On July 9, 2018, an elite prosecutor who had overseen about 4,000 arrests was dismissed under pressure from parliament. Her name is Laura Codruța Kövesi. Appointed in 2013 at the age of 33 as the youngest-ever head of Romania’s National Anticorruption Directorate, she exposed corruption among many prominent figures, including senior government officials and mayors, and could be called a beacon of hope for Romania, a country plagued by deep-rooted corruption nationwide. What does it mean that, after five years in office, she was removed from her role in the fight against political corruption in her homeland?

Laura Codruța Kövesi, head of the National Anticorruption Directorate. During her approximately five-year term from 2013, she oversaw about 4,000 arrests (Photo: AGERPRES /Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 3.0] )

In Romania, corruption is rampant across a very wide range—politics, the military, healthcare, and private business—raising concerns among foreign investors. The situation is serious because corruption is also seen in public offices, including the police and the judiciary, which ought to be countering illegal acts.

Beyond corruption itself, attention should also be paid to the fact that within the legislature—parliament—moves are underway that encourage it. The ruling Social Democratic Party (Partidul Social Democrat, hereafter PSD) has been pushing legal amendments intended to pardon corruption by politicians from its own ranks. Resisting this situation are anti-government demonstrations by the public. Parliament, which is advancing measures that promote corruption, and the people who oppose them have traded blows repeatedly, and in 2018 there were very significant developments.

This article explains Romania’s recent corruption problem. What path has the largest country in the Balkans taken over the past few decades, and where does it stand now? Using the single keyword “corruption” as an axis, we will survey contemporary Romanian politics.

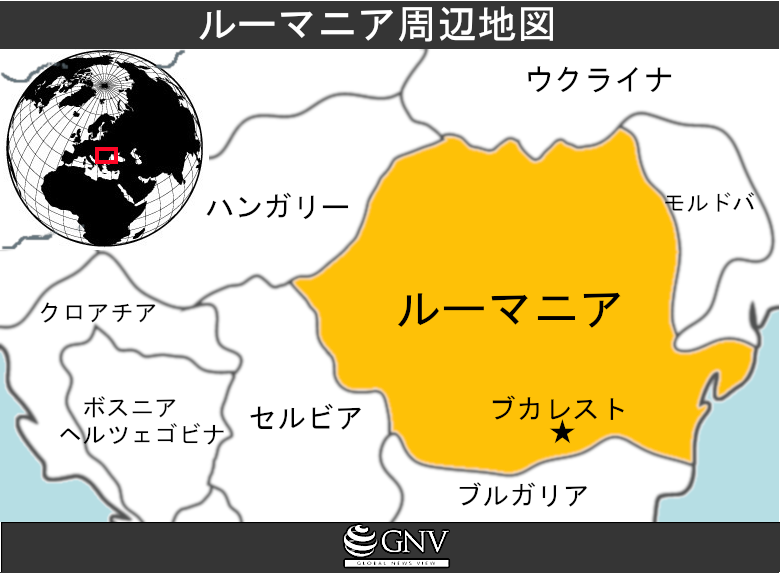

Basic information on contemporary Romania

Before delving into the issue, let us briefly organize some basic information on contemporary Romania. Romania is a country of about 19.76 million people (2016) with an area of roughly 238,000 square kilometers, located in Eastern Europe. After World War II, it adopted communism as a Soviet satellite, but the Communist regime led by President Nicolae Ceaușescu collapsed in the 1989 revolution, ushering in democratization. Although its economy lagged compared to other Eastern European countries after independence, reforms toward macroeconomic stabilization and a market economy advanced in the late 1990s with financial assistance from Western Europe, and in 2007 it joined the EU together with Bulgaria during the bloc’s fifth enlargement. Since then, despite alternating periods of growth and stagnation, the economy has accelerated markedly since 2015, and as of 2017 it had the highest growth rate in the Central and Southeastern European region.

Romania’s political system is as follows. It is a republic with a president, elected directly by the people, as head of state, and it adopts a semi-presidential system in which a prime minister chosen by parliament leads the government. Parliament is bicameral with four-year terms, and the president serves a five-year term. Under the constitution, parliament and the president possess almost equal powers, and when they clash, national politics tends to stall. In fact, as of January 2019, President Klaus Iohannis, who comes from the opposition, faces a coalition government centered on the PSD, producing a state of divided government between the president and parliament/cabinet has arisen.

From politics to business: the state of corruption in Romania

Corruption is a serious problem in Romania. In Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, which focuses on corruption in particular, the country ranked 59th out of 180 countries as of 2017 (a lower rank indicates greater corruption), making it the third most “perceived as corrupt” country in Europe.

One sector where corruption occurs frequently is politics. At the national level, for example, in 2009 businessman Ioan Niculae was imprisoned for two years for providing illegal campaign funds to the PSD. As in the central government, corruption is also rife in local government. In 2014, the mayor of Cluj-Napoca was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for receiving a bribe of 94,000 euros in exchange for contracts related to auto insurance for city cars and garbage trucks.

Palace of the Parliament (Romanian parliamentary building) (Photo: Cristian Iohan Ştefănescu /flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

The scope of corruption is not limited to politics. In various fields such as the judiciary, police organizations, public services, and the media, corruption to varying degrees is observed. For example, at the water utility Apa Nova, several employees were continuously bribed between 2008 and 2015 in exchange for raising tariffs on water and sewage, which increased the company’s net profit by 6 million. Moreover, although the judiciary is nominally independent, in practice it operates under strong pressure from the legislature (for example, the legislature can abruptly change standards regarding the regulation of corruption), and there are repeated problems in which bribes within the judicial branch influence court rulings.

The National Anticorruption Directorate and people power confronting pervasive corruption

As noted above, corruption is widespread across many sectors in Romania, but at the same time, active countermeasures have also been taken. Playing a central role in anti-corruption efforts from within the government apparatus is the National Anticorruption Directorate (Direcţia Naţională Anticorupţie, hereafter DNA). As its name suggests, the DNA’s mission is to clamp down on corruption in all fields, and especially since the appointment (2013) of Director Laura Kövesi introduced at the outset, it has successfully cracked down on numerous cases. In 2014, 1,138 people were indicted, and in 2015 there were also 970 convictions, among other results, with many corrupt acts prosecuted by the agency.

Nor have citizens outside the public administration stood by and watched corruption in silence. Grassroots popular movements have shown resistance to corruption from a non-institutional angle. In 2012, triggered by reforms to the healthcare and welfare system that undermined living standards and motivated in part by protests against high unemployment, economic conditions, and government corruption, an anti-government movement took place. Since then, civic movements have achieved not insignificant results in the anti-corruption push, with the large-scale protests of 2017 a good example. In January 2017, when parliament proposed a bill to pardon those convicted of certain crimes with sentences of up to five years, and a bill to decriminalize abuse of power that caused budgetary damage of less than USD 47,522, protests were held across the country. At their peak on February 5, as many as 500,000 citizens took part, and even after the government withdrew the bills, the movement continued as a protest against the ruling PSD, forcing Prime Minister Sorin Grindeanu to step down in June.

Romanian citizens participating in a protest in the capital, Bucharest (Photo: Mihai Petre /Wikimedia commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Is the government gaining the upper hand over anti-corruption efforts? Events of 2018

As seen in the previous section, anti-corruption efforts advanced by government agencies and by civic movements have achieved certain results, but in 2018 that momentum began to run aground. Below, we review several important developments in Romanian politics in 2018 in chronological order.

First, in January 2018, the cabinet of Mihai Tudose submitted a new bill. The bill included provisions such as requiring corruption suspects to attend victims’ hearings in court, permitting house searches only after suspects had been notified, and excluding video recordings from investigations, which were described in the cabinet’s proposal and seemed intended to make corruption convictions more difficult. In response, crowds estimated at between 50,000 and 100,000 staged protests, and succeeded in having the bill rejected and in forcing Prime Minister Tudose to resign.

However, about half a year later in July, the situation took a darker turn. Under pressure from a parliament dominated by the PSD, the aforementioned DNA director Laura Kövesi was removed from her post. In response, on August 10, anti-government protests broke out across Romania. Romanians who had emigrated abroad (the Romanian diaspora) returned to join the protests, which became large-scale demonstrations, with 100,000 participants in the capital Bucharest alone and tens of thousands more in other cities. The government deployed police to suppress them by force; in total, 455 people were injured and 30 were arrested. Ultimately, the protests succumbed to the government’s violent crackdown and subsided without securing Kövesi’s reinstatement.

Violent clashes between police and demonstrators (Photo: Cristian Iohan Ştefănescu /flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The PSD’s efforts to impede the crackdown on corruption continued to advance thereafter, and in October, legal changes tightened the requirements to become anti-corruption prosecutors. In backlash against such moves, about 2,000 people held a demonstration in the capital in December, but it failed to achieve any notable results.

The EU has expressed concern over these trends in Romania’s parliament. In January 2019, at a press conference with Romanian President Iohannis, it sounded a warning to the Romanian government, saying that legal amendments to grant pardons to those accused of corruption would “damage the essence of the EU.” President Iohannis had already shown a stance of fighting corruption, including criticizing parliament’s course in sympathy with the protests of January 2017. How he will act in response to the direction taken by parliament bears watching in the future.

The road ahead for Romania and Europe

This article has surveyed the political history of the 2010s with a spotlight on the corruption problem within Romania and the responses of the DNA and the public that oppose it. In Romania, corruption is rampant across various sectors—politics, the judiciary, private enterprise—and parliament is pushing legal amendments that foster it. In response, the DNA as an enforcement agency and ordinary citizens have continued to resist, but as of 2018 their struggle has entered a difficult phase.

Such political corruption is not unique to Romania; neighboring Bulgaria (ranked 73rd worldwide in the 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index) and Belarus (68th in the same), among other Eastern European countries (the former communist bloc), face the same challenges. Taken together with the rise of populist forces in Western and Central Europe, one could say that democracy in Europe is facing a difficult phase.

Writer: Shunta Tomari

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

Follow us here ↓

汚職が蔓延しているだけではなく、それ助長するような法制度を押し進めているルーマニアに非常に危機感を感じました。

特に司法や警察などの汚職は、国民の人権侵害に繋がりかねないため、ルーマニア内部で汚職促進の動きが止められないのなら、EUのように外部から働きかけて立法制度や行政を根本的に改革させる必要があると思いました。

良心のある市民が戦っているというのは、すごく勇敢な事だと思います。

屈せずに立ち上がり続けて欲しいです。

政治腐敗は東欧にも広がっているんですね、、

腐敗を暴く役割のメディアが弱いんですかね?それも気になりました。

国家ぐるみで行われる深刻な汚職に対して、果敢に立ち向かう民衆の勇気に少し感動しました。このような記事がもっと取り上げられ、いわゆる国際社会での批判が強まることで同国が事態を改善させることを望みます。