In June 2018, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki held talks in Eritrea’s capital, Asmara, reaching a peace agreement with Eritrea after decades of conflict and confrontation, and achieving normalization of diplomatic relations.

Ethiopia is now approaching a major turning point. With the rise of Prime Minister Abiy, sweeping policy shifts have been introduced, and peace with Eritrea is only one part of them. Ethiopia faces many challenges, including domestic regional tensions. Can Abiy become the country’s savior? With the recent history of Ethiopia as background, we examine Abiy’s sweeping reforms.

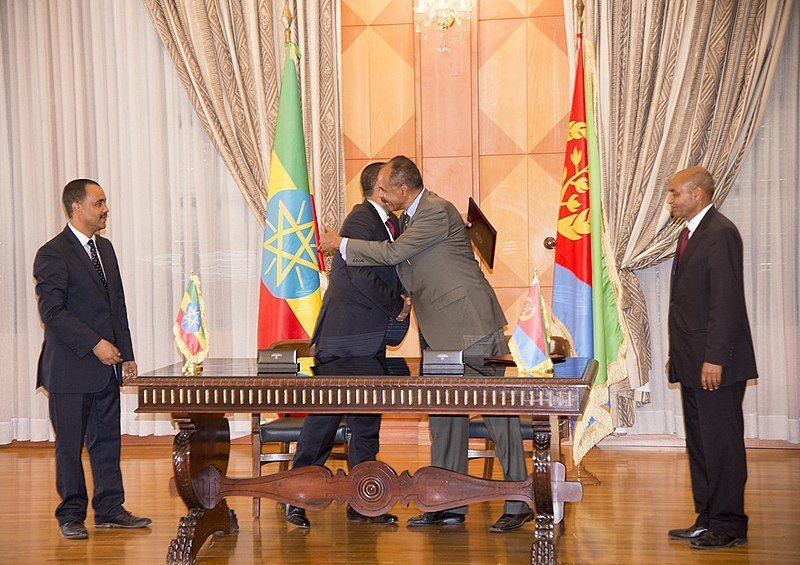

The presidents of Ethiopia and Eritrea embrace after the peace deal (Photo: Yemane Gebremeskel via Wikimedia)

Ethiopia’s fragile unity

In 1974, following the Ethiopian Revolution, Mengistu Haile Mariam seized power as chairman of the Provisional Military Administrative Council. At that time, Ethiopia, which had been supported by the United States, shifted its alliance to the Soviet Union and began receiving extensive aid. Mengistu abolished the monarchy and moved to socialism, imposed dictatorial rule and purges, and offered no relief during the famines of the 1980s—events through which hundreds of thousands of lives were lost. In 1987, with the establishment of the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Mengistu became president and instituted a one-party dictatorship under the Workers’ Party of Ethiopia.

Several groups rose up against this regime. Eritrea, which had been annexed as part of Ethiopia, saw the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) wage armed struggle against the government since 1961 in pursuit of independence. The Oromo, the largest ethnic group representing one-third of the population, formed the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) as a resistance force against the Mengistu regime. Similarly, Tigrayans formed the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and carried out anti-government activities.

Around this time, neighboring Somalia claimed the Ogaden region in eastern Ethiopia, inhabited mainly by Somali people, as its own territory. In 1977, its invasion to reclaim this territory triggered the Ogaden War.

However, the Soviet Union, which had also supported Somalia, chose Ethiopia, and Cuban forces joined in support. The United States then provided military aid to Somalia, but Somalia lost the war in 1978. Thereafter, Somali inhabitants seeking secession from Ethiopia formed the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) and continued to resist the government. In suppressing these rebellions, the government committed numerous human rights abuses. This state continued even after the Cold War. Yet these conflicts cannot simply be dismissed as “ethnic conflicts”; in many cases, struggles over power and scarce water resources and land underlie them.

A monument to those who died in the Ogaden War, erected during the Mengistu regime (Photo: Tim Mansel [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ])

Ethiopia after the Cold War

By the late 1980s, as the Cold War was ending, the Mengistu regime weakened as Soviet military aid dried up. At the same time, the Tigrayan TPLF secured the cooperation of the EPLF by promising Eritrean independence, and in 1991 they toppled the long-standing dictatorship. After the fall of Mengistu, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of anti-government forces centered on the TPLF, took power as the ruling party. Ethiopia’s new system, based on a federal structure divided into ethnically based regions, was established, and in 1993, as initially promised, Eritrean independence was recognized. In 1995, with a new constitution, Meles Zenawi—who had formed the TPLF and served as interim president of the EPRDF—became prime minister, and the country was renamed the “Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.”

Although Eritrea had ostensibly gained independence from Ethiopia smoothly, relations deteriorated over border demarcation, trade, and diplomacy. In 1998, an armed clash over sovereignty of the border area of Badme escalated into full-scale war. The Ethiopia–Eritrea border war killed at least 70,000 people. A ceasefire was brokered by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), and a peacekeeping force (PKO: UNMEE) was deployed along the border. A third-party boundary commission decided that Badme belonged to Eritrea, but Ethiopia refused to accept this and continued de facto control. As a result, hostilities persisted and diplomatic relations remained severed until 2018.

Citizens who had fled the war return from Eritrea to Ethiopia under the guidance of the PKO (Photo: UN Photo by Rick Bajornas)

Even after the transition to the Meles administration, various domestic conflicts continued. The ruling EPRDF comprised four organizations— the TPLF representing Tigray, the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), and the Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM)—but in reality, the Tigrayan TPLF, which accounted for only about 6% of the population, effectively dominated politics. Numerous human rights abuses by the government continued in Oromia, the Ogaden region, and Amhara. As a result, in Oromia alone, by 2017 at least 700 people had been killed and thousands imprisoned.

Furthermore, in 2014 the ruling EPRDF announced the expansion of the capital, Addis Ababa, which is surrounded by Oromia. In response, dissatisfaction in Oromia, the most populous region, deepened further, and anti-government protests demanding political freedom and social equality intensified.

The rise of Prime Minister Abiy

In 2012, following the death of Prime Minister Meles, Hailemariam Desalegn of the SEPDM assumed the premiership. Responding to the surge in anti-government movements centered in Oromia, Amhara, and the Ogaden region, he sought to calm the situation by releasing political prisoners and shutting down prisons where torture had occurred. However, repeated re-arrests prevented reconciliation with opposition forces, and his political and economic reforms were blocked within the ruling party by the Tigrayan faction; Hailemariam announced his resignation in 2018.

His successor, Abiy, became the first prime minister from Oromia. Beyond his Oromo origins, Abiy has a diverse background, with a Muslim father and an Ethiopian Orthodox mother, and he speaks the languages of the Oromo, Amhara, and Tigray peoples that make up the ruling coalition. In his April inaugural address, he apologized for past administrations’ killings of opposition forces and signaled a commitment to democracy by welcoming public dissent. In this way, Abiy is pursuing major policy shifts and seeking to reform the political order. How is he tackling the various problems? Let’s look more closely at Abiy’s reforms.

Prime Minister Abiy (left) shakes hands with IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde (right) (Photo: International Monetary Fund [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Will Abiy’s reforms resolve Ethiopia’s political problems?

The emergence of Abiy, the first Oromo prime minister, served as a salve for political discontent in Oromia. He is seeking to advance political reforms that address Oromo grievances against Tigrayan dominance. In addition, to prevent a re-concentration of power, he plans to amend the constitution to apply term limits to the prime minister. These reforms have been welcomed in Oromia, easing discontent, reducing protests, and enabling the lifting of the state of emergency.

Abiy is also aiming for peace in the Ogaden region by abolishing prisons where political prisoners were tortured and by concluding a ceasefire. This is expected to bridge the long-standing divide between Somali communities and the Ethiopian government.

Abiy also moved to make peace with Eritrea, the most intense external rivalry. He announced a historic “Declaration of Peace and Friendship” to end the Ethiopia–Eritrea border dispute, and in June 2018 he held talks with President Isaias in Asmara. In the meeting, both sides agreed that Badme would belong to Eritrea, and peace was established. In addition, diplomatic relations were normalized, and with border crossings such as Bure reopened, landlocked Ethiopia—previously able to access the sea only via Djibouti—now has routes through Eritrea as well. Families separated by the border have reunited, and telephone service and flights between the two countries have resumed; the benefits are substantial and the mood on the ground is celebratory. The peace with Eritrea is also expected to have various impacts across the Horn of Africa, including Somalia, Djibouti, and Sudan.

Participants in a women’s marathon held in Addis Ababa under the theme “A Life Without Violence” (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ])

Remaining challenges

Despite continued positive headlines, many challenges remain in Ethiopia.

Not all citizens welcome Abiy’s rise and reforms. On June 23, a grenade was thrown into the crowd at an Abiy political rally, killing one person and injuring 153. While Abiy seeks to energize a multi-party democracy, the ruling party may not be able to maintain its vote share while coexisting amicably with the opposition. In the upcoming 2020 elections, the anticipated redistribution of seats could lead to friction and confrontation.

Even in Oromia, where the effects of Abiy’s rise were most anticipated, many problems remain. Some Oromos are separatists seeking independence from Ethiopia and view Abiy as a traitor. Moreover, in September, exiled OLF leaders and 1,500 fighters returned to Ethiopia, triggering clashes in Addis Ababa that left 23 people dead.

Institutions such as the legal system and police have long been subject to interference under non-democratic rule; ensuring their neutrality and strengthening the rule of law are tasks ahead. Economically, Ethiopia carries heavy foreign debt and faces severe inflation. In response, the government has begun economic reforms such as market liberalization and privatization of state-owned enterprises; whether these will succeed in revitalizing the economy will be key.

Addis Ababa: Can the economy be revitalized? (Photo: Ninara [ CC BY 2.0 ])

In Ethiopia, overlapping interests among neighboring countries and ethnic groups fueled prolonged conflict and instability. Yet in this context, Prime Minister Abiy has charted a new course for the entrenched political system and economy, which had seen little reform. As a first step, he has rapidly achieved progress on long-standing issues such as easing the Oromo question and making peace with Eritrea—making him a great hope for the Ethiopian people.

At the same time, many challenges remain. Can Abiy meet the public’s high expectations and become a savior? We look forward to further transformation toward a better country and region.

Writer: Yutaro Yamazaki

Graphics: Hinako Hosokawa

知らないことだらけでした。でも旧ユーゴのように、一人の英雄の存在と功績が大きすぎると、アビーが死んだらまた問題が浮き彫りになりそう。

わかります。でも、首相になったばかりで、まだまだ不安定が続いてます。旧ユーゴのTitoみたいに、アビーがエチオピアを抑えきるのも難しそう。うまいこと国内の各勢力をゆるくバランスさせるのが精一杯、という形になるのでは。

今年の潜んだ10大ニュースの1位に選ばれましたね!

//globalnewsviewdotorg.wpcomstaging.com/archives/8825

おめでとうございます!