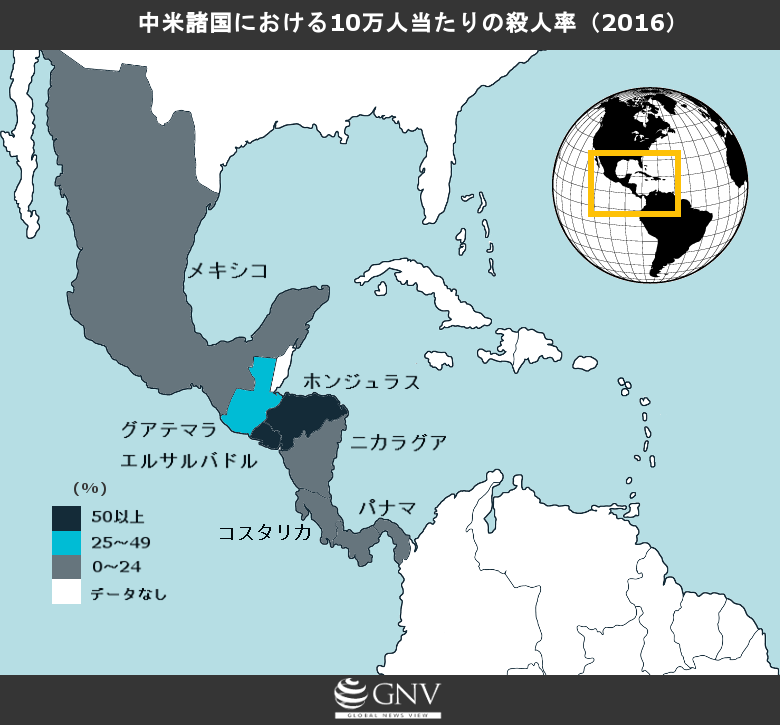

Situations in which people are forced to suffer violence and poverty are not limited to war zones. In the Northern Triangle of Central America, it is said that as many as three homicides occur per day. According to Insight Crime, in 2016, per 100,000 people, 81.2 in El Salvador, 59.3 in Honduras, and 27.3 in Guatemala were killed.

Created based on data from Insight Crime

It is also estimated that about 60% of the people living in this region are in poverty. In 2016, nominal GDP per capita was US$4,227 in El Salvador, US$4,070 in Guatemala, and US$2,609 in Honduras—about one-tenth of the OECD member average ($38,883). According to the World Bank, the share of people living at the absolute poverty line of US$1.90 a day or less is 3.0% in El Salvador, 9.3% in Guatemala, and 16% in Honduras, indicating high levels of severe poverty. Why has the Northern Triangle of Central America become a hotbed of violence and poverty? Let’s look at the circumstances people in the Northern Triangle have faced historically and are facing now.

Colonialism and a monoculture economy

El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras became Spanish colonies from the 16th century, when Columbus reached the Americas. Prior to colonization, the Maya civilization and the Aztec Empire had flourished, but with the Spanish invasion, much of the region’s wealth, including valuable resources, was extracted. Subsequently, the area comprising the present-day three countries plus Nicaragua and Costa Rica became the Captaincy General of Guatemala. In the first half of the 19th century, the Captaincy General gained independence from Spain but was soon brought under the Mexican Empire. Less than a year later, the Mexican Empire collapsed, and the region became the Federal Republic of Central America. However, due to conflict between conservatives and liberals, the federation also collapsed in about 15 years, and El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras separated into independent states.

One cause of the poverty that continues to this day was the large-scale plantations established by U.S. corporations beginning in the late 19th century. Because the humid, fertile soil was ideal for agriculture, large U.S. plantations were set up across the three countries. As a result, their economies became monocultures centered on bananas and coffee. To export cheaply to developed countries, they had to keep producing only what those countries demanded, and people lost their self-sufficiency. As self-sufficiency declined, farmland that had produced staple foods was replaced by banana and coffee plantations, contributing to hunger. Plantations did create jobs, but people had to work long hours for extremely low wages in harsh conditions. Because so many people had to work on plantations, other industries such as manufacturing did not develop. There was also a political dimension in which the plantation-operating companies, in coordination with the U.S. government, interfered in the three countries’ politics. In return for support to maintain dictatorships, laws favorable to plantation operations were enacted—creating the so-called “banana republic” situation.

Day laborers on a plantation near the El Salvador–Guatemala border IM Swedish Development Partner/Flickr[CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Anti-government wars intensified by the Cold War

Wealth and power were concentrated in the hands of landlords and other economic elites, and among the people, resistance to class-based and ethnonational disparities was growing. Influenced by the successful 1959 Cuban Revolution that established a socialist state in the neighboring country, anti-government wars began in Guatemala in 1960 and in El Salvador in 1972. At that time, the world was in a Cold War between the Soviet Union, which espoused socialism, and the United States, which espoused capitalism. Both competed to bring countries into their respective camps, and they intervened in the wars in El Salvador and Guatemala through military and material support. The support of the two superpowers prolonged the wars, causing many casualties and displacing many people. Although there was no war in Honduras itself, during the conflicts in neighboring Guatemala and in Nicaragua, the United States established major anti-communist military bases there, and many civilians were conscripted to fight as soldiers.

These wars turned many people into refugees who fled from the Northern Triangle to the United States. With the end of the Cold War in the late 20th century, the wars in El Salvador and Guatemala ended. Despite the fact that support from the United States and the Soviet Union had intensified the wars, after the peace accords both powers withdrew from the region, leaving behind devastated towns. The three countries were left awash in weapons used in the wars and in unemployed people whose role as soldiers had ended. Without support from the great powers, the countries lacked the ability to rebuild. In regions where government control is weak and poverty is widespread, and where unemployed people can easily obtain weapons, conditions were set for the gangs and transnational criminal organizations described below to gain power in these three countries.

Challenges left after the Cold War

Even after Cold War interventions ended, political and economic power remained concentrated among landlords and government-affiliated figures who had ties to the great powers during the Cold War. Democracy has not functioned, and corruption is rampant. The countries are unable to adequately respond to domestic crime and violence, nor to implement economic policies that provide citizens with formal employment. About 95% of homicides in the three countries go unprosecuted and are buried in obscurity. Government agencies are riddled with corruption. Not a few customs officials are complicit in drug smuggling. Some police officers who should protect citizens instead threaten them and extort money.

Demonstration protesting political corruption Honduras rbreve/Flickr [CC-BY-NC 2.0]

The region also faces external threats from the international drug trade. With politics not functioning properly, the three countries are very convenient locations for transnational criminal organizations. Two main actors plague the people of the Northern Triangle: transnational criminal organizations that operate across borders and locally based gangs.

Two evils (1): Transnational criminal organizations

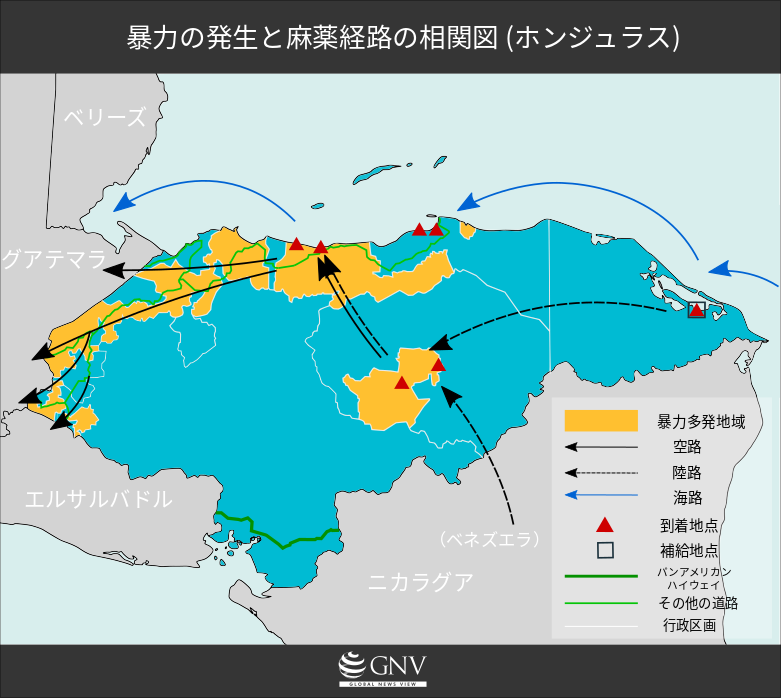

The Northern Triangle has become a drug-smuggling corridor for Mexico-based transnational criminal organizations (such as the Zetas). Cocaine produced in Colombia is smuggled through the Northern Triangle to the United States, the main consumer. In areas where these organizations operate, residents’ homes are used as warehouses to store cocaine. Many residents have had their homes confiscated and have been forced to relocate. Young people in villages are coerced to join the organizations. Homicide rates are higher along smuggling routes. This is clear from the figure below showing drug routes and the incidence of violence in Honduras. Along the smuggling routes, transnational criminal organizations exercise territorial control and politics does not function. Many residents face danger on a daily basis.

Created based on data from Duke University

Two evils (2): The presence of the Maras

Another force that torments people in this region are locally based gangs known as Maras. Maras mainly finance their activities by extorting people and taking their money. According to the Honduran National Anti-Extortion Force, the estimated annual losses due to extortion are US$390 million in El Salvador, US$200 million in Honduras, and US$61 million in Guatemala. Such vast sums have been flowing to the gangs. Money obtained through extortion is also used to bribe police officers and judges, and to hire lawyers. Children and young people are coerced to join the groups, and young women are subjected to heinous sexual violence, forcing many people to relocate. Recently in Honduras, gun battles between these two groups have taken place at elementary schools attended by children. Children cannot attend school safely.

Various groups exist depending on the area, and many civilians are caught up in this turf war. The two groups with significant power in the Northern Triangle are MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and M-18 (the Eighteenth Street Gang). The power struggle between MS-13 and M-18 is intense. As part of that struggle, they sometimes compete over how many people they kill, and many lives are lost.

Public disarmament event El Salvador (Departamento de Seguridad Publica OEA / Arena Orte /Flickr [CC-BY-ND 2.0])

The governments have also begun initiatives to address the gangs, and the three countries—El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—have announced that they will cooperate to confront them. There have been successes. In 2012 in El Salvador, government intervention led to an 18-month truce between gangs, during which the homicide rate fell by more than 40%. In addition, although not many, more programs are emerging by companies and others to support the social reintegration of former gang members and to help young people suffering from poverty find jobs so that they do not join gangs.

In the Northern Triangle of Central America, violence and poverty create a vicious cycle. For people to live in safety, both violence and poverty must be broken. In recent years, initiatives by governments, human rights groups, and international organizations such as the United Nations have begun. There may not be many things ordinary citizens can do directly, but one action people can take in their daily lives is fair trade. Purchasing the main products of the three countries at fair prices will help promote their economic growth. We hope the day is not far off when people in the Northern Triangle of Central America can live in safety.

Cityscape El Salvador Milosz Maslanka/Shutterstock.com

Writer: Satoko Tanaka

Graphics: Hinako Hosokawa/Miho Horinouchi

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks