The World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are the most important development and financial institutions in today’s global economy. However, since their establishment in 1944, their activities and track records have sparked intense debate. Both the WB and the IMF are accused of causing adverse social and environmental impacts in the countries and regions where they operate, and many experts and scholars are calling for structural and governance reforms. Some voices even call for abolishing the WB and the IMF, or replacing them with other institutions.

At the 2024 Annual Meetings of the IMF and World Bank Group held in Washington, D.C., IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva highlighted two areas where governments can exercise discretion and set priorities: (1) rebuilding fiscal buffers as debt reduction and preparation for the next financial crisis, and (2) reforms for growth that improve employment, tax revenues, fiscal space, and debt sustainability. She signaled to the world that the IMF can do better. Meanwhile, World Bank President Ajay Banga expressed his determination to “build a better bank” by optimizing the Bank’s operations, focusing more on economic impact, and boosting its lending capacity.

Both suggested reforms during their tenures, but neither message came as a major surprise. The WB and IMF appear set to continue business as usual.

“End poverty.” World Bank headquarters (Photo: World Bank / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

About the World Bank and the IMF

Founded in 1944, these 2 institutions were originally intended to foster recovery from World War II and to promote international economic cooperation for global development. The WB was designated as the lending institution to finance postwar reconstruction plans. However, as the World Bank president stated in 2023, the Bank’s focus has expanded beyond economic reconstruction to “creating a world free of poverty on a livable planet,” and it has come to prioritize development.

Meanwhile, the IMF’s role was to promote stability in international payments and exchange rates, and to maintain resources for providing short-term loans to member countries in financial crises. Over the past several decades, the IMF has not only lent to member states but has also stood with them as a financial steward, offering advice—albeit only as guidance, though highly influential—on how to respond to economic crises. As of February 2025, the IMF’s outstanding credit amounts to about US$110.4 billion.

Yet the record of the WB and the IMF shows that, contrary to their stated mandates and missions, both institutions are associated with underdevelopment and human hardship. They have been consistently criticized for policy missteps and strategies that, rather than solving poverty and economic distress in low-income countries, intentionally—or contrary to their original intent—worsen conditions. How, then, do the WB and the IMF exacerbate global poverty? The main causes lie in their organizational structures and operating mechanisms. These features are said to leave the institutions unwilling or unmotivated to tackle poverty and related sociopolitical problems, leading them to act in ways that prioritize the interests of dominant members.

Former World Bank President David Malpass speaking at the World Bank–IMF Joint Development Committee (Photo: World Bank / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

A human-rights-free zone

Because of their legal structures, both institutions consider economic factors exclusively, and rights stipulated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights—such as the rights to an adequate standard of living, freedom from hunger, the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, and education—are largely irrelevant to their activities. In a 2015 report, the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty described the World Bank as a “human-rights-free zone.”

The report explains that the World Bank’s legal framework includes a “political prohibition” clause (Article 4(10)) that prevents the integration of human rights into projects and programs. At the same time, political considerations may influence this point. Western countries sometimes use human-rights criticisms to withhold development loans to certain states, while borrowing countries are wary of interference in their domestic affairs on human-rights grounds, the report notes. As a result, although several initiatives have been introduced to align the World Bank with a rights-based approach to development, the Bank’s consideration of human rights remains in a dire state.

In recent years, the World Bank has been criticized for allowing or indirectly causing the forced relocation of millions of marginalized people and Indigenous communities as a result of financing mega-infrastructure projects such as dams, power plants, and highways. A major problem is that while the Bank extends enormous loans, it does not manage the evictions triggered by these projects, nor does it provide alternative housing options for those displaced. Without reform of its legal framework, the Bank will continue to treat human rights “more like a pesky contagion than universal values and obligations,” the report warns.

Construction of Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam, financed by the World Bank, for which human-rights concerns have been raised (Photo: Sosh19632 / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

The IMF does not state that it can ignore human rights due to a “political prohibition”; rather, it simply claims that human rights fall outside its obligations. The IMF sees itself as a purely technical and financial organization and prohibits political considerations in its work. In 2003, a group of experts drafted the “Tilburg Guiding Principles on World Bank, IMF and Human Rights” to define the institutions’ human-rights obligations, but more than 20 years on, neither the IMF nor the World Bank has recognized those obligations.

A capital-weighted organizational structure

The undemocratic governance structure of the World Bank and the IMF also influences their policy choices and recommendations. At Bretton Woods, where both institutions were founded, a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement” was reached that the World Bank president would be an American and the IMF managing director a European. Since then, the leadership selection at the WB and the IMF has never deviated from this arrangement, suggesting that U.S. and European interests have always been reflected in both institutions.

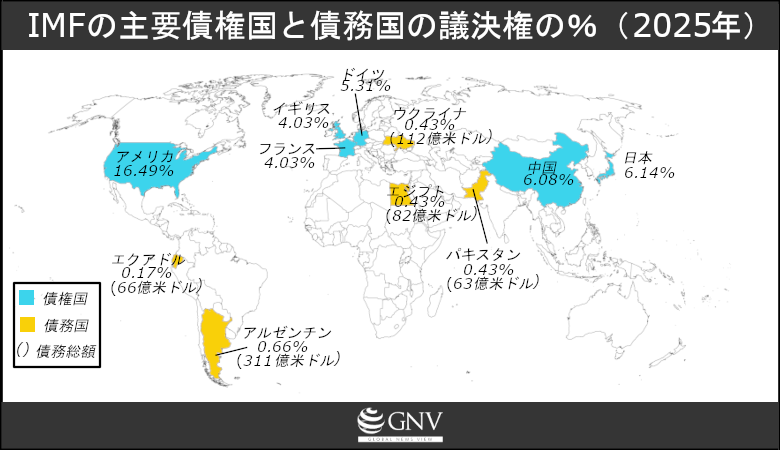

Furthermore, unlike the United Nations General Assembly, which grants one vote to each of its 193 member states, the World Bank and the IMF allocate voting power based on members’ shares and subscriptions. Under this system, the United States, Japan, and European countries dominate the distribution of voting rights, while low-income countries are underrepresented. For example, 173 IMF member states—most of them low-income countries with substantial borrowing—are allocated on average just 0.19% of the vote per country (※1). Many of the largest debtor countries also have low voting shares. Some observers describe this power imbalance as a form of apartheid or minority rule. Taking populations into account, for each vote assigned to people in high-income countries, people in low-income countries receive only one-eighth of a vote. This structural bias in decision-making effectively negates the role of low-income countries in the international economic order.

The actions and objectives of the World Bank and the IMF have increasingly come to be seen as prioritizing the interests of dominant high-income members—namely, expanding global market access—over addressing poverty. Former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz has argued that the four-step template program (privatization, capital-market liberalization, market-based pricing, and free trade) that the WB and IMF prescribe as a cure-all for economies prioritizes opening borrowing countries’ markets to facilitate the entry of foreign capital and the takeover of certain domestic productive sectors by creditor countries and multinational corporations, rather than actually resolving the economic problems at hand.

Stiglitz further notes that such strategies are accompanied by austerity measures said to help reduce fiscal deficits, restore economic stability, and service arrears. For the public already suffering from economic pressure, austerity means losing access to welfare benefits. It is therefore easy to imagine “IMF riots” being sparked by the IMF’s “prescriptions.”

Some scholars further speculate that such social unrest may itself be part of the World Bank and IMF strategy to further advance the dominant members’ agendas. Social unrest triggers capital flight, pushes some industries into bankruptcy, and depresses asset prices. This situation is considered favorable for foreign investors, who can then buy up assets at low prices.

Recent research has identified two notable tendencies of the IMF: the Fund is less likely to demand austerity from borrowers with strong diplomatic and trade ties to the West, and more likely to demand austerity from borrowers that accept large amounts of Western foreign direct investment.

Responses to financial crises

The results of these tendencies can be seen in the World Bank and IMF responses to financial crises. The IMF followed its template during the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s and the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, with devastating consequences.

IMF Executive Board (Photo: International Monetary Fund / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In the 1980s, Latin American countries saw their debts balloon to a total of US$442.5 billion by 1987, and the resulting defaults triggered a financial crisis. The crisis brought severe regional recession, including trade stagnation, massive job losses, and inflation fluctuating to dangerously high levels of 149% (1981-89) and 218% (1990-93). The World Bank and IMF stepped in. Between 1983 and 84, the IMF provided a total of US$9 billion and the World Bank lent US$3 billion to bail out defaulting Latin American countries.

But these rescues came with problems. Both institutions imposed conditions in the form of “structural adjustment programs” (SAPs) that required borrowers to undertake fiscal austerity, liberalize markets and investment, and aggressively pursue privatization. U.S. economist Jeffrey Sachs sharply and succinctly criticized this approach: “Since 1982, the basic strategy of the IMF and the creditor governments … has been to ensure that the commercial banks are able to collect interest payments in full.”

These externally imposed policies drew heavy criticism because they failed to consider people suffering under economic burdens who needed government subsidies for relief. The results were devastating. Due to the debt crisis and its management, more than 500,000 children under five were dying each year in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America in the late 1980s, according to grim estimates.

In the 1990s, the IMF followed its template in responding to the Asian financial crisis. It provided US$36 billion to governments in Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand to support reforms, while pressuring them to liberalize and implement austerity. Indonesia complied by abolishing food and fuel subsidies for the poor. As a result, massive riots erupted in Jakarta. A 2002 report claims that “1,200 people were burned to death and 8,500 buildings and vehicles were destroyed” in the unrest.

Just over a decade later, in 2010, the IMF faced Europe’s financial crisis. Greece’s US$310 billion debt crisis threatened European financial stability. To save Greece, the IMF broke some of its rules and pushed through the largest rescue package in its history, US$125 billion. In doing so, the IMF ignored its rule of not providing packages to countries clearly unable to repay and allowed outsiders to determine the package’s conditions.

Protests against austerity in Greece (2010) (Photo: Εφημερίδα ΠΡΙΝ / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The Brazilian executive director’s comment below shows what may have underpinned the IMF’s position: “The risks of the program are immeasurable…… it could be seen not as a rescue of Greece’s public finances with harsh adjustment, but as a bailout of Greece’s private creditors, namely European financial institutions.” This corresponds to Sachs’s earlier criticism that the IMF was working for the interests of major Western commercial banks.

Further adding irony, countries in economic crisis and social unrest have no say in how they are rescued. Institutionally, they cannot oppose those who control and command the capital of the World Bank and the IMF.

Who bears the burden of debt?

According to a recent Human Rights Watch report, IMF lending programs approved between 2020 and 2023 continue to rely on the Fund’s traditional approach of “mandating cuts in public spending and raising taxes in ways that disproportionately burden low-income people.” Another NGO, Oxfam, further stated that “for every $1 the IMF encouraged poor countries to spend on public goods, it has told them to cut four times as much through austerity.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, data from 1986 to 2012 show that IMF lending “contributes to trapping more people in cycles of poverty.” Sub-Saharan Africa is emblematic. One reason is the massive job losses and inflation that accompany IMF conditional lending. For example, the World Bank and IMF requirement to privatize state-owned enterprises in Ghana between 1984 and 1999 led to the loss of more than 150,000 jobs. And after SAPs were implemented in the region from 1981 to 2001, the number of people living in poverty on less than US$1 a day doubled from 164 million to 316 million.

Experts also point out the tragedy that the poorest sub-Saharan African countries transferred about US$229 billion to high-income Western countries as debt payments between 1980 and 2004. And the tragedy continues in low-income countries. In 2023, global public debt reached a record US$97 trillion. Other shocking figures abound: 54 low-income countries spend more than 10% of their income on debt service, and 48 low-income countries with a population of 3.3 billion spend more on interest payments than on education and health.

In 2024 the world watched Kenya grapple with IMF conditional lending. To address a liquidity crunch, Kenya received an additional US$941 million from the IMF, bringing its outstanding balance to US$3 billion and making it the Fund’s 6th-largest debtor, becoming one. With nearly US$13 billion in outstanding debt, Kenya is also among the IMF’s largest debtor countries.

In 2022, at the IMF’s request, the Kenyan government abolished subsidies for maize flour and fuel, and the following year doubled the value-added tax on fuel from 8% to 16%. Local residents opposed to harsh austerity measures organized large protests in the capital, Nairobi.

Glass at Kenya’s parliament smashed by protesters opposing a tax-hike plan (2024) (Photo: Abner Mbaka / Shutterstock.com)

The IMF’s conditions for Kenya recall the strategies adopted to address the crises of the 1980s and 1990s. In 2015, the IMF admitted that it had “underestimated the damage austerity would do to Greece.” Seeing this affirmation of austerity, it appears that the IMF still has not learned lessons from financial crises outside Europe. Kenya may face a situation akin to Latin America in the 1980s or the Asian financial crisis in the 1990s.

Immunity and lack of accountability

Another issue with the WB and the IMF is their institutional immunity even when they cause harm. Like other international organizations, the World Bank and IMF enjoy immunity from legal proceedings, as stipulated in the IBRD Articles, Article VII, and the IMF Articles, Article IX. As a result, private individuals are deprived of the right to bring claims before domestic or international courts and cannot seek meaningful remedies for wrongs done to them. This absolute immunity was challenged before the U.S. Supreme Court in 2019, but both institutions continue to uphold absolute immunity from suit.

Furthermore, the lack of internal accountability mechanisms has fostered a culture of impunity. Since 2010, both the World Bank and the IMF have been plagued by cases involving senior executives. In 2011, Dominique Strauss-Kahn of the IMF was arrested for sexually assaulting a hotel maid in New York. A former World Bank economist—now the president of Costa Rica—was accused of sexual harassment while repeatedly being promoted during more than 20 years at the Bank. Such sexual misconduct has persisted at the World Bank for years and is widely concerning. A recent report noted that “one in 4 women at the Bank has experienced sexual harassment.”

Even major scandals may leave top leaders unscathed. Current IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva kept her post after being embroiled in a 2017 incident in which World Bank data were allegedly manipulated to favor China, making a report more attractive to investors. Another IMF head, Christine Lagarde, received a conviction in 2016 for negligence and misuse of public funds, yet likewise kept her post and escaped punishment.

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva (Photo: International Monetary Fund / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

These incidents have damaged the reputation of the World Bank and the IMF as international development institutions, cast doubt on their credibility as authoritative sources of data and policy advice, and revealed their vulnerability to capture by personal interests and powerful lobbying groups.

Unless substantive reforms are made to the World Bank’s and IMF’s structural and operational mechanisms, their other pledges will remain mere words without effect. The WB and IMF will continue business as usual, worsening poverty in low-income countries and aggravating social and environmental conditions.

※1 If there were one country, one vote, about 0.58% of voting rights would be allocated per country.

Writer: Darren Mangado

Translation: Seita Morimoto

Graphics: MIKI Yuna

0 Comments