In 2024, the average temperature at Earth’s surface, including land and oceans, exceeded the pre-industrial level by 1.55°C (Note 1), making it the warmest year on record. This points to a grave situation that threatens the long-term Paris Agreement goal adopted in 2015 to keep warming “well below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C.”

But is the Japanese media covering this issue with the seriousness it deserves? Judging from the volume and content of reporting on climate change, many questions remain about how the issue is being framed. GNV has been examining the history of Japan’s climate-related coverage and, building on our analyses from 2021 and 2023, we expand our long-term analysis of reporting on climate change to track trends in 2023 and 2024.

A parent and child forced to flee due to severe drought (Ethiopia) (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Current state and background of climate change

As noted above, 2024 became the warmest year on record, with the global average surface temperature (land and oceans) rising 1.55°C above the pre-industrial level. It has also become clear that ocean warming played an important role (Note 2) in this record heat. In 2024, both global sea surface temperature and ocean heat content in the upper 2,000 m reached record highs, and from 2023 to 2024, ocean heat content increased by an amount approximately 140 times the world’s total electricity generation in 2023. Some said this ocean warming was due to the temporary sea temperature rise from the 2023 El Niño event (Note 3), but the limited recovery even after El Niño ended suggests that the effects of rising greenhouse gases cannot be ignored. Ocean warming appears to raise air temperatures not only through heat release from the ocean but also by increasing atmospheric water vapor, itself a greenhouse gas.

The extreme weather events driven by warming of the atmosphere and oceans have been devastating. In 2023, ocean warming coincided with heatwaves, triggering the second-largest mass coral bleaching event on record and causing mass die-offs of marine animals. Global sea level reached record highs due to thermal expansion and ice melt; in 2024, on the small Panamanian island of Gardi Sugdub, 300 families were forced to relocate because of sea-level rise. Beyond warming, ocean acidification has also reached extreme levels.

In Libya in 2023, climate change increased the intensity of heavy rain by up to 50%; after torrential downpours, three dams failed and more than 3,400 people lost their lives. In the Amazon River Basin, below-average rainfall since mid-2023 meant climate change made meteorological drought about 10 times more likely and agricultural drought about 30 times more likely. Canada suffered the most extreme wildfires on record. These are just a few examples of heatwaves, heavy rainfall, drought, and fires influenced by climate change. Health impacts are also severe, with rising mortality and medical costs. In India in 2024, an unprecedentedly long heatwave pushed temperatures to 50°C in some areas, and at least 60 people died of heat-related illnesses. From 1999 to 2023, heat-related mortality rose by 117%.

Drought-damaged maize (Zambia) (Photo: UNDP Climate / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Greenhouse gas emissions show no sign of slowing

We noted that the effects of rising greenhouse gases cannot be ignored in the warming of the atmosphere and oceans, and this is grounded in the fact that greenhouse gases have indeed increased. Global greenhouse gas emissions in 2023 rose 1.3% from 2022 to a record high. Considering that the average annual growth from 2010 to 2019 before COVID-19 was 0.8%, the pace of increase is clearly accelerating. In 2024, concentrations of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide all hit record highs. CO2 in particular is surging, and the growth rate of methane emissions is also accelerating.

Behind these record greenhouse gas emissions lies record fossil fuel consumption. In the 2023 global energy mix, fossil fuels—oil, coal, and natural gas—accounted for 82%, and consumption (Note 4) hit a record high.

Looking at the regional breakdown of emissions, G20 members account for 77% of global greenhouse gas emissions, while the African Union (55 countries) accounts for 6% and the least developed countries (45 countries) just 3%. Major emitters include China, the United States, India, and the EU (27 countries). Between 2022 and 2023, the U.S. and EU cut emissions by 1.4% and 7.5% respectively, while China and India increased theirs by 5.2% and 6.1%. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported in 2023 that, to limit warming to within 1.5°C as per the Paris Agreement, global greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced by 43% from 2019 levels by 2030. There is a large gap between this 43% target and actual reductions.

One factor propping up greenhouse gas emissions is subsidies for fossil fuels. In 2023, total government subsidies for fossil fuels reached USD 1.1 trillion. Although down from USD 1.6 trillion in 2022, this is still above the average of the past 15 years and remains a major obstacle to climate action. See our previous article for details. Fossil fuel–related investment in 2024 also exceeded USD 1 trillion, driven by increased activity by national oil companies in the Middle East and Asia. Meanwhile, investment in renewables reached USD 2 trillion, meaning the bulk of energy investment is flowing into clean energy—but not yet fast enough to rapidly reduce fossil fuel dependence. To meet climate goals, it is essential to reform fossil fuel subsidies, scale up investment in renewables, and accelerate innovation in low-emission technologies.

A coal mining site, a fossil fuel (Australia) (Photo: D. Sewell via Lock the Gate Alliance / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Global responses to climate change seen in 2023 and 2024

Despite ongoing issues with the investments and subsidies that encourage fossil fuel consumption—the main driver behind emissions—in 2023 and 2024, what steps did the world take to reduce greenhouse gases? And what broader climate action was undertaken? The key to understanding this lies in the differing positions of high-income countries, emerging economies, low-income countries, small island developing states (SIDS), and oil-producing nations.

SIDS in the South Pacific, including Vanuatu—among the countries most acutely affected by sea-level rise and natural disasters—raised calls for climate justice (Note 5). In March 2023, it was decided to request an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on states’ legal obligations regarding climate change. In the EU, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) (Note 6) entered into force in March 2023, introducing a system to levy charges on imports reflecting the difference in carbon prices. In India, the “National Green Hydrogen Mission” was launched in August 2023 to promote green hydrogen (Note 7) for decarbonization and expanded renewable energy use.

In September, the first-ever Africa Climate Summit was held in Kenya, where African countries led discussions on climate action. The summit called on high-income countries to provide climate finance and reform the financial system, but also drew criticism for the outsized influence of Western nations and a tilt toward investments in renewables and carbon markets led by the West, while sidelining Africa’s own priorities such as compensation for climate-induced disasters. Later that month, the SDG Summit and the Climate Ambition Summit took place at UN headquarters in New York, featuring “trailblazers” and “doers” with credible actions and policies to accelerate decarbonization and climate justice.

From November 30 to December 13, 2023, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) in the oil-producing United Arab Emirates (UAE). COP28 (Note 8) conducted the first Global Stocktake (GST) (Note 9), revealing shortfalls against emission reduction targets. Countries are to submit new Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by 2025, and goals were set to triple renewable energy deployment and double energy efficiency by 2030 (Note 10). The COP outcome also, for the first time, included references to fossil fuels in the final agreement. This came against a backdrop of thousands of organizations amplifying calls for a fossil fuel “phase-out” through coordinated advocacy.

However, stronger language calling for a “phase-out” of fossil fuels was avoided, with ambiguous phrases such as “phase-down” and “transition,” and a call to end “inefficient fossil fuel subsidies,” which could create loopholes, prevailing. COP28 reportedly included 2,456 fossil fuel lobbyists, whose efforts are said to have influenced negotiations in the industry’s interests. A “Loss and Damage Fund” was established to compensate for losses borne by low-income countries and SIDS, but the fund falls far short of the USD 580 billion expected by 2030.

Group photo at COP29 (Azerbaijan) (Photo: President of Azerbaijan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0])

In January 2024, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) announced it had approved a record USD 10 billion in climate finance in 2023, and in September set a target to allocate 50% of annual lending to climate-related projects by 2030. In August, the EU’s Nature Restoration Law entered into force, aiming to restore ecosystems by 2050 and implement restoration measures on more than 20% of land and sea by 2030. Through nature restoration, the EU seeks climate change mitigation and adaptation (Note 11). In October, the 16th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP16) was held, recognizing the interplay between climate change and the biodiversity crisis. Discussions strengthened frameworks to pursue climate mitigation and adaptation together with biodiversity conservation, including ocean-based climate solutions, data sharing, expanding marine protected areas, and achieving “30 by 30” (protecting 30% of land and sea by 2030). Funding shortfalls were also identified as a challenge.

At the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) held from November 11 to 24, 2024 (Note 12), the New Collective Quantified Goal on climate finance (NCQG) was agreed, tripling finance to low-income countries and mobilizing USD 1.3 trillion annually by 2035. Of this, USD 300 billion is to be contributed by high-income countries, with the remainder relying on voluntary contributions from emerging economies, private finance, and multilateral development banks. This prompted strong criticism from emerging economies, low-income countries, and SIDS over the limited contributions by high-income nations and the uncertainty of funding sources. In addition, investment was prioritized for renewables and low-carbon technologies, while mechanisms to fund loss and damage saw little progress, and there was criticism from low-income countries and SIDS of 批判 favoring emerging economies. Further criticism erupted because discussions on the transition away from fossil fuels did not advance and references were removed from the final text. The host country Azerbaijan’s plan to increase gas production and the hardline stance of oil-dependent countries also hampered climate action. The U.S. presidential election result, with President Donald Trump—who had campaigned on withdrawing from the Paris Agreement—winning, was seen as introducing uncertainty to climate negotiations. The gap between high- and low-income countries widened, making improved transparency in finance and clarity on the transition away from fossil fuels key challenges going forward.

After COP29, in December the United Kingdom joined the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which promotes sustainable trade and imposes environmental protection obligations. Other international bodies including APEC, ASEAN, the International Energy Agency (IEA), and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also made climate-related decisions and announcements from their respective standpoints.

Europe’s largest coal-fired power plant (Poland) (Photo: Roman Ranniew / Flickr [Public domain])

Long-term analysis of reporting that references climate coverage since the 1980s

We have reviewed the state of climate change and global responses in 2023 and 2024. In both years, the indicators of climate change reached record levels, and various climate disasters, impacts on health and crop yields, and sea-level rise became major threats. Meanwhile, greenhouse gas emissions—the main cause—show a large gap compared with the targeted cuts. High-income countries are somewhat proactive in investing in renewables and decarbonization technologies, but remain reluctant to compensate for loss and damage borne by low-income countries and SIDS. Overall, there are issues with transparency in finance and concreteness of action plans, raising concerns about backsliding of climate ambition.

How much of this was reported in Japan? Following the methodology in the notes (Note 13), we tallied the number of articles in three major newspapers (Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun) from 1984 to 2024 that mention climate change, global warming, or COP, whether domestic or international coverage. Increases in 1997, 2008, and 2021 are analyzed in detail in a previous article. What stands out this time is the decline in coverage in 2023 and 2024. Reporting on the Russia–Ukraine war since 2022 and the Israel–Palestine war since 2023 spiked, and in 2024 the U.S. presidential election also dominated media attention. Perhaps due to the lack of ambitious decisions on the international stage, the number of articles mentioning climate change stagnated. Questions remain as coverage remained low—even after surpassing the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal—falling below 1997 levels and decreasing relative to 2021.

Medium-term analysis of climate reporting in 2023 and 2024

As noted, new facts underscored the severity of 2023 and 2024, increasing the urgency of climate action, yet the volume of coverage mentioning climate change was not particularly high. What, then, did the coverage focus on?

Across the three major newspapers in 2023 and 2024, the number of articles dealing with climate change (Note 14) spiked in November when COP was held. Looking more closely, over the two years 2023–2024, the share of climate-related articles that primarily focused on COP was very high: 56.7% in Yomiuri, 32.5% in Mainichi, and 28.9% in Asahi. Keywords frequently mentioned alongside COP (≥15% of COP-mentioning articles) in 2023 were “fossil fuels,” “temperature,” “greenhouse gases,” “renewable energy,” and the host country “UAE,” reflecting COP28’s main themes. By contrast, “loss and damage” accounted for only about 4.5% of COP28 mentions. Some outlets did not mention the specific “Global Stocktake,” and none of the three directly referred to “lobbying.”

In 2024, mentions of “developed countries” rose 57% and mentions of “finance” rose 54% compared to 2023—even as overall COP mentions fell—suggesting a growing recognition of high-income countries’ role, including in relation to COP28 outcomes. Focusing on COP29, mentions of “finance” were already 31% higher than in 2023, reflecting the focus on finance at COP29. Mentions of “President Trump” rose from five combined in 2023 to more than 50 in 2024. Meanwhile, mentions of fossil fuels fell about 42%, temperature about 30%, and “loss and damage” appeared in only one outlet—indicating limited coverage of issues that did not advance sufficiently at COP29, with few efforts to fill the gaps through critical or prescriptive reporting. There was no reporting using the specific name “New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG),” and only one outlet mentioned the USD 1.3 trillion target, though all three mentioned the USD 300 billion contribution. Even among COPs, coverage of CBD COP16 was just 14% and 30% of COP28 and COP29 mentions respectively.

In COP-related coverage, mentions of “greenhouse gases,” “temperature,” “renewable energy,” “fossil fuels,” and “developing countries” each exceeded 180 across the three outlets over two years, reflecting strong interest in emission reductions and achieving the 1.5°C goal. On the other hand, compared to mentions of “government” and “companies,” there were fewer references to the “private sector” and “citizens,” and attention to “emerging economies” was limited compared to “developing countries” and “developed countries,” suggesting insufficient coverage of civil society’s role and the responsibilities of emerging economies. The focus of discussion skewed toward “support” rather than “compensation,” with few low-income country perspectives. Mentions of concrete challenges such as “subsidies,” “climate justice,” and “lobbying” were limited, indicating a generally narrow scope relative to the breadth of issues.

Mentions of climate/warming agreements or developments outside COP were limited overall. Reporting on the UN Water Conference and India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission was nearly nonexistent, and coverage of the Africa Climate Summit and the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism was confined to certain outlets. There were also imbalances in coverage of international frameworks such as the 2023 Climate Ambition Summit, the ICJ resolution, the SDG Summit, the UK’s accession to CPTPP, and ADB’s expansion of climate-related lending—while APEC, ASEAN, the IEA, and the IPCC received a certain amount of attention.

Such imbalances likely reflect editorial interests and choice of sources, confirming that perspectives on global climate action trends are limited.

Summary

Climate change is an extremely serious problem requiring urgent action. Global warming is accelerating, and its impacts—record-breaking temperatures, frequent extreme weather events, and rising sea levels—are becoming a reality. To meet the targets of the Paris Agreement, countries must act swiftly and boldly. Yet dependence on fossil fuels remains high, and greenhouse gas emissions are at record levels. Although low-income countries and SIDS bear the brunt of warming, inequities persist. There are signs of waning ambition in some high-income countries, underscoring the need for greater transparency and accountability in finance, and more concrete implementation plans.

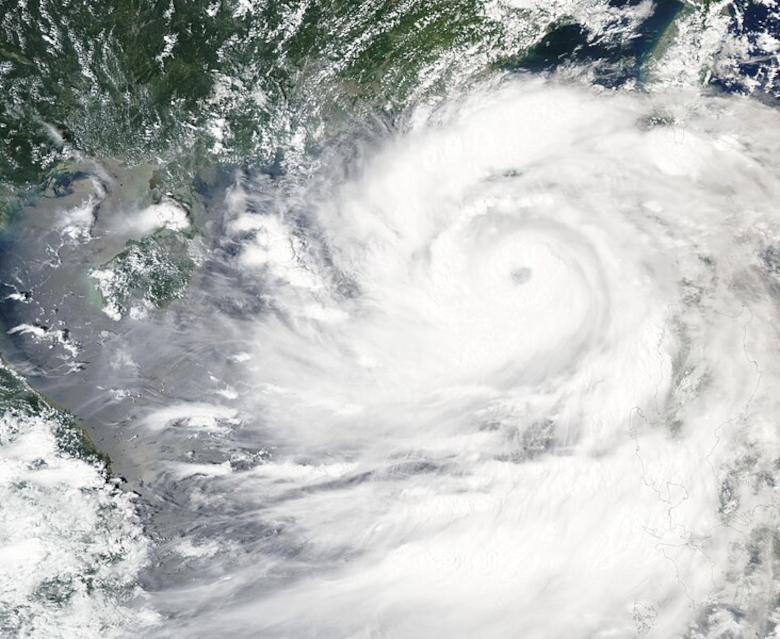

Typhoon Yagi intensifying over the South China Sea (Photo: MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Climate reporting in Japan remains centered on the Japanese perspective. There are major imbalances in coverage of international frameworks and events, and limited references to specific decisions. When it comes to financial targets, there is a tendency to emphasize “support” and “investment” rather than “compensation” for low-income countries. Although terms like “problems” or “failures” appear in COP coverage, concrete and detailed references are mostly absent or couched in indirect language. More broadly, reporting focuses on institutional actors such as governments and companies, with less attention to damages borne by citizens or the role of citizens themselves.

Based on the above analysis, there is room for improvement in the three major Japanese outlets to provide richer information from more diverse and in-depth perspectives when conveying the worsening of climate change and the progress of countermeasures.

Note 1: The figure of 1.55°C is a composite calculation from six sources: the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), the Japan Meteorological Agency, NASA, NOAA, and the UK Met Office/University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit (HadCRUT), and Berkeley Earth. These six temperature assessments use different methodologies and range from 1.46°C to 1.62°C.

Note 2: Global warming occurs when incoming solar radiation and outgoing terrestrial infrared radiation fall out of balance. As greenhouse gases that absorb infrared radiation increase, less infrared escapes to space. The absorbed infrared energy warms the Earth system, and the oceans store about 90% of this excess heat. Consequently, while ocean uptake had moderated rapid surface and atmospheric warming, it also raised sea surface temperatures, making the impact of greenhouse gases clearer when examining sea surface temperature and ocean heat content.

Note 3: The El Niño phenomenon is when sea surface temperatures from near the international date line in the equatorial Pacific to the South American coast are higher than average for about a year. It occurs when the trade winds weaken, allowing warm water normally piled up in the west to spread eastward while upwelling of cold water diminishes. El Niño can trigger abnormal weather worldwide.

Note 4: The breakdown of emission sources shows the power sector largest at 26.4%, followed by transport (14.7%), agriculture and industry (both 11.4%). International aviation surged as it recovered from the pandemic. Fuel production (oil and gas infrastructure, coal mining), road transport, and energy-related industries also rose rapidly in 2023.

Note 5: A concept aimed at fairly distributing the impacts and burdens of climate change and protecting the rights of those in vulnerable positions.

Note 6: A system that imposes a cost on products imported into the EU based on emissions during production, applying a carbon price comparable to that on EU products to prevent inflows of cheap, high-emission goods, limit carbon leakage, and strengthen climate action.

Note 7: Hydrogen produced by electrolysis of water using renewable energy.

Note 8: In addition to what is described in the main text, COP28 featured discussions on the importance of conserving nature and ecosystems, support for methane emission reductions, establishment of the “UAE Framework” as a Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), and financial commitments for regenerative agriculture and climate/food innovation under the first COP declaration dedicated to insurance—the “COP28 UAE Declaration.” Other outcomes included adoption of carbon market rules covering approaches to governing CO2 removal and the development of 100 indicators to measure progress toward the sectoral goals of the COP28 UAE Framework.

Note 9: The Global Stocktake is an opportunity to evaluate progress toward the Paris Agreement’s goals and indicate the future direction of climate action.

Note 10: Expectations were also placed on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, but there are concerns that overreliance could hinder fundamental solutions to climate change.

Note 11: Mitigation includes strengthening carbon sinks through ecosystem restoration and promoting a bioeconomy; adaptation includes reducing natural disaster risks such as floods and droughts via ecosystem restoration, conserving water resources, and cooling cities through green spaces, among other measures.

Note 12: In addition to what is described in the main text, carbon market rules covering approaches to governing CO2 removal were adopted, and 100 indicators were developed to measure progress toward the sectoral goals of the COP28 UAE Framework.

Note 13: We used the Asahi Shimbun online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross Search,” the Mainichi Shimbun online database “Maisaku,” and the Yomiuri Shimbun online database “Yomidas Rekishikan.” We counted all articles containing “COP” or “climate change” or “global warming” in the headline or body, published in the morning or evening editions (all pages) of the Tokyo-headquartered Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri from January 1984 to December 2024.

Note 14: For article counts, we used the Asahi Shimbun online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross Search,” the Mainichi Shimbun online database “Maisaku,” and the Yomiuri Shimbun online database “Yomidas Rekishikan.” We counted all articles with “COP” or “climate change” or “global warming” in the headline, published in the morning or evening editions of Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri from January 2023 to December 2024.

Writer: Kanako Kinoshita

Graphics: Virgil Hawkins

いつも素晴らしい調査と情報提供をありがとうございます。

1980年代からの気候報道に言及する報道の長期分析(※13)と2023年と2024年の大手新聞3社での気候変動問題を扱った記事の数(※14)の2つのグラフが本日から見れなくなってしまっているようなのですが、原因は分かりますでしょうか?有益な情報のため、ご対応いただけますと幸いです。

気候変動問題は決して数年前に突如起こった問題というわけではなく、かなり前から対処すべき世界全体の課題の一つであった。にもかかわらず、各国が各々の利害を重視し、一体となった対策を取らなかった結果が現在の危機的な状況に繋がっていると感じた。何年にもわたり、ほとんどの国の気候変動問題に対する姿勢が変化していないようにも感じられ、交渉力の比較的小さい島嶼国ばかりが危機感を抱いているように見える。

いつも、詳しい情報をありがとうございます。

多くの国が低所得国への温暖化対策について話す時、支援/climate resilience, invensting という言葉が使われるのが、私としても気になっていました。

それぞれの人々が自身の持つ環境に対しての加害性を知る必要があると思います。