In November 2017, Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, while staying in the foreign land of Saudi Arabia, suddenly announced his resignation. He cited Iran’s involvement in Lebanon and threats to his life, but because the development was so abrupt and unnatural, foreign media gradually coalesced around a different narrative. Hariri had originally been scheduled to go on a desert camp trip with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed. However, according to one investigation, his mobile phone was suddenly confiscated, he was separated from his bodyguards, and forcibly handled by Saudi security officers; ultimately, he was handed a prewritten resignation speech and reportedly forced to deliver it in front of Saudi television cameras. Furthermore, even after announcing his resignation, he was unable to return home, strengthening the view that the Lebanese prime minister had effectively been abducted by Saudi Arabia. Both Hariri himself and Saudi Arabia denied this, but suspicions have never been fully dispelled. Why did such a thing happen? How are neighboring countries involved? Let’s take a closer look at Lebanon.

Prime Minister Saad Hariri (Photo: kremlin.ru [CC BY 4.0])

Lebanon’s political system

Located at the crossroads of the three continents of Asia, Europe, and Africa, Lebanon lies geographically close to centers of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, making it a country of multiple ethnicities and sects. It has as many as 18 sects, including Muslim (Shia, Sunni, Druze) and Christian (Maronite, Greek Orthodox, Catholic, Armenian Orthodox), among others. Amid competing identities, measures to maintain stability have produced an unusual sect-based parliamentary structure: the constitution allocates the number of parliamentary seats according to the size of each sect. By convention, the president is always Christian, the prime minister Sunni, and the speaker of parliament Shia, and parliamentary seats are pre-divided into 64 for Muslim groups and 64 for Christian groups.

Lebanon after independence and its neighboring countries

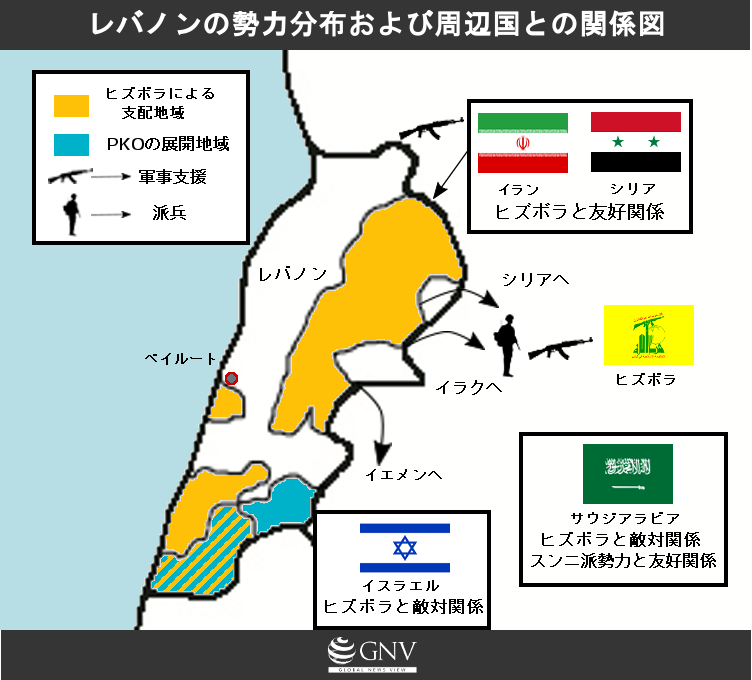

Lebanon’s situation cannot be understood solely through domestic sectarian conflict; it must be viewed in the context of the wider region. Each domestic force has historical, religious, and political ties with neighboring states, creating instability. From here, we will look at Lebanon’s relations with the countries that surround it.

In 1943, Lebanon gained independence from the French Mandate, but borders drawn without regard for religion or ethnicity and a complex ethnic makeup left a weak sense of national identity. The precarious political balance that had been maintained was disrupted by successive Middle East wars and by the relocation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to Lebanon after its expulsion from Jordan in 1970. As a result, confrontation between the Christian Maronite forces and the PLO intensified, while Muslim forces split into Shia and Sunni, each forming militias and fighting one another. In addition, under the pretext of removing the PLO stationed in southern Lebanon, Israel, which had been looking for an opportunity to intervene since the 1970s, invaded, further intensifying the conflict.

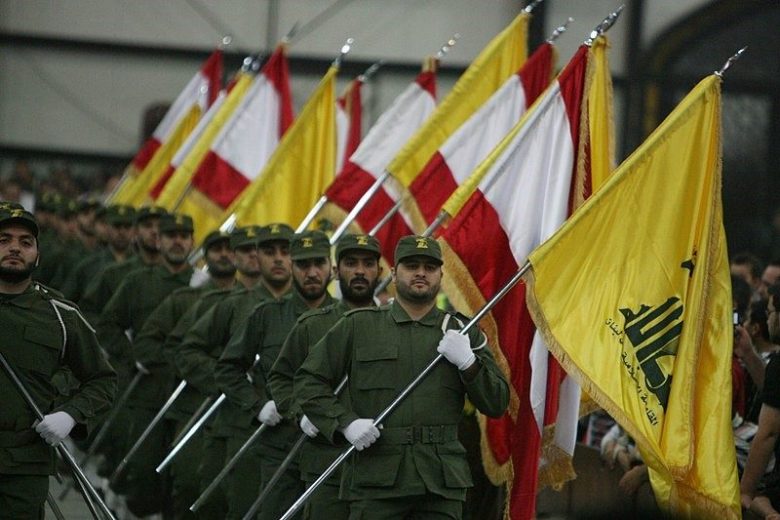

In 1982, Israel launched a full-scale invasion and occupation of southern Lebanon, prompting the PLO, Syria, Iran, and others to support Lebanon’s Shia forces. In that process, the Shia political-military organization Hezbollah emerged to resist the Israeli occupation. Hezbollah has especially close ties with Iran, receiving substantial weapons and support. Surrounding Lebanon, Syria sent in troops from 1976 to secure its own security and influence, becoming a party to the conflict. Another regional power deeply involved in Lebanon is the Sunni Saudi Arabia, which, since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, has viewed Iran as a regional rival, growing increasingly confrontational. Saudi Arabia seeks to influence Sunni forces and strongly criticizes Hezbollah. To help maintain regional peace and stability in this context, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), consisting of 15,000 personnel, was deployed along the Israel–Lebanon border area and remains in place today.

The Lebanese civil war ended in 1990; Israel withdrew in 2000, and Syria withdrew in 2005. However, the confrontation between Hezbollah and Israel continued, and in 2006 Israel invaded again, destroying much of southern Lebanon. Despite this, Hezbollah significantly expanded its influence in Lebanon and now possesses greater military capability than the Lebanese Armed Forces. It has also made major strides in politics, education, and healthcare, and in areas where it operates it is even described as a state within a state, in some places exhibiting greater governing capacity than the Lebanese government. While there is currently no armed conflict in Lebanon, numerous destabilizing factors remain, including external influences from neighboring countries.

Hezbollah military parade (Photo: khamenei.ir [CC BY 4.0])

Lebanon’s current situation

As the Arab Spring that began in Tunisia in 2010 spread across North Africa and the Middle East, a new destabilizing factor emerged for Lebanon: the Syrian conflict. Surrounded by Syria, Lebanon began receiving Syrian refugees, whose number has exceeded one million—about one quarter of Lebanon’s population. It goes without saying that such a rapid demographic change has had a major impact on Lebanon’s society and economy. Classrooms have become insufficient, the burden on public services such as healthcare has grown, infrastructure works like road maintenance have stalled, and overall, the cost of supporting refugees has strained the economy.

Syrian refugee children attending school (Photo: DFID [ CC-BY-SA-2.0])

Government corruption has also reached a serious level. Politicians attempt to buy votes by bribing citizens, while corruption in infrastructure processes and an inefficient bureaucracy have reduced market competition year after year. The electricity system is one example. Power outages occur daily in Lebanon, and many citizens have to purchase very expensive generators to keep their homes lit. Although the public is calling for infrastructure improvements, the businessmen who run these generators are often connected to factional leaders, making the problem difficult to fix. A vicious cycle persists in which patronage is prioritized, public works stall, and citizens become even more disillusioned with politics. Investment has declined sharply due to conflict, political turmoil, and fears of IS (Islamic State) incursions from neighboring Syria.

Thus, Lebanon’s economic situation is dire due to the large influx of refugees, political corruption, and declining investment. As citizens face increasingly difficult lives, the number of people leaving for Europe shows no sign of slowing.

Lebanon devastated by Israeli airstrikes (2006)) (Photo: M Asser [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Lebanon’s first election in nine years

Because of the Syrian conflict and the resulting refugee crisis, parliament’s term was extended twice, and the general election held in May 2018 was the first in nine years. Voter turnout was about 49%, down from the previous 54%. The Sunni party of Prime Minister Hariri, who lost credibility over the resignation saga, lost seats, making him the loser of this election. By contrast, Hezbollah and its allied coalition made major gains, winning more than half the seats—67 out of 128. Even if Hariri remains the Sunni prime minister, he will likely be unable to take a tough stance against Hezbollah. Hezbollah is currently involved in the Syrian conflict on the side of the Assad regime, having significantly contributed to suppressing opposition forces, and it has also sent fighters to Iraq and Yemen. Iran is cooperating with Hezbollah, and the Lebanese government must find ways to coordinate with Hezbollah, which has stronger military power than the Lebanese Armed Forces and significant political clout.

Prime Minister Hariri, who suddenly announced his resignation in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, later returned home and withdrew it. However, it is believed that Saudi Arabia, wary of Shia Iran’s presence, was infuriated by the Sunni Hariri’s overtures toward Hezbollah and pressured him to resign. Today, Iran is using Hezbollah’s rise in Lebanon to expand its influence through neighboring Iraq and Syria to Lebanon, while Saudi Arabia is resorting to such hardline measures to resolutely resist and strengthen its own influence. In the Middle East, the power struggle between Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran is becoming ever more intense. When will Lebanon be freed from the influence of surrounding countries and become a stable multiethnic state?

A port town in Lebanon (Photo: Paul Saad [ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Writer: Mizuki Uchiyama

Graphics: Hinako Hosokawa

日本にすむ私たちには想像も理解も難しいくに、地域の問題についてわかりやすい図、写真、文章で読みやすい記事でした。

他の国のトップを「拉致」して辞任させても、他国からの批判がほとんどない状態は不思議で仕方がない。

サウジアラビア国内の恐ろしい人権侵害もそうだが。

サウジアラビアは、石油を大量に売る国、武器を大量に買う顧客。

アメリカ、ヨーロッパ、日本などから批判されなくて済む力になっている。

他の日本語メディアからはなかなか得られにくい地域についての情報がよくまとまっており、いつも感心しております。

イエメンでもサウジアラビアとイランが介入して対立してたけど、本当にサウジアラビアとイランは中東のあらゆる政治に関与してるなあ…