“Nagorno-Karabakh Republic”—this self-proclaimed independent state, like other sovereign states, has an electoral system and its own currency, and even a president. However, from the standpoint of international law, “Nagorno-Karabakh” is merely a region within Azerbaijan, and no country recognizes it as an independent state. It is not depicted as a state on globes either. Yet after the Cold War, through armed conflict, it achieved de facto “independence.” Since the 1994 ceasefire, only relatively small-scale armed clashes had occurred near the boundary between Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh. However, for the first time in more than 20 years, serious clashes involving civilians broke out in April 2016 and May 2017. It is not appropriate to interpret this simply as a domestic issue within Azerbaijan. A long-standing confrontation between Azerbaijan and neighboring Armenia also lies in the background. Its history goes back to the aftermath of World War I.

Presidential Office of Nagorno-Karabakh Photo: Emena/Shutterstock.com

The rift between Azerbaijan and Armenia

With the collapse of the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, Azerbaijan and Armenia became independent, and at the same time the question of Nagorno-Karabakh’s status arose. This was because, while it was territory within Azerbaijan, most of the people living there identified as Armenian. After World War I, both countries were sovietized and placed under the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Subsequently, under the Soviet Constitution, Nagorno-Karabakh was granted the status of an autonomous oblast within Azerbaijan, but the situation did not settle.

In the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union weakened, calls grew within the autonomous oblast for unification with Armenia. At the same time, clashes began to occur between ethnic Armenians and ethnic Azerbaijanis (Azeris), gradually developing into full-scale armed conflict. In 1991, on the basis of a unilaterally conducted “referendum,” Nagorno-Karabakh declared independence from Azerbaijan as a republic and began claiming ownership of areas beyond the former autonomous oblast. The conflict then intensified further; with Armenian military intervention, Nagorno-Karabakh occupied Azerbaijani territory outside the oblast, and the territory under its control came to connect with Armenia’s border. In 1994, a ceasefire agreement was concluded through Russian mediation, bringing an end to the intense war. The death toll is said to have reached about 30,000, with more than 1 million refugees, according to reports. Today, Nagorno-Karabakh depends on Armenia economically and militarily, but like other countries, Armenia has not recognized it as a state either.

Based on data from Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

What should be noted here is that what took place in 1994 was only a “ceasefire” and did not bring lasting peace to the region. Since then, the confrontation between Armenians and Azeris has continued, clashes have repeatedly occurred around the ceasefire line, and in recent years tensions between the two sides had continued to rise. In April 2016, intense fighting continued in Nagorno-Karabakh for four days, and it was announced that the death toll had reached at least 110. In May 2017, an incident occurred in which, due to an attack by Azerbaijan, an Armenian air-defense missile system installed in Nagorno-Karabakh was destroyed. Why is it that even more than 20 years after the ceasefire, peace has still not come to this region?

Behind the escalation of the conflict

Azerbaijan asserts territorial integrity based on the explicit statements by the UN Security Council and General Assembly that Nagorno-Karabakh and seven occupied regions are Azerbaijani territory. Meanwhile, Armenia argues that the autonomy of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh should be respected. This divergence in views has continued since 1994, but what issues lie behind the further escalation of tensions among Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Nagorno-Karabakh since 2016? First is the domestic economic downturn accompanying the drop in oil prices. Azerbaijan has the Baku oilfields, and oil accounts for roughly 90% of its exports. Armenia, for its part, has no domestic oilfields; with the economic slowdown in Russia, on which it depends, Armenia’s economy has also stagnated, and public dissatisfaction is growing. Under such circumstances, the “Nagorno-Karabakh issue” is sometimes used in both countries as a trump card to divert public dissatisfaction with domestic politics. There is also the view that the deterioration in relations between Russia and Turkey, two major powers influential in this region, is part of the background.

Military parade in Azerbaijan Photo: Sevda Babayeva [ CC BY-SA 3.0 ]

The idea that the current situation must be changed is shared by both Azerbaijan and Armenia, and it is also commonly recognized that this could mean renewed use of force. What clearly reflects this is that both countries are proceeding with further military build-ups. According to a study conducted by a German think tank in 2015, both countries are among the world’s top 10 most militarized states.

Peace talks facing difficulties

Peace talks over the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute are being led primarily by the United States, Russia, and France. These three countries are the co-chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group, which was formed to peacefully resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh issue. The main points of negotiation are threefold: the return of areas occupied by Nagorno-Karabakh outside the original Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, and the return of refugees. Yet even after 20 years, no agreement has been reached on any of these points. According to a survey conducted among residents of Nagorno-Karabakh, about 85% oppose reverting to the Soviet-era boundaries of the autonomous oblast, and only 26% are willing to consider ceding territory to achieve peace. This shows how difficult it is to obtain agreement between the parties.

Summit of Azerbaijan, Russia, and Armenia (2014) Photo: Office of the President of Russia [CC-BY-4.0]

It has been pointed out that repeated failures of peace talks are also due to inadequate ceasefire monitoring by the Minsk Group and a lack of transparency in the peace process. In fact, up to 2017, the area around the ceasefire line between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan was monitored by just six observers, and it is hard to avoid concluding that conflict prevention is insufficient.

The intentions of other countries

Let us consider the Nagorno-Karabakh issue from the standpoint of countries other than the parties involved. The most deeply involved is Russia. While Russia plays a mediating role as one of the Minsk Group co-chairs, it also supplies weapons to both Azerbaijan and Armenia; in Azerbaijan’s case, as much as 80% of imported weapons are said to come from Russia. In the 1990s, Azerbaijan allegedly provided military support to Chechen anti-government forces, worsening relations with Russia, but ties have been improving in recent years. Meanwhile, Russia has a treaty with Armenia and stations troops there, and in the event of an emergency it is to defend Armenia. The purpose behind such actions is to maintain influence in the South Caucasus. As for Turkey, the history of the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian genocide during World War I still casts a dark shadow over the region. Against this backdrop, the border between Turkey and Armenia has been closed since the outbreak of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and diplomatic relations remain severed. By contrast, Turkey and Azerbaijan, which have strong ethnic and linguistic ties, maintain very good relations.

Based on data from Diplomat & International Canada

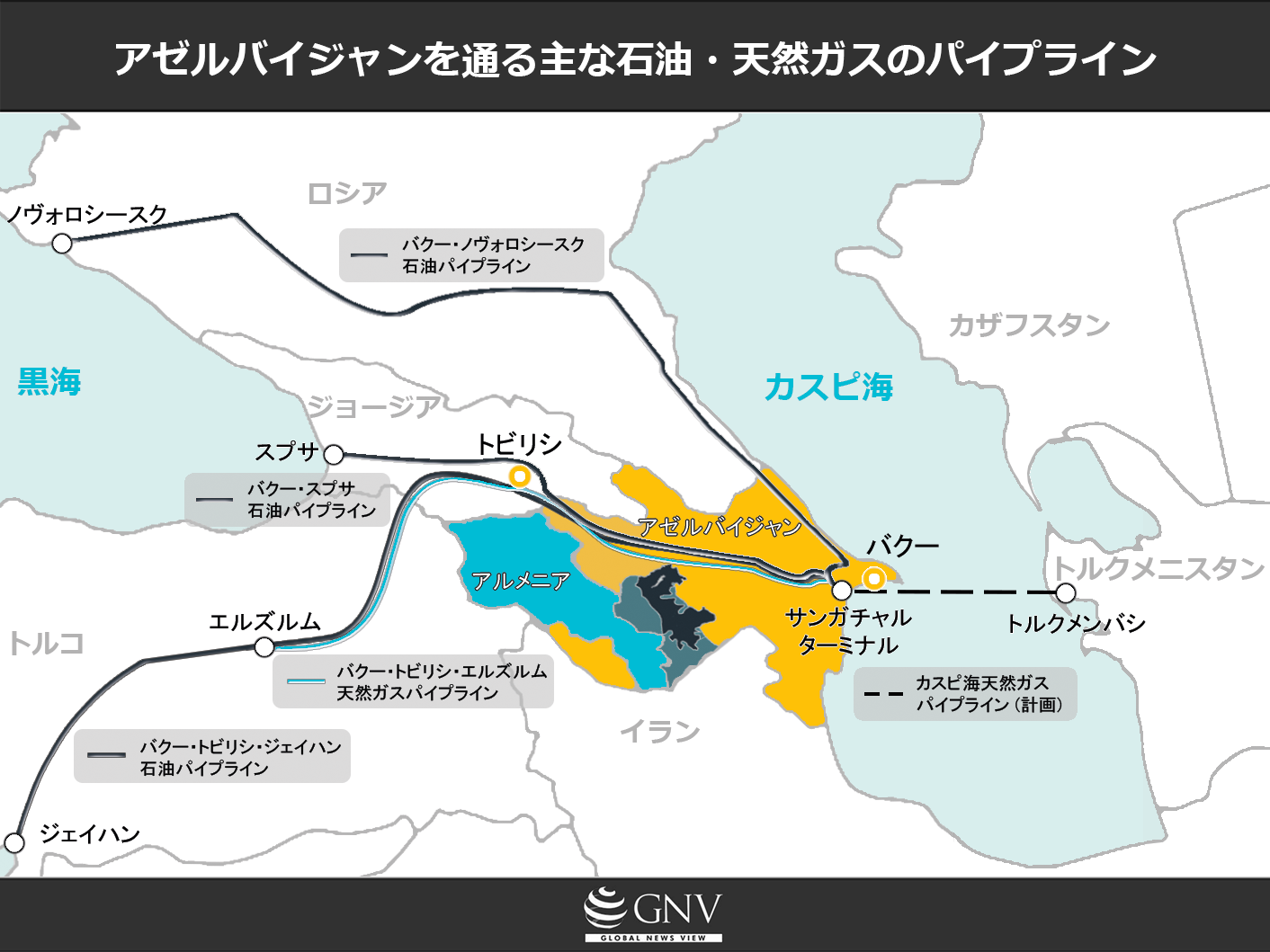

Infrastructure plans by European countries are also one reason the Nagorno-Karabakh issue is subject to outside interference. These plans were conceived as a way to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian energy imports. The Southern Corridor pipeline connecting Central Asia to Europe and the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, which runs from Azerbaijan’s capital Baku through Tbilisi in Georgia to Ceyhan in Turkey, are indispensable to these infrastructure plans. If fighting were to break out in the region, the supply of oil and natural gas through the pipelines would have to be suspended. Thus, Western countries and Turkey want to prevent fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh. Russia, for its part, is wary of such Western infrastructure plans for fear of losing influence over Europe. There is also the suggestion that the continued state of tension in Nagorno-Karabakh benefits Russia. Iran supported the Armenian side during the Nagorno-Karabakh war in the 1990s and still maintains good relations with Armenia. In this way, other countries’ interests—ranging from natural resources to ethnic and historical kinship—are intricately intertwined, making the problem even more difficult to resolve.

Outlook

Conflicts in the former Soviet sphere are often described as “frozen conflicts,” but as we have seen, this is by no means the case; they continue to cause great harm to this day. Precisely because the confrontation between the parties is so deep-rooted, neutral third countries become all the more important. The Nagorno-Karabakh issue is now facing its most tense moment since the 1994 ceasefire. Is it possible to resolve the problem without it developing into a full-scale war? We should keep a close eye on how each country responds going forward.

Stepanakert/Khankendi Photo: Groundhopping Merseburg /Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0]

Writer: Hinako Hosokawa

Graphic: Kamil Hamidov

住民はアルメニア人だったって・・・・じゃあなぜ現在アゼルバイジャン国内に200万人も難民がいるんだ??

別にあんたを誰も信用しなくなるだけだからいいが

初戦はアゼルバイジャンが優勢

ドローンでアルメニアの防空施設を破壊

中国で絶対の信頼を誇ってるロシア製Sー300が木っ端微塵に、ドローン攻撃のすさまじさを世界にしめした

おかげでいまや両軍とも砲撃戦に意向、砲弾とフェイクニュースを撃ち合ってる