Conflicts currently unfolding around the world are claiming many lives. In recent years, those in Yemen, Iraq, Syria, the Central African Republic, Nigeria, and South Sudan have been particularly large in scale, and deaths from conflict in 2015 are estimated at 167,000. But this reflects only a portion of conflict-related deaths. That figure counts people killed by direct acts of violence and excludes deaths caused by the side effects of conflict, such as hunger and infectious disease. In fact, the number of people who die for reasons other than combat is enormous. Yet for many conflicts, no studies have assessed how large that toll is. For a variety of reasons it is difficult to determine, and we still do not have a grasp of how many people worldwide have truly lost their lives to conflict in recent years.

Destroyed city, Aleppo, Syria — IHH Humanitarian Relief Foundation Azez, Aleppo (3) ( CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 )

Here, I would like to revisit how people lose their lives in ways other than combat when conflict erupts.

As a premise, conflict is a complex social phenomenon. When it breaks out, social services such as water, electricity, gas, and healthcare are suspended, and shops that supply food, such as supermarkets, also shut down. Transportation networks are thrown into chaos; there are no medical workers and no medicines arrive. Beyond the physical harm from gun battles, the destruction of towns and villages devastates the infrastructure that sustains daily life. As a result, even if people manage to escape, they lack the food to live on and the medicines to treat injuries. Sanitation deteriorates and infectious diseases spread. Even for those fortunate enough to reach a refugee camp, high population density and insufficient support often lead to outbreaks of disease. This is how lives are lost.

In fact, in many recent conflicts, deaths from such indirect effects of conflict (hereafter “indirect deaths”) outnumber deaths from violence (hereafter “direct deaths”).

Across the 13 conflicts listed in the table above, more than 60% of total deaths were indirect in all but the Kosovo conflict. Notably, the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo—the largest since World War II—caused about 5.4 million deaths between August 1998 and April 2007; less than 10% were direct deaths, and 90% were indirect, according to statistics. Although parts of the conflict continue, no further mortality surveys have been conducted. By contrast, the near absence of indirect deaths in Kosovo can be attributed to relatively robust resilience: pre-conflict infrastructure and living standards were high, and social protection services in places of refuge inside and outside the country were well developed. Moreover, the conflict drew international attention up to the point of U.S. and NATO intervention, and large amounts of humanitarian aid were delivered. In 1999, when both Kosovo and the DRC were experiencing conflict, per-capita aid was US$207 for the former versus US$8 for the latter—a stark contrast. Seen another way, indirect deaths in conflict may be preventable through better infrastructure, higher living standards, and humanitarian assistance. The need for such assistance has been rising in recent years.

Financial Tracking Service data was used as the basis

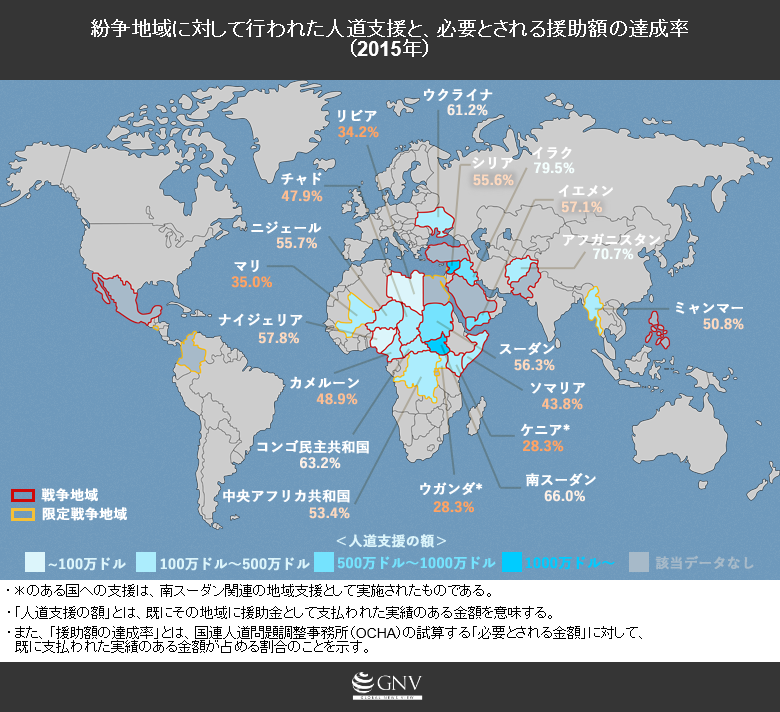

Data from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs indicate that, as of December 2016, the UN estimated about US$22 billion would be needed to assist approximately 96 million people targeted for aid worldwide. This far exceeds last year’s figures of US$20 billion for 83 million people. However, despite the magnitude of need, the assistance that can actually be delivered is limited. Of the $22 billion required this year, as of December 8 only 53%—just over $10 billion—had been funded. Moreover, the population in need of some form of assistance is estimated at 130 million, exceeding the number of people targeted for aid. This is because the UN defines “people targeted” by considering factors such as the severity of the situation, whether access can be secured to deliver aid, and whether the scale of harm exceeds what national authorities can address.

For conflict-affected areas, created based on data from the Conflict Barometer; for humanitarian funding amounts and funding rates, created based on data from the Financial Tracking Service.

Writer: Yusuke Sugihara

Graphics: Yosuke Tomino, Miho Kono

こうゆうグラフは助かります。