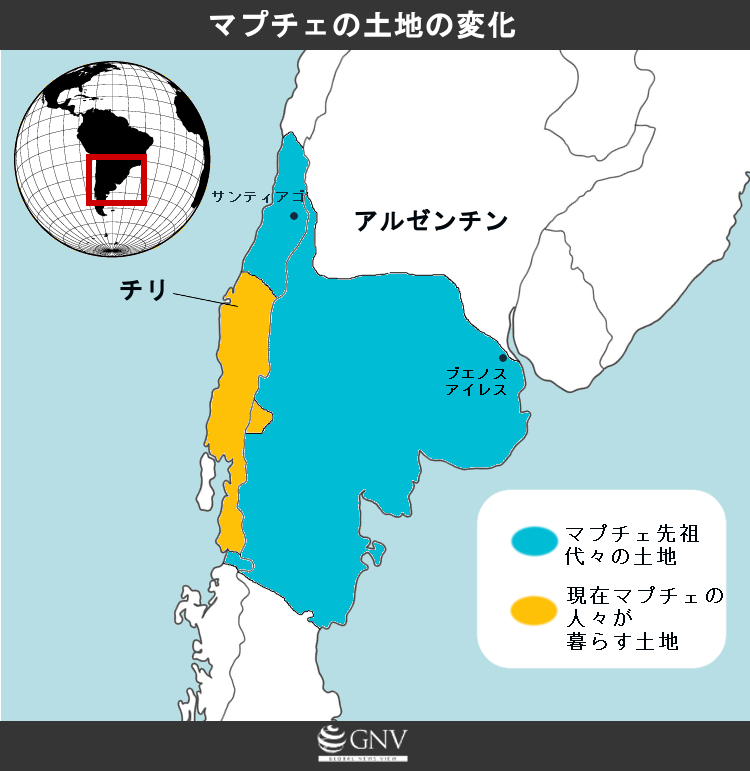

Have you ever thought about how people feel when they are forced off the lands where their ancestors have lived for generations? The rights and territory of the Mapuche, an ethnic group living from central-southern Chile to southern Argentina, have been continually threatened. As shown in the figure below, the Mapuche have been compelled to move from the lands where they have long lived. All of this has been unjustly taken by the governments of Argentina and Chile. Beyond seizing their land, both governments have failed to protect rights that should be safeguarded. Let us look at the current situation surrounding the Mapuche.

Created with reference to data from World Encyclopedia and Stratfor

The Mapuche and a history of invasions

The Mapuche are Indigenous peoples of the Americas who live from central-southern Chile to southern Argentina. They speak their own language, Mapudungun, and “Mapuche” means “people (Che) of the land (Mapu)” in Mapudungun. According to Chilean statistics, the Mapuche population is 604,349, about 4% of Chile’s total population. On the Argentine side, roughly 300,000 people live in the Andes. Historically they have made a living through agriculture and livestock, but in recent years more have moved to urban areas, with many working in educational institutions. Many Mapuche women living in cities work as domestic workers. As a tradition, they practice nature worship through musical performance. Their metalwork is renowned and used for accessories such as head ornaments like those in the photo below. Today, only a small number of people wear traditional clothing in everyday life; many wear it only for events such as weddings.

Mapuche women and children in traditional dress (Photo: Ministerio Bienes Nacionales/WikimediaCommons [CC BY 2.0] )

Before modern nation-states were established, the Mapuche defended their lands from two invasions: the Inca Empire around the 15th century and Spanish settlers. The Spanish settlers were ultimately forced to recognize Mapuche self-determination in the 17th-century Quillín Treaty. However, in the late 19th century, Argentina and Chile began invading Mapuche lands to advance their agricultural interests. The Mapuche were split in two by the Argentine and Chilean borders and came under the control of each state. Government discrimination against the Mapuche was not limited to military violence; they were also excluded from political, economic, and social rights. Their resources and land were unilaterally expropriated, and they were expelled from their ancestral territories. They were forced to work on sugarcane plantations and in the military in Argentina’s Tucumán region, and teaching or using Mapudungun in schools was banned. Today, the reason the governments of Argentina and Chile covet Mapuche land is the abundance of natural resources it holds. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, this fertile land is believed to contain the world’s second-largest reserves of shale gas—highly coveted by domestic and foreign real estate, oil, and mining companies. In both countries, the land and rights of the Mapuche are being violated by governments and foreign corporations.

The struggle in Argentina

As noted above, Argentine repression of the Mapuche began in the late 19th century. From 1878 to 1885, the Argentine government carried out a plan ironically named the “Conquest of the Desert”—even though those lands were not desert but fertile and rich. This operation expelled about 15,000 Mapuche from their lands. It was the first government repression of the Mapuche in Patagonia and was conducted with support from Britain, which had been strengthening its economic influence over South American countries by assisting their independence from Spain. Article 75, Section 17 of the Argentine Constitution, established in the 20th century, guarantees Indigenous peoples “communal ownership of traditionally occupied lands.” However, in the 1990s President Carlos Menem began a neoliberal overhaul of the Argentine economy, advancing privatization of government services and assets and encouraging investors and companies worldwide to purchase cheap, fertile lands in Patagonia. Many investors bought land at that time, and Mapuche territories became someone else’s private property, forcing many Mapuche to leave.

In increasingly privatized Argentine lands, the largest private landholder is the global fashion company Benetton, whose holdings span about 890,000 hectares. Uses range widely from livestock and cultivation of raw materials for clothing to exploratory mining, fossil fuel extraction, and logging. Clashes between the Mapuche and the government frequently occur on Benetton-owned land. In January of last year, Argentina’s federal security forces carried out an attack on the Mapuche. Benetton, however, has taken the position that it was “unknowingly involved” and not a party to the incident.

People protesting on Benetton’s private property: Chubut, Argentina (Photo: Prensa Obrera/ Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0])

Argentina is deeply complicit in violating Indigenous rights and ignores established law. Recently, the government has sought to enact legislation that would further infringe on Mapuche rights. The “land-use bill” under discussion in Río Negro Province would allow the provincial government to expropriate Mapuche land for mining, oil, tourism, or real estate. Under this law, the government could control about 2.03 million hectares without regard for the environment or the rights of the Mapuche. Such actions by the government violate the constitution.

Repression in Chile

Chilean repression of the Mapuche began with the Occupation of Araucanía in 1861, a brutal military invasion that ended in 1881 with the Mapuche surrender. Tens of thousands lost their lives, and the Mapuche saw their lands shrink from 10 million hectares to just 500,000. The Chilean government has also ignored Mapuche rights, advancing policies that promote the mining and hydrocarbon industries and oil extraction on Mapuche land. In areas suitable for such extractive activities, government repression has occurred and many Mapuche have been expelled. In response, the Mapuche have engaged in protest actions such as road blockades, destruction of drilling equipment, and demonstrations.

Demonstration march: Angol, Chile (Photo: Carpintero Libre/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

However, the Chilean government has been suppressing these protests through law, namely the Anti-Terrorism Law enacted in 1984 under the military regime. Under this law, witnesses need not reveal their identities, and excessively long sentences and extremely harsh penalties can be imposed. In other words, by treating Mapuche protests against the government as “terrorism,” the authorities can subject the Mapuche to heavier penalties in trials that lack fairness. Mapuche activists who have been indicted and convicted without clear evidence have resorted to hunger strikes. The country’s institutions themselves also cause harm: under Chile’s 1981 Water Code, water-use rights are privatized rather than held by the state. This means water-use rights are priced by the market and freely traded. Because there is no requirement to consider river flow or adequate rules to prevent pollution, serious water scarcity and contamination have become problems. Since water-use rights are left to the market, capital-rich entities such as mining companies can corner supplies, and the right of people living in the region—including the Mapuche—to use safe water is not guaranteed.

Mapuche resistance

In November 2017, Mapuche communities in Argentina and Chile began working together to defend their interests, announcing their first joint cross-border march near the frontier. The aim was to assert Mapuche rights and demand the release of those deemed political prisoners. In December 2017, one month later, Moira Millán, a leader of a Mapuche organization in Chile, and Ingrid Coello Montecino, a leader of a Mapuche organization in Argentina, argued that repression of the Mapuche occurs in daily life and that Chileans and Argentines should unite to defend their rights. They also condemned the fact that both governments harshly punish Mapuche claims in order to serve the interests of foreign companies in Patagonia, and—backed by major media—promote a narrative that government repression is a pretext while portraying the Mapuche as the sole perpetrators of violence. There have been reports of arson attributed to the Mapuche in various places. In August 2017, in southern Chile, 29 logging trucks belonging to a timber company that had clashed with the Mapuche for more than a year over land were burned. Chilean authorities have attributed the arson to the Mapuche and arrested and indicted Mapuche activists, but they deny the charges and have gone on hunger strike to assert their innocence.

Pope Francis visiting Chile (Photo: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Toward an end to the conflict

In June 2017, Chilean President Michelle Bachelet apologized for actions that had repressed Mapuche rights. This was positive as the government’s first apology, but no substantive policies have yet been realized. In January 2018, Pope Francis visited Chile and delivered a speech calling for a peaceful resolution to the conflict between the Mapuche and the government, which may have slightly increased international attention. In March 2018, for the first time, two Mapuche women became members of Chile’s parliament. They were warmly welcomed, and President Sebastián said in his speech that he wanted to put an end to the years of conflict. Slowly but surely, steps toward a peaceful resolution seem to be beginning. We hope that the government’s words of reconciliation and international attention will not be temporary.

Patagonia in autumn: Argentina (Photo: Justin Vidamo/Flickr [CC BY 2.0 ])

Writer: Satoko Tanaka

Graphics: Hinako Hosokawa

地理大好き人間です。あまり知られていない世界の情報をいつもありがとうございます。もっともっと知りたいです。これからも頑張ってください!

侵略された土地では、侵略した側の人の言葉でしか現状が語られないために、先住民にまで思いが至らないのかと思いました。USという国が移民の国ということは、どういうことなのか、帝国主義が大いに勃興した時代に何が起こったのかを、強いものの視点ではなく、弱い立場に置かれた人(が存在しているという認識をすることも含めて)の視点を想像することで、何かわかることがあるかもしれません。

厳しい状況を想像します。2024年11月現在の状況はいかがでしょうか。