On September 1, 2025, the UK’s Financial Times reported that the aircraft used by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen during her visit to the EU’s eastern countries “was subjected to GPS jamming suspected of Russian involvement” when it attempted to land at Bulgaria’s Plovdiv Airport on August 31 (Note 1). According to the article, the jamming forced the aircraft to circle above the airport for an hour before eventually landing using paper maps.

The news quickly spread worldwide and was picked up by major media outlets in many countries, most of which cited the Financial Times article as their primary source.

However, a close examination of the available evidence strongly suggests that the event either did not occur at all, or at least did not happen in the way the article described. On several important points, claims have been shown to be demonstrably false. In other words, this case represents a new example of how major media outlets, whether intentionally or not, became complicit in the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

This article examines the case and traces how this “news” was reported and circulated.

The same aircraft as the one that carried the President of the European Commission to Plovdiv (Photo: Anna Zvereva / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0] )

目次

Baseless claims

The reporting was built on a very shaky foundation from the start. The Financial Times appears to have based its piece on statements from three anonymous European Commission officials who were “briefed” on the incident, as well as remarks by a Commission spokesperson. While this cannot be verified, it is entirely possible that all of these officials had, in fact, been briefed by the same single internal source.

No evidence was presented—indeed, the spokesperson lacked even direct knowledge of the existence of such evidence. At the regular midday press briefing on September 1, the European Commission spokesperson claimed there had been “GPS jamming” and said they had received information from the Bulgarian authorities that they suspected “blatant interference” by Russia. However, when asked whether the Bulgarian authorities had provided any evidence to support this suspicion, the spokesperson admitted they had not received any. The spokesperson merely conveyed the Bulgarian authorities’ “suspicions,” and made clear that “it is up to the Bulgarian authorities to investigate.”

The Financial Times claimed that Bulgaria’s Air Traffic Services Authority “confirmed the occurrence of the incident in a statement to the paper.” Yet the article provided no direct quote of that “confirmation,” offering instead only a general remark that the authority acknowledged an increase in GPS jamming incidents since 2022. At that point, no one had directly confirmed with the Bulgarian authorities whether the incident had actually occurred, and no one appeared to have had access to any evidence.

A crumbling narrative

The Bulgarian government issued its first statement on September 1. In response to the reports, the Council of Ministers released a press release explaining that the aircraft carrying the President lost GPS signal while approaching Plovdiv Airport, but the crew immediately switched to ground-based navigation aids. This explanation is consistent with the ATC communications between the flight crew and airport controllers. The statement made no mention of malicious GPS jamming, the use of paper maps, or any delay to the flight. The next day, the Bulgarian government announced that it would not investigate the matter.

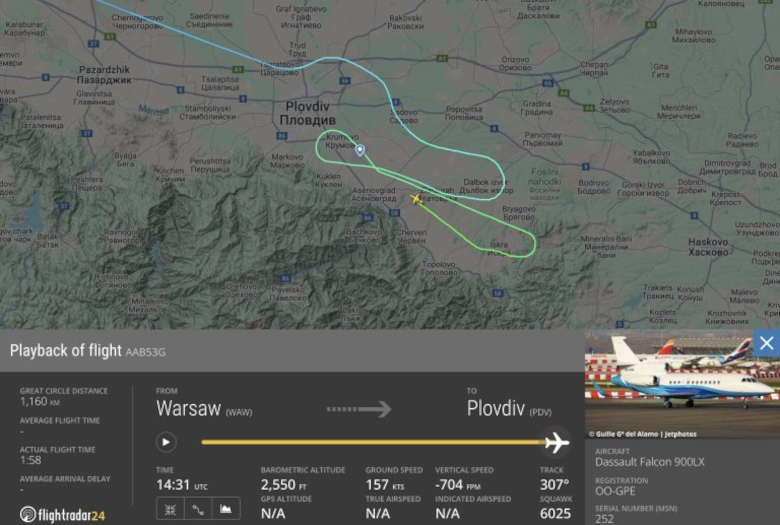

Actual flight path showing the landing of the aircraft carrying von der Leyen (published with permission of Flightradar24)

Neither the European Commission nor the Bulgarian government provided GPS data. Nor did the outlets that first reported the story. However, on the same day the Financial Times piece appeared, the Sweden-based flight-tracking service Flightradar24 (Flightradar24) published an analysis of the flight’s GPS data. It stated that “the aircraft’s transponder reported a good GPS signal from takeoff to landing,” and that the actual flight time was only nine minutes longer than scheduled. An analysis by another group in Switzerland reached the same conclusion.

On September 4, Bulgaria’s deputy prime minister stated clearly that there was no evidence the aircraft’s GPS had been jammed. The same day, the prime minister said there had been a temporary signal interruption but no jamming, while also signaling a willingness to request further investigation. The president went so far as to call the matter an “invented scandal.”

By September 5, the European Commission spokesperson had presented no new evidence and continued to direct reporters to the Bulgarian government’s statements. None of those statements, however, corroborated the claim of “blatant interference.” At that day’s midday briefing, the spokesperson cut off further questions from reporters, saying, “We’ve really said everything there is to say on this over the past week.”

As of this writing, the only confirmed fact is that the aircraft carrying President von der Leyen to Plovdiv, Bulgaria, experienced a temporary GPS signal interruption during landing. The interruption could have been caused by various technical factors, and no evidence of jamming has been detected. The pilots immediately switched to alternative navigation systems, and the aircraft landed without incident.

Bulgarian Prime Minister Rosen Zhelyazkov (Photo: Parlamentul Republicii Moldova / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0] )

It is true that GPS jamming is a serious problem in regions near Russia’s borders, affecting many aircraft across wide areas of Europe. The Bulgarian prime minister has acknowledged this. Such jamming is thought to be primarily caused by powerful Russian transmissions intended to disrupt the guidance systems of missiles and drones launched by Ukraine, according to reports. However, in this case, no evidence that such jamming actually occurred has been confirmed.

Intentional falsehoods

The initial Financial Times article was written by the paper’s Brussels bureau chief, Henry Foy. The claim in the article that the aircraft circled above the airport for an hour is false, and responsibility for it lies with him. He was on the flight himself and therefore would have known firsthand that no such thing occurred.

Foy also gave an exaggerated description of the incident on the paper’s podcast. He said: “On approach to Plovdiv, we lost altitude. We were in a kind of praying-for-a-landing situation and then we all realized that we were circling above the airport. We kept circling for a while. We were well past the scheduled time.” It is true that the landing happened well after the scheduled time. But that was because the takeoff was more than an hour late, not because the aircraft circled above the airport for an hour.

In the same podcast, Foy further claimed that the European Commission “confirmed our reporting and that they are treating this as a suspected case of Russian interference.” But this cannot be called “confirmation” in the journalistic sense. Both the “incident” he reported and the “suspicion of Russian involvement” were based on information provided by Commission officials in the first place. In other words, the origin of the claim and the entity that supposedly “confirmed” it were the same—hardly corroboration.

Moreover, the European Commission never publicly stated that the aircraft “landed using paper maps.” This false claim likely originated either with Foy himself or with an anonymous source within the Commission on whom he relied. Since the source is anonymous, it is impossible to verify the origin of the fabricated detail.

European Union flags outside the former headquarters of the Financial Times, UK (Photo: Metro Centric / Flickr [CC BY 2.0] )

The public claim that GPS jamming occurred and that Russian involvement was suspected was first announced at the European Commission’s press briefing on September 1. But as noted above, the Commission explicitly said it had not verified any evidence of jamming or Russian involvement, and had merely shared the “suspicions” communicated by the Bulgarian authorities. Those Bulgarian authorities, for their part, repeatedly denied—at least publicly—that jamming had occurred on this flight or that they suspected Russia. This strongly suggests that the “incident” may have been constructed by the European Commission in the first place.

If the incident had occurred as initially claimed, it would have been rational for the Commission—both to safeguard its president and to publicly flag an aggressive act by Russia—to pursue the matter further and release whatever evidence was available. Instead, it did not, and even cut off additional questions from reporters, suggesting that the incident did not happen as originally portrayed.

What was the motive?

We should briefly consider the motives of those involved. According to Foy’s own words, the purpose of the President’s visit to the EU’s eastern countries was “to draw attention to the threat posed by Russia and to press European governments to spend more on defense.” A dramatic incident in which the president’s own aircraft was subjected to GPS jamming would have provided a perfect, direct wake-up call to support that case from the Commission’s perspective.

According to Foy, Commission officials said that “frankly, this incident vindicates the trip. It shows Russia’s near-daily attempts to destabilize Eastern European countries,” and that these countries need “investment in defense and security, and even in civilian infrastructure and cybersecurity,” he said. At the September 1 press briefing, the Commission’s spokesperson similarly stated that the incident “further strengthens our unwavering resolve and supports our efforts to back Ukraine and strengthen Europe’s defense,” adding that it “underscores the urgency of this mission that the President is undertaking.” These remarks make it clear that the Commission regarded the “incident” and its timing as convenient.

President von der Leyen during a visit to Finland (Photo: FinnishGovernment / Flickr [CC BY 4.0] )

There remains a slight possibility that the Bulgarian authorities did detect some form of GPS jamming but chose not to acknowledge it publicly. Bulgarian officials appeared displeased with the negative fallout and reputational damage caused by the incident. On September 4, for example, the prime minister condemned “distorted interpretations” of the incident as efforts to undermine trust in Bulgarian institutions. Thus, the authorities may have had ample motive to emphasize that “nothing happened.” Still, it seems illogical that they would privately tell the European Commission they suspected “blatant Russian interference,” only to deny it entirely in public.

On the other hand, Foy’s own motives and level of involvement are harder to determine. Notably, he was the only journalist on the flight. When asked about this at a later press briefing, the Commission spokesperson avoided explaining why he alone accompanied the trip. Was this mere coincidence? Did Foy seize a chance for a scoop and add fictional elements to dramatize the story in line with the Commission’s claims? Did the Commission exploit the situation of having a single pool reporter to craft the narrative and control information? Or did Foy actively collude with the Commission and participate in exaggerating—or fabricating—the incident?

How the story spread

Following the Financial Times article, media outlets around the world reported the story in quick succession. Most of the coverage relied on indirect claims by the Commission’s spokesperson, and many leaned heavily on the FT’s original piece.

CNN ran it on September 1 as breaking news based solely on the Commission’s claim, reporting that the plane had been “targeted.” The New York Times published its own piece the same day, noting that it had sought comment from the Bulgarian authorities but received no response. Nevertheless, it published the story as the Bulgarian authorities “saw it that way” without any direct statements from them, relying entirely on the Commission spokesperson’s remarks. The lede was framed as hearsay: “Bulgarian authorities believe that Russia disrupted the navigation signal intended for a plane carrying Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, according to European officials.”

Party hosted by the Financial Times, UK (Photo: Financial Times / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0] )

Many other outlets showed no sign of attempting to confirm the story with the Bulgarian authorities at all, instead reproducing the Commission’s second-hand “suspicions” as-is. The UK’s Guardian and France’s Le Monde, among others, quoted directly from the FT article. Coverage by wire services such as Reuters further amplified the story globally. Nearly all headlines emphasized suspected Russian involvement.

Japanese media showed the same pattern. National dailies such as the Asahi Shimbun and Yomiuri Shimbun reported mainly on the basis of the FT article. The Nikkei ran a somewhat longer piece, referencing both the FT story and the Commission’s September 1 press briefing. Broadcasters such as NHK also reported the incident in a similar manner. Through dispatches by Jiji Press and Kyodo News, the story spread to regional newspapers and online media as well.

None of the outlets above displayed even a minimum of skepticism toward a story based solely on hearsay—despite the Commission having acknowledged from the outset that it had seen no evidence of GPS jamming or Russian involvement. Given the political benefits the Commission could reap from such claims, greater caution would have been warranted. None of these reports appears to have independently verified the GPS data, even though the data was already freely available online on September 1.

There were no corrections or retractions, and there was little follow-up after the Bulgarian authorities’ denials and the discrepancies with the GPS data became clear. Only a handful of outlets seriously questioned the official line. Notably among them were Euronews, Euractiv, Politico, Brussels Signal, and Off-Guardian.

European Commission spokesperson speaking at the regular press briefing (September 1) (Screenshot: European Union, 2025, CC BY 4.0)

Media complicity

The uncorroborated reporting on alleged GPS jamming against the aircraft carrying the European Commission president in Bulgaria is an example of how major media outlets become complicit in the spread of misinformation and disinformation. Such outlets often present themselves as “guardians of truth” or “bulwarks against mis- and disinformation,” yet in reality there are many cases where they fail to fulfill that role. Frequently, false claims flow from government officials to the media, and the media pass them on to the public without question.

This tendency becomes especially pronounced during armed conflicts—particularly when the outlet’s “home country” is directly involved or takes sides. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, there have been numerous instances where major media outlets repeated false accusations made by Western government officials against Russia. Notable examples include the fabricated claim in March 2022 that Russia was preparing to use chemical weapons in Ukraine, and the allegations widely reported in September of the same year that Russia was behind the sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipelines.

This is not to suggest that the Russian government should be absolved of responsibility for malicious acts it has actually committed. There are many actions by Russia that can be covered critically, for legitimate reasons and based on reliable evidence, without resorting to fabricated claims.

The coverage of von der Leyen’s landing in Plovdiv did not develop into sustained follow-up reporting; most outlets covered it only once. Nonetheless, the implications are far from small. The coverage heightened tensions in an already unstable wartime context, prompting even NATO’s chief to react strongly.

Moreover, this kind of reporting fuels the “demonization” of adversary states, reinforcing a narrative that portrays Russia as a habitual perpetrator of every malign act. The notion that Russia interfered with this flight was effectively accepted as “fact” almost immediately, and then reused to substantiate other alleged malign acts attributed to Russia. For instance, within ten days of the Bulgaria story, similar claims were reported in Sweden and Finland, with the Bulgaria incident being cited in those reports.

President von der Leyen visiting Bulgaria (Dati Bendo / European Union, 2025. EC – Audiovisual Service)

Tolerated falsehoods

Judging by the facts, the Financial Times was involved in fabricating at least part of the story. But what about the many other outlets that reported uncritically on the misinformation and disinformation related to this incident? They should have known that the Commission’s claims were unverified and based on hearsay. Did they place unconditional trust in the FT’s reputation as an authoritative outlet and believe what it said without question? Did they feel no need to verify, even though doing so would have been relatively easy? Did they view it as a “safe” allegation—an accusation against a state considered hostile by their own governments—that required no verification? Or did they see themselves as part of a public relations strategy against that adversary, willing to amplify low-credibility or even false claims if doing so served that purpose?

The longstanding pattern of journalists faithfully disseminating false information crafted by powerful government officials in ways that serve the interests of the state and its allies is well established. Even when such reporting is later shown to be false, the original articles are rarely corrected, and the reporters involved are seldom held to account. In some cases, they even appear to be rewarded.

Unfortunately, it seems unlikely that the major outlets which reported false or unsubstantiated claims in this case will issue retractions or corrections.

Note 1: GPS (Global Positioning System) is a satellite-based navigation system that provides position and time information anywhere on Earth. Through GPS, devices can determine their precise location, speed, and direction of travel.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

[4964]135phpgames: Best Online Casino & Slot in the Philippines. Quick Login, Easy Register, and Official App Download for Big Wins. Join 135phpgames, the premier online casino in the Philippines. Easy 135phpgames login & register for top 135phpgames slot action. Get the 135phpgames download app for big wins today! visit: 135phpgames

[9968]PHPopular Online Casino: Best Philippines Slots, Easy Login, Register & App Download Experience PHPopular Online Casino, the top choice for Philippines slots. Enjoy easy PHPopular login, register & app download. Play the best PHPopular slot games and win big today! visit: phpopular

[3830]w777: The Best Legit Online Casino in the Philippines – Top GCash Slots & Live Dealer Games Experience premier gaming at **w777**, the best online gambling site in the Philippines. As a top-rated **w777 legit casino GCash** players trust, we provide an elite selection of **online slots Philippines w777** enthusiasts love, plus immersive **w777 live dealer games PH**. Join the most reliable **w777 online casino Philippines** for secure transactions, fast payouts, and a world-class casino experience. visit: w777

[9242]Gperya Official Site: Philippines’ Top Online Slot | Fast Gperya Login, Register & App Download Experience the Philippines’ top online slot at the Gperya official site. Enjoy fast Gperya login, easy Gperya register, and secure Gperya app download. Join now! visit: gperya

[8848]68jl register|68jl login|68jl giris|68jl casino|68jl download Experience the ultimate Philippines online gaming at 68jl. Complete your 68jl register to enjoy premium 68jl casino games, secure 68jl login, and big wins. 68jl download the app today for the best mobile gambling experience! visit: 68jl

[8722]jljl88 slots|jljl88 casino|jljl88 giris|jljl88 register|jljl88 login Experience the ultimate gaming at jljl88 casino, the Philippines’ top destination for online players. Explore a massive variety of jljl88 slots, enjoy a seamless jljl88 login, and fast jljl88 register access. Join jljl88 giris today for exclusive bonuses and big wins! visit: jljl88

[1239]jljl77 register|jljl77 login|jljl77 download|jljl77 casino|jljl77 giris Experience the ultimate online gaming destination at jljl77 casino, the Philippines’ leading platform for slots and live dealer games. Secure your jljl77 login or complete your jljl77 register today to unlock exclusive bonuses. Enjoy seamless mobile gaming with the jljl77 download app and access our official jljl77 giris portal for a safe and thrilling gambling experience. visit: jljl77

[875]Jili16 Casino Philippines: Best Jili16 Slot Games. Quick Jili16 Login, Register & App Download for Big Wins! Join Jili16 Casino Philippines for the best Jili16 slot games! Quick Jili16 login & Jili16 register. Get the Jili16 download app for big wins at Jili16 casino today. visit: jili16

[4656]kkkjili Casino Philippines: Your Premier Destination for kkkjili Slot Games. Quick kkkjili Register, Easy kkkjili Login, and Fast kkkjili Download for the Ultimate Gaming Experience! Experience kkkjili Casino Philippines! Quick kkkjili register & easy kkkjili login for top kkkjili slot games. Fast kkkjili download for the ultimate gaming experience. Join now! visit: kkkjili

[440]Pin777 Official: Secure Login, Register & Pin777 Slot App Download for Philippines Players. Experience premium online gaming at Pin777 Official. Access your secure pin777 login, complete a fast pin777 register, and explore the best pin777 slot games today. Enhance your experience with the pin777 download app, designed specifically for Philippines players seeking safe and exciting casino action. visit: pin777