On April 24, 2013, a commercial building collapsed in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, in an incident that claimed the lives of 1,134 workers who were working inside. The building also housed subcontracted factories of globally renowned apparel companies. The incident was widely reported around the world, and through coverage and investigations it emerged that cracks had been found in the building the day before the accident and the local police had warned the building’s owner to stop using it, but the owner ignored the warning and continued to operate the factories, leading to the disaster. It was also revealed that the building had originally been constructed for commercial use, not designed for factory operations, and that the 5th to 8th floors had been added illegally. The Rana Plaza incident highlighted labor issues such as poor working environments and the use of cheap labor through which globally famous companies were making profits; because it was widely reported, attention temporarily focused on labor problems in the fashion industry.

Rana Plaza collapse.By rijans [CC-BY-SA-2.0]

目次

What are the labor issues in the fashion industry?

So what kinds of labor issues exist in the apparel industry? Broadly speaking, two are often cited. The first is the working environment. In particular, this includes child labor, issues of health and safety, and forced labor. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates there are 168 million child laborers worldwide. The apparel industry, in particular, has many jobs that require no special skills, and many of these are more suited to children than to adults, so child labor is prevalent. Although each country has laws regulating the labor and working hours of children under 18, these are often ignored. Many child laborers work for low wages and in poor conditions to support their households. The apparel industry often pays more than other jobs, but children are not only made to do dangerous, substandard work; their basic right to education is also violated. There are also health and safety problems. In the various stages of making clothing, workers may be exposed for long periods to pesticides and lead-based dyes, or suffer poisoning from chemicals, leading to illness or, in the worst cases, death. According to a study by IIS University on garment factories, for example, in the cutting process 35% of workers reported musculoskeletal disorders and 20% had convulsions or respiratory problems. In the sewing process, 55% of workers had musculoskeletal issues and 40% had neurological problems such as headaches.

In addition, there are problems of forced labor. According to the World Encyclopedia, forced labor is the compulsion to provide labor against one’s free will after depriving mental and physical freedom through the use of coercion or threats; this can mean being unable to take time off, or being made to work long hours without breaks other than lunch. There are real cases where people are forced to work from morning until 10 or 11 at night. Shortly before the Rana Plaza accident, a fire broke out at the Tazreen Fashions garment factory in the Ashulia area on the outskirts of Dhaka, killing 112 people and injuring more than 200. At the time, doors had reportedly been locked from the outside to keep workers from leaving, preventing them from escaping the fire. In this way, there are cases where freedom of movement is forcibly taken away and long hours are imposed.

Clothing factory in Dhaka.By Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0]

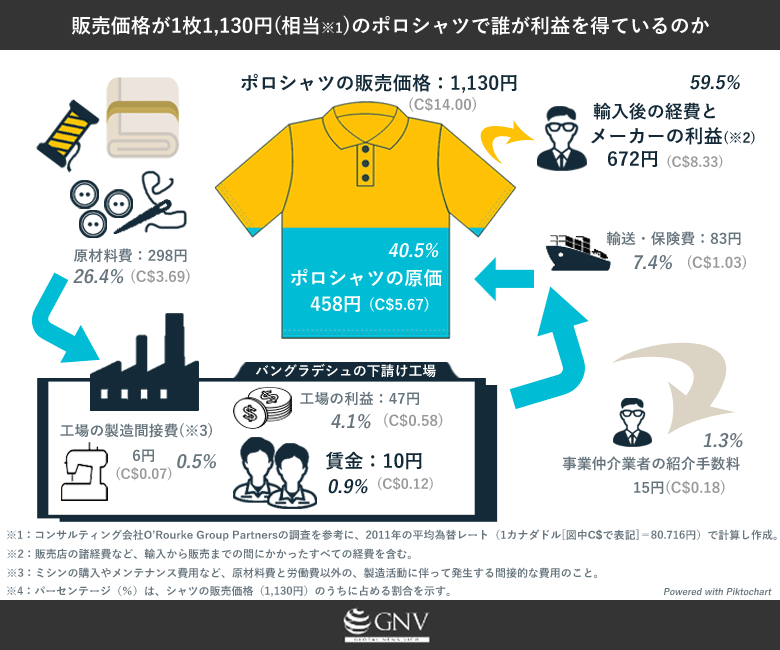

The other major issue is working conditions, particularly low wages. In Bangladesh, the minimum wage for manufacturing workers is equivalent to 12,718 yen per month (calculated at 1 dollar = 103.396 yen), one-fifth that of China and one-third that of India, the lowest in Asia, making it an ideal country for brands seeking to cut costs. So how much are costs such as labor actually being reduced? A 2011 study by a consulting firm examined how much money is paid to whom for a 1,130-yen polo shirt.

According to this study, the cost of a 1,130-yen polo shirt is 458 yen, of which only 10 yen is paid to workers—just over one-fifth of the factory’s profit of 47 yen. From the consumer’s purchase price, the wages workers receive at the factory amount to only 0.9%. This shows how workers are exploited and how brands are profiting.

Why aren’t labor issues improving?

Behind the problems described above are brands’ profit-first mentality and the fast fashion boom. Fast fashion refers to fashion brands and business models that incorporate the latest trends while keeping prices low, and that mass-produce and sell globally in short cycles. Because products must constantly change to keep up with trends, speed is essential. In such a market, there is a massive demand for people who will work long hours for low pay.

Demonstration by garment factory workers.By Sifat Sharmin AmitaCC BY-ND 2.0.

Before the 1980s, many apparel factories were in China, and one often saw the words “Made in China.” From the 1990s, production bases were gradually shifted to Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia and Myanmar, and from around 2000 to the present, Bangladesh has become the world’s second largest in garment export value. This shift is driven by the costs associated with clothing. In other words, in order to reduce manufacturing costs, companies move their production bases to countries with cheap and abundant labor.

Because companies go to countries with an abundance of low-wage workers, supply exceeds demand, and even with poor working conditions such as low pay and long hours, workers have no choice but to accept them. Children are sometimes used as cheap labor as well.

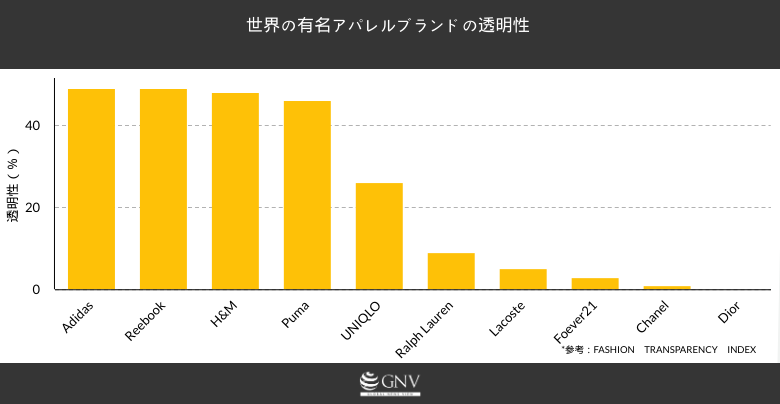

From this corporate mindset, there are two specific reasons labor problems are not moving toward resolution. The first is a lack of transparency and low traceability due to outsourcing everything to subcontractors. There are many processes involved in making clothes. Not all of these processes are handled directly by the brands: there are companies that make the fabric used to make clothing, companies that spin the yarn to make that fabric, and companies that produce the raw materials for that yarn—in other words, brands have relationships with many subcontractors and subcontractors of subcontractors. These relationships are complex, and reaching the very end of the chain requires tracing through many intermediaries. Therefore, it can be costly and difficult for brands to grasp all their subcontractors, and in some cases subcontractors are kept undisclosed to hide child labor or poor working conditions. According to a ranking of transparency in the manufacturing processes of 100 major global apparel brands, the transparency of brands such as Adidas, Reebok, H&M, and Puma is in the 40% range; these numbers are on the higher side, with only 8 out of 100 brands above 40% and none above 50%. UNIQLO is in the 20% range; Ralph Lauren, Chanel, Forever21, and Lacoste are around 10%; and Dior is at 0%. Thus many companies lack transparency, can evade responsibility by claiming subcontractors acted on their own, and because there is no information on factories, governments also find it difficult to create effective penalties for poor working environments, human rights violations, and child labor.

The second is that, not only in Bangladesh but in many developing countries, employers obstruct the formation of labor unions. Because unions are underdeveloped and weak, even with low wages and poor working conditions, workers cannot unite to confront employers, leaving brands to have their way.

What initiatives are being taken?

So what measures are currently being taken to address these labor issues? One is overseas efforts. There is the Clean Clothes Campaign, an alliance of labor unions in the garment industry in 12 European countries and NGOs, which informs companies and citizens about the realities of the clothing industry in order to improve working conditions in developing countries. The campaign conducts online petition drives and, every year during the week of April 24, the date of the Rana Plaza incident, spreads on social media such as Twitter and Instagram during Fashion Revolution Week using the hashtag #whomademyclothes. To date, this hashtag has generated about 70,000 posts and reached 129 million people. In this way, activities from the consumer side have focused not only on price and quality but also on the processes by which clothing is made.

Another is a domestic effort. A research team at BRT University in Bangladesh undertook an initiative to list and map all factories in Bangladesh, including detailed information. This made it possible to see at a glance what is happening where.

Lastly, there are moves by brands themselves. Banana Republic, Gap, and Old Navy have disclosed lists of their subcontractors, including detailed information. This initiative has raised these brands’ transparency to about 44%. However, rather than simply disclosing, it is important to make the information easy to use for consumers, NGOs, labor unions, and workers, and to actually change the current state of labor issues. Very few companies are undertaking efforts to increase transparency, and it is important to expand these efforts to all brands. There are also brands that make clothes through fair trade—buying raw materials such as cotton at fair prices with workers’ livelihoods in mind from the outset—or through fair labor, in which employers and workers set working conditions as equals and do not exploit during the clothing manufacturing process. Examples include People Tree and the Fair Wear Foundation.

Through these efforts at home and abroad, brands are slowly starting to take action. However, as the statistics show, we are still a long way from each brand taking responsibility for its products and eliminating child labor, forced labor, and unfair working conditions. To put pressure on brands and encourage improvement, it will be an important first step for us as consumers to keep global labor issues in mind when buying clothing.

Campaign by Fashion Revolution.By greensefa [CC-BY-2.0]

Writer: Sayaka Ninomiya

Graphics: Sayaka Ninomiya/Yusuke Tomino

服飾産業の問題は私たちが頻繁に購入するような安価なブランドばかりに集中していると思っていましたが、必ずしもそうではなく、値段の問題でもないことがわかりました。

記事中で例に上がっていた「People Tree」のサイトを見てみましたが、やはりいつも購入するブランドと比べると価格が高く、手が出しにくいと感じました。しかし、本来はそれが正しい価格であるはずです。服の買い方について少しずつ自分の欲と向き合っていこうと思います。

ポロシャツで誰が利益を得ているか、というイラストが大変わかりやすかったです。

あまりにも安価な衣服の裏にはやはり人々の犠牲があることを実感します。

諸外国では、サプライチェーンにおける人権を保護する動きも見られますが日本ではまだ進んでいない印象です。そこにはどのような違いがあるのでしょうか?

授業の一環でリサーチしましたが、衣類の大量消費には環境問題だけでなく労働問題も関わっていると知ることができました。