When you hear the word “agriculture,” what kind of scene do you imagine? Perhaps a landscape of “lush greenery” spreading under a blue sky over vast land, or “golden, ripened wheat and rice” swaying in the wind sweeping across the fields. Many people likely picture such peaceful, calm scenery. But how many think of the relationship between “agriculture” and environmental destruction or climate change?

In fact, modern agriculture places a heavy burden on the environment. It is a cause of environmental destruction such as the loss of tropical rainforests, desertification, and the disappearance of lakes, and it is also a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Why does agriculture, which nurtures greenery and is nurtured by it, lead to environmental destruction and climate change? Here, we explain the mechanisms and unravel the dilemmas faced by modern agriculture, including livestock and dairy farming.

Cabbage fields bathed in the morning sun (Photo: Artur Synenko / Shutterstock.com)

Factors behind climate change: “Greenhouse gas emissions” from agriculture

Climate change is a threat to humanity. At the 23rd Conference of the Parties (COP23) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, held in November 2017 in Bonn, Germany, with Fiji serving as the presidency, concrete rule-making progressed to implement the Paris Agreement concluded in 2015. The Paris Agreement has been ratified by 173 countries and regions as of now, and the large number of ratifications and the speedy entry-into-force process reflect the sense of urgency toward the “threat” of climate change.

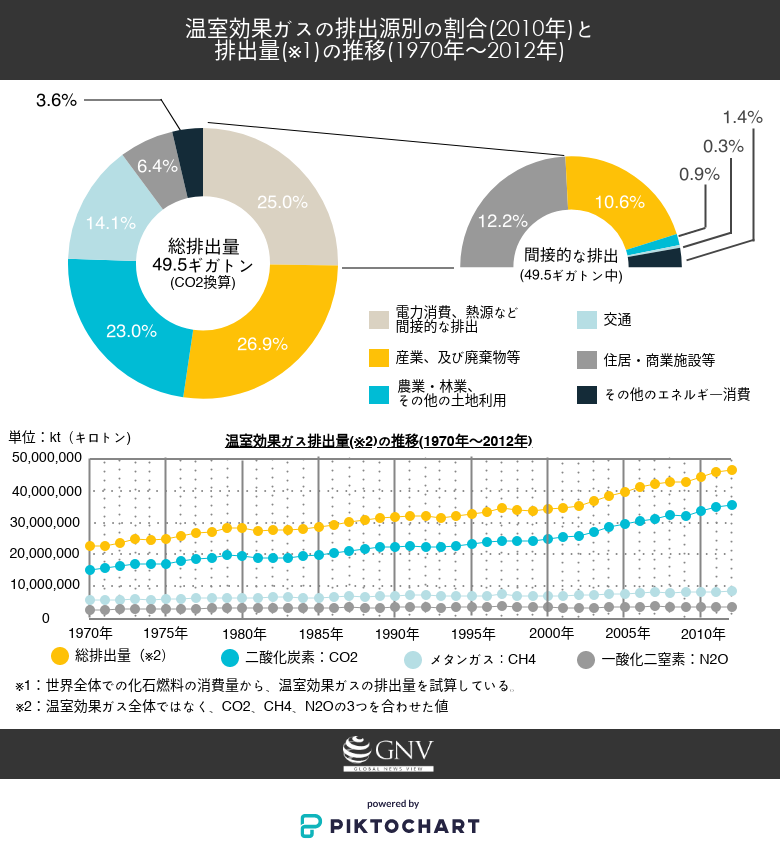

There are data we would like you to look at regarding the causes of this “threat.” According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, 23% of greenhouse gases (Note 1) that drive climate change are emitted by agriculture. Additionally, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 17% of greenhouse gases are agriculture-derived, with an additional 7%–14% from other land use. In 2011, the agricultural sector, including livestock and dairy, emitted more than 530 million tons in CO2 equivalent, an increasing trend from 230 million tons in 1961.

Created based on data from the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (2014) and the World Bank (Carbon dioxide (CO2), Methane (CH4), Nitrous oxide (N2O)).

Why does “agriculture” lead to climate change?

Why does agriculture, including dairy and livestock, account for one-fifth of the factors behind climate change? It is easier to understand if we divide it into two parts: “development to carry out agriculture and dairy/livestock production” and “the activities of agriculture, dairy, and livestock themselves.” We will explain the mechanisms with examples for each.

“Development to carry out agriculture and dairy/livestock production”

From this perspective, deforestation for farmland development is the first link between agriculture and environmental destruction. Mountains are cut down, land is cleared, and farmland and pasture are created. In this process, large areas of forest are felled, contributing to climate change.

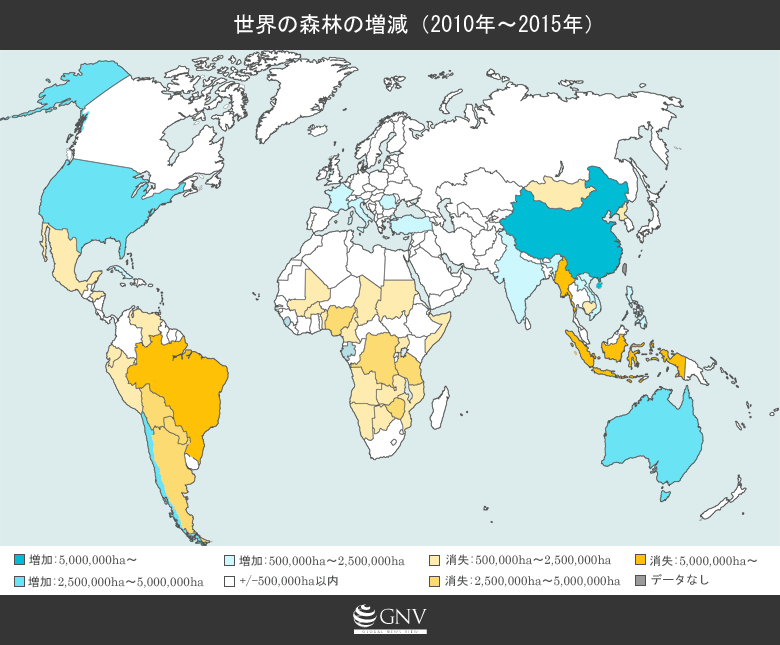

Excessive slash-and-burn is also a major issue. Tropical rainforest regions receive a lot of rain, which washes away surface soil nutrients. Since agriculture uses the topsoil layer, this nutrient deficiency must be addressed. Thus, slash-and-burn is practiced, wherein forests are burned to create sunlit farmland while producing ash containing nitrogen and carbon as nutrients. While this agricultural method is rational in itself, when it is carried out excessively beyond the forest’s regeneration speed, it causes severe environmental destruction. For example, in Indonesia, excessive slash-and-burn for oil palm plantation development and other purposes is conducted in various places and has also caused wildfires that destroy forests.

In the tropical rainforests of the Amazon and Congo River basins, known as the “two lungs of the Earth,” the impacts of such agriculture and other development are striking. The latest satellite surveys show that worldwide, 14 soccer fields (10 ha) per minute—an annual area about 1.8 times that of Hokkaido—of forests are lost due to human activities such as agriculture, logging, and urban development. At this rate, it is calculated that the world’s tropical rainforests will disappear in 100 years.

Created based on FAO data.

Behind such excessive deforestation and land development lies the rapid increase in the world’s population. The global population surpassed 7 billion in 2011 and has now reached 7.6 billion. As the number of people to be supported grows, the production of food—the source of life—must increase. That demand is driving excessive land development.

But that is not the only reason. The continuous rise in meat consumption is another factor that cannot be ignored. Producing meat requires vast quantities of grains such as soybeans and corn as feed, as well as expansive land (pasture) for grazing cattle and pigs. In addition, transporting such feed crops and securing large amounts of water resources are necessary, and (as discussed later) a lot of greenhouse gases are emitted in the production process. “Delicious meat,” produced using enormous land, feed, and resources and with significant greenhouse gas emissions, is in fact a very inefficient food.

Dairy cows eating pasture grass (Photo: Syda Productions / Shutterstock.com)

“The activities of agriculture, dairy, and livestock themselves”

It may be hard to picture, but agricultural production activities themselves can lead to environmental destruction, and greenhouse gases are generated from these processes as well. For example, in mechanized agriculture, fossil fuels are consumed to run machinery at various stages from tilling land to harvesting crops. In forced cultivation using greenhouses, heating or cooling may be necessary day and night, consuming energy. Through such energy consumption, agricultural production emits greenhouse gases.

Furthermore, methane—which has a higher greenhouse effect than CO2—is generated from dairy and livestock industries and rice cultivation. Rice cultivation is a source accounting for about 10% of anthropogenic methane emissions. Oxygen is not easily supplied to flooded paddy soils, and methane-producing microbes that thrive in such environments emit methane. The methane produced is released into the atmosphere through the roots and stems of the rice plants, making recovery difficult. From the dairy and livestock sector, 7.1 gigatons in CO2 equivalent are emitted annually—14.5% of greenhouse gases from human activities. Of this, 44% is emitted as methane, with specific sources including livestock respiration and belching, and energy consumption for heating and cooling—making it one of the major climate change factors.

FAO data used as the basis.

Other factors include overgrazing—such as by goats that eat grass down to the roots—which rapidly strips the land of greenery. In arid regions, ill-suited irrigation agriculture consumes scarce soil nutrients the more it is practiced, accelerating land degradation. Furthermore, excessive use of irrigation water draws minerals from deeper soil layers up to the surface through capillary action, depositing salts on the surface (salinization). Land affected by salinization becomes barren and loses greenery. As land degradation progresses in this way, topsoil is eroded by wind and rain, and the “cycle of organic matter (carbon-containing compounds)”, which plays a role in fixing CO2 in the soil, ceases to function. As a result, greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere.

The “dilemma” faced by modern agriculture

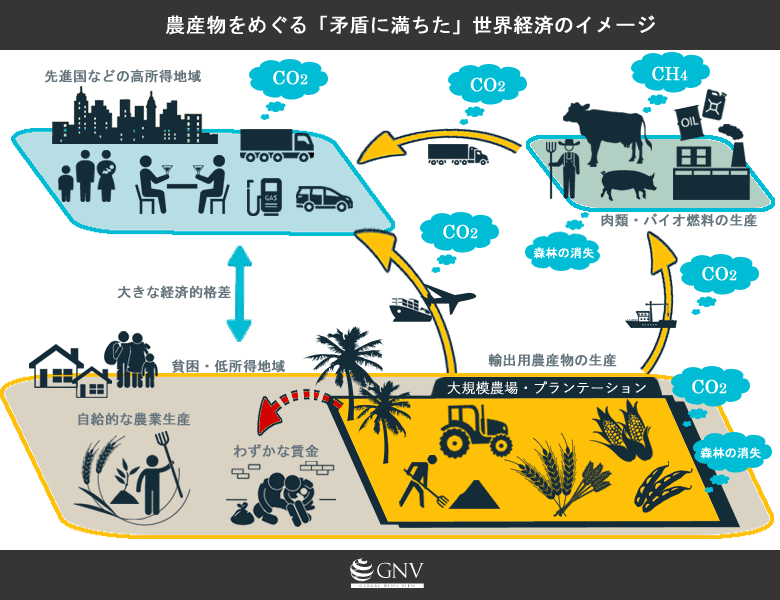

As shown, the more modern agriculture develops and produces, the more it generates the causes of climate change and extreme weather, leading to a crisis for agriculture itself—a dilemma. Moreover, the economic system in which modern agriculture is embedded is rife with contradictions not only in terms of climate change, but also regarding the correction of poverty and inequality.

Agricultural machinery working on vast farmland (Photo: Holnsteiner /Pixabay)

The number of undernourished people worldwide without access to “food” reaches 815 million (about 11% of the world’s population). Meanwhile, large quantities of crops produced by large-scale mechanized farming are often grown as export cash crops; such crops are transported outside their production areas using energy from fossil fuels and consumed for meat and biofuel production.

In other words, by using energy to transport food produced (in many cases) by low-income people for meager wages and using it for meat and fuel production, we both magnify the threat of climate change—pushing food production itself to the brink—and force the producers into poverty and hunger, all so a portion of humanity can enjoy a rich diet. Perhaps sustainable agricultural production for both the planet and humanity is not today’s mass production via large-scale mechanization, but rather a self-sufficient, local mode of production.

Meanwhile, at the level of each of us, we at least need to change how we procure food and how we think about it. Where did the ingredients before us come from? How much crops, water, fertilizer, and fuel are used to produce those ingredients? And how is it that foods supposedly produced in distant places can be obtained at that price? Imagining the “backstory” of each food item lined up in the supermarket might be quite an interesting exercise.

In exchange for “the prosperity of this very moment,” we continue to leave our children to foot the bill in various forms—from climate change to the structure of inequality.

[Footnote]

Note 1: There are several types of “greenhouse gases.” Well-known carbon dioxide (CO2) is, strictly speaking, one of the greenhouse gases, and methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) are also known as greenhouse gases, and are closely related to agriculture.

Writer: Yosuke Tomino

Graphics: Yosuke Tomino

0 Comments