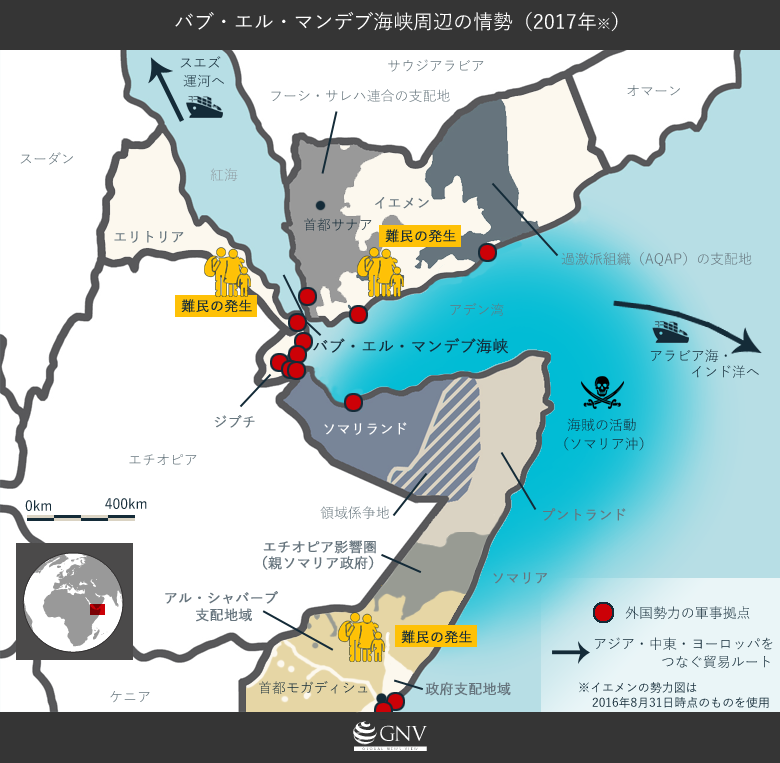

Located in the southern Red Sea, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait is the strait near the borders of Yemen in the southwestern Arabian Peninsula and Eritrea and Djibouti in East Africa (Map here). Because the strait is narrow—about 30 km wide—has rapid currents, and, moreover, strong seasonal winds blow from the Indian Ocean toward the Mediterranean for several months each year from November, ships sailing from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean found passage through the strait extremely difficult; it is said sailors came to call it the “Gate of Tears (Gate of Grief).” Today, however, people living near the strait are shedding tears for reasons different from the name’s origin. The countries surrounding the strait are entangled in a complex mix of governance issues, conflict and security problems, and refugee issues.

EU warship at the port of Djibouti Vladimir Melnik/shutterstock.com

Carrying oil and all kinds of goods, this strait is a highly important sea route linking Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated that in fiscal year 2014 an average of 4.7 million barrels per day of crude oil and petroleum products passed through the strait. The fastest route connecting Europe and Asia is the Bab el-Mandeb–Suez Canal route. Because of its narrowness, traffic through the Bab el-Mandeb can be disrupted by conflicts in neighboring countries. Instability in these waters affects the safety of global maritime trade routes and maritime communications and could pose a serious threat to international business. The situation here is hardly irrelevant to people’s lives around the world. So what problems are occurring in the neighboring countries? Let’s take a look.

Eritrea like North Korea

Eritrea is now called the North Korea of Africa. Since independence from Ethiopia, 25 years of dictatorship have made Eritrea one of the world’s most repressive states. Since achieving de facto autonomy in 1991, President Isaias Afwerki has continued to rule without elections and without institutional checks. Since 2002, Eritrea has had no legislature, and the judiciary is under executive control and interference. The constitution adopted in 1997 has still not been implemented, and domestic nongovernmental organizations are not recognized at all. In these circumstances, citizens are subjected to conscription and forced labor. Although the law sets conscription at 18 months from age 18, in practice it is indefinite, and those who attempt to flee face severe punishment.

March demanding democratization in Eritrea (United States) Steve Rhodes/flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Freedom of speech, expression, and religion (only certain denominations are recognized) is also suppressed. Since 2001, there have been no media outlets other than those under government control. In the Press Freedom ranking, Eritrea ranked worst in the world for ten years until 2017, when it was overtaken by North Korea. All of the limited number of newspapers, radio, and broadcast outlets are state-run. In 2016, a UN Commission of Inquiry issued recommendations to the government regarding human rights violations, but no improvements have been seen. Eritrea is isolated, criticized by many countries for the prevalence of human rights abuses, and although a peace agreement ended the war with Ethiopia that claimed over 100,000 lives, the two countries remain deeply at odds because no agreement has been reached on the border demarcation.

A divided Yemen

In Yemen, northeast of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, a fierce conflict is underway, and control of the country is divided among: anti-government forces—an alliance between former president Saleh, backed by Iran, and the Shiite armed group the Houthis—who hold the northwest including the capital Sanaa; the interim government of President Hadi, supported by a Saudi-led coalition and backed by the United States and the United Kingdom; and the extremist group al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). At present the three sides remain locked in a three-way struggle. For details, please refer to this article, but even into 2017 the humanitarian crisis in Yemen has remained severe. Deaths due to the conflict are said to have exceeded 10,000 since 2015, and the International Committee of the Red Cross warns that cholera infections in the country could reach one million by 2018. One million would be the largest number recorded in the world since World War II.

Displaced persons camp in Yemen European Commission DG ECHO/flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Somalia without a government, unrecognized Somaliland

Since 2012, Somalia has established a provisional new government with international backing, but fighting by the al-Qaeda–linked al-Shabaab armed group continues, and the government is barely able to govern the capital and parts of the country. Al-Shabaab carries out targeted attacks on civilians and civilian facilities, waging intense assaults such as suicide bombings and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). More than 1.5 million Somalis are displaced and struggle to access food aid and medical care, which are severely restricted. There are also reports of indiscriminate mass forced evictions by the interim government in the name of clearing al-Shabaab, and of abuse against women and children.

Since declaring independence in northern Somalia when the conflict broke out in 1991, Somaliland has remained stable compared to other regions. Democratization has progressed, establishing political institutions such as local and general elections under a multi-party system, government agencies, police, and its own currency. However, the international community, including the African Union, does not formally recognize Somaliland as a state, and it continues to seek international recognition. Puntland, located between Somaliland and Somalia, is likewise not a state. While it does not seek formal independence, it currently functions as a de facto autonomous region. The boundary between Puntland and Somaliland is also disputed.

Conflicts and security issues linking the region

As noted, Eritrea, Yemen, and Somalia each face a variety of domestic problems, and their internal instability spills over their borders to affect neighboring countries. It also extends across the broader region, involving actors such as the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. The Saudi-led coalition has imposed a naval blockade around Yemen’s waters, controlling entry and exit, including humanitarian aid. The Yemeni conflict has drawn in Eritrea, a previously closed-off state. Eritrea pledged contributions to the Saudi and Gulf allies, allowing them to use Assab port and airspace to participate in the fighting; in return, Eritrea is reportedly receiving money and fuel. Eritrea’s support also includes more than 400 Eritrean soldiers joining expeditionary forces to counter the Houthi rebels. Furthermore, the Eritrea–Ethiopia rivalry has played out in the Somalia conflict as well. Eritrea has historically provided military support to al-Shabaab forces opposing Ethiopia’s intervention in Somalia.

There is also a piracy problem off the coast of Somalia. Although it has calmed somewhat, it remains a threat. Somalia—particularly Puntland—has served as a base for pirates. To protect crucial cargo routes, countries such as the United States, Italy, France, China, and Japan have established military bases in Djibouti between Eritrea and Somaliland, showing their presence in these waters and monitoring developments there.

Parent and child and soldier in a settlement of internally displaced persons in Somalia IRIN Photos/flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Refugee issues

The Yemeni conflict is increasing the number of refugees from Yemen, and refugees from Somalia and Eritrea are also left with nowhere to go. In Eritrea, about 12% of the population flees abroad as refugees or asylum seekers. Yemen has traditionally been generous in accepting those in need of international protection and is the only country on the Arabian Peninsula to have signed the Refugee Convention and its Protocol, but the ongoing conflict has completely stripped it of the ability to provide sufficient assistance and protection to refugees. While some Somali refugees residing in Yemen are choosing to return to Somalia in the midst of Yemen’s conflict, there has also been an incident in which a Saudi helicopter opened fire on a boat carrying Somali refugees attempting to enter Yemen, killing 42 people. Now that Yemen can no longer accept refugees, which country will?

Somali coast with people lining up to board boats to Yemen (2007) Photo Unit/flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0]

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), Djibouti has accepted about 4,000 people from Yemen. Djibouti is a very small country already hosting many refugees and internally displaced persons, and its humanitarian resources are at their limit. Refugees from Yemen are also moving to Somaliland and Puntland. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the numbers are still very small, but there is movement of people fleeing from Yemen to Somalia. Somaliland’s foreign minister Mohamed Yonis says the region is preparing to accept up to 2,000 Yemeni refugees. However, Djibouti is already hosting tens of thousands of refugees from Somalia and elsewhere; about 24,000 refugees live in Djibouti and about 9,000 in Somaliland. UNHCR’s 2016 report counts 270,000 refugees in Yemen, 10,000 in Somalia, and 2,300 in Eritrea. The number of internally displaced persons is much higher—two million in Yemen and 1.5 million in Somalia. As noted above, those who cannot leave their countries face dire humanitarian conditions. Whether they remain inside their countries or flee abroad, they continue moving in search of a way out of their circumstances.

Thus, the countries surrounding the Bab el-Mandeb Strait are caught in highly complex circumstances. Conflicts do not remain confined within borders. They draw in neighboring countries and, at strategically important points like the Bab el-Mandeb, can escalate into situations that involve the entire world. When will such complex, ever-expanding problems be resolved? When will the tears of those grieving at home and abroad finally stop?

U.S. aircraft carrier transiting the Bab el-Mandeb Strait U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/U.S. Fifth Fleet/flickr [CC BY 2.0]

Writer: Miho Takenaka

Graphics: Yosuke Tomino

0 Comments