favorable views of Saudi Arabia. In June 2025, Turki al-Jazer, who had exposed royal corruption via an account on the social platform X, was arrested, detained, and executed. The state also pursues Saudis abroad who criticize the royal family. In 2018, the killing of Saudi writer and journalist Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi officials at the Saudi consulate in Turkey drew global attention. He had long criticized the Saudi government in English-language media and advocated reform, living in exile in the United States.

International Women’s Day 2019 campaign for Saudi women activists (Photo: Hayfa Takouti / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0] )

Abuses against migrants have long been a concern. About 42% of Saudi Arabia’s total population are migrant workers, who form a major labor force in domestic development such as megacity construction seen in NEOM. Migrant workers are governed by the “kafala” sponsorship system, which ties a worker’s legal status to their Saudi employer and often leads to abuse.

Migrant workers are sometimes misled into signing contracts as waiters or domestic workers, only to end up in outdoor construction or factory jobs. They face long working hours and poor living conditions, and under harsh conditions—including extreme heat—many lose their lives. Under kafala, employers commonly confiscate passports, making job changes difficult; voicing grievances or seeking to change jobs can result in exorbitant fees or deportation. Labor unions and strikes are illegal in Saudi Arabia, making it hard to address abuses. Wage non-payment after work is also common.

Human rights issues concealed by international PR

As part of “Vision 2030,” Saudi Arabia is investing heavily in sports to promote public health, elevate the status of women, and energize society and the economy. The government has spent on the order of billions of dollars to bid for and host international sporting events such as Formula 1, boxing, wrestling, and top-flight football leagues, in an effort to attract them. There is also a strategy to brand Saudi Arabia by investing in internationally renowned organizations and rallying domestic and international support, thereby spurring foreign investment in the country.

But the goals seem to go further. Some argue that popular sports at home and abroad are being used to hide serious domestic human rights abuses—so-called sportswashing. In 2023, the PGA Tour, which operates a U.S.-based men’s professional golf tour, announced plans to merge its golf business and rights with those of Saudi Arabia’s PIF. However, because the deal reportedly included a non-disparagement clause, the PGA Tour delayed signing amid concerns about Saudi human rights, and negotiations have stalled. When Argentine footballer Lionel Messi was appointed Saudi tourism ambassador in 2022, his contract with the Saudi tourism authority reportedly included a clause prohibiting statements that could damage Saudi Arabia’s reputation, in exchange for US$2 million and 10 annual social media promotions of the country. The FIFA World Cup will be held there in 2034, and the human rights abuses that could occur behind the scenes are a matter of concern.

King Fahd International Stadium (Photo: على المزارقه / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0] )

The same pattern appears in entertainment events beyond sports. At a comedy festival hosted in Riyadh in September 2025, internationally popular comedians—many from the United States—were invited. However, the large fees offered reportedly came with a clause prohibiting “defamation” of the Saudi government. Some comedians declined to participate, citing suppression of free speech and complicity in serious human rights abuses. One participant was fired for joking about Saudi Arabia’s human rights violations.

The Saudi government has also signed massive contracts with major foreign PR firms to spread a positive image of the country, branding and promoting Saudi Arabia to the world via official websites and social media.

This series of government moves has been criticized as “sportswashing,” “PR-washing,” and “whitewashing.” The term “washing” implies covering up scandals or bad reputations with other positives. The Saudi government is using public funds for such investments, diverting attention from human rights issues and masking domestic wrongdoing.

Major powers that “cooperate”

Saudi Arabia’s authoritarian system, human rights abuses, and destabilizing actions such as military intervention in Yemen are also enabled by the behavior of other governments, which in turn helps muffle and downplay criticism of the Saudi government.

U.S. President Donald Trump and MBS enjoy close ties, and in May 2025 Saudi Arabia agreed to invest US$600 billion in the United States. The UK also deepened relations by signing a trade and investment deal in October 2025. However, both countries export large quantities of weapons to Saudi Arabia, drawing condemnation from international human rights groups for contributing to human rights abuses and mass killings in the Yemen conflict. Japan is also expanding investment, with Japanese companies participating indirectly in human rights abuses through involvement in the NEOM megacity project.

President Donald Trump attends a welcome ceremony with MBS in Riyadh on May 13, 2025 (Photo: The White House / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain] )

Responsibility for Saudi Arabia’s human rights abuses no longer lies solely within its borders. How foreign governments and companies—connected through military, economic, sports, and entertainment ties—engage with Saudi Arabia and address its problems will be key to improvement. How will the contradiction between Saudi Arabia’s development and the violation of fundamental human rights evolve?

※ The Wahhabi movement originates with Sheikh Muhammad bin Abd al-Wahhab and strictly adheres to the Quran. It regards itself as true Islam, does not recognize other sects or religions, and often undertakes reform movements.

Writer: Morita Aoba

Graphics: A. Ishida

WOWPH11 Casino Online Philippines: Easy Login & Register, Download App, and Play Top Slot Games. Join WOWPH11 Casino Online Philippines! Experience top WOWPH11 slot games with easy WOWPH11 login & register. WOWPH11 download app now to play and win big today! visit: wowph11

[1265]SS7777 Login, Register & Slot Games: Download the SS7777 Official App for the Best Casino Experience in the Philippines. Join SS7777 for the best casino experience in the Philippines! Quick ss7777 login & register to play ss7777 slot games. Download the ss7777 official app now and win big today! visit: ss7777

[4907]93jl Online Casino: Official 93jl Login, Register, & App Download for Best Slots in the Philippines Experience 93jl Online Casino, the Philippines’ top platform for premium gaming. Secure your 93jl login or 93jl register to play 93jl slot games. Get the 93jl app download and win big today! visit: 93jl

[2118]Winph777 Online Casino Philippines: Secure Login, Easy Register, and App Download for Top Slot Games. Experience Winph777 online casino Philippines! Enjoy secure winph777 login, fast winph777 register, and top winph777 slot games. Get the winph777 app download now for elite gaming. visit: winph777

[7157]Joyjili Casino Online Philippines: Play Top Slot Games, Easy Joyjili Login & Register. Get the Official Joyjili App Download for the Ultimate Gaming Experience! Join Joyjili Casino Online Philippines! Play top Joyjili slot games with easy Joyjili login and register. Get the official Joyjili app download for the ultimate mobile gaming experience today! visit: joyjili

[6078]337jili Online Casino PH: Login, Register, & App Download for Best Slot Games Experience the premier 337jili Online Casino PH. Secure 337jili login, fast 337jili register, and 337jili app download for the best 337jili slot games and big wins! visit: 337jili

[92]2jl Casino Philippines: Best 2jl Slot, Easy Login, Register & App Download Experience the best 2jl slot games at 2jl Casino Philippines. Enjoy a fast 2jl login, easy 2jl register process, and a seamless 2jl app download. Join the premier 2jl casino today and start winning big! visit: 2jl