The “stability” long maintained by the Central African nation of the Republic of Cameroon is now being profoundly shaken. Cameroon has historically been described as a country that has maintained political stability. Since its independence in 1960, it had experienced neither armed conflict nor coups until recent years. The fact that the same president has ruled the country for 37 years since 1982 could be seen as emblematic of that. Yet Cameroon now faces a grave crisis: a conflict has erupted that has left more than 600 dead. Why did such a conflict arise in Cameroon, a country once known for its stability? Let us unravel this alongside Cameroon’s history.

History of Cameroon: The colonial era and division

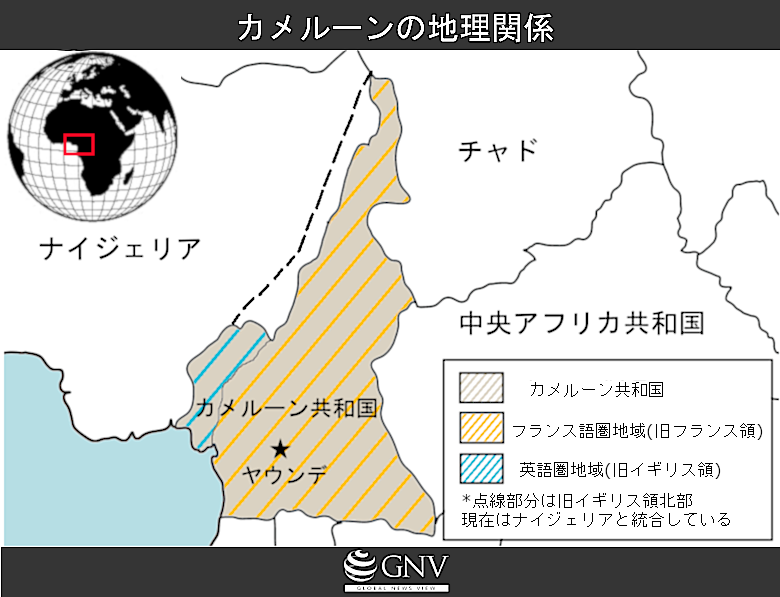

Behind the outbreak of conflict in Cameroon lies a complex historical background. In the 1870s, during the Scramble for Africa as European powers vied for and colonized African lands, Cameroon was colonized by Germany. However, after Germany’s defeat in World War I, which began in 1914, Cameroon was handed over—its northwest to Britain and its southeast to France. In terms of population ratio, it was about 2:8, meaning most of it became French territory. From there, British Cameroons was further divided into the Northern and Southern parts.

In 1960, known as the “Year of Africa” as African nations gained independence one after another, French Cameroon also achieved independence as the Republic of Cameroon. Then in 1961, separate plebiscites were held in Northern and Southern British Cameroons: the Northern part was integrated into neighboring Nigeria, which had also gained independence in 1960, while the Southern part decided to form a federation with the former French territory.

Relations between Anglophone and Francophone Cameroon

Although Cameroon settled into its current form after territorial division, de facto it remains split into Anglophone and Francophone regions, and the relationship between them has been closer to confrontation than to friendship. With 80% of the population in the Francophone regions, Francophone influence has gradually expanded, putting pressure on the Anglophone regions.

In 1972, the federal system was abolished and Cameroon became a unitary state, and three years later in 1975, the national flag was changed from having two stars to one. While that symbolized the unification of the Anglophone and Francophone Cameroons into one, in reality, since the abolition of federalism no one from the Anglophone regions has become the nation’s leader, reflecting the expanding monopolistic dominance of the Francophone side.

A tower built to commemorate Cameroon’s reunification (Photo: Z. NGNOGUE /Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Furthermore, the Cameroonian constitution stipulates respect for the culture of people in the Anglophone regions, and as official languages, French and English are both designated. Of the 10 regions, eight apply a legal system modeled on French law, and two apply a legal system modeled on English law, which is implemented. Despite policies aiming at coexistence and equality between the Francophone and Anglophone regions, in practice very few citizens are bilingual, and government documents and policies have never been printed in English; the two languages are not treated equally. In this way, the Anglophone regions are effectively subject to political exclusion.

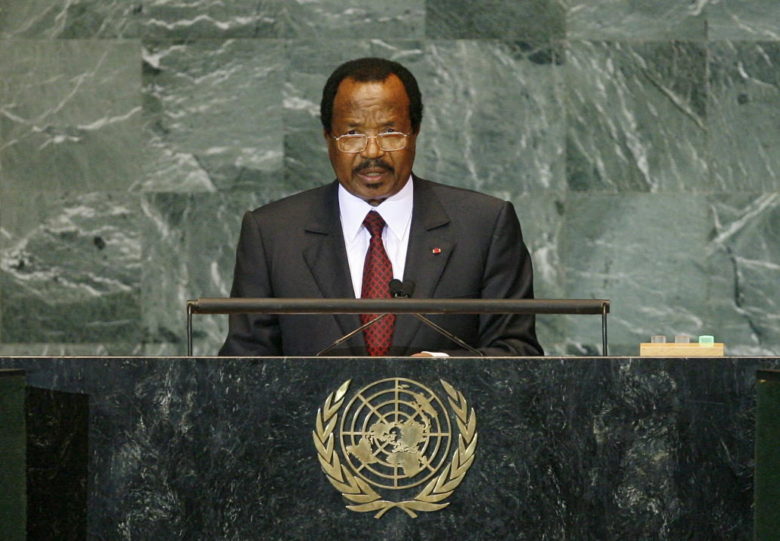

The Anglophone minority is treated in a discriminatory manner, and inequality between the two sides remains deeply entrenched. Exacerbating this situation, one could say, is President Paul Biya, from the Francophone regions, who has ruled Cameroon for 37 years since 1982.

President Paul Biya speaking at the UN General Assembly (Photo: United Nations Photo /Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

President Biya became well known for having worked as an official under President Ahmadou Ahidjo, who had governed Cameroon since 1966. Enjoying Ahidjo’s strong trust, he served as chief of staff and minister of state, and in 1975 became prime minister of Cameroon. In 1979, he was designated as the constitutional successor to the presidency, and after President Ahidjo’s resignation in 1982, he assumed office as the new president.

Biya’s style of governance is highly authoritarian. Many political decisions are made by presidential decree, and in some matters there is little parliamentary consultation. Although Cameroon has many parties, in practice it is a one-party state under the Cameroon National Union, with many other opposition parties marginalized. The discriminatory treatment of French and English is also orchestrated by the central government, including Biya; the president himself is creating the discriminatory situation. Though Cameroon had long been called a stable country, behind that stability lay political tightening by the president, which has led the country into instability.

Toward armed conflict

In 1985, Fon Gorji Dinka, an Anglophone lawyer and president of the Cameroon Bar Association, declared the Biya administration unconstitutional and demanded new independence for the Anglophone regions as the Republic of Ambazonia (※1). However, Dinka was imprisoned without trial by the government, and the claim for Ambazonian independence was summarily dismissed. With Anglophones making up only about one-fifth of the population, even if they resisted the government, it amounted to little and was crushed by state power.

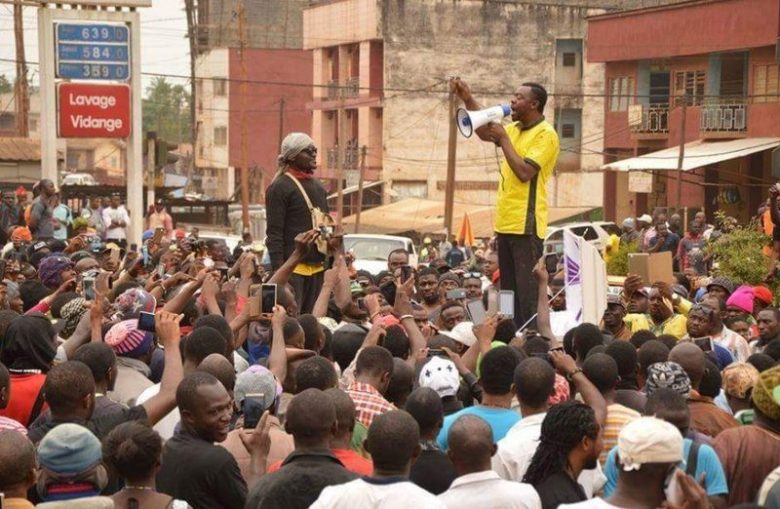

Demonstration in Cameroon (Photo: Activist/Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 4.0]

A turning point came with a small protest in 2016. In response to policies announced by the government—such as hiring Francophone teachers and lawyers in schools and courts in the Anglophone regions, and requiring French proficiency to become a civil servant—Anglophone lawyers held protests, with teachers who agreed joining in a strike. The protests themselves were peaceful and did not involve riots, but the government labeled Anglophone activists extremists, brought terrorism charges against them, cut internet access in the Anglophone regions, and suppressed critical media—excessive sanctions that included violence against organizers to quell the protests. This triggered riots and developed into domestic conflict between the government and the Anglophone regions.

The police and military carried out indiscriminate arrests, torture, and killings of people in the Anglophone regions in an effort to quell the unrest by force, but it did not subside easily. Later, President Biya restored internet access in the Anglophone regions, released protesters, established a National Commission for the Promotion of Bilingualism and Multiculturalism, and hired more Anglophone administrators, which led to a temporary lull in the unrest.

Since the 2016 protests, numerous protest actions have continued against the government. These were not limited to inside the country: in front of the UN headquarters in the United States, a demonstration was held calling on the UN to pressure the Cameroonian government and to release detained Anglophone activists. Others were also held in front of embassies in Washington, D.C., France, Germany, and the Netherlands. However, the government’s response has been slow to change.

People in the United States holding the flag of the Republic of Ambazonia and protesting (Photo: Lambisc /Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Discrimination against the Anglophone regions also continues: unemployment among people in the Anglophone regions is high, and the U.S. State Department’s human rights report documents human rights abuses against people in the Anglophone regions, stating that abuses against them are not punished.

In October 2017, intense protests erupted again, and multiple armed groups opposing the government were formed, which began fighting government forces. The government sought to quell the unrest based on an anti-terror law adopted to address Boko Haram in neighboring Nigeria, but it has not subsided to this day, and a peaceful resolution has not advanced. Over the course of 2017, more than 420 civilians, more than 175 soldiers and police officers, and hundreds of combatants were killed, and more than 300,000 people were forced to leave their homes, with displacement continuing.

Cameroonian military (Photo: US Army Africa /Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

External threats shaking Cameroon

Cameroon’s stability is being undermined not only by domestic issues but also by problems coming from outside. First is Boko Haram, an extremist armed group that has pledged allegiance to the Islamic State. Based in Nigeria, Boko Haram has in recent years infiltrated northern Cameroon and Niger, killing and abducting residents, burning hundreds of homes, and looting property such as livestock. The group frequently uses children in suicide bombings, and many students have been abducted. Cameroon has received many refugees from Nigeria, and has also accepted 300 U.S. troops to counter Boko Haram. Numerous reports have also documented human rights abuses by Cameroonian forces against civilians during counter–Boko Haram operations, leaving the security situation in northern Cameroon highly unstable.

Another factor is that Cameroon, as a neighboring country, has accepted many refugees from the Central African Republic (CAR) conflict. In CAR, clashes among multiple armed groups, driven by a range of factors such as history, power, and religion, have erupted. At the height of the conflict, 1.2 million people—one in four citizens—were forced to flee their homes within or outside the country. Cameroon is the largest host of CAR refugees; now, in addition to 241,000 internally displaced people, it hosts 88,000 Nigerian refugees fleeing Boko Haram and 249,000 CAR refugees, making Cameroon’s situation even more unstable.

Nigerian refugees who fled to Cameroon (Photo: USAID U.S. Agency for International Development /Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Efforts toward peace

In the face of such a tragic situation, what is being done to restore stability to Cameroon? While there is not complete indifference to this conflict, perhaps it is not being taken seriously enough; there has been little urgent action. First, Cameroonian Muslim and Christian leaders have attempted to mediate and called for peace, issuing a statement urging both the military and anti-government forces to lay down their arms and stop the violence. As there are many Muslims and Christians in Cameroon, their leaders’ words should have influence, but the government insists that only armed anti-government forces should disarm, and their mediation efforts have not progressed as hoped.

As for external responses, the chair of the African Union visited Cameroon in July 2018 and met with President Biya to discuss the reality of the situation. However, the visit ended with acceptance of President Biya’s expression of commitment to promoting peace, and even after the AU’s proposal to intervene in Cameroon’s issues was rejected, the chair did not press the matter further. The UN Security Council has discussed the conflict, but no statement or decision has been adopted.

The future of Cameroon

A presidential election was held in October 2018, and 85-year-old President Paul Biya was re-elected. His vote share was a high 71%, but allegations of vote-padding by the Biya camp have been raised, making it hard to call the election fair. At the very least, as long as the president—who bears part of the responsibility for the outbreak of this conflict—continues to wield overwhelming power, can peace return to Cameroon? Reconciliation between the Anglophone and Francophone regions is not progressing, and external efforts toward peace remain weak. How will this conflict unfold from here? One can only hope that Cameroon, where domestic and external issues are intertwined in complex ways, will once again be called a stable country.

※1 Republic of Ambazonia (Federal Republic of Southern Cameroons): The point where the West African and South African coastlines meet is called Ambas Bay, and because the Southern Cameroons asserting independence this time is located around Ambas Bay, it was named the Republic of Ambazonia.

Writer: Wakana Kishimoto

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

カメルーンという名前はよく知っていましたが、イギリス領とフランス領で分裂していたことさえ知りませんでした。

隣国の中央アフリカの紛争も酷いものですが、その難民を多く受け入れるのも本当に大変だと思います。

この紛争の要因として国外からの影響が挙げられており、決して他国が放置して良い問題ではないことがわかりまひた。

無数の言語があるアフリカでは、このような言語の壁による対立は、カメルーンに止まらず他の国でも起こっていそうだと思いました。

非常に難しい問題ですが、言語に関係なく活躍できる社会が実現には何が必要なのか、すごく考えさせられます。

理念や目標として大いなる理想を掲げたとしても、実態としては数の暴力によってマイノリティが圧迫されるという事態の象徴だと感じました。日本でも広く議論されているダイバーシティの問題と共通する部分があり、マジョリティ側がアファーマティブアクションのように手を差し伸べていくほか、表現の自由をしっかりと保障する必要があるのかなと、思います。

使用言語が異なることによって生じる問題は、(勿論容易ではないものの)テクノロジーの発展がその解決に寄与する部分が大きいと思うので、様々な面からのアプローチによって早期の和平が実現されることを願うばかりです。

「安定」の良し悪しはどう捉えるかによって全く変わるなと感じました。

様々な問題をはらんでいるけど表面上は「安定」をとるか、変革を起こすために「安定」を壊すのかの境目に立っていたカメルーンがついに行動を起こした、という風に感じました。

英語圏もフランス語圏も文化的にある程度独立した地域なので、国として独立するのが最善策ではないかと思いますが、争い事なくスムーズにそれが行われることはないんでしょうかね。

経済格差なんかもありそうですね、人口の流入にも関わりそうです。

1つの国で言語が異なることでこのような紛争が起こっており、さらに、政府がそのような政策をとっていることにも驚きました。大統領が変わらない限り状況が良い方に変化する可能性は低いと思うので、国連や他国の支援が必要だと思いました。

歴然な力関係が存在する二つの地域における連邦制は、人間の性とも言える差別意識(優越感を持つことによって自己を正当化させる意識)を醸成させるため、将来的に不用意な対立を生んでしまうことを学びました。差別意識のような人間の「自己保存」の本能に反してもうまく行きはしないので、自己保存を逆手に取る国家制度設計(または国際機関の支援)が必要だと考えます。英語圏地域とフランス語県地域が対等な関係性のもと共創していく国となることを願います。