FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) or FGC (Female Genital Cutting) is a term that refers to the excision or injury of female genitalia. It has no health benefits and is in fact harmful, yet it has been practiced as a traditional custom in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

At GNV in the past, in the article “The steep decline in female genital mutilation (FGM): what’s behind it?,” we examined the situation of FGM in Africa. Also, in “2018 top 10 hidden world news,” the news that FGM among girls under 14 in East Africa plummeted over 20 years from 1995 to 2016 was selected as number 8.

Because FGM was declining sharply as of 2018, it was thought it would continue to decrease. However, in recent years there have been reports that it is increasing again in some places. New research findings have also emerged on the risk of death related to FGM.

This time at GNV, we introduce two articles on female genital mutilation (FGM) from the news outlet “The Conversation (The Conversation).” The first is “Female genital mutilation is on the rise in Africa: disturbing new trends are driving up the numbers” by Tamsin Bradley, dated May 12, 2025.

The second is “New study finds: female genital mutilation is a leading cause of death for girls where it’s practised” by Heather D. Flowe, Arpita Ghosh, and James Rockey, published on February 6, 2025.

Through these two articles, we delve into the current state and harms of FGM, and the path toward eradication.

A woman with her arm around the best friend who stopped her FGM: Ethiopia (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Female genital mutilation is on the rise in Africa: disturbing new trends are driving up the numbers

《Translated article from The Conversation (The Conversation), by Tamsin Bradley (Tamsin Bradley ) (Note 1)》

Salamatu Jalloh was a promising 13-year-old girl. But in January 2023, her mutilated body, wrapped in pink and blue burial cloth, was found on the earthen floor of a village in northwestern Sierra Leone.

The cause of death for Salamatu and two other girls was loss of blood after taking part in the female initiation rite performed by the secret society known as Bondo. The ceremony began with excitement and anticipation as a rare chance in rural communities to celebrate girls, and it continued for weeks. But at its core was the violent act of cutting and removing the girls’ external genitalia.

Their tragic deaths were highlighted in UNICEF’s latest report on female genital mutilation. According to the UN agency, an estimated 230 million girls and women alive today have survived FGM, but live with its devastating consequences.

Most procedures take place in African countries, totaling 144 million.

Despite campaigns to end this practice, compared to eight years ago there are 30 million more women and girls worldwide who have been subjected to this form of torture.

As an applied social anthropologist who has long studied women and violence, I have researched this form of abuse and why it persists for over 20 years. Some countries are making progress in reducing abuse. Others are stalling or backsliding due to ideological shifts and instability or conflict.

UNICEF estimates that to eliminate this abuse by 2030, the pace of decline needs to be increased by a factor of 27-fold.

Understanding the trends is a starting point for ending FGM. Some of the new trends are alarming: conservative backlash against efforts to stop FGM; a rise in “secret procedures” that are difficult to track; and a shift toward “less severe” forms. The growing “medicalization” of procedures performed by health professionals is also concerning.

Photo used for the International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM: Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: MONUSCO Photos / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Reasons for FGM

There are various types of cutting. The most severe form, infibulation, stitches together the cut edges of the labia to achieve a smoothness that is considered beautiful. The vagina must be opened again during sexual intercourse or childbirth.

Every year, more than 500,000 girls worldwide undergo this extreme form of vaginal cutting.

Many who support FGM believe it maintains cleanliness, increases girls’ marriage prospects, preserves virginity, prevents “female promiscuity,” and thus protects family honor. Some also believe it enhances fertility and prevents stillbirth.

In reality, FGM has no health benefits and causes numerous harms to girls and women. There are immediate risks of complications such as shock, bleeding, tetanus, sepsis, urinary retention, genital ulceration, and damage to adjacent genital tissue. Long-term effects include increased risk of maternal morbidity, recurrent bladder and urinary tract infections, cysts, infertility, and psychological and sexual harm.

FGM in African countries

The countries with the highest prevalence are Somalia (99%), Guinea (95%), and Djibouti (90%).

Kenya has undergone remarkable change over the past half-century. Where FGM was once widespread, most of the country has now abandoned the practice.

However, among Somali communities concentrated in northeastern Kenya, there has been little change, and the practice remains almost universal.

Somalia and Sudan face the challenge of addressing widespread FGM amid conflict and population growth.

Ethiopia has made consistent progress, but climate change, disease, and food insecurity are making it difficult to sustain these successes.

The fragility of progress is clear.

Conservative backlash and compliance

There are several troubling trends making it even harder to end this practice.

First is a conservative backlash. Religious leaders in The Gambia have called on lawmakers to repeal the 2015 law banning FGM. They reacted after three women in the northern village of Bakadaji were found guilty in 2023 of cutting eight girls—the first major convictions under the law. The World Health Organization (WHO) warns that repeal in The Gambia could embolden other countries to ignore their obligations to protect these rights.

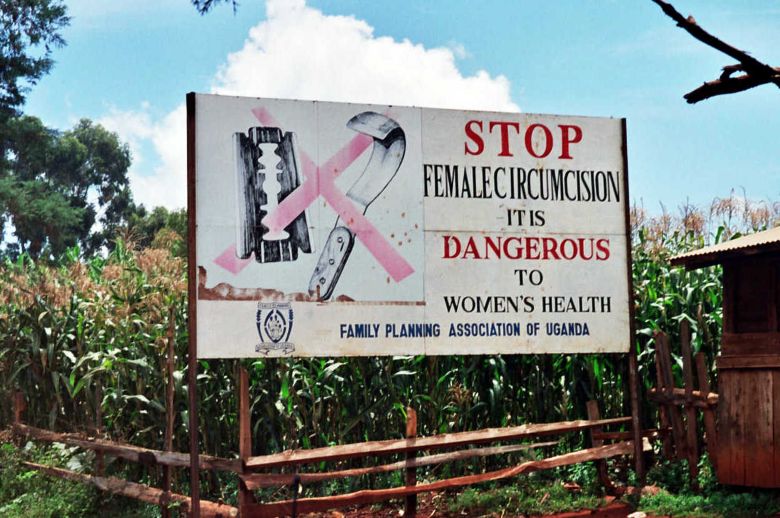

Road sign from a campaign opposing FGM: Uganda (Photo: Amnon s / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Second is the rise of secret procedures. In countries where the practice is banned, procedures are often hidden. To avoid detection, girls are also being cut at younger ages. This makes it difficult to obtain accurate prevalence rates for FGM.

Third is a shift toward “less severe” forms, one of which is clitoridectomy. In countries such as Sudan and Somalia, because the vagina is not sewn shut, many people consider this to be harmless. Proponents argue that this does not constitute FGM.

Fourth is “medicalized” procedures performed by trained individuals such as doctors, nurses, and midwives. Because these are perceived as safer, some consider them legitimate. They are increasingly performed in public or private clinics, pharmacies, and homes.

Destabilization and erosion of rights

About 4 in 10 girls and women who have undergone FGM live in countries affected by conflict and fragility. Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Sudan have the largest numbers of girls and women subjected to FGM among conflict-affected countries.

Armed conflict and the devastating impacts of climate change rapidly deepen poverty, generate mass displacement, and push people off their land and livelihoods. Research shows that when families face dire choices in extreme poverty, girls’ rights can be sidelined research.

Marriage practices such as bride price commodify girls, meaning daughters can be sold when families are stripped of every other asset. As a marker of a girl’s virginity, FGM becomes essential.

Progress toward ending this horrific abuse needs to accelerate. Understanding shifting trends is the first step.

New study finds: female genital mutilation is a leading cause of death for girls where it’s practised

《Translated article from The Conversation (The Conversation), by Heather D. Flowe (Heather D. Flowe ), Arpita Ghosh (Arpita Ghosh), and James Rockey (James Rocky) (Note 2)》

Female genital mutilation (FGM/C) is a deeply rooted cultural practice that affects about 200 million women and girls. It is practised in at least 25 countries in Africa, parts of the Middle East and Asia, and among migrant communities worldwide.

It is a harmful traditional practice involving the cutting or injury of female genital tissue. It is often “justified” by cultural beliefs about controlling women’s sexuality and marriage prospects. FGM/C causes immediate and lifelong physical and psychological harm to girls and women, including intense pain, complications in childbirth, infections, and trauma.

A midwifery class at a vocational school working to eradicate FGM: Darfur, Sudan (Photo: UNAMID / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

We combined expertise in economics and gender-based violence to investigate excess mortality (avoidable deaths) due to FGM/C. Our new study https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10432559/ reveals a grim reality: FGM/C is one of the leading causes of death among girls and young women in countries where FGM/C is practised, with the potential to cause death through hemorrhage, infection, shock, and obstructed labor risks.

We estimate that about 44,000 people die each year across the 15 countries we studied. This is equivalent to one girl or young woman dying every 12 minutes.

In the countries studied, this constitutes a more significant cause of death than any infectious disease other than malaria, respiratory infections, and tuberculosis. In other words, it is a larger cause of death than many familiar health threats to girls and young women in these countries, such as HIV/AIDS, measles, and meningitis.

Previous research shows that FGM/C causes severe pain, bleeding, and infection. But tracking deaths directly caused by the practice has until now been almost impossible. One reason is that in many countries where FGM/C occurs it is illegal, and it generally takes place in non-clinical settings without medical oversight.

Countries where the crisis is most severe

The practice is particularly widespread in several African countries. In Guinea, 97% of women and girls have undergone FGM/C; in Mali, 83%; and in Sierra Leone, 90%. Egypt’s high prevalence, with 87% of women and girls having undergone FGM/C, is a reminder that FGM/C is not confined to sub-Saharan Africa.

We analyzed data from 15 African countries where there is comprehensive and definitive information on FGM/C prevalence. In other words, the data are comprehensive and reliable, and widely accepted for research, policymaking, and advocacy to combat FGM/C.

We developed a new approach to overcome previous data gaps. For 15 countries from 1990 to 2020, we matched data on the share of girls who underwent FGM/C at different ages with age-specific mortality rates. The age at which FGM is carried out varies greatly by country. In Nigeria, 93% of cases occur among girls under 5. In Sierra Leone, most girls undergo the procedure between ages 10 and 14.

Because health conditions vary by place and time, and even from year to year in the same place, we accounted for these differences. This allowed us to see whether more girls were dying at the ages when FGM/C is typically carried out in each country.

For example, in Chad, 11.2% of girls ages 0–4 have undergone FGM/C, compared to 57.2% at ages 5–9 and 30% at ages 10–14. We were able to observe how mortality rates change across these age groups compared to countries with different patterns of FGM.

This careful statistical approach enabled us to identify excess mortality associated with FGM while controlling for other factors that could affect child mortality.

Photo used at the Girl Summit held in the UK in 2014: an Ethiopian parent and child (Photo: DFID – UK Department for International Development / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Striking findings

Our analysis indicates that when the share of girls who underwent FGM in an age group rises by 50 percentage points, the mortality rate for that age group increases by 0.1 percentage points. This may seem small, but applied to the total populations of affected countries, it translates to tens of thousands of preventable deaths per year.

While armed conflict in Africa caused about 48,000 battle-related deaths annually between 1995 and 2015, our study suggests FGM/C leads to about 44,000 deaths per year. This underscores that FGM is one of the most serious public health challenges facing African countries.

Beyond the numbers

These statistics represent real lives lost. Most FGM/C procedures are performed without anesthesia, proper medical supervision, or sterile instruments. Resulting complications include severe hemorrhage, infection, and shock. Even when not immediately fatal, they can lead to long-term health problems and increased risks during childbirth.

The impact goes beyond physical health. Survivors often face psychological trauma and social difficulties. In many communities, FGM/C is deeply embedded in cultural traditions and tied to marriage prospects, making it difficult for families to resist the pressure to continue.

An urgent crisis

FGM/C is not only a human rights violation but also a public health crisis requiring urgent attention. In some areas, communities are beginning to abandon FGM/C, and there has been progress. At the same time, our research indicates that current efforts to combat FGM/C need to be dramatically scaled up.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have worsened the situation due to its broad social, economic, and health-system impacts. The United Nations estimates the pandemic may have added 2 million preventable FGM/C cases. Based on our mortality estimates, that would mean roughly an additional 4,000 deaths across the 15 countries we studied.

The way forward

Ending FGM/C requires a multifaceted approach. Legal reform is crucial, and in 5 of the 28 countries where FGM is most commonly practised, it remains legal. But legislation alone is not enough. Changing deeply rooted cultural beliefs and practices requires community engagement, education, and support for grassroots organizations.

Research has shown that information campaigns and community-led initiatives can be effective. For example, in Egypt, studies report that increased access to SNS and the use of educational films presenting different perspectives on FGM/C have contributed to reductions in its prevalence.

Boys and girls learning about the consequences of FGM: Burkina Faso (Photo: DFID – UK Department for International Development / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Most importantly, communities where FGM/C is practised must be engaged. Our research underscores that this is not merely about changing a tradition—it is about saving lives. With every year of delay, tens of thousands of preventable deaths are added.

Our findings suggest that ending FGM/C should be treated as an urgent priority on par with major infectious disease control. The lives of millions of girls and young women depend on the eradication of FGM/C.

Note 1: This article is a translation of the piece “Female genital mutilation is on the rise in Africa: disturbing new trends are driving up the numbers” by Tamsin Bradley (Tamsin Bradley ) at The Conversation (The Conversation). We would like to express our gratitude here to The Conversation and to the author, Bradley, for providing the article.

Note 2: This article is a translation of the piece “Female genital mutilation is a leading cause of death for girls where it’s practised – new study” by Heather D. Flowe (Heather D. Flowe), Arpita Ghosh (Arpita Ghosh), and James Rockey (James Rocky) at The Conversation (The Conversation). We would like to express our gratitude here to The Conversation and to the authors Flowe, Ghosh, and Rockey for providing the article.

0 Comments