In recent years, the rise of synthetic cannabinoids, commonly known as “Spice” (Note 1), has increased public health risks. The situation is particularly critical in Central Europe. On the street corners of Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia—known as the Visegrád Four (V4)—it is not uncommon to see people in states of euphoria and confusion caused by a range of drug-induced side effects. This situation has worsened in recent years.

These substances were initially sold as a legal alternative to cannabis. However, it has become clear that synthetic substances are far more dangerous than natural narcotics. They are causing not only physical harm to individuals but also a deterioration of public safety across entire communities. Because synthetic cannabinoids are inexpensive to produce and easy to obtain, the number of users has surged, disproportionately harming socially marginalized groups, including economically disadvantaged youth, people experiencing homelessness, and the Roma minority community.

Synthetic cannabinoids (Photo: Courtesy photo, Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall / Wikimedia Commons [public domain])

目次

Global drug trends

For centuries, naturally occurring drugs have played some role in human history. They have been used to ease pain, for recreation, and as economic instruments. The cultivation of marijuana dates back to the 1600s. Because of its strong fiber structure, marijuana was primarily used for rope-making; medicinal use has been recorded since the 1850s. Similarly, the coca plant, harvested in the Andes for at least 800 years, served both as a stimulant and as an alternative currency in the Inca Empire.

However, from the 19th to the 20th century, the synthesis of these plants began. Scientists modified natural substances to enhance their effects for medical and military purposes. Drugs like cocaine and stimulants were used during the world wars to increase soldiers’ stamina and reduce fear, and morphine was administered to armies as a painkiller. Military use continued after World War II; during the Vietnam War, the U.S. military widely used amphetamines. These developments paved the way for modern drug use, including the spread of synthetic substances. Recreational drug use expanded significantly in the latter half of the 20th century.

Synthetic cannabinoids

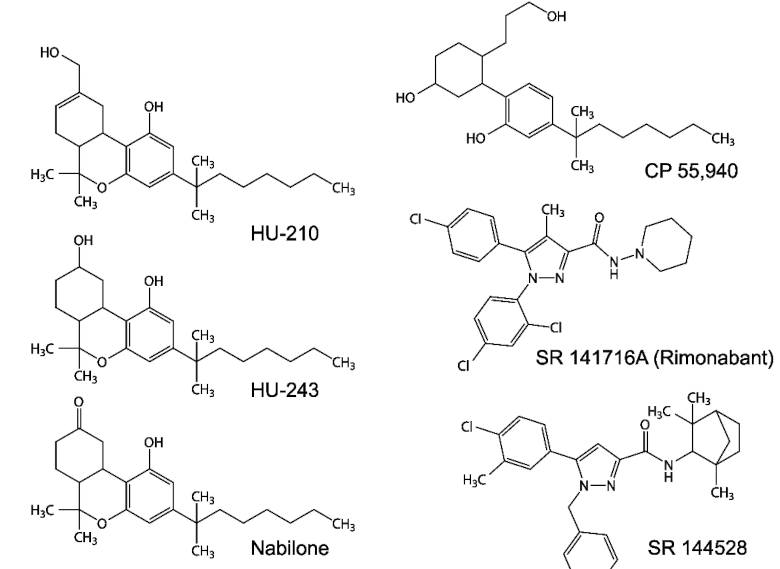

Synthetic cannabinoids are a broad class of chemical substances artificially created to mimic the psychoactive effects of natural cannabis. Although “synthetic cannabinoid” and “cannabis” sound similar, the two have little substantive relation beyond their mechanism of action. Like plant-derived tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), synthetic cannabinoids share the crucial feature that their active ingredients can bind to brain receptors for anandamide (Note 2). By slowing the signals sent and received between the brain and the central nervous system, they produce the sedative effects associated with so-called downer drugs (Note 3).

Synthetic cannabinoids were initially developed by pharmaceutical companies as potential new pain treatments, but it proved difficult to separate therapeutic benefits from psychoactive and toxic effects, making them uncontrollable. They quickly drew the attention of organized crime groups and drug users, moving from controlled research environments to the black market as so-called “legal highs.”

Chemical formulas of major synthetic cannabinoids (Image: chromatos / Shutterstock.com)

Synthetic cannabinoids are generally liquid substances and are sprayed onto plant material to resemble the appearance and consumption methods of natural cannabis. The plant base is often dried herbs such as damiana (Turnera diffusa) or marshmallow (Althaea officinalis), but these plants themselves are unrelated to the effects and function only as a medium for smoking or vaporizing.

The manufacturing process for synthetic cannabinoids generally involves three steps: The first is chemical synthesis of the drug, typically performed in a laboratory using chemical precursors. These include easily accessible household chemicals that can also be found in pesticides, herbicides, and adhesives. Next, the synthesized substance is applied to plant material. The compound is dissolved in a solvent such as commercially available acetone or ethanol and sprayed evenly onto dried plant matter. Finally, after the alcohol evaporates, the processed plant material is portioned into small amounts of about one to five grams.

When produced outside proper scientific laboratory settings, the process often lacks consistency and appropriate manufacturing conditions, leading to uneven potency and side effects, which is very dangerous. Because concentrations of synthetic cannabinoids are highly irregular, users may unknowingly ingest large amounts, leading to overdoses and other harmful side effects. This is why synthetic cannabinoids are considered dangerous even compared to natural cannabis or highly addictive drugs like cocaine or heroin. Although they act on the same brain receptors, their effects are typically stronger and longer-lasting. Overdoses magnify not only mental health issues such as hallucinations and paranoia, but also physiological problems including cardiovascular disorders like arrhythmia, kidney damage and renal failure, and respiratory attacks.

Because these substances are relatively easy to manufacture, the market is flooded with many homemade versions, each producing different outcomes. Such variability makes treating intoxication difficult: first responders cannot reliably predict specific toxic effects and administer the correct medication. Furthermore, standard drug tests (such as ELISA tests, Note 4) often fail to detect synthetic cannabinoids, which further delays diagnosis and treatment.

Chemical department of the police forensic laboratory in Warsaw, Poland (Photo: Fotokon / Shutterstock.com)

Distribution routes in Europe and V4 countries

The 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union brought sweeping changes to Eastern Bloc countries that had been under Soviet influence. Organized crime groups exploited vulnerabilities created by market expansion and relaxed travel restrictions. As a result, the 1990s saw an influx of traditional drugs such as LSD, amphetamines, and cocaine. However, over the past two decades, low-cost substances like cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids have spread. By the early 2000s, economic problems in Eastern and Central European countries had more clearly created demand for cheap and accessible drugs.

Synthetic cannabinoids can be purchased for a fraction of the price of expensive illicit drugs like heroin and cocaine seen in Western countries. When they first appeared in Eastern and Central Europe in the mid-2000s, they became an affordable alternative despite significant health risks. Today, synthetic cannabinoids are the largest group of psychoactive substances monitored by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA).

Geography also matters for the distribution of these drugs. For heroin smuggling, the Balkan route has been most commonly used. Traditionally starting in Afghanistan, and more recently in Myanmar, it passes through Iran and Turkey, reaches Central Europe via the Balkans, and much of it then flows to Western Europe. Cocaine and marijuana, originating in South American countries such as Colombia and Bolivia, arrive at ports in Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Belgium, and from there are distributed via road and rail networks, with much consumed in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, and a relatively small share reaching Central Europe. In contrast, for synthetic cannabinoids, the most important route is the so-called Northern Route. Synthetic cannabinoids are produced in China or—particularly since 2022—in Kazakhstan, then reach Central Europe via Russia and Belarus, or via Caucasus countries such as Georgia and Azerbaijan.

At the peak of their spread in the early 2010s, as many as 30 new synthetic variants were identified each year. These variants were found to have different chemical structures but were often only slightly modified to circumvent drug laws. In this way, they were introduced as “legal highs.” The V4 countries banned these substances between 2009 and 2012, but they could still be purchased through online shops based in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The turning point came in 2016, when an EU-wide ban was introduced. The figure below shows the number of synthetic cannabinoid variants formally notified to the EU Early Warning System (2008–2020). The peak in trafficking and the effect of the 2016 ban are evident.

Despite these legal measures, manufacturers continue to alter molecular structures to evade existing regulations. As of 2022, a total of 237 synthetic substances had been detected in Europe. As China imposed a comprehensive ban on the manufacture of synthetic drugs, illicit producers were forced to develop fundamentally new approaches. Production has shifted to the Northern Route, with Kazakhstan emerging as a major supplier for Eastern and Central European markets. It is also noteworthy that small-scale production continues within the V4 region, particularly in Hungary and Poland.

Trends in the V4

This section briefly examines the domestic situation in the V4 countries.

First, Hungary. A report on issues of national significance in 2021 indicates that an estimated 20,000–30,000 people regularly use synthetic cannabinoids, with use concentrated among impoverished communities, people experiencing homelessness, and those with criminal convictions. In Europe, the price of cocaine and similar drugs is thought to be roughly USD 30–120 per gram depending on purity, whereas a single cigarette containing synthetic drugs can be bought for as little as USD 0.25–0.40. Hungarian toxicologist Gábor Zacher has called synthetic cannabinoids a “drug of the poor.”

Slovakia shows trends similar to Hungary in both demographics and distribution. However, an increase in synthetic cannabinoid use has been reported, with teenagers and prison inmates identified as the primary users. Inmates evade detection by smuggling and consuming paper soaked in liquid synthetic cannabinoids.

Poland faces the most dire situation in the region. The country has seen a surge in hospitalizations related to synthetic cannabinoids, with examples of more than 150 people poisoned within a few days, including fatal cases. Poland introduced a ban on synthetic drugs in 2015, but this appears to have merely pushed the trade underground, with new variants continuing to emerge. Despite organized crackdowns, kiosks and corner shops in high-demand areas still sell synthetic drugs. Encrypted messaging apps such as Telegram and Signal play a key role in distribution, enabling suppliers to maintain a relatively stable customer base while evading authorities.

By contrast, the Czech Republic appears to have relatively fewer users of synthetic drugs than other countries, likely due in large part to the country’s lenient policy on natural cannabis, which allows possession of small amounts by law. However, because synthetic drugs are far cheaper than natural cannabis, demand remains high primarily among low-income groups.

Legal regulation and the challenges of rehabilitation

Europe has attempted to regulate synthetic cannabinoids through bans, but the rapid emergence of new cannabinoids, combined with low manufacturing costs and high demand, has made synthetic cannabinoids one of the most persistent drug problems in Europe, particularly in the V4 countries. One factor complicating law enforcement is that criminal groups in this region are largely organized in a decentralized manner. To mitigate the risk of sudden raids and arrests, these groups hire individuals with the promise of a cut and operate under the umbrella of larger organizations. In contrast to criminal organizations in East Asia, Italy, or the United States—often structured along family lines—criminal organizations in Eastern and Central Europe tend to be fundamentally profit-oriented, and small, lower-level segments are often sacrificed to protect the whole.

According to an interview with Central European law enforcement conducted on January 25, 2025, while synthetic cannabinoids are illegal across the region under existing laws, individual users and small-scale home producers face relatively light legal liability. This makes it difficult for law enforcement to exert leverage and roll up larger criminal organizations from the bottom when they attempt to prosecute higher-level groups.

The same law enforcement source added that, in most cases, criminal organizations maintain connections with law enforcement agencies and prisons through corrupt officials or former members currently serving sentences. This not only helps them learn and exploit real-world trends and laws concerning illegal activity, but also provides ongoing recruitment opportunities and new drug markets. As a result, a continuous “cat-and-mouse game” is being played between manufacturers and law enforcement.

Polish police (Photo: Cezary p / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

However, law enforcement measures are not necessarily effective for users of such drugs. One study found that treatment programs were 1.8 times more effective than enforcement measures at reducing drug use. Incarceration often hampers individual recovery and does not address the problem’s underlying social causes. It may therefore even contribute to higher relapse rates. In Central Europe, while addiction treatment centers and social reintegration programs exist, their effectiveness is often questioned. A 2018 survey found that about 25% of people experiencing homelessness in Hungary reported a lifetime prevalence of illicit drug abuse. Such distressed users may view drugs as a coping mechanism to escape the realities of their situation.

Furthermore, since their emergence, synthetic drugs have often been marketed as safe, legal alternatives to traditional illicit drugs. This misleads users about potential risks, discourages them from seeking treatment, and, even during treatment, can lead them to continue using synthetic substances, limiting the effectiveness of rehabilitation. Ultimately, because raw materials and production costs are low and the basic inputs are easy to obtain, synthetic substances are particularly attractive to low-income people marginalized from society, further complicating the social challenge.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while law enforcement agencies in the V4 region are making progress in the fight against synthetic cannabinoids and related criminal activity, major challenges remain. Since their emergence in the mid-2000s, synthetic drugs have become a significant issue in the V4 region over the past decade. The constantly evolving nature of these substances, low-profile production and distribution, economic incentives, and the cross-border scale of the problem continue to pose major obstacles. Synthetic drugs disproportionately affect the region’s low-income populations, exposing them to serious health risks and worsening already unstable social conditions.

How can local governments adapt laws and healthcare systems to address the relentless spread of synthetic drugs while simultaneously tackling the underlying socioeconomic problems? An effective response requires a multifaceted approach, including stronger regulations on manufacturers and distributors, bolstered social support programs for users, and enhanced international cooperation.

Note 1: Other names for synthetic cannabinoids: Spice, K2, Red X Dawn, Paradise, Demon, Black Magic, Spike, Mr. Nice Guy, Ninja, Zohai, Dream, Genie, Sense, Smoke, Skunk, Serenity, Yucatan, Fire, Scooby Snax, Crazy Clown (U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration).

Note 2: The name anandamide derives from ananda, Sanskrit for “joy, bliss, delight,” and amide.

Note 3: Many major drugs can be categorized as “uppers” (stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine) and “downers” (sedatives such as heroin and marijuana).

Note 4: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a common testing technique that detects and quantifies specific antibodies, antigens, proteins, and hormones in bodily fluid samples, including blood, plasma, urine, saliva, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Writer: László Bence Gergely

Translation: Kyoka Wada

Graphics: Ayane Ishida, Virgil Hawkins

0 Comments