2025 marks ten years since the political crisis in Burundi began. This crisis started in 2015 when then-President Pierre Nkurunziza announced he would run for a third term. Protests against this decision, which was denounced as unconstitutional, broke out but were harshly repressed by security forces.

The national and local elections held in June 2025 offered a chance to gauge shifts in Burundi’s political landscape. In this election, the ruling party won all 100 seats in parliament, with its vote share exceeding 95 percent. It also secured numerous seats at the local level. Opposition leaders have challenged this overwhelming victory. Human rights groups reported irregularities in the electoral process and that various freedoms were restricted.

Armed conflict lasted in Burundi from 1993 to 2005. While security has stabilized to some extent, political repression persists. To understand the current situation, this article traces Burundi’s history before and during the colonial era and after independence.

President Ndayishimiye (left) celebrating Burundi’s Independence Day, 2021 (photo: LLainivonie / Shutterstock.com)

目次

Overview

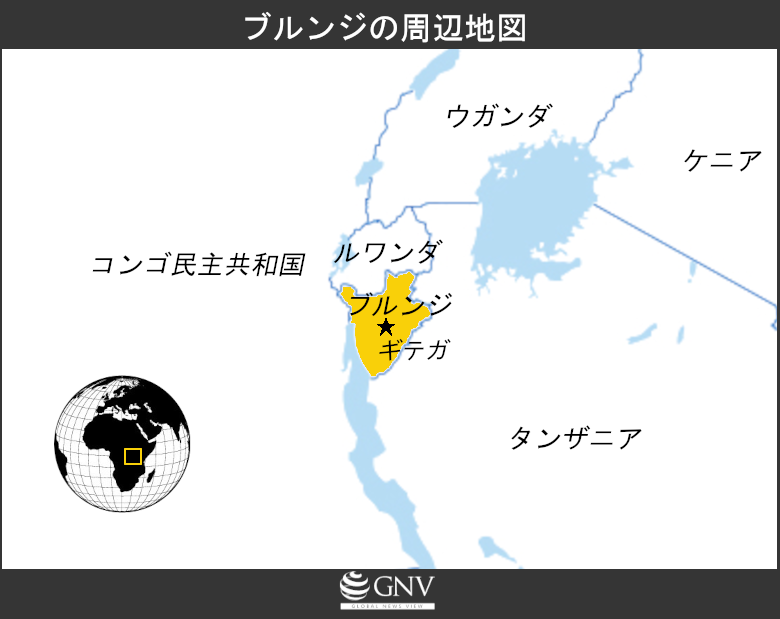

The Republic of Burundi is a landlocked country in East-Central Africa, with an area of about 28,000 square kilometers. It borders Tanzania to the east and south, Rwanda to the north, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to the west, and is part of the so-called “African Great Lakes region.” It was once a monarchy and is one of the few African countries whose borders were not determined by colonial rule. The largest city is Bujumbura, which was the capital until 2019. It is now considered the economic center, while Gitega serves as the political capital. Urbanization has progressed relatively slowly, and the share of the population living in cities is low.

Burundi’s population is estimated at about 14 million as of 2025. Population density is roughly 560 people per square kilometer—extremely high. The infant mortality rate in 2024 stood at 35 per 1,000 live births, and those under age 15 account for 45 percent of the population, while only 3 percent are over 65. In terms of ethnic identity, about 85 percent of Burundians are Hutu, 14 percent are Tutsi, and 1 percent are Twa, estimated figures. However, there are few cultural or religious differences between Hutu and Tutsi (the majority are Catholic), and both speak Kirundi. Such linguistic uniformity is rare in sub-Saharan Africa and reflects Burundi’s history as a unified kingdom. The literacy rate is about 70 percent, considerably below the global average of 85 percent.

Burundi’s main economic activity is agriculture, with coffee and tea as major export crops. There are also undeveloped mineral resources, and Lake Tanganyika provides resources for fishing and hydroelectric power. The currency is the Burundian franc. In 2024, Burundi’s GDP was 2.16 billion USD, and GDP per capita was 153.9 USD. As of 2020, more than 96 percent of the population lived below the ethical poverty line of $7.4 per day (※1).

Pre-colonial and colonial Burundi

For centuries, Burundi was an organized and relatively stable kingdom. The area that is now Burundi was originally inhabited by the Twa, a Pygmy hunter-gatherer people. Later, people known as Hutu (farmers) and Tutsi (pastoralists) migrated to the region, but the distinction between them was not clear-cut. The kingdom emerged in the 16th century. The Burundian kingdom was led by a Tutsi royal dynasty, but Hutu were also included among the nobility. Moreover, the boundaries between the two were fluid—for example, a Hutu who acquired a herd could be considered Tutsi—and interethnic marriages were frequent. According to cultural custom, a wealthy Hutu could be regarded as Tutsi, while a poor Tutsi could be considered Hutu.

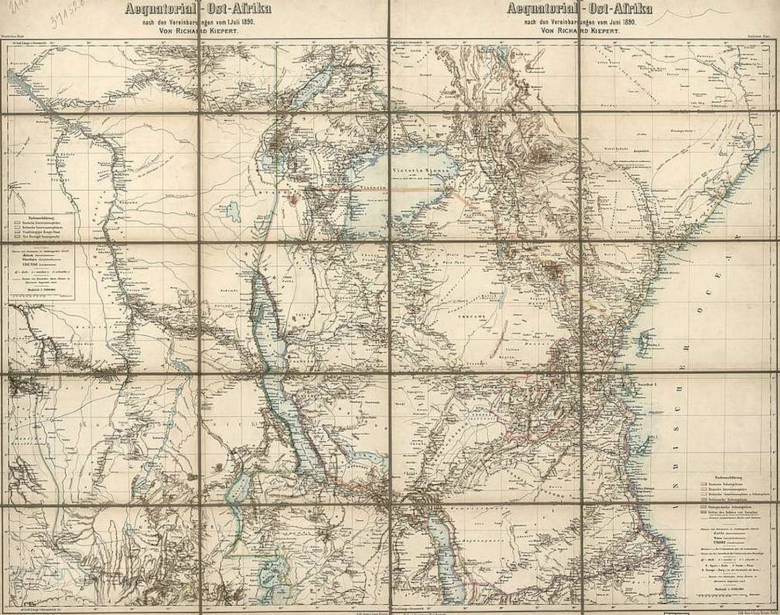

In the late 19th century, German forces began to penetrate the region of Burundi. By 1890, together with Rwanda and Tanganyika (now part of Tanzania), Burundi had been incorporated into the German East Africa Protectorate. After Germany’s defeat in World War I, Burundi and Rwanda came under Belgian control. In the late 1920s, Belgian colonial administrators curtailed the chieftaincy and removed many Hutu leaders from their positions. They also created and promoted a new class system that had not existed before the colonial era—one that favored the Tutsi minority. Belgian colonial policy was strongly influenced by the Catholic Church (※2) and the “Hamitic hypothesis” (※3), which became one factor in ethnic divisions in Burundi.

Although Africa was widely seen in Europe at the time as “savage and uncivilized,” traces of advanced civilizations across the continent strongly contradicted that perception. This led to the creation—or reworking outside its biblical origins—of the “Hamitic hypothesis.” According to this hypothesis, “Hamites” were pastoralist peoples of European origin who dominated the indigenous “black Africans” and built civilizations. In other words, it was thought impossible that blacks deemed “uncivilized” could independently develop advanced political and religious institutions; there must have been involvement by a supposedly “superior race” from outside.

In Burundi, the hypothesis was used to justify the view that “the Tutsi are Hamites, migrants, and a superior race distinct from the indigenous Hutu.” Such explanations were repeated for decades and came to be accepted as fact. This racial categorization fit well with the objective of “divide and rule” in an otherwise orderly society and dovetailed neatly with the colonial narrative of bringing “civilization” to “uncivilized blacks.”

East-Central Africa, 1890, produced in Germany (photo: Library of Congress / Picryl [Public domain])

In Burundi, the Tutsi—cast as a minority of “early migrants”—were used as allies to “civilize” the Hutu majority. German and Belgian colonial rulers placed Tutsi in positions of power and ruled through them. The distinction between Hutu and Tutsi was made largely on the basis of physical features (such as height and facial structure). Decades of such colonial policies greatly exacerbated Hutu–Tutsi antagonism. A similar situation occurred in neighboring Rwanda and became one of the triggers of genocides in both countries.

Burundi after independence

The drive for independence by Burundians advanced significantly with the formation in 1958 of the Union for National Progress (UPRONA), the first multiethnic party in the country. In preparation for independence, a constitution was adopted that kept the traditional monarchy—then dominated by Tutsi—while introducing an elected prime ministership to lead the country’s politics and economy. In the 1961 legislative elections, UPRONA won, and a Tutsi prince became prime minister and organized a new administration. Although his assassination destabilized the situation, Burundi achieved independence on July 1, 1962.

Post-independence Burundi in many ways was an extension of the colonial order. Politics and the military remained in the hands of the Tutsi minority, creating tensions with the Hutu majority. Political confrontation intensified and gradually took on the character of ethnic conflict. By then, massacres by both Hutu and Tutsi were reported, and two prime ministers were assassinated. Burundi shifted from a constitutional monarchy to a republic, and in the same year the Tutsi Michel Micombero became the first president of the First Republic.

Now head of state, Micombero built an authoritarian regime dominated by the Tutsi and UPRONA, which by then had become a de facto one-party system. In 1972, large-scale interethnic violence erupted again, and an estimated 100,000–300,000 people were killed. Around 200,000 Hutu fled to Tanzania, Rwanda, and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). That year also saw the start of a Hutu rebellion aiming to overthrow the Tutsi-led government: the Party for the Liberation of the Hutu People – National Liberation Front (PALIPEHUTU-FNL, or FNL).

Burundian soldiers (photo: US Army Africa / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

In 1976, the Micombero regime was overthrown in a coup led by Tutsi Lieutenant Colonel Jean-Baptiste Bagaza, ushering in the Second Republic. The new government sought to restrict the social and educational activities of the Roman Catholic Church, as the Church’s policies were seen as favoring the Hutu. To many Tutsi, the Catholic Church appeared to be a dangerous threat to the regime.

In 1987, amid tensions between the state and the Catholic Church, Tutsi Major Pierre Buyoya launched a coup, toppling the Second Republic and establishing the Third Republic. Buyoya lifted various restrictions on religious activity and freed political prisoners. Ironically, his move toward easing repression raised Hutu expectations, but the structure of Tutsi dominance persisted, and new interethnic violence erupted in 1988. In response, the president appointed a Hutu prime minister and several cabinet ministers. This led to Buyoya’s reputation as a moderate, which grew further from 1990 onward as he signaled his acceptance of a democratic political system.

The 1992 constitution established separation of powers and restored a multiparty system. Notably, it required all political parties to include representatives from both Hutu and Tutsi. In 1993, Burundi held its first free presidential election, which was won by Melchior Ndadaye, the candidate of the predominantly Hutu Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU). The defeated Pierre Buyoya accepted the result and stepped aside. Ndadaye thus became Burundi’s first Hutu president. His administration released many political prisoners and inaugurated a government of Hutu–Tutsi cooperation by appointing a Tutsi, Sylvie Kinigi, as prime minister. However, Ndadaye was assassinated a few months after taking office, and political turmoil began between the Tutsi-dominated army and Hutu rebel forces.

A decade of armed conflict

The October 1993 assassination of Ndadaye plunged the country into armed conflict that continued into the early 2000s. By the end of 1993, more than 100,000 people had been killed in political violence. Hutu political leaders went underground, took up arms, and in 1994 formed the National Council for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD). Its armed wing, the Forces for the Defense of Democracy (FDD), became the main insurgent movement in Burundi. Internal disputes and purges produced two principal factions: the CNDD led by Léonard Nyangoma and the CNDD-FDD led by Pierre Nkurunziza. CNDD-FDD fought not only the Tutsi-dominated Burundian army but also the FLN, an existing Hutu rebel group.

Former President Buyoya speaking at the United Nations, 2015 (photo: UN Geneva / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In January 1994, Hutu politician Cyprien Ntaryamira was elected president, but he died a few months later when his plane was shot down. Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana also perished in the incident, which triggered the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Ntaryamira’s successor, Sylvestre Ntibantunganya, also a Hutu, failed to assert authority over hardliners on both sides, and in 1996 Tutsi soldiers overthrew the government. They appointed former president Pierre Buyoya as head of state in an attempt to restore international confidence with his good image. The United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU) condemned the coup, and neighboring countries imposed an embargo on Burundi. The embargo was eased in 1997 and fully lifted in 1999.

Neighboring countries actively engaged in efforts to resolve Burundi’s armed conflict. In 1998, former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere led peace talks in Arusha, Tanzania, bringing together the government, Hutu and Tutsi opposition parties, and rebel forces. After Nyerere’s death, former South African President Nelson Mandela took over as mediator. However, ceasefires emerging from these talks were repeatedly broken.

In 2000, the government and 16 armed groups and parties signed the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi. The agreement established a multinational interim security force and mandated peacekeeping in Burundi. It also provided for two consecutive 18-month periods, with Tutsi and Hutu presidents alternating at the end of the first period. This arrangement officially began in 2001 under President Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) and Vice President Domitien Ndayizeye (Hutu).

State weakness and armed conflicts in several countries in the African Great Lakes region contributed to prolonging the war. For example, Hutu rebels used South Kivu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as an operational base, and the Burundian army pursued them into the DRC. In this conflict, the Burundian and Rwandan armies also attacked camps of unarmed civilians.

Disarmament of rebel forces, 2005 (photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In 2002, a ceasefire was reached between President Buyoya and CNDD-FDD leader Pierre Nkurunziza, improving the situation. However, the FNL refused to join the agreement and continued guerrilla warfare. Under the Arusha Agreement, President Buyoya transferred power in 2003 to Hutu Vice President Domitien Ndayizeye. Nkurunziza’s CNDD-FDD signed the peace accord, became a political party, was integrated into the regular army, and was allowed to join the government. This last provision was one of the most difficult parts of the peace process, as command of the army had long been monopolized by Tutsi officers. The success of this decisive step was aided by the presence of the United Nations Operation in Burundi (ONUB).

At the end of the transition, the CNDD-FDD’s signing of a power-sharing agreement between Hutu and Tutsi for future state institutions marked an important milestone. In 2004, a new national army was created with equal numbers of Hutu and Tutsi mandated, and more than 20,000 former CNDD-FDD rebels were absorbed.

Ten years of peace?

In 2005, Burundians approved a new constitution by referendum that made power-sharing between the two main ethnic groups more equitable. Under the new constitution, the president is directly elected for a five-year term and may be re-elected once. Seats in the National Assembly and Senate are allocated proportionally. The CNDD-FDD won the 2005 local, legislative, and Senate elections. The victory was sealed when the party’s leader, Pierre Nkurunziza, was elected president of the republic by parliament. The following year, the last rebel movement, Palipehutu-FNL, reached a ceasefire agreement with the government. Under Agathon Rwasa, the FNL transformed into a political party, the National Congress for Freedom (CNL).

In 2010, Nkurunziza was re-elected with more than 90 percent of the vote after all six rivals withdrew amid electoral violence and low turnout. His second term grew increasingly authoritarian, with attacks on freedom of expression and judicial independence. Opposition figures such as CNDD chairman Léonard Nyangoma fled abroad to Belgium. Intermittent political violence also recurred. These renewed incidents and protests were primarily political rather than ethnic, which is seen as evidence that the peace process succeeded in overcoming ethnic divisions.

Scene from the presidential election, 2010 (photo: Brice Blondel / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

In 2015, Nkurunziza’s decision to run for a third term created further tensions. Many Burundians viewed recognizing an extension of the presidential term without national consensus as a violation of the 2000 Arusha Agreement and a major breach of trust. Nkurunziza, meanwhile, argued that his first term had been based on election by parliament rather than by the people and therefore did not count toward the two-term limit.

The announcement triggered mass protests by the “Anti-Third Term” movement, which brought together many civil society groups and two trade unions across ethnic lines. To counter the discontent, the CNDD-FDD’s youth wing, the Imbonerakure—seen as a pro-government militia—harassed and abused opposition members and intimidated Burundians who opposed the third term bid. As a result, tens of thousands of Burundians fled abroad in early 2015.

In May 2015, while Nkurunziza was in Tanzania for a meeting on Burundi’s political situation, a coup attempt took place. Several senior officers declared that Nkurunziza had been deposed and the government dissolved. Pro-government commanders resisted the rebellion, violence broke out, and the attempted coup ended. In July 2015, parliamentary, municipal, and presidential elections were held, drawing strong criticism from UN observers. Nkurunziza was re-elected with 69.4 percent of the vote. His rival Rwasa disputed the result but took part in the National Assembly and was elected deputy speaker.

Nkurunziza’s third term

As the third presidential term began, a series of assassinations heightened fears of renewed conflict. This concern was compounded by the formation of a new rebel group, the Burundian Republican Forces (FOREBU), which aimed to oust Nkurunziza by force. Despite this, Nkurunziza focused on consolidating his and his party’s grip on power through violent repression and systematically obstructed peace initiatives by the African Union and the United Nations. As international condemnation of human rights abuses in Burundi grew, an investigation by the International Criminal Court (ICC) was sought. Burundi subsequently notified the UN of its intention to withdraw from the ICC in 2016 and in 2017 became the first country to leave the court.

President Nkurunziza, 2010 (photo: Paul Kagame / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In 2018, amid ongoing intimidation, violence, and terror, a controversial constitutional referendum was held. Among other changes, the reform extended the presidential term to seven years, renewable for two consecutive terms. Despite widespread criticism, 73 percent of voters approved the changes. Talks between the government and the opposition in exile yielded no results.

To many people’s surprise, although he was eligible under the constitution, President Nkurunziza announced that he would not run in the 2020 election. As the election approached, talks resumed between parts of the opposition and the government. The CNDD-FDD nominated General Évariste Ndayishimiye as its presidential candidate. In the 2020 election, Ndayishimiye won easily with 68.7 percent of the vote, far ahead of main opposition candidate Rwasa. Rwasa denounced the poll as a “farce” marred by extensive fraud and intimidation. Nkurunziza was awarded the title of “Supreme Guide of Patriotism,” but he died suddenly before the new president’s inauguration.

Continuation of one-party rule

In the early part of his term, President Ndayishimiye promised to restore the rule of law, eradicate corruption and impunity, and promote political tolerance, aiming to end the international isolation of the Nkurunziza era. In 2022, international sanctions imposed after the 2015 unrest were lifted due to progress under Ndayishimiye.

However, observers note there has been no improvement in the human rights situation. Politically motivated verdicts, attacks on journalists, and incendiary rhetoric against human rights defenders remain rampant. For example, Ndayishimiye accused Prime Minister Alain-Guillaume Bunyoni of plotting a coup; in 2023, Bunyoni was arrested and later sentenced to life imprisonment for offenses including endangering national security, economic sabotage, and illicit enrichment. Multiple enforced disappearances have also been reported. Although the government has publicly called for refugees to return, many who have come back have been arrested and detained without trial.

Burundian refugees in Tanzania, 2015 (photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Ahead of the June 2025 legislative and local elections, repressive measures were implemented to weaken the opposition. Agathon Rwasa, founder and leader of the CNL, the strongest opposition to the CNDD-FDD, lost control of the party in his absence and claimed the government orchestrated the move. New regulations also made it virtually impossible for Rwasa and other perceived strong contenders to join other parties or run as independents.

Furthermore, the Burundian human rights group Iteka League sounded the alarm about abuses in 2024. It confirmed more than 210 killings, many of the victims affiliated with the opposition CNL. The Iteka League alleged that many perpetrators were linked to the government and that in most cases they went unpunished. Several political analysts contacted by international media refused to comment on the elections for fear of retaliation, and those who did speak requested anonymity.

The 2025 elections took place amid a severe gasoline shortage that prevented many politicians from campaigning. During the campaign period, many voters were compelled to vote, and opposition monitors were denied access to polling stations. One source noted that officials checked whether people had voted and that the Imbonerakure (the CNDD-FDD youth organization) harassed—and at times assaulted—voters. It was therefore no surprise that the ruling party easily secured all seats in parliament.

CNDD-FDD meeting place in a rural area (photo: Arthur Nkunzimana / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Summary

As we have seen, Burundi’s current political situation is repressive, and political leadership is often dominated by the ruling party through violence and intimidation. Freedom of the press and expression are severely restricted; journalists practice self-censorship, and those who do not comply with government demands are imprisoned.

The decline in interethnic violence has fostered hopes that the current relative peace can continue and open a path toward economic development and poverty reduction. However, political violence remains a major obstacle to such progress. It is hoped that President Ndayishimiye will not only fight corruption but also improve the current repressive climate and work toward holding transparent and fair elections for the future.

※1 GNV adopts the ethical poverty line ($7.4/day) rather than the World Bank’s extreme poverty line ($2.15/day). For details, see GNV’s article “How should we interpret global poverty?”

※2 Catholic missionaries were the first ethnologists in the region, and colonial governments sought their expertise when drafting racial policies. Moreover, most schools were run by missionaries.

※3 According to Genesis 9, Ham was cursed by his father Noah to be a servant to his brothers. Some biblical scholars interpret this curse as indicating that Ham’s descendants had black skin and migrated to the African continent.

Writer: Gaius Ilboudo

Graphics: MIKI Yuna

Is GGWinBet any good? Seeing it advertised everywhere. Would love to hear from anyone who’s actually used it. Thinking of trying ggwinbet this weekend.

Yo, 88vinapp is my go-to for quick games on my phone. Easy peasy to navigate and pretty decent payouts. Check it out 88vinapp.

Been using the jilipark app for a while now. It’s alright, gets the job done when I’m bored. Could be better but hey, it’s something. Worth a look at jilipark app if you’re looking for a time killer.

[3160]68jili Online Casino Philippines: Easy Login, Register & App Download for the Best Slot Games Join 68jili Online Casino Philippines! Experience easy 68jili login and register today to play the best 68jili slot games. Secure your 68jili app download for non-stop gaming action and big wins anytime, anywhere. visit: 68jili

[6258]Phpfamous: Best Slot Gacor Philippines. Login, Register, & Download APK for Real-Time RTP Live & Big Wins! Join Phpfamous, the best slot gacor in the Philippines! Login, register, or download the APK for real-time RTP live data and your chance at big wins. Play now! visit: phpfamous

[4583]JL77 Online Casino Philippines: Official Login, Register & App Download for Best Slot Games Join JL77 Online Casino Philippines for the ultimate gaming experience! Access the official jl77 login, quick jl77 register, and jl77 app download to enjoy premium jl77 slot games and exclusive bonuses today. visit: jl77

[5154]jililph app|jililph slots|jililph register|jililph giris|jililph download Experience the ultimate gaming thrill at jililph, the premier online casino in the Philippines. Play the latest jililph slots, complete your jililph register to claim exclusive bonuses, and enjoy seamless mobile gaming with a quick jililph download. Access the jililph app today via secure jililph giris login and start winning big! visit: jililph

[5013]King Login & Register: Play King Slot Online and Download the King App & Casino APK for the Best Gaming Experience in the Philippines. Experience King, the top choice for gaming in the Philippines. Fast king login & king register to play king slot online. Download king app & king casino apk now! visit: king

[7987]Philslot Online Casino: Top Slot Games, Easy Login, Register & App Download in the Philippines Join Philslot Online Casino for the best philslot slot games in the Philippines. Enjoy easy philslot login, fast philslot register, and get the philslot app download to win big today! visit: philslot

[7682]188jili Online Casino Philippines: 188jili Login, Register, & App Download for Top 188jili Slots Experience 188jili Online Casino Philippines! Quick 188jili login, register, & 188jili app download. Play top 188jili slot games and win today. Join the best in PH! visit: 188jili