In March 2019, President Nursultan Nazarbayev, who had held power in Kazakhstan, a country in Central Asia, for nearly 30 years, suddenly resigned. His resignation, after maintaining overwhelming control within Kazakhstan for many years, surprised people at home and abroad. Meanwhile, two months after his resignation—on May 9, 2019, one month before the new presidential election—large-scale internet censorship and access blocking were carried out in conjunction with opposition protests, and journalists covering the demonstrations were detained. Furthermore, on June 9, when it became almost certain that Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Nazarbayev’s successor, would become the next president as a result of the election, about 500 protesters and dozens of journalists covering events in the capital and elsewhere were detained, and some messaging apps became inaccessible. Although Kazakhstan is formally changing its head of state, there has been no sign of change in the harsh controls on expression.

Nazarbayev, who served as Kazakhstan’s president from 1999 to 2019 (Photo: President of Russia [CC BY 4.0])

To this day, controls on expression like those seen in Kazakhstan have been implemented across the countries of Central Asia. In countries with strict censorship, information that is disadvantageous to the regime or political system does not reach citizens or the outside world; voicing dissent is difficult, and even when it is expressed, it is erased. It is clear that censorship is obstructing liberalization and democratization in Central Asia. In this article, we examine the state of censorship in each Central Asian country.

目次

History of Central Asia

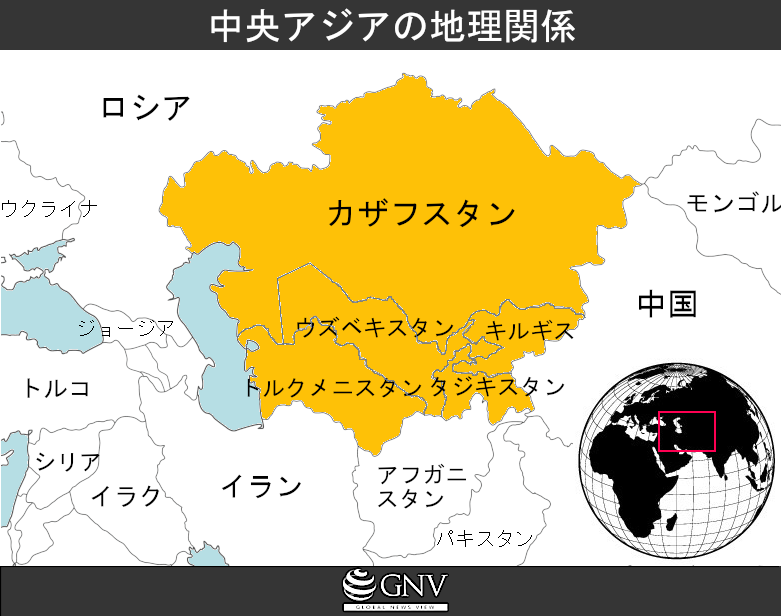

The five countries of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan; hereafter “the five Central Asian countries”) constituted the Soviet Union as Soviet Socialist Republics for roughly 70 years until independence. In the Soviet Union, since the 1917 Decree on the Press, freedom of expression was strictly limited through censorship and other means, and the voices of dissidents were hunted down. The Main Directorate of Literature and Publishing (Glavlit), established in 1921, censored every form of media—radio, television, books, newspapers—for decades thereafter to protect “state secrets.” During the Cold War, it is said to have had the world’s most wide-ranging and powerful radio jamming system, and speech control under the Soviet Union was firmly established.

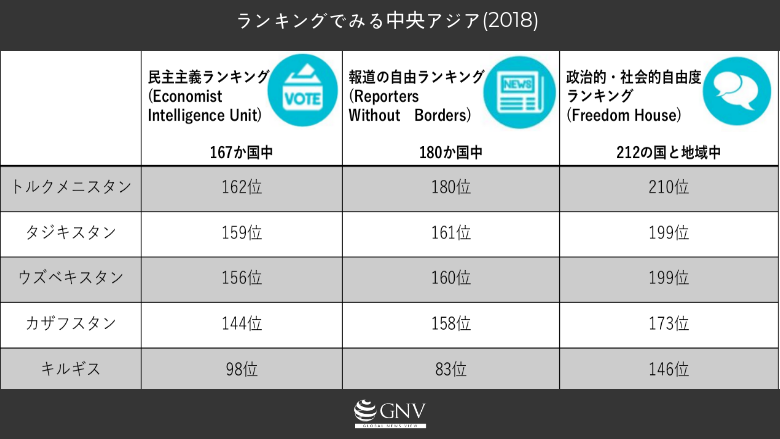

In 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the five Central Asian countries became independent one after another, but they did not abandon the authoritarian political structures—built during the Soviet era—that restricted freedom of expression. This is because the five Central Asian countries were not at the forefront of the liberation movements in the late Soviet period, and in most of them, the same individuals who had led the republican structures of the Soviet Communist Party continued to steer national politics after the Soviet collapse. Seizing the moment of the Soviet Union’s fall, they sought to establish new nationalist authoritarian regimes and consolidate powerful authority. Some researchers also link regional political culture—such as patriarchy, public obedience, and respect for elders and authority—to the entrenchment of authoritarianism. Regarding press freedom, the quarter century since independence can, in some respects, be seen as having actually worsened compared with the late Soviet period. In these countries, dissenting opinions are suppressed in the name of preventing incitement and maintaining public order, or freedom of expression is stripped away under the pretext of concerns about extremism. This is evident in various indicators published by different organizations, and the results are dismal.

Below, we introduce the situation in each Central Asian country in ascending order of democracy (from the lowest scores), based on the 2018 Democracy Index from the Economist Intelligence Unit.

Turkmenistan: The world’s most press-restricted country

Turkmenistan ranked last in the 2018 World Press Freedom Index (Reporters Without Borders), finally falling below Eritrea and North Korea. The country’s powerful, personality-cult-style dictatorship was built under the regime of Saparmurat Niyazov. Niyazov served as president from 1990 until his death in 2006, thoroughly eliminating opposition forces and establishing a dictatorship. The current president, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, who took office in 2006, has also strengthened authoritarian rule. There are no formal opposition parties in Turkmenistan. In the early 1990s, opposition parties were expelled, and the only legal party was the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan led by Niyazov. In 2003, four exiled opposition parties formed a democratic coalition based in Vienna, but they have had no ability to operate domestically and have minimal influence. In the parliamentary elections of March 2018, all candidates supported President Berdimuhamedow, making democratic parliamentary governance a distant prospect.

Such a dictatorship is sustained by the state’s complete control of the media. Until 2013, of the country’s 39 newspapers, five radio stations, seven TV stations, and one news agency, all but one were the president’s property. In 2013, a law on press freedom was enacted that ostensibly prohibited monopolies over media outlets, but today almost all newspapers still receive state funding, and television and radio remain state-run. The role of these media is to lavishly celebrate events such as the opening of new public facilities or the president’s visits to various regions, working to create a favorable image of the president.

UN agencies and international human rights organizations have repeatedly condemned the arrest and torture of journalists in Turkmenistan, but the government shows no sign of responding. Journalists continue to be arrested; some have been forced to confess through beatings, and others have died following detention and torture. In addition, it is believed that over a hundred people have been subjected to enforced disappearance, but such cases seldom come to light, and the full picture remains unknown. Will the day ever come when Turkmenistan can shed the ignominious label of being one of the world’s most authoritarian states?

A golden statue of former President Niyazov in the capital, Ashgabat (Photo: Chris Price / Flickr [ CC BY-ND 2.0] )

Tajikistan: A crisis for journalists

Tajikistan, like other Central Asian countries, became independent in 1991, but in 1992 anti-government forces took up arms, leading to a conflict that lasted about five years. Amid that conflict, in 1994, the current president, Emomali Rahmon, took office. He also holds power under an authoritarian system, and it is difficult for opposition parties to operate officially. Of the eight major political parties, six are pro-government parties, and in the 2015 elections for the Assembly of Representatives (the lower house), the opposition won only 2 of 63 seats.

President Rahmon does not tolerate criticism of himself or his government. In December 2017, journalist Khayrullo Mirsaidov, who wrote an open letter to President Rahmon exposing government corruption, was arrested. He was sued by the authorities for defamation and charged with embezzlement of state funds and making false statements to the police, receiving a prison sentence and an order to pay compensation. In Tajikistan, not only are journalists expelled by the authorities, but many also leave the country on their own due to threats, unjust imprisonment, and the contraction of media businesses caused by censorship, which reduces job opportunities. Moreover, even the families of those who peacefully criticize the government from abroad face threats to their safety. Under the pretext of counterterrorism and combating religious extremism, the authorities have blocked access to independent news outlets such as the major site Asia-Plus and to social media platforms such as YouTube and Facebook. In a country where the foundations of journalism have been thoroughly dismantled, seeking freedom is a daunting challenge.

Outside BBC headquarters in London, media workers call for the release of a BBC journalist arrested in Tajikistan (Photo: English PEN/ Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Uzbekistan: Glimmers of freedom

Uzbekistan likewise has a history of authoritarian rule, but in recent years it has shown slight signs of liberalization following the inauguration of a new president. Since 1990, Islam Karimov built a powerful dictatorship as president. Under his regime, repression of opposition forces was extremely severe; opposition parties were outlawed and driven into exile, and opposition members and their families were arrested on various pretexts. Even into the 2000s, attempts to form opposition parties were repeatedly thwarted and party registration was refused. In the elections of 2014 and 2015, multiple parties stood, but they were essentially uniformly pro-government, and the elections were not democratic.

However, the Karimov regime came to an end in 2016 with the president’s death. Shavkat Mirziyoyev then took office as the new president. From the perspective of freedom of expression, several measures under President Mirziyoyev can be positively evaluated. In the years since he took office, dozens of political prisoners, including journalists, have been released. In May 2019, access blocks on many major independent news sites were lifted. Many of these sites had been blocked since the Andijan massacre in 2005 (Note 1), and this decision is a major step toward liberalization of expression. On the other hand, it is also true that some sites remain blocked.

Moreover, many political prisoners have yet to be released, and incidents still occur—for example, in August and September 2018, bloggers who had criticized the government’s handling of religious issues were arrested on charges of resisting the police authority. Some journalists now report on issues such as corruption, but in such an opaque and unstable environment it is difficult to judge the limits of what reporting is permissible, which can foster self-censorship. Nevertheless, Uzbekistan is clearly demonstrating a forward-looking stance on freedom of expression and the press, and attention is turning to how far liberalization can proceed, including through the enactment and revision of laws.

A filmmaker working in Uzbekistan (Photo: Chris Schuepp/ Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Kazakhstan: End of a long-running regime and a presidential election disadvantaging the opposition

As noted at the outset, in Kazakhstan, Nazarbayev, who had held power since 1990, suddenly resigned in March 2019, and Kassym-Jomart Tokayev was elected the new president in the June 9 presidential election. Although Nazarbayev, who governed in an authoritarian manner for many years, resigned, he secured legal immunity from prosecution for life and continues to wield influence as the head of Nur Otan, the only party in Kazakhstan that effectively functions as a political party. In addition, because the period from resignation to the presidential election was shortened to just two months, it has been extremely difficult for the opposition to prepare for the election. This is because the opposition has been consistently suppressed to this day, making it difficult to raise funds and prepare for the election on short notice. Major opposition-run media outlets and websites have been shut down for years, making it difficult to get their message to the public.

Thorough controls on expression are not limited to opposition forces. Multiple independent websites have been forced to close due to political pressure, lawsuits and fines against members of the press have surged, and numerous journalists have been imprisoned. In 2006, well-known journalists Seitkazy Matayev and Asset Matayev, who had worked to protect the rights of journalists in Kazakhstan, were sentenced to prison and fines, and their buildings and other assets were seized. The trial in this case was conducted unfairly and drew attention from international human rights organizations, but there was little domestic response. This fact in itself shows how little freedom of expression is protected.

As a recent example, in March 2019, Svetlana Glushkova, a correspondent for RFE/RL (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty), a nonprofit that reports news in countries where press freedom is suppressed, was arrested while covering an anti-government protest. Other reporters who tried to film her arrest had their reporting obstructed. Even with a change of president, Kazakhstan’s direction will not change so easily.

Newly inaugurated President Tokayev (Photo: President of Russia[CC BY 4.0])

Kyrgyzstan: Central Asia’s hope

Kyrgyzstan is the most democratic of the five Central Asian countries. What sets it apart from other Central Asian states is that there have been two regime changes led by opposition forces, in 2005 and 2010, and on each occasion the president resigned. After the second upheaval, a new constitution was adopted by national referendum, introducing a parliamentary cabinet system and making Kyrgyzstan the first parliamentary democracy (Note 2) in Central Asia. Under this system of governance, parties, including opposition parties, have been developing; in the 2015 parliamentary elections, 29 parties participated and six parties won seats. Of the six, four were pro-government and two were opposition parties, and the two opposition parties together won about 33% of the seats.

As the state has advanced democratization, controls on expression have eased. Under President Sooronbay Jeenbekov, who took office in 2017, many lawsuits against media outlets, travel bans, and claims for damages were withdrawn. On the other hand, it is also true that some journalists remain imprisoned. Independent journalist Azimjon Askarov has been subjected to torture and abuse since he was imprisoned in 2010 following an unfair trial, and he has suffered since. Despite international protests, the authorities show no sign of altering his life sentence. With further improvements, we hope Kyrgyzstan will become a pioneer of liberalism in Central Asia.

Scenes from the 2010 unrest in Kyrgyzstan (Photo: Brokev03/ Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 3.0])

As we have seen, in the countries of Central Asia, authoritarian structures rooted since the Soviet era have tormented citizens in the form of censorship and hindered national development. Governments often refuse to listen to criticism of themselves, using concerns about extremism or incitement as a shield. Meanwhile, countries like Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have begun to show moves toward liberalization following the inauguration of new presidents. Although it is difficult at present to say that freedom of expression is sufficiently guaranteed in these countries, they are undoubtedly a ray of hope for a Central Asia long covered by the darkness of censorship. However, in Kazakhstan, cited at the outset, the presidency has passed to Tokayev, who declared that he would “continue to be guided by Mr. Nazarbayev.” The political outlook is grim, and the path toward democratization and liberalism still seems long.

Note 1: In the early morning of May 13, 2005, in the eastern city of Andijan, Uzbekistan, an armed group attacked multiple government buildings and stormed a prison to free 23 men accused of religious extremism. At the same time, a large-scale protest by unarmed citizens against the regime took place in the city. That afternoon, the Uzbek military blocked the square where the demonstration was taking place, causing protesters to flee, but hundreds of people were killed by government forces lying in wait.

Note 2: Parliamentary democracy is a political system in which a parliament, as a representative body of the people or residents, makes decisions in the form of legislation; a parliamentary cabinet system is a system in which the cabinet is responsible to the parliament and its existence depends on the parliament’s confidence. In Kyrgyzstan, a parliament existed prior to 2010, but since the new 2010 constitution—characterized by reduced presidential powers and expanded parliamentary powers—the country has adopted a parliamentary cabinet system and parliamentary democracy. The constitution was also amended in 2017, further strengthening the powers of the prime minister and the parliament.

Writer: Yumi Ariyoshi

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

We’re on social media too!

Follow us here ↓

中央アジア各国それぞれの説明が丁寧で分かりやすかったです!

中央アジア全体でキルギスやウズベキスタンのように自由化が進んでいくといいですね。

日本では言論統制をしている国として北朝鮮が取り上げられることがほとんどですが

それよりも厳しい言論統制がされている国の実態が報道されないのが現状だとわかりました

目次ができたんですね。

便利でいいと思います

元々GNVでトルクメニスタンの独裁については知っていたのですが、改めて中央アジア各国で情報統制がされている現実を知ることができました。

近年の日本でも情報統制が進んでいる気がして懸念があるのですが、政府が独裁に走らないように番犬としての役割を持つジャーナリズムを保護するような仕組みが重要だと思いました。

あと、目次機能すごくいいですね!

あまり海外のメディアでも中央アジアは注目されないので、中央アジアの言論の自由について知ることができて、勉強になりました。

言論の自由がないとして思い浮かぶのは北朝鮮ですが、中央アジア5カ国がかなり言論統制されていて驚きました。

ジャーナリストが拘束されることでさらにそうした国の状況が報道されることがなく、深刻な状況がと思います。

言論の自由が認められるようになるのは難しいと思いました。

(異論は認めますし、自分でもたくさんの反論があるのですが)内政不干渉の考え方・そこで住む人間が幸せなら良いという考え方は確かに存在し、そういった考えを背景にしたとき、今回取り上げられた5カ国の平和状態が気になりました。紛争などが継続して発生していたりするのでしょうか?