Up to now, GNV has analyzed international news coverage in Japan in News View and identified its trends. In the article analyzing international reporting in Japan in 2015, it became clear that the amount of international reporting in Japan is low compared with other genres and other countries, and that there is a reporting bias whereby countries with close ties to Japan are covered more while there is little reporting on poorer countries. How might these tendencies change amid an increasingly globalized world in which people, money, goods, and information flow actively? This time, we analyzed international reporting in Japan in 2016 to examine its trends.

Share of international reporting (2016)

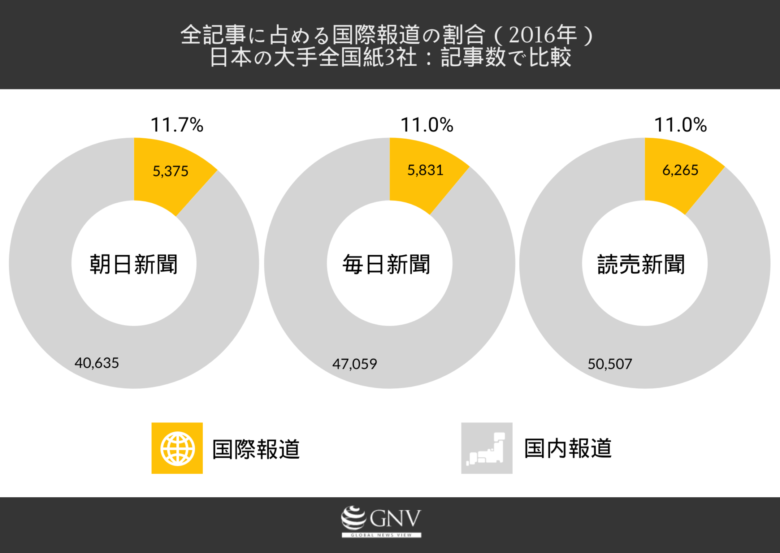

First, let’s look at the share of international reporting in 2016. The figure below shows, for Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun, the percentage of international news articles out of all articles (Note 1).

The results were Asahi: 11.7%, Mainichi: 11.0%, Yomiuri: 11.0%, with all three papers showing almost the same share of international reporting. Compared with the 2015 figures (Asahi: 10.0%, Mainichi: 9.3%, Yomiuri: 8.9%), this represents a slight increase. In fact, in 2016 all three papers increased not only the share but also the absolute number of international news articles compared with 2015. This increase is important because it helps deepen our understanding of the world. Now, let’s compare these numbers with others. For example, take sports articles, one form of entertainment (also discussed in a previous article). In 2016, the share of sports articles was Asahi: 24.1%, Mainichi: 23.7%, and Yomiuri: 19.5%—roughly double the share of international news and amounting to about one-fifth to one-quarter of all articles. The share of sports articles is also almost the same as the 2015 figures. This gives a sense of how small the share of international reporting actually is.

International reporting volume by region (2016)

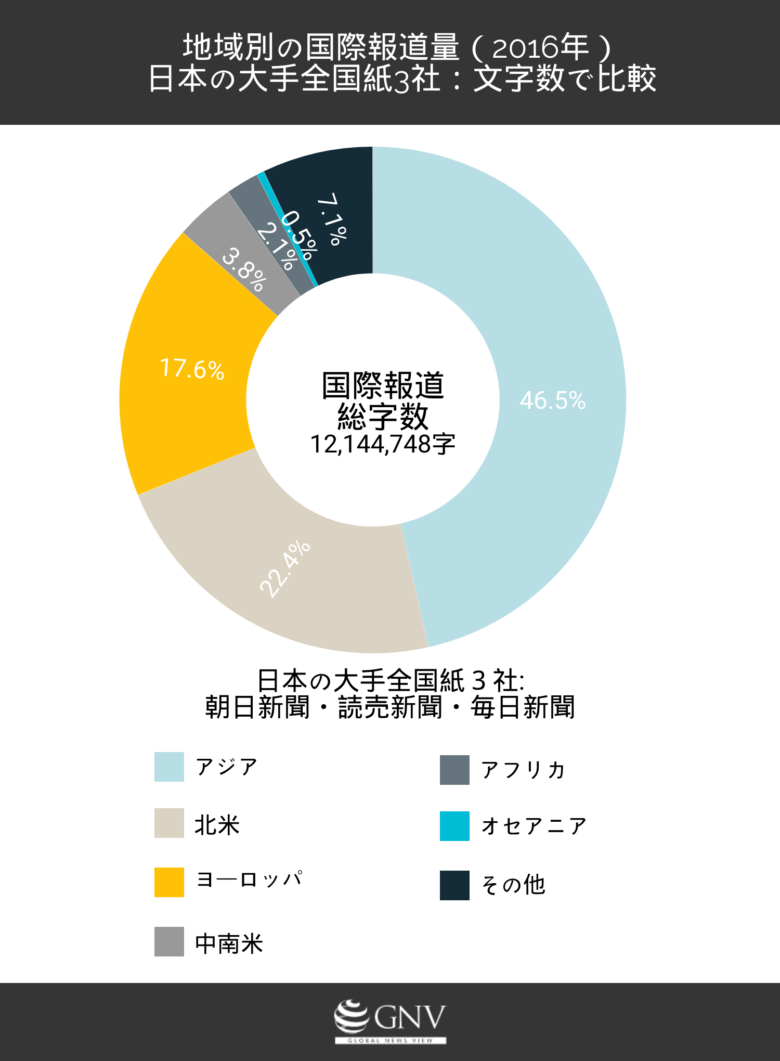

Next, let’s look at the volume of international reporting by world region (Note 2). Here we add together the volume (character counts) of international reporting by Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri in 2016 and examine the percentage by region (Note 3). The figure below shows the results.

In descending order, the shares were Asia, North America, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Oceania, with Asia accounting for a dominant 46.5%. Next came the advanced regions of North America and Europe. Remarkably, Asia, North America, and Europe alone accounted for 86.5% of all international reporting. In contrast, the combined total for Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Oceania was a mere 6.4% (unchanged from 2015 at 6.4%). Looking at the 2015 figures, the order was Asia: 47.9%, Europe: 23.7%, North America: 14.0%, Africa: 3.4%, Latin America and the Caribbean: 2.1%, and Oceania: 0.9%, indicating differences between 2016 and 2015 in the regional distribution of coverage. Comparing 2016 with 2015, North America’s share increased substantially while Europe’s declined markedly, swapping places. The same can be said for Latin America and the Caribbean versus Africa. Looking more closely at character counts, North America increased by 1.8 times and Latin America and the Caribbean doubled. By contrast, Europe decreased by about 20%, Africa by about 30%, and Oceania by about 45%. Although Asia’s share declined slightly, in terms of characters, coverage of Asia actually increased by about 10% from 2015.

In 2016, the volume of reporting on Asia, North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean increased, while other regions saw declines. Looking at the data by country reveals the increases and decreases relative to 2015 in greater detail. Let’s examine the country-level figures.

Top 10 countries by reporting volume (2016)

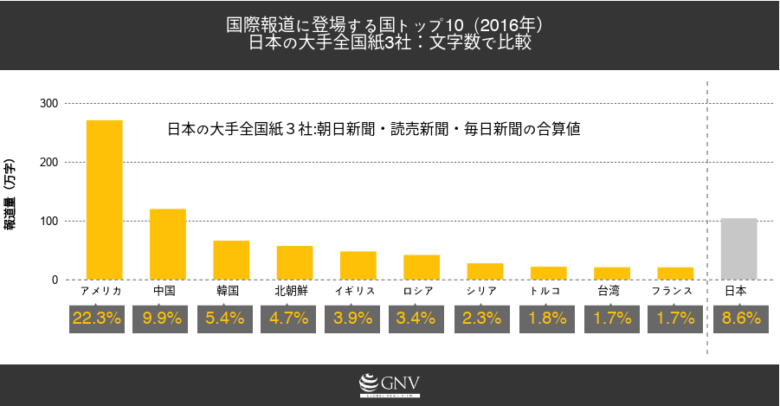

The figure below shows the top 10 countries by volume of international reporting in 2016. The numbers on the far right indicate the amount of coverage, within international reporting, that was related to Japan.

It is clear that coverage of the United States was exceptionally abundant. Compared with 2015, reporting on the U.S. increased by about 1.16 million characters—nearly doubling the 2015 total. Following the U.S. were East Asian countries: China, South Korea, and North Korea. The United Kingdom, which ranked 10th in 2015, rose to 5th. Seven of the top 10 countries—excluding North Korea, Turkey, and Taiwan—also made the top 10 in 2015.

What events drew attention in 2016? In the United States, the tumultuous presidential election attracted immense interest. Remarkably, for U.S.-related coverage alone, articles in Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri whose headlines included the term “presidential election” totaled about 800,000 characters, accounting for about 30% of all U.S.-related reporting and roughly 70% of the increase from 2015. Elsewhere, in the United Kingdom, the referendum decision to leave the EU sparked major debate. North Korea announced its first hydrogen bomb test and launched numerous ballistic missiles, drawing international condemnation and attention to countries’ stances toward North Korea, such as strengthened sanctions. In Turkey, terrorist attacks and a large-scale attempted military coup became focal points and were extensively covered. In Taiwan, a presidential election brought the Democratic Progressive Party’s Tsai Ing-wen to office; the change of administration and the first woman president drew significant attention.

As you can see, the top 10 consists of advanced Western countries, East Asian countries geographically close to Japan, and countries in the Middle East where brutal conflicts among various forces continue. These 10 countries alone account for about 60% of total coverage. In contrast, no countries from Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, or Oceania appear in the top 10. These patterns are almost identical to those in 2015.

So how much coverage did countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Oceania receive? The most-covered country among these regions was Brazil, host of the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, ranking 11th overall by volume. Coverage of Brazil was about 4.6 times that of 2015, and Brazil alone accounted for about 40% of all reporting on Latin America and the Caribbean. Articles in Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri whose headlines included the term “Olympics” accounted for about 40% of Brazil-related coverage (by characters). In Africa, South Sudan—where Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force was participating in UN peacekeeping operations (PKO)—received the most coverage, accounting for about 25% of reporting on Africa. However, the bulk of this was coverage related to the GSDF’s PKO rather than about South Sudan itself. In Oceania, coverage of Australia overwhelmingly dominated, accounting for about 70% of the region’s reporting; in 2016, a double dissolution election for both houses was held, drawing attention. As this shows, these regions already receive little coverage, and yet a single high-profile country accounts for the overwhelming majority of reporting from each region. Although dozens of countries exist in each region, many receive almost no coverage. Given the scarcity of information on these regions in international reporting, are we truly deepening our understanding of them?

Concluding remarks

The trends in international reporting in 2016 were broadly the same as in 2015. Although the volume increased slightly, most of the increase was taken up by U.S.-related coverage tied to the presidential election. The facts remain unchanged: international coverage is still limited in quantity, and the countries and regions covered are heavily skewed. It is understandable to feature countries closely connected to Japan and to focus on events that warrant attention. However, when the overall amount of international reporting is small and the distribution by country or region is already highly uneven, devoting even more coverage to a single event causes the balance to collapse. In 2016, elections and the Olympics provided ideal news hooks and amplified this trend. When the volume is low and the coverage highly biased, there is a risk that audiences’ conception of the “world” becomes very narrow and skewed. Needless to say, in an increasingly globalized era, understanding the world is essential, and our current, bias-laden understanding based on such information can hardly be called true understanding. Will the trends in international reporting in Japan remain unchanged going forward? This analysis has only heightened our sense of urgency. We will continue to analyze coverage and hope to see international reporting in Japan change to reflect the world objectively and comprehensively.

Note 1: We consulted each company’s online database. For the definition of international news articles, see “GNV Data Analysis Method [PDF].”

Note 2: Regions are divided into six—Asia, Africa, Oceania, Europe, North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean—following the standards of the UNSD (United Nations Statistics Division).

Note 3: Character counts are based on GNV’s own criteria.

Writer: Taihei Toda

Graphics: Taihei Toda

0 Comments