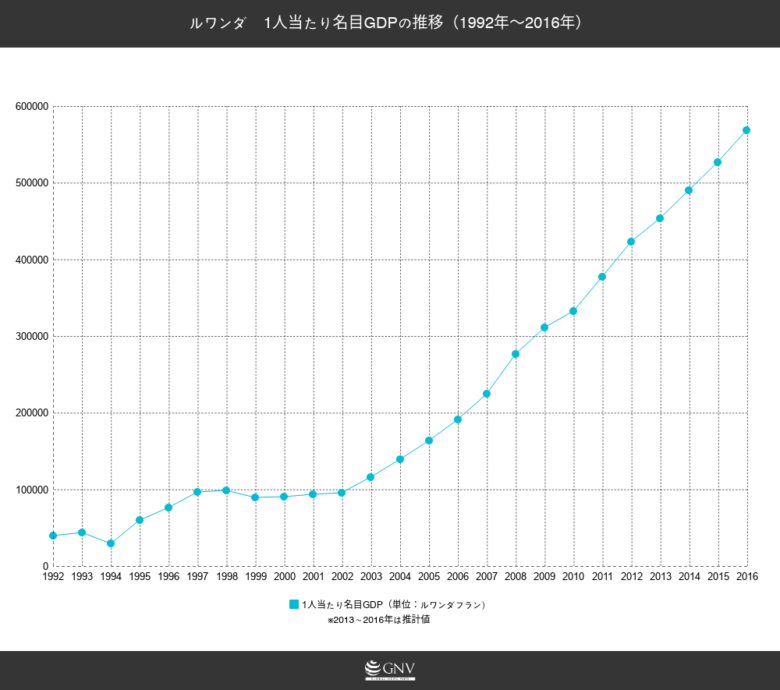

More than twenty years have passed since the genocide in Rwanda that claimed over 800,000 lives. Since then, no renewed conflict has occurred within Rwanda, and the country’s nominal GDP per capita has achieved steady year-on-year growth.

Based on data from “World Economic Data Book”

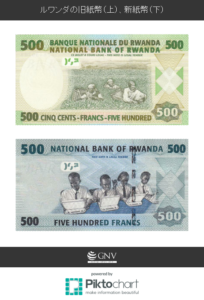

One factor behind this is development in information technology (IT). With few mineral resources and, as a landlocked country, no ports, Rwanda has pursued success through an information-intensive economy. This is reflected even on its banknotes: the banknotes redesigned in 2013 replaced an image of a woman picking tea leaves with children using a computer, reflecting the government’s intent to steer the country toward becoming an IT nation.

Beyond the economic dimension, there are other noteworthy aspects. On the Human Development Index, calculated from national levels of health, education, and income, Rwanda has seen the greatest increase over the past 25 years compared with other countries. As a result of a rigorous crackdown on bribery, Rwanda is regarded as the least corrupt country in Africa. It has also achieved many other outcomes, such as the highest proportion of female parliamentarians in the world. These achievements across many sectors, including the economy, have been called the “African miracle.”

The person who has driven this growth with strong leadership is Rwanda’s president, Paul Kagame. Even before the genocide, Kagame was a central figure in the Tutsi-led rebel group, the Rwandan Patriotic Front. After the mass killings of Tutsis by the Hutu majority ended, he led the movement to seize power. Since then, for more than 20 years, he has held the real power in Rwanda.

Kagame has been praised by dignitaries around the world for achievements like those mentioned above. However, various shadows can be glimpsed behind these accomplishments. One is the two invasions of the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) in 1996 and 1998. When the Rwandan Patriotic Front took power, more than two million Hutus (including both refugees and participants in the massacres) fled to eastern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). From these sanctuaries, Hutu rebel groups launched attacks against the Rwandan government, prompting Rwanda to move to suppress them. As a result of the ensuing invasion, the Zairian regime collapsed and the country was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This series of upheavals was the First Congo War. The conflict in the DRC appeared to have ended, but a year later, in 1998, Rwanda invaded Congo again. The war expanded to involve eight countries in total, including Uganda, Burundi, Angola, and Zimbabwe. The death toll from this conflict exceeded 5.4 million, making it the deadliest conflict since the Cold War. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Kagame administration bears heavy responsibility for having set this chain of events in motion.

Caption: Map of Second Congo War, 2001–2003. Authors: Don-kun, Uwe Dedering Source: Own work by the contributor, derivative of File:Democratic Republic of the Congo location map.svg CC BY 3.0

Another deep-seated issue is that, once the conflict settled into a stalemate, Rwanda led the Congolese rebel group Rally for Congolese Democracy–Goma (RCD-Goma) and controlled eastern DRC—an area many times the size of Rwanda’s territory.

Moreover, together with Uganda, it carried out the exploitation and plunder of diamonds, coltan (a natural mineral used as a component in electronic products), timber, and ivory. And this occupation continued until the 2002 peace agreement.

In fact, it has been shown that Rwanda’s exports of mineral resources increased during the war, and that it received far more aid from developed countries than its neighbors. These factors have been major drivers of Rwanda’s economic development.

Beyond such interference in other countries, there is also the reality of an oppressive domestic rule that could be called a reign of terror.

President of Rwanda, Paul Kagame. Caption: H.E. President of Rwanda, Paul Kagame at the 9th Broadband Commission Meeting, Dublin 22–23 March 2014. Photo by ITU Pictures

One glimpse of this reality came in the 2010 presidential election in which Kagame was re-elected. In that election, Kagame won an astonishing 93% of the vote to secure another term. In the same election in 2003, Kagame won 95% of the vote. There are facts suggesting these two unnatural numbers may be false. In the 2010 election, there was a region where Kagame’s vote share was only about 10%. However, one of the election commissioners reported that the local leader, fearing for his position, manipulated the vote results. From this leader’s actions, it is easy to infer government pressure on local administrations.

Furthermore, Kagame has severely curtailed freedom of the press and expression through strict controls. In Rwanda’s media, there are almost no articles that question or criticize the current regime or presidential elections. Even slightly critical content is met with immediate repression by the government; journalists are imprisoned, forced into exile, or, in the worst cases, killed. By imposing such a system, Kagame has maintained overwhelming approval ratings. There are also reports that he has threatened and imprisoned political opponents and anti-government figures, and even assassinated them. Kagame exercised authoritarian leadership to pull off the so‑called “African miracle.” But at the same time, by suppressing the human rights of those who oppose him and muzzling the press, he has fashioned a Rwanda to his own convenience.

It cannot be denied that such forceful leadership may have been what made Rwanda’s development possible. Even taking that into account, however, it is hard to turn a blind eye to the realities of this oppression.

Rwanda’s next presidential election is coming up next year. Traditionally, the president’s term in Rwanda was limited to two terms, and a third term was constitutionally prohibited. However, in 2015 Kagame amended the constitution, making it possible for him to remain president until 2034. Even the United States, which had long praised Kagame’s reforms since the genocide, has opposed this re-election and urged him to step down. In response, Kagame commented, “The people want me to be president beyond 2017, and I am simply accepting that,” and he has not wavered in his bid for a third term. We must keep a close eye on next year’s presidential election in Rwanda and developments surrounding it.

Rwanda’s capital: Kigali (Dereje, shutterstock.com)

Writers (GNV): Sota Dokai, Shiori Yamashita, Hiro Kijima

Graphics: Sota Dokai

0 Comments