Electric vehicles often have a cleaner image than gasoline cars. If we look only at driving, it is indeed true that no greenhouse gases are emitted from the vehicle. However, when we think more deeply, we see that this image is far from reality.

In GNV’s previously published article, “Are electric vehicles environmentally friendly?”, it pointed out environmental issues of electric vehicles from perspectives such as greenhouse gas emissions and environmental destruction accompanying the mining of raw materials.

In particular, cobalt, an indispensable mineral for lithium-ion batteries used in many electronic devices including electric vehicles, poses serious problems. Over 60% of the world’s cobalt is produced in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and this has led to issues such as environmental pollution, human rights violations, and exploitation. In addition, although the DRC has many other confirmed mineral resources besides cobalt, it has been pointed out that the rights to these abundant resources are one factor behind the conflict between the Congolese armed forces and the M23 rebel group, which has intensified since 2025.

This time, we want to focus on batteries in particular when considering electric vehicles. Specifically, to think about issues with the battery use cycle, pathways to improvement, and problems at the production stage, we introduce two articles about EV batteries from the news outlet “The Conversation”.

The first is “Batteries are the environmental Achilles heel of electric vehicles – unless we repair, reuse and recycle them” by Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian, Alex Stojcevski, and Saad Mekhilef, published May 24, 2023, and the second is “DRC is the world’s largest producer of cobalt – how control by local elites can shape the global battery industry” by Raphael Deberdt and Jessica DiCarlo, published September 4, 2024.

Through these two articles, let’s look at the problems caused by the batteries installed in increasingly widespread electric vehicles.

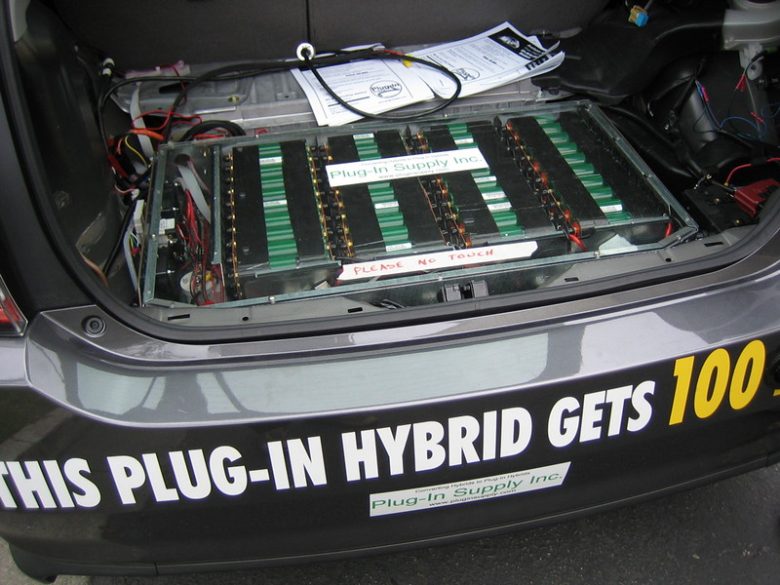

Behind the scenes of an electric vehicle while charging (Photo: Jean-Jacques Halans / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

目次

Batteries are the environmental Achilles’ heel of electric vehicles unless we can repair, reuse, and recycle them

《Translated article from The Conversation (The Conversation), by Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian, Alex Stojcevski, and Saad Mekhilef (Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian, Alex Stojcevski, Saad Mekhilef) (※1)》

Proponents of electric vehicles say EVs have lower ultimate CO2 emissions than fossil-fueled cars and fundamentally solve the energy problem. This claim sounds plausible, but when we dig deeper into EVs and look at how sustainable their components really are, questions arise. In fact, the battery that powers an EV is also the weak point in the claim that EVs are good for the environment.

The battery is the most expensive component in an EV. If a battery pack is damaged, defective, or simply old, it can render the vehicle it powers unusable sooner than expected. EV maker Tesla (Tesla) even manufactures a “unrepairable” “structural” battery pack.

Battery pack installed in a hybrid vehicle (Photo: Earthworm / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Producing these batteries requires resources that are becoming increasingly scarce and valuable, such as lithium and water, as well as other resources. Nevertheless, few batteries are designed to be easy to repair, reuse, or recycle. This has a major environmental impact—from the scarcity of materials extracted, to the water and energy used to make new batteries and cars, to the hazardous waste from discarded batteries.

In other words, the answer to the question “Are EVs really environmentally friendly?” can change depending on how we address the downsides related to batteries. Changes to how EV batteries are designed, manufactured, used, and recycled are urgent. By making these changes, we can solve the fossil-fuel emissions problem while minimizing other environmental harms.

If we’re going to act, now is the time

It’s important to address these issues while EVs still represent only a small share of the world’s vehicle fleet. Even in world-leading Norway, EVs make up only about 20% of the cars on the road. In Australia, of the 20 million registered vehicles, fewer than 100,000 are battery-powered.

But we are already facing new concerns regarding batteries. The performance of lithium batteries in EVs declines to 70–80% of full capacity in six to ten years, depending on the owner’s driving habits. At that point, the battery becomes largely unreliable as the vehicle’s primary power source. Repeated fast charging causes batteries to degrade even faster.

Globally, about 525,000 batteries will reach the end of their useful life as a vehicle power source by 2025. That number will surge to over a million by 2030.

Production line for electric-vehicle batteries (Photo: chris connors / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Use them as batteries after their EV life

However, the intrinsic lifespan of lithium batteries is about 20 years. This means that even when their life as in-vehicle batteries ends, they do not necessarily have to be discarded. Retired batteries have many other potential uses.

So how much capacity do retired batteries still have? As one example, a storage system repurposed from five Chevrolet Bolt batteries can meet two hours of peak energy demand for five homes. Tesla Model 3 batteries perform even better, with three times the energy capacity of the Chevrolet Bolt.

Even retired batteries can still deliver tremendous capacity. We should be making use of that.

And when a battery does reach the end of its useful life, it is possible to recover most of the raw materials used to make it. More than recover 95% of valuable metals like lithium, nickel, cobalt, and copper can be extracted. The European Union (EU) already mandates that EV batteries be at least 50% recyclable by weight, with plans to raise that to 65% by 2025.

A factory for repurposing used batteries (Photo: UNESCO-UNEVOC / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

However, the lack of standardization of battery packs is a challenge for battery recycling. Physical configurations, cell types, and cell chemistries vary wide.

The long supply chain that comes with reuse

The good news is that battery reuse is not just pie in the sky. Automaker Nissan is already doing it on Koshikijima in southwestern Japan. Batteries are recovered from EVs, their degradation is assessed, and then they are repurposed appropriately.

These batteries can be reused for solar power plants, home emergency power systems, and electric forklifts in warehouses. Research shows that reusing batteries in this way can keep them in effective service for another 10 to 15 years. This is a significant leap toward reducing environmental impacts.

So who benefits from this approach? The answer includes many actors.

First, EV owners can benefit immediately if their used batteries can be sold at a good price.

Over the longer term, the range of beneficiaries expands significantly. Households can enjoy more stable and cheaper energy by charging storage batteries during off-peak times in preparation for peak-rate periods. A Portuguese initiative showed that using repurposed EV batteries in this way cut electricity bills by 40%.

Battery reuse is also good news for the environment. Studies indicate that reducing demand for new batteries in this way can cut greenhouse gas emissions from battery manufacturing by as much as 56%.

Giving EV batteries a second life and then recycling their materials afterward offers many benefits. Considering the scale of the potential economic and environmental gains and the numerous jobs such work would create, batteries may generate more value in their second-life reuse than during their time inside an EV.

DRC, the world’s largest producer of cobalt: How control by local elites is shaping the global battery industry

《Translated article from The Conversation (The Conversation), by Raphael Deberdt and Jessica DiCarlo ( Raphael Deberdt, Jessica DiCarlo ) (※2)》

Rich in mineral resources, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is often portrayed as a victim of exploitation by China, the United States, and Europe in the competition to secure minerals essential for the energy transition.

However, our research shows that as the largest producer of cobalt by far, the DRC wields influence in shaping the global cobalt market. Cobalt is a critical metal that helps suppress battery overheating. It is indispensable in manufacturing electric vehicles.

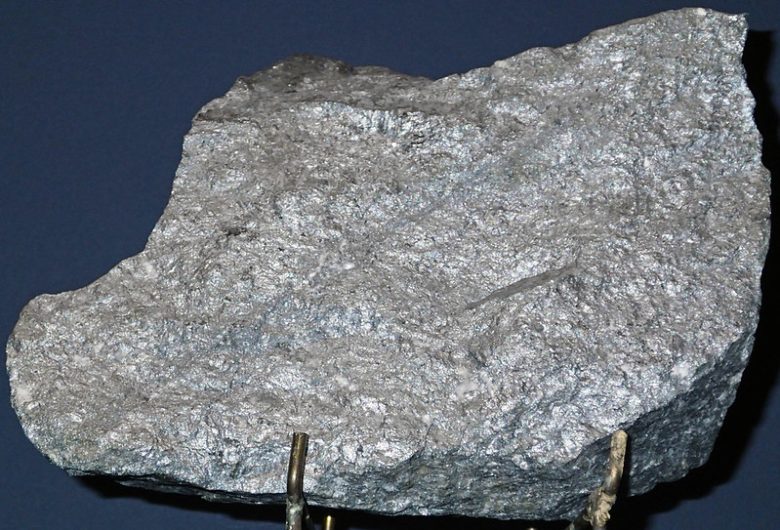

Cobaltite, an important cobalt ore (Photo: James St. John / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Research in China and the DRC, including our study, revealed how governments in countries often seen as peripheral, like the DRC, can influence and sometimes play decisive roles in global industries.

Our findings are based on months of fieldwork in cobalt mines worked by artisanal miners (※3) and in industrialized cobalt mines, as well as in Chinese infrastructure projects. We also examined local media and government documents and studied legal and administrative decisions.

We found that the DRC government exercises strong control at both national and local levels. Decisions on mining policy by politicians in the capital Kinshasa and in mining regions like Kolwezi have repercussions across the global battery supply chain. For example, as the country that produces 70% of the world’s cobalt, the DRC has leverage over the global EV battery supply chain.

Nevertheless, the DRC has not used this influence for the benefit of its people. An estimated 74% of the country’s population continues to live in poverty. While a portion of mining revenues flows to the government, day-to-day life has barely improved for communities living around the mines. Many people continue to face poverty, pollution, and dangerous working conditions in and around mining sites.

Cobalt processing by China

Cobalt was first mined in the DRC in 1914, during the Belgian colonial period that lasted from 1885 to 1960, when many of the country’s valuable resources were plundered by Belgium.

Today, the DRC’s cobalt is exported to China. It accounts for lithium-ion batteries (rechargeable batteries) cathode feedstock at a share of 65% of cobalt refined worldwide. China is also the world’s largest producer of these batteries and dominates the EV industry. In 2023, one in five cars sold worldwide was an EV.

In China, the cobalt refining and battery manufacturing industries have grown rapidly over the past two decades. Chinese companies have made large investments in developing advanced processing technologies and large-scale production facilities.

A large number of mobile phone batteries sold in a shop in China (Photo: Windell Oskay / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

These factories convert unprocessed cobalt from the DRC into high-purity cobalt compounds to be incorporated into battery cathodes. Chinese companies such as Huayou Cobalt, CATL, and BYD lead cobalt refining and battery production, supplying products to the global EV market.

DRC’s influence over the cobalt industry

While Chinese mining companies, both private and state-owned, control the DRC’s vast cobalt deposits, our research concludes that the DRC can exercise significant influence over the broader industry.

For example, in 2022 when the DRC government halted exports from the largest Chinese-owned cobalt mine due to financial issues, roughly 10% of global cobalt production temporarily stopped.

Looking closer, when Fifi Masuka Saïni became governor of cobalt-rich Lualaba Province in the DRC, she seized trucks transporting cobalt to pressure Chinese companies that had benefited under the previous governor and President Kabila’s inner circle. As a result, Chinese operators re-established relations with the new provincial government.

Cobalt after washing and processing (Photo: Electronics Watch / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Local politics can also cause production slowdowns. For example, China’s cobalt industry sources some cobalt from artisanal miners, but in 2021 the DRC central government canceled contracts for purchases from sites worked by artisanal miners, despite provincial approval. Kinshasa pushed to establish a company to purchase all artisanal cobalt produced within the province, but local interests clashed with this approach. Chinese operators found themselves caught in the middle. Lengthy negotiations between Chinese and Congolese sides followed, and the position of Chinese companies became unstable, shifting with the political will of both Kinshasa and Kolwezi.

The government has also exerted leverage over minerals by pushing for better terms in mining contracts and for more domestic processing. For example, in 2018 it declared cobalt a “strategic” resource and tripled export taxes.

Benefits don’t reach local people

However, even though the DRC can wield influence over this sector, people who should be benefiting from the wealth generated by the cobalt industry, such as artisanal miners, are not receiving their share.

Currently, in the southeastern DRC there are at least 67 cobalt mines where artisanal miners work. About 150,000 artisanal miners are employed in this industry and face dangerous conditions.

Artisanal miners can be buried in collapsing tunnels or exposed to radioactive gases.

Miners working in dangerous conditions for extremely low wages (Photo: The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

They are also exploited, with up to 50% of artisanal miners’ income collected by miners’ cooperatives, which are often controlled by powerful politicians. It is estimated that artisanal miners sites in the DRC employ about 40,000 children under dangerous conditions.

Local realities matter

Our research shows that the transition to clean energy technologies is not merely a matter of scientific and technological innovation or great-power politics. Even local elections in towns near African mines can sway global supply chains.

The transition to renewable energy is global. Countries such as the United States and China need to treat producers like the DRC not as mere suppliers of raw materials—which can harm local communities during the transition—but as partners in the global energy transition. That requires supporting locally rooted supply chains, increasing domestic value addition including further processing of cobalt in the DRC, and fairer contracts.

Especially as the EV revolution accelerates, we must listen to the often-overlooked voices and interests of mineral-producing regions like the DRC. By making these less visible power dynamics clear, this research offers useful insights for policymakers, companies, and stakeholders working toward a cleaner energy future.

※1 This article is a translation of The Conversation piece by Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian (Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian), Alex Stojcevski (Alex Stojcevski), and Saad Mekhilef (Saad Mekhilef), “Batteries are the environmental Achilles heel of electric vehicles – unless we repair, reuse and recycle them.” We would like to take this opportunity to thank The Conversation and the three authors for providing the article.

※2 This article is a translation of The Conversation piece by Raphael Deberdt (Raphael Deberdt) and Jessica DiCarlo (Jessica DiCarlo), “DRC is the world’s largest producer of cobalt – how control by local elites can shape the global battery industry.” We would like to take this opportunity to thank The Conversation and the two authors for providing the article.

※3 Artisanal miners are workers who mine as individuals or as part of small-scale enterprises rather than as employees of companies. It is currently estimated that there are 45 million artisanal miners worldwide, comprising roughly 90% of the labor force in global mining. However, artisanal mining also causes problems such as dangerous working environments, child labor, and poverty, and improvements are needed.

Writers: Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian, Alex Stojcevski, Saad Mekhilef, Raphael Deberdt, Jessica DiCarlo

Translator: Seita Morimoto

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/id/register?ref=UM6SMJM3