Around the world, one woman every two minutes dies from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth. Most of these deaths are preventable with appropriate, high-quality care. However, due to large differences in living conditions, governance, and health systems, the risk of becoming a mother remains high in many regions.

There have been major improvements over the past few decades. In 2000, the global maternal mortality ratio was about 328 per 100,000 live births; by 2023 it had fallen to around 197, a 40% decrease. This is a significant achievement, driven by expanded access to skilled midwives, improved emergency obstetric care, and the spread of simple yet effective tools such as drugs to prevent bleeding (※1) and clean delivery kits (※2).

However, since 2015 this downward trend has slowed. The reasons include cuts to funds allocated to health care, the destruction of medical facilities and services in conflict zones, and the diversion of resources following the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020.

This article examines global trends, the leading causes of maternal deaths, and the structural barriers that keep mortality rates stubbornly high. It also considers what is needed to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of “reducing the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.”

Antenatal checkup, Madagascar (Photo: Samy Rakotoniaina, MSH / Rawpixel [CC0 1.0])

目次

Why progress in reducing maternal mortality has stalled

The stagnation in reductions in maternal deaths has multiple causes. First, both national health budgets and international aid have tightened, and maternal health programs have often been among the first to be cut. This has led to reduced outreach services, unstable medicine supplies, and stalled development of basic infrastructure.

Second, armed conflict has inflicted immense harm on maternal health beyond the direct effects of violence. In Yemen, where conflict has continued since 2014, many medical facilities have been destroyed, supply chains cut, and health workers forced to flee conflict zones. The armed conflict that began in Sudan in 2023 similarly decimated maternal health systems, leaving many women to give birth without care. In Gaza, amid a situation in which Israel’s actions since 2023 are widely viewed as genocide, the health system has also suffered a devastating blow. In all of these cases, conflict-driven hunger has significantly pushed up maternal mortality.

Furthermore, the spread of COVID-19 in 2020 dramatically exacerbated already strained health systems. During the pandemic, many medical staff were mobilized for infection control, severely limiting routine obstetric services. Travel restrictions also prevented many pregnant women from reaching facilities in time.

These problems overlapped to worsen long-standing shortages of human resources and supplies worldwide. Even with the necessary knowledge and techniques, without professionally trained personnel and stable blood and medicine supply chains, it is difficult to ensure maternal care.

An ultrasound image showing a fetus (Photo: Nevit Dilmen / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Thus, the post-2015 stagnation is not due to a single factor but to a combination of funding and workforce shortages, armed conflict, and the impact of a novel pandemic. This shows up not only in the global numbers but also in widening gaps between countries and regions. In 2023, 92% of maternal deaths occurred in countries the World Bank classifies as low- and lower-middle-income.

This raises the question of why some countries have substantially reduced maternal deaths while others continue to face very high risks. The answer lies not only in the direct causes of maternal deaths but also in the social and institutional factors that underpin them.

Causes of maternal death

The main causes of maternal death are well known and, in many cases, preventable. Postpartum hemorrhage is one of the most common causes. In well-equipped facilities the bleeding can usually be stopped quickly, but in rural clinics without trained staff, basic surgical instruments, or essential drugs such as uterotonics, complications that should be treatable can become fatal within hours.

Infections are another major factor. They are typically triggered by unsanitary birth environments, prolonged labor, or inadequate postnatal care. In facilities without sterilized instruments or a stable supply of antibiotics, infection rates rise dramatically, placing mothers in serious danger.

(Photo: Arteida MjESHTRI / Freerange [Freerange license])

There are also less visible dangers. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, particularly preeclampsia (※3) and eclampsia (※4), can deteriorate rapidly and, if untreated, lead to organ failure or death. These conditions can be detected early through regular antenatal care, but in some low-income areas antenatal checkups are scarce or nonexistent.

Another challenge is obstructed labor. This occurs when the baby cannot pass through the birth canal due to issues such as malpresentation or a narrow pelvis. Without procedures such as cesarean section, mothers face serious risks including uterine rupture, massive hemorrhage, and severe infection. Such situations can be anticipated during antenatal care and managed during delivery with surgical interventions like cesarean section. However, in many rural or resource-limited areas, women must travel long distances to hospitals capable of surgery, a journey that can take hours. Some die on the way.

Unsafe abortion accounts for about 13% of maternal deaths worldwide. Where safe abortion services are legally restricted or inaccessible, women resort to dangerous methods, facing the risks of severe bleeding, infection, and injury.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that with high-quality antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, clean delivery environments, and rapid access to emergency obstetric care, up to 80% of maternal deaths could be averted. Yet guaranteeing such services and conditions is difficult in many low-income countries and regions. Inadequate facilities, shortages of medicines and equipment, transportation constraints, and limited human resources make it extremely challenging to carry out life-saving measures.

Antenatal checkup, Ethiopia (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Regional disparities

Understanding the causes of maternal death helps explain why some regions fare far worse than others. In many high-income countries, the maternal mortality ratio is under 5 per 100,000 live births. These countries have the resources to provide universal health coverage, comprehensive maternal and child health services, and high-quality facilities staffed by skilled professionals. Referral systems also function effectively, allowing women with complications to receive emergency care quickly.

In middle-income countries, gaps in maternal health are narrowing, but challenges remain. In Latin America, Peru and Brazil offer illustrative cases. Peru’s maternal mortality ratio fell from 102 per 100,000 live births in 2002 to 52 in 2023. This notable improvement is partly attributable to the universal health coverage system introduced in 2009. The share of people with any health insurance rose from 61% in 2009 to over 97% by 2023, with particularly marked gains in rural areas. In Brazil, the Unified Health System has promoted universal coverage, and maternal mortality fell from 140 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 65 in 2015, a decline of about 54%.

India has also made major progress. The maternal mortality ratio decreased by about 80% (from 658 to 80 per 100,000 live births), making it a global success story. However, significant regional disparities persist within the country. While urban areas have improved rapidly, mothers in rural areas continue to face high risks.

At the same time, countries such as Nigeria, Chad, South Sudan, and the Central African Republic remain at extremely high-risk levels of maternal mortality. In Nigeria and the Central African Republic, even as of 2020, maternal mortality exceeded 1,000 per 100,000 live births. In these countries, long-term political instability and armed conflict have severely disrupted health systems, damaged infrastructure on a wide scale, and driven out large numbers of skilled health workers. Beyond conflict-related factors, a widespread lack of financial resources also makes it difficult to provide maternal health services, especially in remote areas. With unstable funding and insufficient human resources, even when women deliver in facilities they often cannot receive effective treatment due to inadequate equipment and shortages of medicines.

This comparison makes clear that while reducing poverty and strengthening health systems can lower overall maternal mortality, without the allocation of more resources and policies targeting vulnerable groups, inequalities will persist between countries and within them.

Why inequalities persist

To understand why these inequalities remain entrenched, we need to look more deeply at the economic, social, and political factors behind them. These factors not only influence maternal mortality independently but often reinforce each other, causing risks to accumulate and creating environments where it is hard to sustain progress.

Poverty is one of the most fundamental barriers to safe maternal health. Women in low-income households often cannot afford antenatal checkups, skilled birth attendance, or emergency obstetric care. Transportation to facilities, consultation fees, and the cost of basic medical supplies frequently pose an excessive burden. Malnutrition, which is linked to poverty, weakens immune function, reduces resistance to complications, and increases the risk of anemia. Low educational attainment further exacerbates these risks, as women with less education tend to have difficulty recognizing warning signs during pregnancy and often lack knowledge about available services available to them.

Fragile health systems further amplify these economic barriers. In rural and remote areas of low-income countries, hospitals and clinics are in short supply and often suffer from resource constraints and chronic understaffing. Essential medicines, blood, and necessary equipment are often unavailable, and health workers have limited opportunities for continuing professional education. Moreover, health worker salaries are low and frequently paid late, undermining morale and retention and driving up turnover. Emergency transport systems, which are crucial for managing complications, are often limited or entirely absent. Because of these shortcomings, complications like hemorrhage, eclampsia, and obstructed labor—which could be managed in well-equipped facilities—can quickly become fatal in resource-poor settings.

Midwife training, Indonesia (Photo: Naval Surface Warriors / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Social and cultural barriers also exacerbate inequalities in maternal health. In some regions, women and their families are inclined to avoid facility-based births and choose home births with traditional birth attendants, due to distrust of hospitals, concerns over costs and transportation, or the belief that home birth aligns with tradition. While traditional birth attendants provide important support within communities, they often lack medical training and may be unable to manage complications, increasing the risk of maternal death.

In addition to resistance to facility births, broad gender norms also restrict women’s timely access to care. In some areas, women must obtain permission from husbands, elders, or family members before seeking medical attention. This requirement can lead to fatal delays, especially in obstetric emergencies. More fundamentally, entrenched gender inequality limits women’s decision-making power over health, affecting everything from choices about contraception and childbirth to whether they can go to a clinic.

Armed conflict and political instability make all of these challenges worse. Health infrastructure is destroyed, people are displaced, and skilled professionals leave for safer areas or abroad. Supply chains for medicines and equipment are disrupted, leaving facilities lacking even basic resources. Even in the absence of conflict, political instability undermines governance and policy continuity, hindering the consistency and coordination of maternal health programs.

Finally, volatility in aid funding hinders long-term improvements in maternal health. Many low-income countries depend heavily on international aid for mother-and-child health programs such as medicine procurement, midwife training, and the maintenance of primary health care facilities. When donors change priorities or cut funding, related services can collapse very quickly. For example, the sharp reduction in U.S. foreign aid in 2025 disrupted medical services in several countries. The U.S. budget cuts for low-income countries were said to have had “pandemic-like” effects on maternal mortality in already vulnerable regions. Such disruptions not only impede access to essential medical services but also erode trust in health systems, with serious consequences for maternal health.

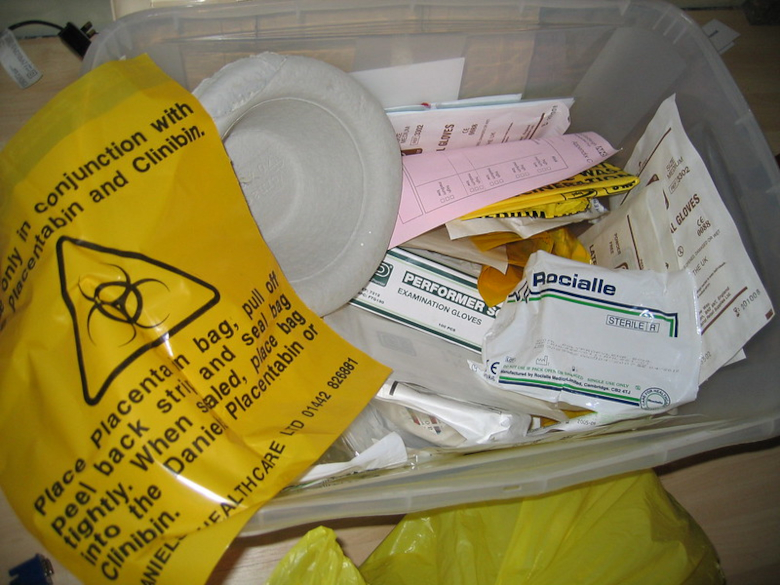

A home birth delivery kit (Photo: Dale Lane / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Efforts and success stories

While sustained improvements in maternal health require poverty reduction and conflict resolution, there is strong evidence that focused, context-specific interventions can substantially reduce maternal deaths. One of the most consistently successful approaches has been to train midwives and integrate them into local health systems. Research suggests that such efforts have reduced maternal deaths by as much as one-third in certain settings. In Ethiopia, a national program introduced in 2004 trained 30,000 health extension workers, bringing skilled care even to villages that had never had professional birth attendants. These midwives were trained not only in clinical techniques but also in community engagement, and are said to have helped overcome cultural barriers to facility births.

Low-cost, high-impact medical interventions are equally important. Clean delivery kits can be provided to pregnant women delivering at home and to traditional birth attendants; they include basic items such as sterilized razor blades, clean plastic sheets, and soap. These have been shown to substantially reduce infection risks during childbirth. Uterotonic drugs such as misoprostol can prevent and control postpartum hemorrhage, and broad-spectrum antibiotics can treat life-threatening infections. If these measures become widely available in resource-limited settings, the impact can be dramatic. The success of such efforts depends heavily on stable supply chains and the development of basic health systems, underscoring the need for steady funding and infrastructure.

Digital innovations are playing an increasingly important role. In rural Bangladesh, for example, mobile phone systems enable pregnant women to book antenatal appointments, receive automatic reminders, and request emergency transport. This simple yet effective mechanism has significantly increased timely access to care and reduced delays in receiving treatment.

Some countries have introduced integrated maternal health programs that bring these strategies together. In Rwanda, mobile technologies, including the RapidSMS system introduced in 2010, are combined with trained community health workers (CHWs) to monitor pregnancies, identify high-risk women, and coordinate rapid referrals to district hospitals. This model is considered one of the key factors behind Rwanda’s large decline in maternal mortality over the past two decades, with more than 9.3 million text messages sent by CHWs between 2012 and 2016.

A family who chose to deliver in a facility, Ethiopia (Photo: USAID Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

These cases show that when actions are tailored to local needs, receive sustained political support, and are backed by adequate funding, significant improvements are possible. However, scaling these successes remains difficult. Financial constraints, logistical barriers, and resistance to change in specific cultural contexts can hinder the spread of proven interventions. Related research also emphasizes that health system strengthening must proceed in parallel with building public trust, ensuring that services are not only geographically and financially accessible but also culturally acceptable and delivered without discrimination.

The way forward

The SDGs aim to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to below 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030. However, current trends indicate that achieving this goal without major transformation will be difficult.

The main reasons for the stalled progress lie in global poverty and inequality. At the individual level, poverty limits the ability to pay for antenatal care, transportation, and emergency care. At the national level, fragile public finances and insufficient tax revenues weaken health systems and hinder the provision of basic services. Maternal mortality is not merely a health indicator; it is also a key marker of resource scarcity and its unequal distribution.

Aid, international cooperation, and technological innovation are all important. But they cannot solve the root causes on their own. Reducing poverty and global inequality requires addressing broader structural challenges in international trade and financial systems and creating more equitable and sustainable economic and social environments.

※1 Drugs such as oxytocin and misoprostol help stimulate uterine contractions and prevent and manage postpartum hemorrhage.

※2 Delivery kit: A small kit containing the most basic clean items needed during birth, enabling delivery to take place as hygienically as possible. It includes basic items such as sterilized razor blades, a clean plastic sheet, and soap.

※3 Preeclampsia: Usually occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy and is characterized by high blood pressure and other organ dysfunction. It increases the risk of preterm birth and can also cause severe complications for the pregnant woman.

※4 A more severe progression of preeclampsia that can lead to cerebral hemorrhage, organ failure, and even death.

Writer: Lu Shan

Graphics: Lu Shan

面白い文章です。文章に書かれてる国は主にアフリカ国ですが、これらの国は経済発展が遅く、所得も低いです。国民の健康や生活のレベルを保つことができない。だからこそ、国連に保障されているというわけですね。しかし、これらの国々は所詮小国であるため、国際社会から注目されていないばかりか、国の状況などの事実が他国のメディアに報道されることもほとんどありません。いずれにせよ、アフリカの国々の経済発展をさせることには、国連の協力だけでなく、国際的な支援や援助の力が必要不可欠です。

医療において清潔は不可欠であることはもちろん、普段の生活においても、不可欠です。

ちょうど昨日私はマレーシアから帰ってきましたが、衛生面においていくらか目を疑う光景を目にしました。同じ国、都市にいても街の景色は全く異なるもので、まさに可視化されていました。直接的でなく間接的な影響に目をむけていたこの記事はこれからの問題解決にすごく役立つとおもいます。

SDGsの目標を今一度世界で認識され、掲げられることをねがいます。

先進国では、妊産婦の死亡はもはやあまり見られないケースだからこそ、この記事を通して、現在充実している医療サービスは当たり前のものではないことを再認識しました。

直接的な妊産婦死亡率の要因だけでなく、援助における資金の変動性といった間接的に大きな影響を与える要因についても詳しく述べられており、政府の単なる資金の削減が大きな問題にまで波及する問題がよくわかりました。

貧困の国や人々にどのように少しでも支援を行うことができるのか考えさせられる記事です

[4996]sbet77 slots|sbet77 app|sbet77 casino|sbet77 giris|sbet77 register Experience the ultimate gaming thrill at sbet77, the Philippines’ premier destination for online sbet77 casino action. Play a wide variety of sbet77 slots, download the official sbet77 app for mobile convenience, and enjoy seamless sbet77 giris access anytime. Don’t miss out—complete your sbet77 register today to claim exclusive bonuses and start winning big with the most trusted platform in the PH! visit: sbet77

[7013]jili777 app|jili777 casino|jili777 register|jili777 login|jili777 slots Experience the ultimate online gaming at Jili777 Casino, the Philippines’ premier destination for high-paying Jili777 slots and classic table games. Quick Jili777 register and seamless Jili777 login allow you to start winning instantly. Download the official Jili777 app today for a secure, mobile-optimized casino experience anytime, anywhere! visit: jili777

[3009]JilliAsia Casino: Best Online Slots in the Philippines. Easy Login, Register, and App Download. Experience the best online slots at JilliAsia Casino Philippines! Secure your JilliAsia login and register today to enjoy premium JilliAsia slot games. Fast JilliAsia app download available for the ultimate mobile gaming experience. Join now! visit: jilliasia

[1859]Experience the best lol646 online casino in the Philippines. Quick lol646 login, register, and lol646 app download to enjoy premium lol646 slot games today! Experience the best lol646 online casino in the Philippines! Enjoy a quick lol646 login and lol646 register process to play premium lol646 slot games. Get the lol646 app download today for a seamless mobile gaming experience and exclusive rewards! visit: lol646

[3955]Nice88: Best Philippines Casino Link for Slot Online, Easy Login, Register & App Download. Experience Nice88, the top Philippines casino link for the best nice88 slot online games. Enjoy a secure nice88 login, quick nice88 register, and seamless nice88 app download to start winning today. Your ultimate gaming destination awaits! visit: nice88

[4053]82jl Casino Online: The premier destination for 82jl slot games in the Philippines. Quick 82jl login, easy 82jl register, and official 82jl app download for the best gaming experience. Experience the best 82jl casino online in the Philippines. Get fast 82jl login, easy 82jl register, and official 82jl app download to play top 82jl slot games now! visit: 82jl

[9411]Experience the best online casino in the Philippines at 77ph1. Login or register now to play 77ph1 slots and live casino games. Secure 77ph1 app download available for the ultimate mobile gaming experience. Join 77ph1, the premier online casino in the Philippines. Quick 77ph1 login and register to play 77ph1 slots and live casino. Secure 77ph1 app download available! visit: 77ph1