“Antibiotics.” Most readers have probably heard the name at least once, or even taken them. Antibiotics are substances that inhibit the growth of microorganisms such as bacteria and are effective against all kinds of bacterial infections, including pneumonia, tuberculosis, bacterial food poisoning, cystitis, and impetigo (contagious impetigo). Today, antibiotics are being taken about 16 times per 1,000 people per day around the world, and have become indispensable medicines for maintaining people’s health.

However, the era in which antibiotics “don’t work” is right around the corner. Drug-resistant “superbugs” are emerging, and cases in which the prevention and treatment of infections that used to be possible are becoming difficult are increasing rapidly around the world. The number of people who die from infections caused by superbugs amounts to about 700,000 per year worldwide. Why are antibiotics becoming ineffective in today’s advanced medical age? This article gets to the heart of the issue.

Antibiotics (Photo: PublicDomainPictures / Pixabay)

Case study: The antibiotic resistance problem seen through one boy

A case covered by the UK’s Independent illustrates the terror of the antibiotic resistance problem. Here, we introduce that case.

Raman, a 15-year-old boy living in Delhi, India, noticed blood mixed in his phlegm when he coughed while playing with friends. After returning home, he went to the hospital with his mother, where he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and prescribed four antibiotics for six months. Due to the symptoms of the illness and the side effects of the drugs, Raman suffered from dizziness, nausea, and weakness. However, even after half a year had passed, his symptoms did not improve at all, so he continued taking the medication for another three months. Still not recovering, he underwent detailed examinations at another hospital. It turned out he had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Of the drugs he had been taking for nine months, two were ineffective for Raman, and he remained infected with tuberculosis. Raman had to continue injections for another six months and take several different antibiotics. In addition to the nine months so far, another two years of treatment would be necessary.

With such prolonged drug therapy, patients’ physical strength declines, and they sometimes suffer from serious side effects such as hearing loss. Families may also struggle with poverty due to the high treatment costs. Even with this treatment, fewer than half of MDR-TB patients are cured. In addition, there is an even more dangerous case: “extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.” This is tuberculosis caused by bacteria resistant to a broader range of antibiotics than conventional MDR-TB, and if contracted, the chance of cure is only about one-third.

It was fortunate that Raman was diagnosed with MDR-TB and began treatment. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), among children under 15 worldwide, 1 million become infected with tuberculosis each year, of whom 230,000 die.

An Indian child with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (Photo: CDC Global / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The existence of such drug-resistant bacteria is by no means limited to tuberculosis. Bacteria resistant to all antibiotics have now been found.

Why are antibiotics becoming ineffective?

The biggest cause of the spread of antibiotic resistance and superbugs is the overuse of antibiotics and inappropriate prescribing and consumption worldwide. There are several aspects to this.

First, we humans are taking antibiotics too often. There are many cases in which antibiotics are prescribed or taken when they are not necessary—for example, for most colds and influenza, which are viral illnesses. Antibiotics are effective against bacteria but not against viruses. Nevertheless, many people firmly believe that colds and influenza can be cured by antibiotics and therefore seek them out. This leads to antibiotics being prescribed in unnecessary situations, causing overuse. There are also cases where people stop taking antibiotics on their own when symptoms improve, or use leftover antibiotics on another occasion—factors that contribute to the proliferation of superbugs.

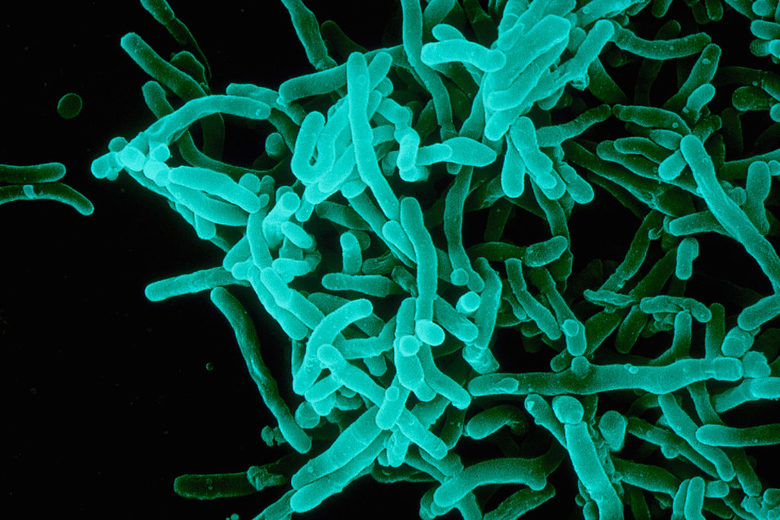

Diphtheria bacteria (Photo: Sanofi Pasteur / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

As a secondary line of defense to stop resistance, several antibiotics that should be prescribed only when resistant bacteria are detected have been designated as “antimicrobials to be used as restrictively as possible,” but according to a WHO survey, in 49 of the 65 countries surveyed, these drugs account for more than half of all antibiotics prescribed.

Especially in developing countries, due to insufficient budgets, appropriate drugs cannot be obtained, leading to inappropriate prescribing of readily available antibiotics. In many cases, governments and medical institutions lack adequate management systems, and record-keeping on prescriptions is insufficient. In this way, multiple causes interact in complex ways behind the antibiotic resistance problem, making countermeasures anything but straightforward.

Furthermore, excessive use in livestock is also a major cause. About half of the total volume of antibiotic use is in livestock. To prevent disease and promote growth and reproduction, large amounts of antibiotics are used in healthy animals. As a result, as with humans, drug-resistant bacteria—superbugs—have been detected in livestock and other animals, and the spread of “incurable” diseases in animals is a concern. Moreover, drug-resistant bacteria that arise in animals can infect humans, making the superbug problem in animals quite serious.

Piglets being raised in a piggery (Photo: Natural Resources Conservation Service / Wikimedia (Public Domain)

In this way, overuse of antibiotics by people and animals accelerates the emergence of bacteria that are resistant to them, creating “untreatable” conditions for diseases that should be treatable.

Antibiotic development is not advancing

What further worsens this situation is that many major pharmaceutical companies are withdrawing from developing new antibiotics.

The urgent task posed by the antibiotic resistance problem is to develop new drugs to counter bacteria that are resistant to conventional antibiotics, and that is the only means to save people who are suffering from resistant bacteria “now.” Even if antibiotics are used appropriately, bacteria are constantly evolving. The development of new antibiotics is essential for human health.

However, many pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to embark on developing new antibiotics, calling it “low-return.” It is said that developing anti-cancer drugs yields twice the profits of antibiotics. In fact, over the past 30 years, hardly any new antibiotics have been developed. According to reporting by The Guardian, experts say, “Governments need to provide incentives so that companies can advance new drug development and make the sale of antibiotics easier, just as companies produce conventional antibiotics.”

Can humanity stop antibiotic resistance?

If we take no action against the antibiotic resistance problem, it is estimated that by 2050, 10 million people per year will die due to superbugs (drug-resistant bacteria). This number exceeds deaths from cancer. Many deaths are expected especially in Asia and Africa, with numbers reaching 4.73 million in Asia and 4.15 million in Africa. In Europe and America as well, nearly 300,000 people are projected to die annually in each region due to drug-resistant bacteria. Moreover, the economic loss is said to exceed $100 trillion per year.

Currently, with the WHO at the center, countries and institutions around the world are being engaged to promptly implement various countermeasures. Here we introduce two of those measures. The first is the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS). This system enables the collection, analysis, and sharing of data on antimicrobial resistance at a global level, aiming to promote countermeasures in communities and countries. Next is the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP). Established in 2016 by the WHO and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), this nonprofit promotes the research and development of new antibiotics through cross-border public–private collaboration. By improving existing antibiotics and promoting the development of new ones, it aims to develop and provide four new treatments by 2023.

A practical lesson on antibiotic resistance in livestock in Southeast Asia (Photo: Richard Nyberg, USAID Asia / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

In November 2018, chemists at Stanford University in the United States developed a new treatment for infections caused by one drug-resistant bacterium, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Rather than developing a new antibiotic, they found that simply adding an additive to existing common antibiotics is effective against infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria. This may be a significant step toward overcoming the antibiotic resistance problem.

For the antibiotic resistance problem to move toward resolution, efforts by various actors are essential. Government agencies need to strengthen surveillance and management systems for the use of antibiotics and infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria (superbugs), and provide incentives to pharmaceutical companies for antibiotic development. Medical institutions and healthcare professionals should prescribe antibiotics only when medically necessary. Those involved in agriculture should refrain from administering antibiotics for the purpose of promoting growth in healthy livestock or preventing disease. Patients, too, are asked not to request antibiotics when physicians judge them unnecessary, not to stop taking antibiotics on their own, and not to use leftover antibiotics on another occasion or share them with others.

Will these measures be able to defeat bacteria and superbugs that continue to evolve at a staggering speed? The outcome depends on how seriously humanity can tackle this issue. The antibiotic resistance problem is no longer someone else’s concern. The threat of superbugs is already rapidly robbing us humans of our health.

Writer: Yuka Matsuo

これまでスーパーバグの発生は仕方のないことだと思っていましたが、我々の服用方法もその一端を担っていることに驚かされました。私自身、抗生物質の使いまわしや独断で摂取することがありますので、まずは個々人の理解が必要ですね。

短期的なスパンで物事を捉えがちな人の性が如実に現れている問題なのかな、と思います。だからといって仕方ないで終わらせられるはずはなく、解決に向けて必要な取り組みが明らかな以上、それぞれのアクターが主体的に行動あうるような国際的な取り決めを設定することが求められます。