The shrimp commonly eaten in the United States, Japan, and Europe are supported by victims of human trafficking occurring in Southeast Asia. How many people are aware of this shocking fact?

The major U.S. news agency the Associated Press (AP) exposed this fact to the world after more than 18 months of tracking ships. The investigation they reported in 2015 became a major turning point, and the involvement of sea slavery in shrimp harvesting began to be recognized as an international issue.

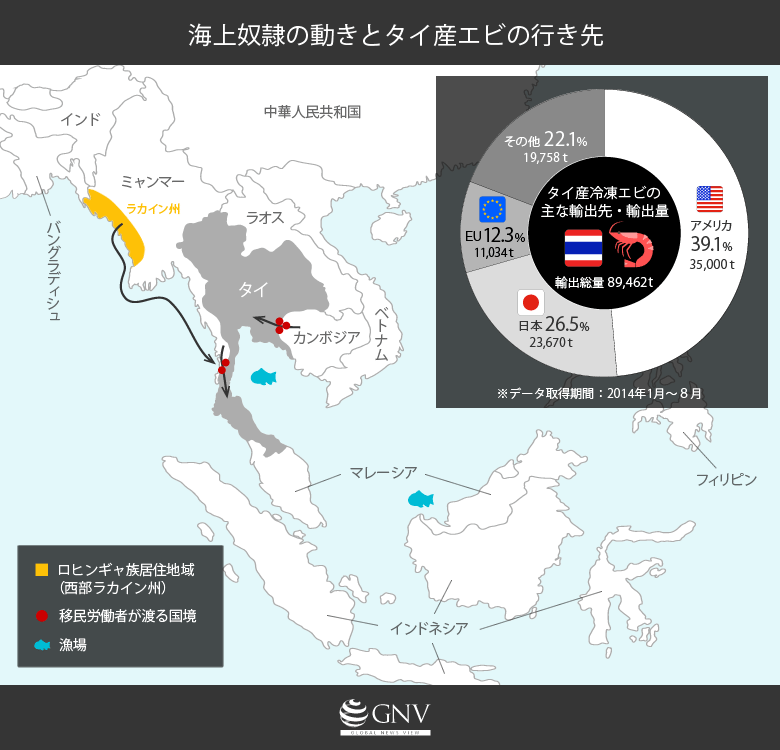

Furthermore, the UK newspaper the Guardian alleged, based on a six-month investigation, that Thai shrimp around the world includes the products of slave labor. For one, the internationally known Thai multinational food company CP Foods is said to supply shrimp caught by sea slaves to membership warehouse stores such as Costco, founded in the United States. This is one example of how shrimp are supplied at low prices from Thailand to the United States, Japan, European countries, and China.

Shrimp (Photo: Peter Griffin [ CC0 1.0])

People who become sea slaves on Thai fishing boats are often migrant workers from neighboring Myanmar and Cambodia. They are frequently socially vulnerable individuals seeking jobs to escape persecution and poverty in their home countries. Numerous investigations have revealed the following pattern by which they become victims: in harsh living conditions without funds to make a living, they hear of good jobs, trust brokers’ illegal labor assistance, take falsified travel documents for foreign or distant work locations in hand, and board a boat. But where they end up is an environment different from the contract, where they are forced to work long hours under harsh conditions aboard boats floating on the high seas. Furthermore, they are forced by the captain to drink dirty water, and in extreme cases are detained and made to work up to 20 hours a day without rest. Not only at sea; on land, women and children may be involved in peeling and processing shrimp before export. Their identification is confiscated, and the documents they are given are often fake; in addition to the disadvantage of having no legally valid identification, the fact that they are on ships from which they cannot escape and in places out of the public eye makes it difficult to flee. Even after they learn of the deception, they continue to work away from their families and home countries for several to more than ten years under a written contract, for a monthly salary of $50 (approximately 5,100 yen as of September 9). After the problem came to light, there have been cases of rescue, including one person freed after 22 years of labor, but there are still many victims.

This labor issue, born of low social status and poverty, is complex. Beyond simple poverty, factors include the ambiguity in the application of labor laws on the high seas; companies in developed countries seeking cheap shrimp and the subcontractors in developing countries that mediate for them; relationships between workers and companies; and the supply chains among companies at the export destinations.

The fact that Myanmar and Cambodian people become slaves in the seas of Thailand and Indonesia is sometimes intertwined with ethnic issues stemming from different religions, as well as political issues. In Buddhist Myanmar, about 1.1 million members of a minority called the Rohingya live in Rakhine State in the west near Bangladesh, where many Muslims reside. Because their Islam differs from the national religion, among other reasons, the Rohingya are of low status and persecuted in the country. It has been reported that the situation has reached a stage where mass killings could occur. Even if Rohingya flee to neighboring Thailand, Thailand is not a party to the Refugee Convention and lacks a system for protecting refugees, so they are treated as illegal entrants. Thus, even where they flee, lacking status and seeking work and a livelihood, they become victims of human trafficking and exploitation.

Looking next at the characteristics of the countries involved from an economic perspective, Thailand, for example, trades with developed countries such as Japan and the United States, and among 25 Asian countries in fiscal 2014 ranked 7th in nominal GDP and had a per-capita nominal GDP of about $5,889, indicating a relatively good economic situation. By contrast, Myanmar, which was under military rule for several decades, ranked 16th in nominal GDP and had a per-capita nominal GDP of about $1,278, and large-scale violations of basic human rights and of labor unions still exist. Because of these differences, it is highly advantageous for Thai companies to use Myanmar workers, whose domestic wages are lower than Thailand’s, and many migrant workers from Myanmar are employed in Thailand’s fishing industry. Shrimp produced using this inexpensive labor are exported mainly to major developed countries and end up on dining tables and in supermarkets.

Table: (Based on data from SiamCanadian) Explanatory map: (Based on an article by National Public Radio)

As of now, according to an article reported on September 17, 2015, AP’s reporting served as a catalyst, prompting action by the Indonesian government and the IOM (International Organization for Migration), and in six months more than 2,000 people from Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos were rescued. According to AP, in response to the exposure of the horrific situation, in February 2016 President Obama decided to ban the import of more than 350 slave-produced goods, including seafood from Thailand and Indonesia, taking a major step toward solving the problem. Nevertheless, Thailand, the country concerned, although it has declared that it will work toward a solution, still appears reluctant to take concrete action or enforcement.

Migrant workers on Thai fishing boats (Photo: ILO in Asia and the Pacific [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

This sea slavery issue has multiple causes, including corporate profits and inter-state disparities that exist both within Southeast Asia and between developed countries and Southeast Asia, and simply carrying out rescue activities will not lead to a fundamental solution. From the perspective of companies in Thailand and Indonesia, they are likely unable to move quickly to enforce labor systems in order to secure corporate profits, and by extension, national interests. Consequently, the governments of Thailand, Indonesia, and others, and the developed countries at the other ends of their supply chains, may also find it difficult to strictly crack down on these human trafficking brokers and the companies involved. The world as a whole needs to review and improve the international labor system, and to establish more detailed regulations for the inadequately governed area of maritime labor, so that sea slavery does not occur in the future.

Writer: Aki Horino

Graphics: JT-FSD

わかりやすくまとめられた記事で、東南アジアの水産業の労働実態と、その要因がわかりました。

結局は弱者が悪い労働環境に追いやられやすい、ということなのだと思います。弱者は教育を受けられず騙されやすい、弱者は自国で迫害され不法移民にならざるを得ない、弱者は所得が少なくどの労働に従事せざるを得ない、というようなことですね。

具体的に企業にアクションを取ってもらうために何が必要なのか考えていますがなかなか答えが見えません。