The word “hagetaka” (“vulture”). Biologically speaking, there is actually no bird that bears this exact name, but it has become a common nickname applied to carrion-eaters such as condors or vultures. Because both swarm over carcasses and gorge on carrion, “vulture” is often used to describe villains who prey on the weak for their own self-interest. Among those infamous for carrying such a label are companies known as “vulture funds.” Thanks to novels and TV dramas, many may have heard the term, but when viewed through their relationship with nation-states, a new picture emerges. This article seeks to decipher the impact vulture funds have on states around the world.

Vulture (Photo: Ian White/Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

When you can’t pay back your debts

Whether individuals, companies, or states, there are cases where, for various reasons, borrowed money cannot be repaid. When default occurs, if it is an individual or a company, they can choose “bankruptcy.” There are established legal safety nets, and anyone can undergo bankruptcy in accordance with fair procedures. If one liquidates assets to the maximum and repays creditors equally, no further liability is pursued. Debts that exceed one’s ability to repay are, simply put, written off. Of course, if a company goes bankrupt it can no longer continue as an organization, but an individual is not driven to starvation or death for the sake of repayment.

By contrast, even if a nation falls into default, there is no option of “bankruptcy,” and matters suddenly become opaque. Applying “bankruptcy” to a state as one would to a company would require eliminating the state’s very existence, which is impossible.

A state’s failure to pay its debts is called default, but there is no international legal framework governing what happens when default occurs. First, there is no higher authority above states that can wield power. Second, compared with individual or corporate cases, state “bankruptcy” would shift a relatively heavy burden of recovery onto creditors, making it difficult to adopt the same systems used in the private sphere. For these reasons, post-default procedures are highly ambiguous.

Because social credit is essential for future borrowing, even defaulting states generally do not wish to have their debts simply wiped out as in individual or corporate bankruptcies. Thus, states take the lead in seeking debt reduction and softer terms, but this is highly complex and negotiations typically take a long time. These negotiations drain both the state and its creditors.

Police guarding a bank in crisis-hit Greece (Photo: Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 2.0])

How vulture funds work and what’s wrong with them

With that background, let us look at how vulture funds operate. According to an report issued by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), a vulture fund in the strict sense is defined as follows.

“A private commercial entity that, for the purpose of profit recovery, acquires defaulted claims or distressed debt (debt issued by institutions in financial distress) through purchase, assignment, or other transactions.”

This article aims to interpret that in relation to states—that is, in connection with sovereign bonds issued by governments and government-related agencies. In this sovereign-bond context, vulture funds are often called “distressed-debt funds,” and they feast on the carcasses of poor countries as their main targets.

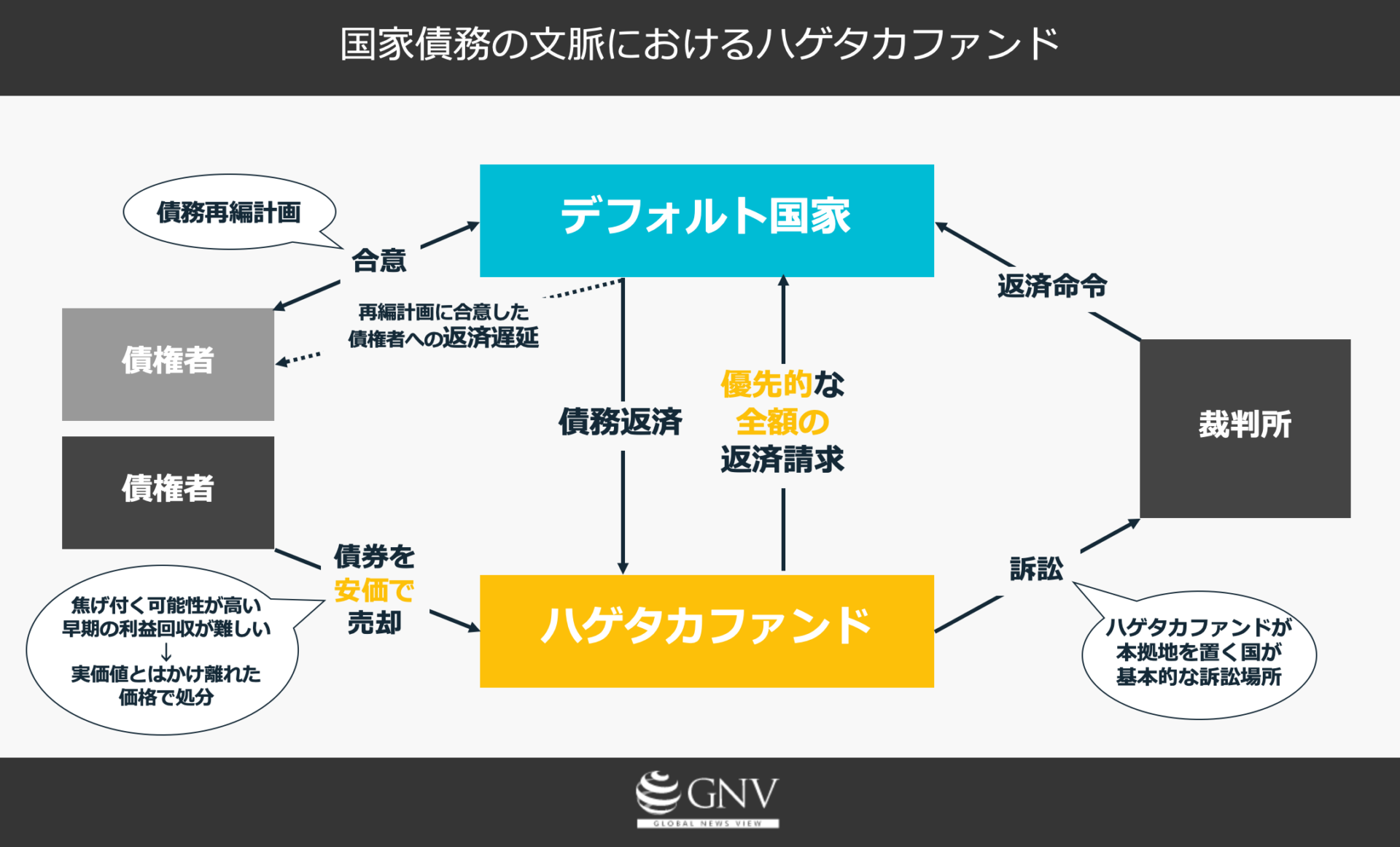

Here is how they operate. First, they acquire the sovereign bonds of a defaulted poor country on the secondary market at prices far below their true value. Once acquired, they use every method imaginable—lawsuits, asset seizure, political pressure—to pursue full repayment of the debt, together with interest, penalties, and incurred legal fees.

Seen this way, some might think, “They’re not collecting debts illegally,” or “Isn’t this normal in a capitalist society?” So what is the problem with vulture funds?

As noted, poor countries are the targets of vulture funds, and most of the countries they prey on are those known as Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPCs). In line with certain criteria regarding poverty and the severity of indebtedness, roughly 40 countries have been designated as HIPCs by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (we should not forget that more than 30 of them are concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa).

Because HIPCs need funding to alleviate poverty and foster development, there is a global movement to accept debt reduction and eased terms for these countries and to promote debt restructuring as relief.

In the first place, the debts borne by heavily indebted countries such as HIPCs are to a significant degree attributable to the creditor side—namely, advanced economies. Under the Cold War’s competing blocs, it was the advanced countries that lent large sums for strategic and political reasons to prop up dictatorships in Africa and Latin America. During and after the oil shocks, banks in advanced economies awash with petrodollars, protected by guarantees from their own governments, extended vast loans to developing countries without properly considering their repayment capacity. In other words, responsibility often lies not only with the debtor but also with the lender.

Moreover, much of the debt held by poor countries carries quite high interest rates (there are no clear global rules on interest for lending to states, and rates have historically been high compared to the private sector), and in some cases countries continue to pay only the accumulated interest even after the principal has already been paid off. Hence, it is in a sense natural that the creditor community as a whole accepts negotiations for restructuring or cancellation. Yet vulture funds run directly counter to this trend and seek to squeeze money from the poor.

Currencies of the world (Photo: Images Money/Flickr[CC BY 2.0])

Sovereign bonds of HIPCs in default are often hard to collect on, and when debt restructuring talks begin they can take a long time. In addition, recovery may be practically difficult. Consequently, among creditors seeking short-term returns or fearing a write-off, many give up on recovery when default occurs and try to offload the country’s sovereign bonds early to claw back at least part of the principal. Vulture funds seize this opportunity, which is why they obtain bonds at prices far below true value.

Having acquired sovereign bonds, vulture funds refuse restructuring plans agreed between the debtor state and the wider creditor group, and instead start demanding full repayment of the debt. This move, which stalls an orderly reconstruction, is called a holdout (※1), and ignoring the global trend to relieve heavily indebted poor countries is a serious problem.

Case: Argentina’s fight against vulture funds

Argentina fell into default in 2001—some readers may remember. At the time the country was saddled with a massive $81 billion in debt, and restructuring it was urgent for the nation’s survival. Although negotiations with creditors were fraught, by 2010 Argentina had reached an agreement to reduce its debt with over 92% of its creditors. One step remained to complete the restructuring. It was a ray of hope for Argentina, but NML Capital, a vulture fund under the major U.S. hedge fund Elliott Management, refused to go along.

Without participating in the restructuring agreement, they filed suit in U.S. courts demanding repayment from Argentina. They had scooped up Argentine sovereign bonds that hit the market at bargain prices amid fears of a write-off, and, ignoring the rescue effort, sought to reap windfall profits. The court ultimately sided with NML and ordered Argentina to repay a huge amount. Not only were the efforts of the other creditors completely ignored, but Argentina was required to prioritize repayment to NML ahead of them.

Protests against the vulture funds that attacked Argentina (Photo: Jubilee Debt Campaign/Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

In debt contracts, the principle of equal treatment is the global norm, and repaying only NML on preferential terms departs from that norm. Nevertheless, NML filed further motions in U.S. court to ensure Argentina would pay, imposing strict financial conditions on the country. Argentina, unable to withstand the resulting financial squeeze, had no options left. Exhausted by roughly a decade of legal battles with NML, it ultimately had to accept repayment.

The harm vulture funds cause

Argentina is not alone. Many poor countries, including Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have suffered at the hands of vulture funds. Over roughly 35 years from 1976 to 2010, around 120 repayment lawsuits were filed against 26 defaulting countries. Remarkably, this figure covers only cases in the United States and the United Kingdom; it excludes lawsuits elsewhere. Moreover, the lawsuits have a high success rate of 72%, revealing how poor countries are being squeezed by vulture funds.

In Africa, the region most targeted to date, an average of eight lawsuits per year are brought against defaulting states, and in some countries the total amount claimed represents 12–13% of GDP. At the same time, Africa’s win rate in such cases is low, and total payments have exceeded $700 million.

Once sued, enormous costs and time are required, and countries often end up having no choice but to accept payment orders, as Argentina did. Because revenues are diverted to debt service, funds that should go to public services such as hospitals and schools disappear, and the country does not grow wealthier. States facing short-term cash squeezes may be forced to sell public projects to the private sector, putting citizens’ living standards at risk. There is a vicious cycle centered on vulture funds.

Furthermore, when a payment judgment is handed down, repayment to creditors who accepted debt reduction is pushed to the back of the line, while repayment to holdouts like vulture funds is prioritized. Is it truly ideal that those who acted responsibly by accepting restructuring end up bearing the loss? The question defies easy answers.

The vulture funds’ cover

We have seen the problems with vulture funds that siphon wealth from poor countries, but are there no moves to counter them?

Protests against the vulture funds that attacked Argentina (Photo: Jubilee Debt Campaign/Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

There are, of course, such moves. In its 2014 report, the UN Intergovernmental Committee of Experts on Sustainable Development Financing (ICESDF) stated:

“Sovereign debt crises significantly impede countries’ efforts to mobilize financing necessary for sustainable development. They result in capital flight and devaluation, and in higher interest rates and unemployment. Effective debt management to avert debt crises is a priority. … (Regarding the debt crisis associated with Argentina’s default) the holdout by some creditors, in terms of delaying the country’s debt restructuring, is a matter of deep concern for both developed and developing countries.”

The harmful effects of vulture funds are clearly recognized.

Spurred by the efforts of Argentina and Greece, both suffering from debt crises, a proposal was made at the 2015 UN General Assembly to establish “a set of principles for sovereign debt restructuring processes” to resolve disputes between defaulted states and their creditors. There were 141 votes cast: 136 in favor, 6 against, and 41 abstentions.

The issue lies with the countries that voted against. Powerful creditor nations such as the United States, Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom opposed the measure. The European Union, despite strong pleas from Greece, maintained an abstention on this and all other items related to sovereign debt.

Behind the failure to solve the vulture fund problem is the opposition of advanced countries that block efforts to counter them. Some states have enacted domestic laws to restrain vulture funds, but in the so-called international community, it is hard to argue that the most influential countries are seriously committed to resolving the problem.

Advanced countries claim that setting rules for debt restructuring would inject uncertainty into financial markets, but is that truly an objective judgment free of self-interest? The adopted resolution is not legally binding. It is undoubtedly a big step forward, but at this pace a fundamental solution still seems far off.

Toward eradicating vulture funds

Vulture funds target poor countries and feed on those suffering under debt. Their repayments strain poor countries’ treasuries, but the fact that money that should be allocated to citizens is diverted to debt service is more serious than the words alone convey.

If adequate funds are not allocated to healthcare. If there is no investment in basic infrastructure such as water and electricity. Vulture funds are not just an economic issue. There is an ethical issue here that concerns human lives.

An Ethiopian child receiving a vaccine (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia/Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

As the majority at the UN General Assembly agreed, it may be necessary to establish an international framework for when a country falls into default. The principle of equal treatment among creditors should be made to function properly, and holdouts should perhaps be uniformly disallowed. The fact that there is no court-like body to handle sovereign defaults is also problematic. In any case, it is certain that the world as a whole—developed and developing alike—must work toward a solution.

As noted earlier, many of the debts borne by poor countries are ones for which advanced countries should also bear responsibility. At various historical moments—the Cold War, the oil shocks—who lent irresponsibly to dictatorships in Africa and Latin America for their own convenience? Debt restructuring proposed by defaulted poor countries is not merely for relief; rather, in terms of assuming due responsibility, it is something advanced countries ought to take the initiative on.

Poor countries suffering under debts of questionable legitimacy, and vulture funds seeking to spin further profits from those debts—this problem may reflect a distorted survival-of-the-fittest dynamic in the background.

※1:Opposing a debt restructuring plan and stalling an orderly reconstruction; also, creditors who engage in such behavior.

Writer: Tadahiro Inoue

Graphics: Tadahiro Inoue

「借金を返せなくなったら」の説明から入り、知識が乏しい私にも非常に分かりやすい内容でした。

以前のGNVの記事で紹介していた不法資本流出のように、世界の貧困は、立場の強い先進国が貧困国から利益を搾り取ろうとする構図に起因する部分がかなり大きいことに危機感を覚えます。

また、そういった貧困は先進国が生み出している構図に、先進国の人が気付いていないことも非常に問題意識を抱きます。

ハゲタカファンドによって苦しんでいる人々がいる中で、「デフォルトに陥った国と債権者との間における紛争を解決するための一連の原則」を設定する提案に日本も反対票を投じていることに衝撃を受けました。私たち国民としても何とかしなければならないなと思います。

とてもわかりやすい記事でした。

泥沼、というか悪循環にはまってしまっているような状況で、解決がなかなか難しそうですね。

先進国の利己的な姿勢が少しでもなくなっていけばいいのになと思います。

貧困国がなかなか発展できない理由の一つに、先進国によるハゲタカファンドがあることを知って驚きました。貧困の問題は先進国の影響が大きく、そのことを先進国の人々が知っていくべきだと思いました。国際的な機関がないので問題解決は難しいですが、貧困解決にお金を貸すのではなく寄付などがもっと必要だと思いました。

経済面からの問題提起とても面白かったです。

資本主義のなかでどうやって改善していけるんだろう、、