In August 2018, Mustafa Akıncı, the leader of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, stated that peace talks with the Greek Cypriot-led Republic of Cyprus in the south, which had been at an impasse, were expected to resume in New York from September of that year.

However, the resumption of the Cyprus peace talks should not be celebrated unreservedly. Located in the Eastern Mediterranean, the island of Cyprus has been divided for over 40 years since the 1974 ceasefire, with the northern and southern regions governed by different authorities. It is often called the “graveyard of diplomacy”, and despite early attempts at resolution through United Nations mediation, a way out remains elusive. This article explores from multiple angles what makes resolving the Cyprus problem so difficult, and whether a solution is possible.

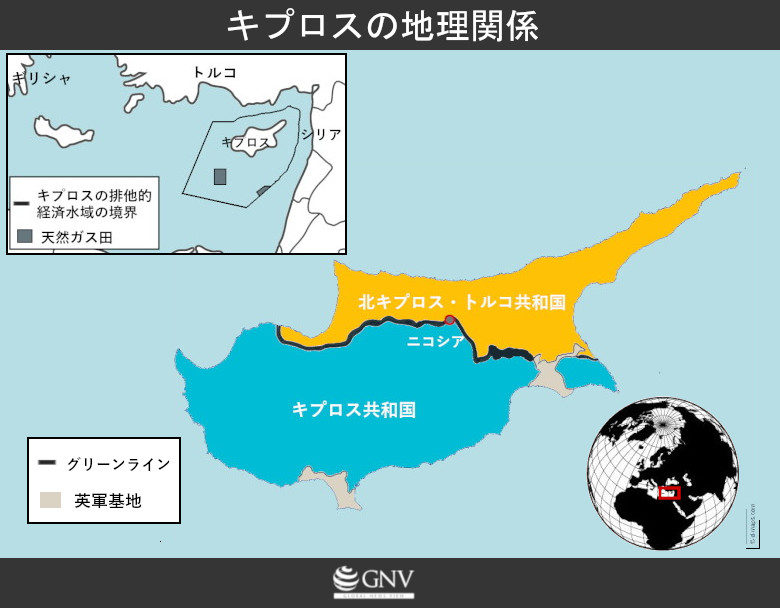

The Green Line dividing the capital, Nicosia (Heracles Kriticos/Shutterstock.com)

History of the conflict

The history of Cyprus’s division dates back to the late 19th century. From the time the island came under British control amid the decline of the Ottoman Empire, there was tension between Greek Cypriots, who mainly sought union with Greece, and Turkish Cypriots, who advocated maintaining independence from Greece and Turkey. In the late 1950s, Greek Cypriot residents launched a guerrilla campaign calling for independence from British rule and union with Greece. Subsequently, while recognizing the United Kingdom, Turkey, and Greece as “guarantor powers” under the Treaty of Guarantee, Cyprus declared independence from British rule based on a constitution promulgated in 1960, establishing the Republic of Cyprus. This constitution set out a balance between Turkish and Greek communities in the executive and legislature: specifically, the election of a Greek Cypriot president and a Turkish Cypriot vice president, and a 7:3 ratio between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots for civil servants and members of parliament. However, these provisions did not reflect the actual population ratio and were clearly disadvantageous to Greek Cypriots. As a result, Greek Cypriots grew increasingly dissatisfied, and large-scale intercommunal conflict broke out from 1963 to 1964.

The island’s division became definitive in 1974. In response to a coup d’état by a Greek Cypriot armed group backed by the Greek military junta, Turkey intervened militarily, citing the protection of Turkish Cypriot residents. As a result, Turkish forces and Turkish Cypriots took control of the northern one-third of the island, and about 160,000 Greek Cypriot residents were pushed to the south. Conversely, the influx of Turkish Cypriots from the south further entrenched ethnic division. Today, a UN-administered buffer zone known as the “Green Line” runs along the north-south boundary, dividing even the capital, Nicosia. The UN peacekeeping mission that began in 1964 continues to this day, conducting monitoring along the ceasefire lines and humanitarian activities. In 1983, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus was proclaimed, recognized only by Turkey.

Repeated breakdowns of peace talks

Since the late 1970s, peace talks have been conducted under UN mediation based on the principle of a “bi-zonal, bi-communal federation.” The main points of contention are fourfold. First is the political system, including whether to introduce a rotating presidency. Because the rotating presidency was among the causes of turmoil in 1963, it has been discussed with great care. Second is the return of property seized from Greek Cypriot internally displaced persons. The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus recognizes fewer than 70,000 as eligible for compensation, whereas the Republic of Cyprus claims 90,000, making agreement difficult. Third is the reduction and withdrawal of Turkish, Greek, and other troops that are still stationed on the island. Fourth is the status of the United Kingdom, Turkey, and Greece as guarantor powers. While the UK and Greece have agreed to relinquish their guarantor status as anachronistic in the 21st century, Turkey has consistently insisted on its right of military intervention as a “guarantor.”

Scene from the July 2017 Cyprus peace talks (far left: President of the Republic of Cyprus; center: UN Secretary-General António Guterres; far right: President of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus) (Photo: UN Geneva/Flickr【CC BY-NC-ND 2.0】)

External interests shaping the outcome

External interests make resolving the Cyprus problem even more difficult. Turkey, in particular, holds a key to a settlement. It asserts its right of military intervention as a “guarantor” and still stations around 30,000 troops in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. On the other hand, because a solution to the Cyprus issue is essential for Turkey’s long-standing goal of joining the European Union (EU), one could argue that Turkey has strong incentives to engage in the peace process. However, the discovery in recent years of large natural gas fields has undermined Turkey’s willingness to cooperate actively in the talks.

Among the successive discoveries of natural gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean in recent years is one found in February 2018 in the Calypso area off Cyprus. Believed to be very substantial, it has intensified the scramble for rights over gas fields around Cyprus. Based on its own interpretation of maritime law, Turkey insists these fields do not belong to the Republic of Cyprus and that it therefore lacks the authority to grant foreign energy companies rights to drill there, and has disrupted their drilling operations. Meanwhile, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus maintains that development of the gas fields should be postponed until a unification agreement is reached.

Another energy issue in Cyprus is electricity supply. To reduce dependence on Russian energy, the EU is reportedly considering integrating Cyprus into the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity. To do so, it would need to connect with Turkey’s power grid. Some argue that cooperation on electricity supply would help improve relations between Turkey and Cyprus. At the same time, voices in the Republic of Cyprus express concern that for political reasons the stability of supply could be threatened, making such an arrangement worrisome.

Protective dome for aircraft radar installed at a British military base (Photo: Paleo Straty /Shutterstock.com)

Alongside natural resources and electricity, the island’s value as a strategic military hub in the Middle East complicates a resolution of the Cyprus problem. In fact, the UK still maintains military bases on both sides of the island. In April 2018, it also participated in airstrikes carried out as sanctions in response to suspicions of Syria’s possession of chemical weapons, using its bases in Cyprus. A pro-Erdogan Turkish newspaper reported that countries including the UK and Greece were using the Syrian conflict as a pretext to maintain their presence in the Eastern Mediterranean, and that to counter such moves Turkey planned to build a naval base in Cyprus.

Potential for religious and social mediation

As noted earlier, with the limits of political mediation increasingly evident, new forms of negotiation have begun to be proposed and implemented to complement it. One involves bringing in religious leaders. In September 2015, with the full cooperation of the Swedish ambassador, the leaders of the Greek Orthodox Church (followed by most Greek Cypriots), Islam (followed by many Turkish Cypriots), and the recognized minority denominations of the Catholic Church, the Armenian Church, and the Maronite Church, together with the presidents of both communities, met to promote the peace talks.

A church and a mosque side by side (Photo: Terpsichores /Wikimedeia[CC BY-SA 3.0 ])

Social mediation has also been considered. Under the supervision of a completely neutral third party, consensus would be reached through direct or indirect interaction between citizens of the two communities at the grassroots level. People would share their fears and the injustices they have experienced, and citizens themselves would act as negotiators to discuss solutions. Although a referendum is indispensable to resolving the Cyprus issue, citizens have had no opportunity to express their will during the negotiation stage, which is seen as a reason agreements have not been reached. Some argue that invigorating debate in civil society about reunification could break this impasse.

Outlook

For more than 40 years, the island of Cyprus has remained divided despite the absence of large-scale fighting. The discovery of natural gas fields; the involvement of Turkey, Greece, and the UK; compensation for internally displaced persons; and the system of governance are among the complex domestic and international factors that hinder a solution, leaving political peace talks at an impasse. New forms of negotiation must be introduced, and a compromise that properly reflects the voices of citizens in both communities must be devised without delay.

Writer/Graphics: Hinako Hosokawa

Follow here → Twitter account

とても勉強になりました。色々な面からキプロス島をみていて面白かったです。

キプロスという小さな島全体での一体感や、ヨーロッパもしくはトルコ(?)への帰属意識はないのですか?

世界中の紛争や対立には、必ずイギリス、アメリカ、ロシア、EUあたりが関与してるね。基地の設置はイスラエルとか他のもっと大きな利害のためであって、南キプロスのために設置してるのではなくて南キプロスを利用してるんでしょ。トルコの背後はロシアかな?シマ争いや利権争いの背後に大国の大きな利害が関与してるのがよくわかる。

世界中のいろんな紛争、対立、もちろん日本も戦国時代いやもっと大昔から、こういう他の地域の利害と関与が絡んでるのを推測したり知るのは大事ですね。