Situated at the cultural crossroads of Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, Bulgaria has a turbulent history. It has been center stage in a history where numerous peoples appeared, disappeared, and then reappeared again and again. Those who conquered this land include the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the Persian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and, more recently, the metaphorically named “Soviet Empire.” Today, however, all this feels like the distant past: this year marks the 10th anniversary of EU membership, prospects for the future are bright, and the country is looking forward to its turn holding the rotating presidency of the EU in 2018.

Within Europe, Bulgaria is known for its Black Sea beach resorts, medieval Byzantine-style monasteries, and quality ski resorts, and this year the capital Sofia is ranked third among European destinations rapidly gaining popularity. In Asia, Bulgaria mainly evokes yogurt and fragrant roses. But not everything is rosy.

Capital Sofia Photo: Boyan Georgiev Georgiev / Shutterstock.com

Future population projections

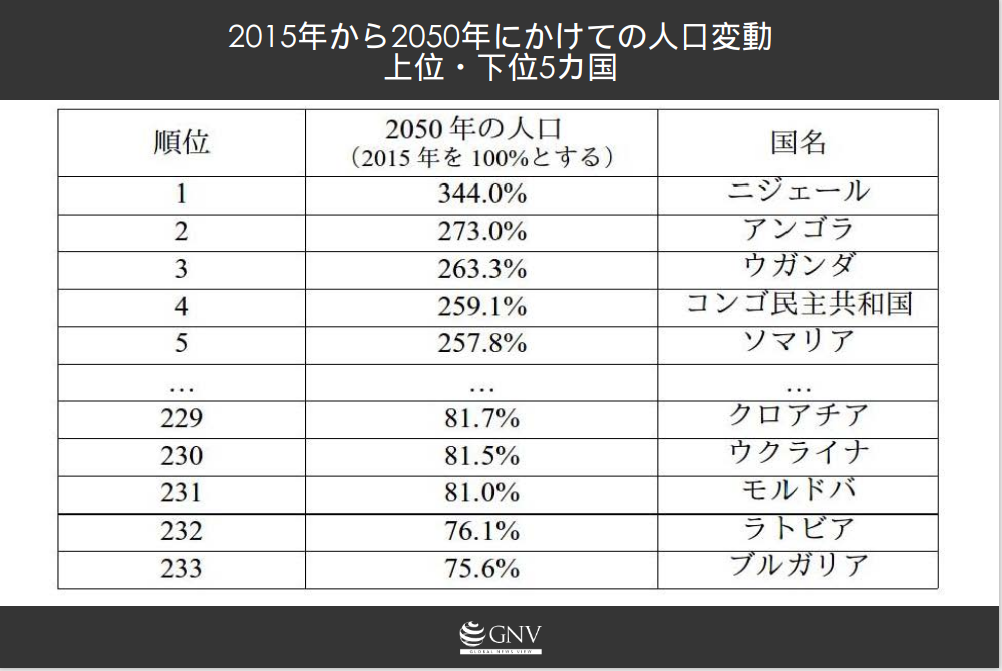

According to the latest UN population projection study, Bulgaria is the country where the population is shrinking the fastest in the world. Between 2015 and 2050, a quarter of the population is expected to be lost, and countries with similarly bleak outlooks are clustered in Eastern Europe. Overall, the world’s population is expected to increase by one third to 9.8 billion, with the fastest growth in Africa; in Niger, the population is projected to more than triple.

Based on data from the United Nations Development Programme

Emigration? Low birth rates?

When the problem of population decline in Bulgaria (and other countries in the region) is covered by foreign media, it is only discussed in the context of migration and brain drain. Indeed, since the end of communist rule in 1989, one major reason the population has fallen from 9 million to 7 million has been emigration. But low birth rates and aging have also played a part.

After World War II, many Europeans emigrated to the “New World,” but in countries under Soviet control ordinary citizens did not have the freedom to move even to other cities, let alone go abroad. If Bulgaria’s millennial generation hears these stories from their parents—how they had to stand in line for hours to buy “foreign” imported goods like bananas—it will feel like a completely different world from today.

With the end of communist rule, and given that emigration abroad had been prohibited until 1989, the migration that unfolded over 45 years in other European countries took place in less than a decade in Bulgaria, a flow that was fueled by the economic crisis arising from democratization and the transition to a free-market economy. About one million people emigrated to Western Europe and the United States, and another one million were lost through natural decrease due to the relationship between low birth rates and mortality. From 1995 to 2000, Bulgaria, together with Latvia, recorded the world’s lowest birth rate (0.8%).

Photo: Ju1978 / Shutterstock.com

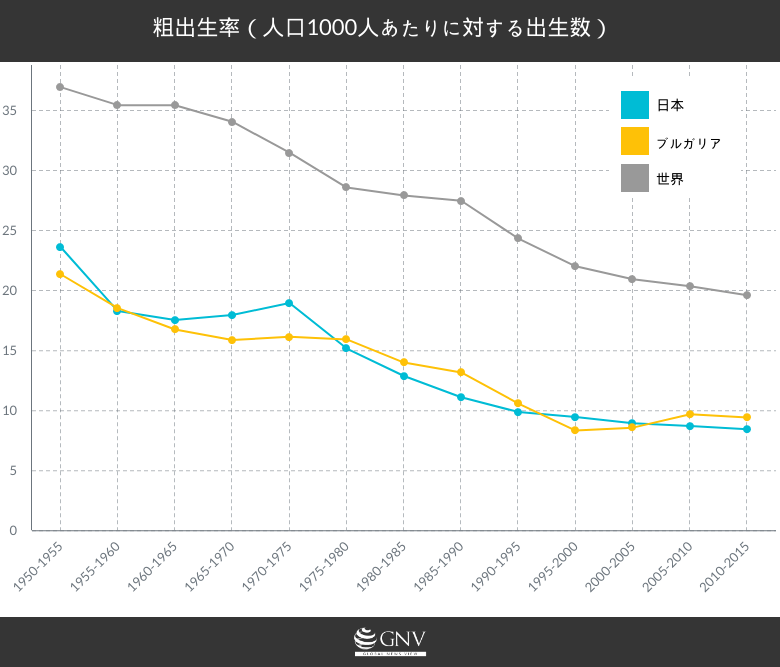

So why are birth rates so low in Bulgaria in the first place? With the exception of Sub-Saharan Africa, where the decline began in the 1990s, since World War II both birth rates and total fertility rates have fallen around the world. The reasons for this phenomenon are not fully understood, but regions with low fertility (Europe and Japan) seem to share similar cultural and social values. That is, relatively low value is placed on religion, parent–child ties, the nation, and authority. These values are called “secular-rational” and are “found especially in states with long social-democratic or social-policy traditions, and where a large share of the population has studied philosophy and science at university.” (See the World Values Survey for details.)

Comparing secular–rational Bulgaria with Japan, which has long ranked at the top on the same indicator, both have followed very similar paths, far below the world average since World War II.

(Based on data from the World Bank)

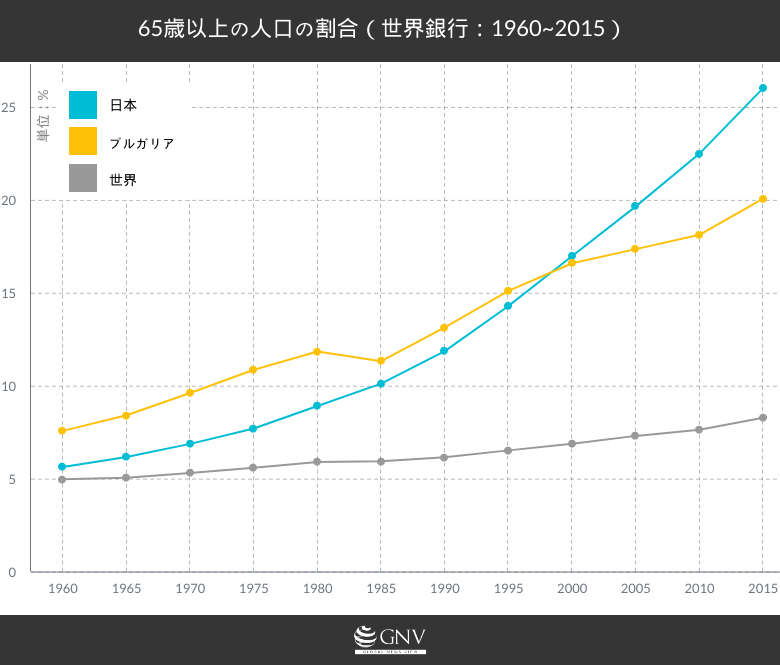

Comparison with rapidly aging societies

Given such very low birth rates and the fact that many young people have emigrated, one might think Bulgaria is aging the fastest in the world. It is indeed among the fastest-aging countries, but no country matches Japan, where those aged 65 and over account for 28% of the population. However, that is largely because life expectancy in Japan is far above the world average.

To look at this in more detail, let’s briefly compare the societies where population is shrinking and aging the fastest.

(Based on data from the World Bank)

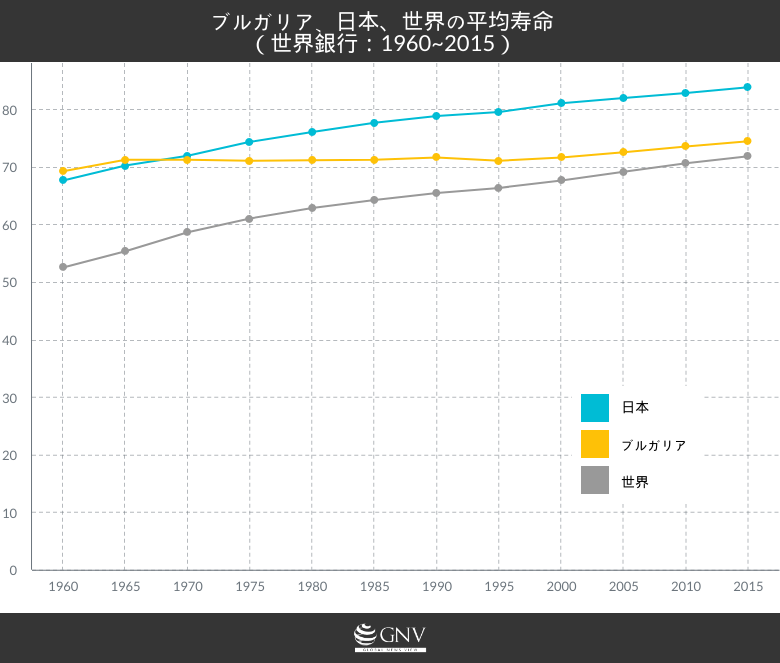

In fact, in 1960 life expectancy was higher in Bulgaria than in Japan. But the devastation under the communist regime and the failures of the transition to democracy caused living standards to fall by half in the 1990s. As a result, life expectancy in Bulgaria did not increase, and is now nine years lower than in Japan. The figure below also shows that there has been little change compared with 1960. Taking life expectancy into account, it is easy to imagine that the aging problem is similarly serious in both countries.

(Based on data from the World Bank)

As this comparison shows, if life expectancy increases, Bulgaria will become an even more rapidly aging society than Japan. And as recent trends suggest—even with limits to longevity—this is in fact already happening.

To make matters worse, unlike Japan, Bulgaria faces problems within the aging cohort: the majority of retirees live below the national poverty level. The rampant inflation of the 1990s wiped out savings, and with no means to earn new income, retirees suffered enormously.

Photo: Dimitrina Lavchieva / Shutterstock.com

Comparing demographic impacts

Given the severe situation in Bulgaria’s demographics, it is also interesting to compare it with the shocks that the two major drivers of population decline in history—war and infectious disease—have had on population statistics.

Over the past 27 years, population decline in Bulgaria has reached 22%, easily comparable to the declines caused by the most tragic modern conflicts. In war-torn Syria, the population is expected to fall by about 13% until it begins to grow again in 2019—from 21 million at its peak in 2010 to 18.3 million next year. Compared with Bulgaria, the period is one third as long, but the magnitude of decline is half.

Even in World War II, the largest share of population loss was recorded by Poland at about 17%, smaller than Bulgaria’s decline to date—and Bulgaria is expected to lose a further 25% of its population over the next 33 years.

In historical terms, the only phenomenon comparable in impact appears to be the global 14th-century Black Death, which reduced the world’s population by a quarter and Europe’s by a third.

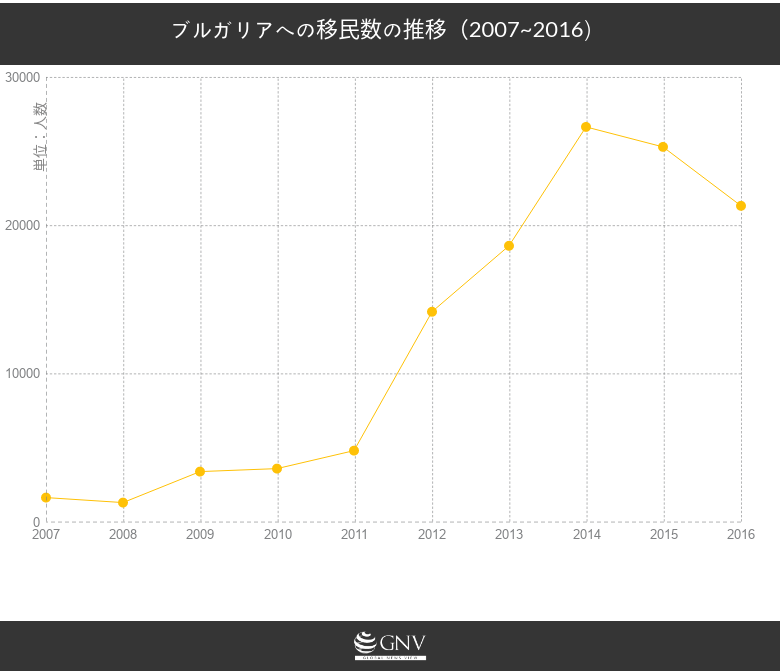

Immigration as a ray of hope?

Judging by the rate of decline, one might think Bulgaria will disappear like many peoples in history. Probably not. Economic improvement and population policies have gradually increased birth rates since the global financial crisis. Bulgaria’s strong economy has also increased the number of immigrants from neighboring countries and reduced out-migration to others. As a result, net migration is heading toward zero and is expected to turn positive in the next few years. In addition, the country’s coasts and foothill mountain regions have mild climates and low living costs, attracting many elderly Europeans who wish to relocate after retirement.

(Based on data from NSI)

Unfortunately, Bulgaria’s per capita income still remains at half the EU average. Migrants to Europe have more prosperous countries to choose from, so a surge of immigration to Bulgaria is unlikely. But the situation is gradually improving. If immigration increases and integration goes well, the landscapes that symbolize depopulation will diminish. Derelict towns and villages with an uncanny sense of isolation; schools and hospitals closing; a workforce that is aging and shrinking; and trains and buses running infrequently due to a shortage of passengers—such scenes are hoped to disappear in Bulgaria and in other societies facing depopulation and aging.

Writer: Yani Karavasilev

Translation: Ryo Kobayashi

Graphics: Eiko Asano

興味深く拝読いたしました。滅多に出会わない情報、ありがとうございます。

感服いたsちじゃおjlぼあ

あ