Some unsettling developments are occurring on the Balkan Peninsula in southeastern Europe.

The Bosnian War (1992–95) claimed around 100,000 lives. In response to the breakup of Yugoslavia, in March 1992 Bosnia and Herzegovina held a referendum on independence. While the majority of Bosniaks (44% of the population at the time) and Croats (17%) favored independence, many Serbs (33%) who opposed it boycotted the vote. Amid deepening interethnic tensions, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence. The following month, military clashes broke out, escalating into the Bosnian War. Because each group aimed to expand its own ethnic sphere of control, the conflict took on the character of a “land grab.” Consequently, to secure stable ethnic strongholds, “ethnic cleansing” was carried out, and in Srebrenica, which the United Nations had designated a “safe area,” more than 8,000 people were systematically killed in a massacre. From 1994, NATO launched air strikes against Serb forces, depriving them of the ability to counterattack and prompting them to engage seriously in peace negotiations. In November of the following year, the parties to the conflict signed the Dayton Peace Agreement, bringing the war to an end.

Sarajevo in 2001. Scars remained even several years after the end of the conflict (Photo: Virgil Hawkins)

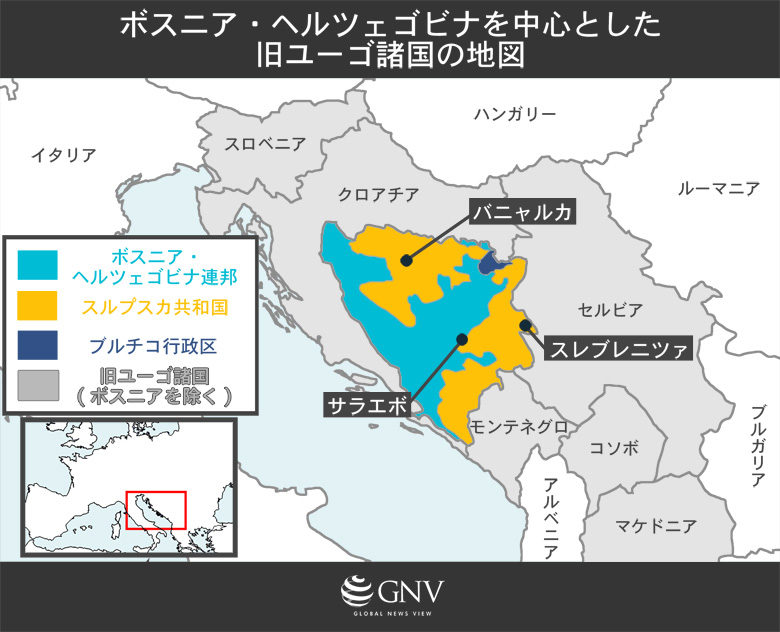

As a result of the agreement, the country became a single state composed of two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, centered on Bosniak and Croat residents, and Republika Srpska, centered on Serb residents. In addition, during the signing of the Dayton Agreement, the Brčko District, which belongs to both the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, was also established.

The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska are highly decentralized, with each entity having its own president and government, and today the two coexist domestically as a state union that outwardly constitutes a single country. Even now, 20 years after the end of the conflict, as part of the implementation of the peace agreement, the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina, who oversees civilian aspects of peace implementation, remains in place, and the EU military force (EUFOR Althea) has also been deployed, so it continues to receive support from the international community. It was also supposed to be making peaceful progress as a country toward the goal of joining the EU.

Source: Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina

However, in reality, tensions among ethnic groups continued to exist even after the peace agreement. Discrimination against non-Serbs has been particularly conspicuous in Republika Srpska, where it has been reported that non-Serbs have been victims of violent crime more than ten times as often as Serbs. In 2002, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) reported incidents of violence against non-Serbs in Republika Srpska and the involvement of police in them.

Amid this, an event occurred that further heightened tensions. On September 25, 2016, a referendum was held to uphold the national day. The national day in question had been unilaterally introduced by Republika Srpska, which is centered on Serb residents, and refers to January 9, a religious holiday of the Serbian Orthodox Church. In response, the Constitutional Court in Sarajevo ruled that establishing the holiday would lead to discrimination against non-Serbs, declared it unconstitutional, and ordered the national day to be abolished. President Milorad Dodik of Republika Srpska resisted the ruling. On September 25, Republika Srpska held a referendum to maintain the national day.

According to the referendum results, voter turnout was 55.8%, and about 99.8% voted to reject the Constitutional Court’s ban on designating the national day. President Dodik declared that “we have inscribed a glorious page in history,” indicating his intention to continue to mark January 9 as the national day.

The reason Republika Srpska is so fixated on the national day is the underlying intention to achieve independence from Bosnia and Herzegovina. There are concerns that holding the referendum and establishing the national day could become a stepping stone for Republika Srpska to secede from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

It is not only the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina that finds these moves by Republika Srpska undesirable. The United States and the EU have argued that establishing the national day violates the Dayton Agreement, and have called on Republika Srpska to accept the Constitutional Court’s ruling and called for the cancellation of the referendum. They fear the independence of Republika Srpska. An EU foreign policy official stated, “The referendum has no legal basis and therefore cannot overturn the ruling of unconstitutionality,” adding, “We will support resolving this national day issue through legal processes and constructive dialogue.”

Surprisingly, the government of the Republic of Serbia, which has an alliance with Republika Srpska, opposed the referendum. As Serbia seeks EU membership, it could not support the establishment of a holiday opposed by the EU. Meanwhile, President Putin of Russia declared his support for holding the referendum. This shows that developments in Bosnia and Herzegovina are attracting attention from other countries as well.

Since before World War I, the Balkan Peninsula has been called the powder keg of Europe. The armed conflict has ended, but the underlying problems remain deeply rooted. Today’s Bosnia is very different in many ways from Bosnia 100 years ago or 25 years ago. However, the current political confrontations and interethnic frictions are cause for concern. We cannot take our eyes off Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Balkan Peninsula in the time ahead.

Writer: Ikumi Kamiya

Graphics: Mai Ishikawa

0 Comments