Colombia had begun to open a path toward peace with the 2016 peace agreement. In May 2018, a presidential election was held in which former armed groups participated for the first time as a political party. However, in Colombia after the peace deal, both former armed groups and the new president are dissatisfied with the contents of the agreement, raising the possibility of backsliding rather than progress. In areas formerly controlled by the armed group, new factions continue to gain strength. What will become of the peace agreement and of Colombia? Let’s look at the situation in Colombia.

Ceremony of the 2016 peace talks between the Colombian government and FARC (Photo: Gobierno de Chile / Flickr[CC BY 2.0])

The road to the peace agreement

In Colombia, from the late 19th to the 20th century, in order to pay off national debt the state sold vast tracts of land to individuals and foreign companies establishing plantations, allowing a small elite to own huge estates and creating deep inequalities with peasants. Around that time, in 1964, in an effort to confront domestic inequality, peasants and rural laborers founded FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) (※1). FARC’s founders created agricultural communes and took other steps to rescue peasants from inequality, but influenced by the Cuban Revolution of the 1950s, they came to demand more rights and land. These actions were seen as a threat by large landowners and the state, and a 52-year war with the Colombian government ensued. This conflict claimed 220,000 lives and forced some 7 million people to flee their homes and become displaced.

FARC soldiers (Photo: Andrés Gómez Tarazona / Flickr[CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Also in 1964, another group aiming to confront Colombia’s unequal distribution of land and resources, the ELN (National Liberation Army) (※2), was founded. Arguing that the country’s oil and mineral resources should be shared by Colombians rather than other countries, it has carried out attacks against large landowners and multinational corporations.

Furthermore, drug trafficking became a major problem from the 1980s. In areas controlled by FARC and ELN where the government’s authority didn’t reach, lucrative illegal cocaine production flourished. At the same time, in order to counter FARC and ELN, paramilitary groups such as the AUC (United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia)(※3), which cooperated with the government, foreign companies, and large landowners, also expanded their power and became heavily involved in the drug business. Cocaine produced in Colombia is smuggled to the United States via the Northern Triangle of Central America and other routes, forming a south–north trafficking corridor across the Americas. As a result, transnational criminal organizations operate in the Northern Triangle, making it an area with poor public safety. Armed groups enriched by the cocaine trade also operate, adversely affecting other regions of the Americas.

In 2012, former President Juan Manuel Santos declared his aim to achieve peace in Colombia, and peace talks began between the government and FARC. These talks primarily addressed agrarian reform to allocate unused farmland to peasants and FARC’s disarmament. With the United Nations set to monitor implementation of the agreement and FARC’s disarmament, in September 2016 former President Santos and FARC leader Rodrigo Londoño signed a peace agreement in Cartagena in northwestern Colombia. However, there was opposition, including from former President Álvaro Uribe, and the peace deal was ultimately put to a national referendum. In the referendum held that October, the agreement failed to win the support of a public that had long suffered FARC attacks, and many felt the terms were too favorable to FARC, resulting in a majority voting against it. Nevertheless, in November of the same year, a revised peace accord was approved by Colombia’s Congress.

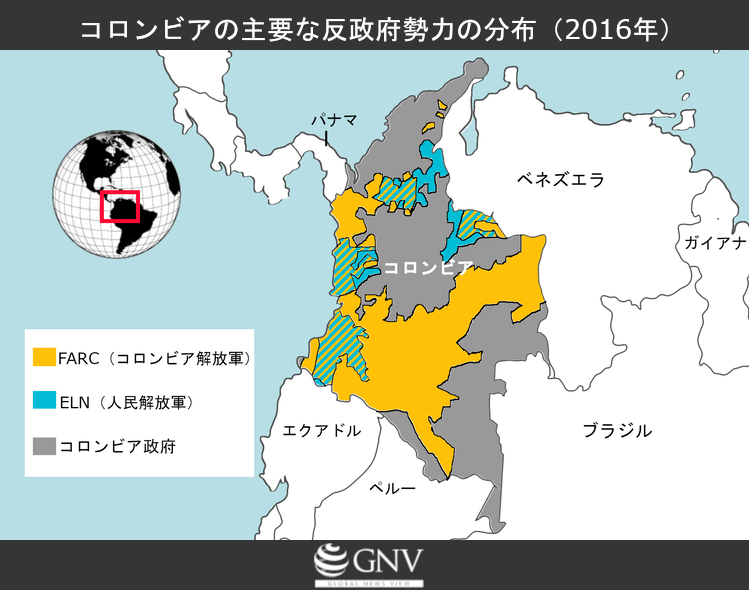

Created based on Al Jazeera map data

As a reflection of the peace agreement’s provision calling for political participation by demobilized former FARC fighters, a few months after the deal FARC became a political party. It kept the acronym FARC but changed its meaning to FARC (Common Alternative Revolutionary Force) (※4). It fielded candidates in the March 2018 legislative elections, and in the May presidential election former FARC leader Londoño ran for president.

Colombia after the peace agreement

In 2017, one year after the peace accord, more than 12,000 FARC combatants pledged to return to civilian life and handed over about 8,994 guns and weapons to the United Nations. As a result, compared to 2002, when the conflict was at its peak and 3,000 people were killed, the number of deaths fell to under 100, and the number of displaced people dropped by 79%.

The government provides former FARC members who disarmed with $215 per month to help them return to civilian life.

International support also increased. In 2016, to help implement the peace agreement, the EU provided about €96 million in funding, and further approved an additional €15 million to strengthen and implement the accord. This money is intended for revitalizing economic activity and rebuilding areas affected by the conflict.

Former President Santos visiting Europe to seek aid (Photo: Martin Schulz / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Problems remaining after the peace agreement

However, much of the peace accord has not been implemented, and drug production and export and the use of force continue in Colombia.

Regarding armed violence, talks on peace with the ELN have not progressed. Peace talks had been held in Ecuador since February 2017, but in January 2018 ELN members carried out attacks that killed seven people and injured more than 40, prompting government condemnation and a six-week suspension of the talks. The ELN, seeking social change to achieve equality for the people, is in no hurry to reach an agreement, unlike the government.

In former FARC-controlled areas after its disarmament, other armed groups and gangs have taken over. A particularly serious problem now is Mexican drug cartels. For example, Tumaco in southwestern Colombia has seen some of the country’s worst ongoing violence, as groups that have moved in to tap into revenues in areas where FARC used to profit battle for control. Tumaco is also the largest production area for coca, the raw material for cocaine. In 2016 it reached 188,000 hectares. Because it is more profitable than other crops, poor farmers illegally cultivate coca. According to the Colombian government, national income from cocaine amounts to about $13 billion per year.

Over this cocaine trade, Mexican cartels that transport and deal drugs from Colombia to the primary consumer, the United States, are expanding into areas vacated by FARC. These cartels obtain cocaine through local gangs. Meanwhile, former President Santos, to build support for the peace accord, promised troops and investment in former FARC-controlled areas and sought to end coca cultivation and increase national income from other crops. However, weakened economic conditions made funding difficult, and there was strong opposition to halting coca cultivation, even leading to riots. Today, Mexican cartels and 70 armed groups and gangs still operate in the country.

Colombian military burning a cocaine factory (Photo: Policía Nacional de los colombianos / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

There have also been attacks on local leaders and human rights defenders. Between January 2016 and July 2017, more than 186 social leaders and human rights advocates were killed. Such crimes occur frequently in former FARC strongholds where many armed groups operate and government control is weak. Without government protection, leaders in these areas live in constant fear of death.

In the 2018 election campaign, FARC participated as a political party, but faced obstruction—Londoño was attacked—and they suspended campaigning. Many voters have long suffered FARC attacks, making it difficult for the party to win support. Government assistance has not reached far, and the peace deal’s aim of enabling former FARC members to participate in politics as members of society has not been realized. It is not yet a safe environment for former combatants to return to civilian life.

The future of the peace agreement under the new administration

In 2018, elections were held in which FARC participated for the first time as a political party. In the final results of the June presidential election, Iván Duque, who opposes aspects of the peace agreement, won 54% of the vote, defeating Gustavo Petro, who supported the deal, and was set to become the new president in August.

Duque, elected as the new president (Photo: InterAmericanDialogue / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Duque ran with the support of former President Uribe of the Democratic Center, who opposed the peace deal. Arguing that the accord is too lenient on former FARC combatants, he has called for renegotiation to include provisions that punish wartime crimes. These include restricting the liberty of former FARC combatants convicted of war crimes for up to eight years; trying former combatants involved in war crimes in Colombia’s Supreme Court; and barring armed group members responsible for war crimes from holding public office until they pay sanctions.

However, since the peace agreement took 19 months to conclude, changing it could lead to a situation where armed groups take up arms again. Under the deal, from 2018 to 2026, regardless of election outcomes, the FARC party is guaranteed five seats each in the Senate and the House. But if Duque’s campaign pledge to bar those involved in war crimes from holding office until they pay sanctions is implemented, this could change, raising concerns that leaders may leave demobilization zones with their fighters and form new armed groups.

Duque also insists he will not conduct peace talks with the ELN except under certain conditions, such as ceasing all criminal activity, international monitoring, and setting a timetable for negotiations. The ELN wants to continue talks but shows no sign of accepting these conditions. This is likely to hinder the elimination of armed conflict within Colombia.

The struggle between armed groups and the government lasted 52 years, the longest in South America. FARC has disarmed, become a party, and is trying to abandon violence and participate in democracy. Will the government side be able to stay on the path to peace? With Duque’s election, the peace accord may be downplayed, increasing the likelihood that the agreement built by former President Santos will not be implemented. Although the peace deal ended the internal conflict, various problems remain due to insufficient implementation amid weak governance and worsening public finances, and the transition to a president who opposes the accord is pushing Colombia back toward the pre-agreement period. The fate of peace in Colombia may rest with the new president, Duque.

Cartagena, a Colombian city on the Caribbean Sea (Photo: R. Halfpaap / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

※1:Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia

※2:Ejército de Liberación Nacional

※3:Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia

※4:Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común

Writer: Saki Takeuchi

Graphics: Yuna Takatsuki

コロンビアは麻薬とギャングの温床だというイメージをもともと持っていましたが、どういう経緯で治安が悪くなってしまったのかがよくわかりました。和平合意後も残る課題解決のために、他の国々がなんらかの形で助けることができたらいいなと思います。

大土地所有制による不平等の解消は難しいんだな、、と痛感しました。

実態を伴った、持続的な和平が進んでほしいです。

コロンビアの和平合意に関する国民調査に先立って行われた世論調査では、賛成派が反対派を大きく上回ったという話を聞いたことがあります。実際ところ、国民は和平をしぶる人が多数なのでしょうか…?