In February 2016, the Bangladesh central bank heist laid bare to the world the close nexus between illicit funds and casinos.

The perpetrators first hacked the Bangladesh central bank’s systems and attempted to transfer nearly US$1 billion from its account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to bank accounts in the Philippines and Sri Lanka. Although the US$20 million sent to Sri Lanka was successfully recovered due to an entry error by the perpetrators, a portion of the US$81 million (about 9.1 billion yen) that went to the Philippines subsequently flowed into casinos, making it untraceable and impossible to recover.

Why did the money “disappear” in the casino? Because in casinos, where funds are constantly circulating between the house and customers, tracking the fate of funds brought in by a single individual is difficult. In addition, banking-like services offered by casinos—deposits, currency exchange, remittances, foreign exchange, cash advances, and check cashing—further complicate the movement of money within casinos. Records of fund movements that would be clearly kept at a bank are lacking, making it easier to evade government regulation and oversight. In other words, the very nature of casinos is not merely that people enjoy gambling; they inherently carry the risk of facilitating crimes involving “dirty money.”

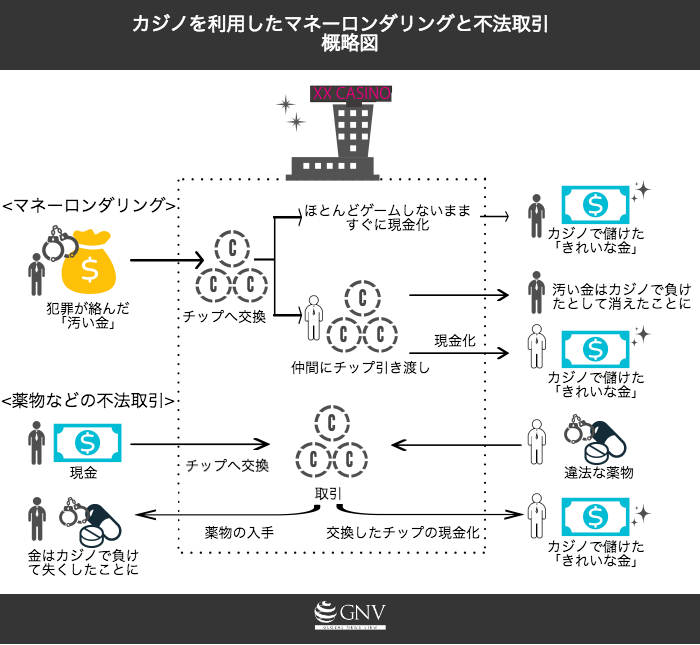

Accordingly, when it comes to money laundering and illicit transactions, there are many specific cases and methods by which casinos are used. However, the role of casinos in the handling of illicit funds can be summed up in two points: producing clean money and making dirty money disappear. Money obtained through theft, embezzlement, or bribery can be claimed, upon exiting the casino, to be “clean” money simply won through gambling. Also, by handing chips purchased with illicit funds to accomplices inside the casino, that dirty money appears, on the surface, to have been lost in bets and to have vanished. Meanwhile, when illegal transactions such as drug deals take place inside casinos, chips may be used in place of currency. The money entering the casino itself is not dirty, and the amount used in the transaction can be claimed to be gambling losses, making it difficult to detect.

As “safe” financial institutions for the handling of illicit funds, casinos gain further significance due to their cross-border nature. In the 2015 ranking by company revenue, No. 1 was “Las Vegas Sands” (U.S.) and No. 2 was “MGM Resorts” (U.S.), and both companies operate globally, including in the United States, Macau, and Singapore. Some companies have systems that allow chips or checks purchased at one property to be redeemed at another, making international transfers easy. In recent years, online casinos have also seen rapid growth, and electronic payment systems have further accelerated this ease.

In addition, the intermediary presence known as “junkets” makes the movement of funds even more complex and opaque. A junket is an intermediary organization that plans and operates tours to casinos and supports customers’ travel in all respects, such as accommodations and transportation. Some are run by casinos, while others are separate organizations. The existence itself is not a problem, but at times they play the role of “couriers,” funneling illicit funds abroad or outside legal constraints. For example, although there is a limit on the amount of money that can be brought from mainland China into Macau, by depositing money with a junket before departure and then receiving the funds at a Macau casino after they have been transported by ferry separately from the customer, junkets have greatly facilitated money laundering by Chinese officials.

Finally, the secrecy of casinos further increases their utility to actors attempting to handle illicit funds. Casino operations are heavily dependent on VIPs and high rollers; for example, in Canadian casinos, 80% of revenue comes from the top 1% of VIP customers. Because of this reality, casinos cannot bring to light what happens in VIP rooms and have tolerated wrongdoing even when they witness it, and at times have actively concealed it. Moreover, there are cases where criminal organizations become casino owners themselves. In any case, it is certain that both VIPs and casinos have reaped large profits by making use of the secrecy of VIP rooms.

Inside a casino Photo: Municipalidad de Talcahuano/flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Given that casinos have become hotbeds for the handling of illicit funds, AML/CFT (Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism [Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism]) measures targeting casinos have been strengthened globally in recent years. The AML/CFT movement began with the launch at the 1989 G7 Summit of the intergovernmental organization FATF (Financial Action Task Force [Financial Action Task Force]) to combat money laundering, and subsequently came to include efforts to counter the financing of terrorism, on the grounds that uncovering and cutting off terrorist organizations’ funding channels to prevent attacks overlaps with anti–money laundering measures. Currently, in addition to working in cooperation with the IMF, regional bodies such as the APG (Asia-Pacific Group on Money Laundering) are also active.

The stated policy goals for introducing casinos include job creation at integrated resorts (IRs) that include casinos, attracting tourists, and, as a result, promoting regional economic development. However, the flow of capital from advanced economies into developing regions in Asia and Africa to build casinos can also look like a search for new locations that evade regulatory scrutiny. Debates about the harms of casinos are often focused on gambling addiction and the poverty it can cause, but we should be even more concerned about casinos becoming safe havens for criminal organizations and individuals engaged in wrongdoing, and the danger that they will build global networks. For example, Macau’s economy has depended on revenue from casinos and related facilities, but over the past two years, due to the Xi Jinping administration’s anti-corruption drive, its core customers—Chinese officials—have stayed away, and revenues have plummeted. This has laid bare how reliant casinos have been on the “dirty money” born of their corruption.

Even if it is in the name of economic development, who is truly benefiting from casinos? Local residents, casino operators, VIPs who cross borders to visit, or criminal organizations? Just outside Macau’s glittering buildings, dilapidated houses await.

Casinos and surrounding houses (Macau) Photo: doviliux/pixabay

Writer: Miho Kono

Graphics: Miho Kono

初めて考える視点で、大変興味深く読みました。表面上の議論に留めず、より本質的な問題に目を向ける必要があるのだと分かりました。