The end of the Cold War symbolized the notion that the ideological competition between capitalists (the right) and communists (the left) had been permanently settled by a sweeping victory for the former and the erasure of the latter. As the “winner” of the Cold War, the United States appeared to have convinced the world that the right was correct. But Latin America was different. Clinging to history, it swung like a pendulum between the “right” and the “left.”

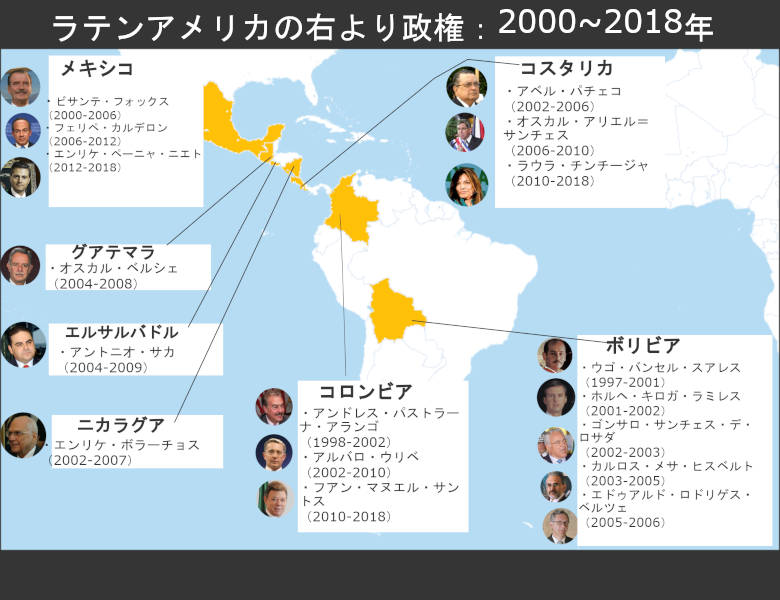

In the early 2000s, right-wing neoliberal governments (※1) were dismantled one after another through popular elections, and left-wing governments came to power. This regionwide political movement was called the Pink Tide, a nod to the so-called “Red Tide” that evoked revolutionary left-wing governments. “Pink” was used to indicate a somewhat lower degree of communism/socialism than “red,” hence Pink Tide. About a decade later, when the Great Recession began in 2008, Latin America again showed signs of a rightward shift. But rising political pressure for social reform, economic discontent under right-wing rule, and the devastation of COVID-19 tilted Latin America back to the left. A new Pink Tide became the topic of discussion. Latin America once again stood at the forefront of a large-scale political experiment.

Organization of American States, 2022, Peru (Photo: U.S. Department of State / Flickr [United States government work])

目次

The Politics of the Pink Tide

In 1998, in Venezuela, a poor country with the world’s largest oil reserves, Hugo Chávez was elected and the Pink Tide began. His clear agenda of “rebuilding socialism for the 21st century” sent ripples—mixing enthusiasm and pessimism—across the region. For ordinary people, it offered a path out of hardship; for capitalists, it was a threat. The following year in Chile, Ricardo Lagos, a leftist who had opposed former dictator Augusto Pinochet, was elected president.

The Pink Tide gathered momentum the following year and rapidly swept Latin America. In 2003, the charismatic leftist leaders Néstor Kirchner of Argentina (succeeded in 2007 by his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner) and Lula da Silva of Brazil rose to power. Panama (2004), Uruguay (2005), Bolivia (2006), Peru (2006), Honduras (2006), Nicaragua (2007), Ecuador (2007), Paraguay (2008), Guatemala (2008), El Salvador (2009), and Costa Rica (2014) followed. The Economist reported with a hint of concern that by 2023, 12 of the 19 countries accounting for 92% of Latin America’s population were under left-wing governments.

It is not always possible to fit the Pink Tide’s leaders into a single ideological box. At a minimum, all of these leaders supported broad political and economic policies that assigned the state an active role in national development and the provision of social welfare. They recognized the importance of expanding political participation to address the urgent needs of working-class and marginalized communities, rejected neoliberal dictates, and sought to minimize international (especially U.S.) interference in domestic affairs. In practice, however, Pink Tide leaders articulated their left positions in many shades—from radical socialism as with Venezuela’s Chávez to moderate leftists like Uruguay’s José Mujica. Clearly identifying the ideological tendencies of Latin American politicians is not easy.

Some scholars argue that this ideological diversity has been a major obstacle to forming a strong regional bloc capable of countering influential outside forces internationally. In 2004, Venezuela and Cuba established the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas (ALBA: Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos) as a regional platform to counter external influence. Not only did countries closely aligned with the United States—Colombia, Mexico, and Peru—decline to join this new move, but so did Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay. Ecuador announced its withdrawal in 2018 when a centrist president replaced a leftist one. Geopolitical disputes among Latin American countries, such as the Bolivia–Chile border dispute, were also among the causes of this fragile regional solidarity.

The Economy of the Pink Tide

At their peak, Pink Tide governments achieved remarkable results. Under Chávez in Venezuela, for example, the unemployment rate was cut in half, from 14.5% in 1999 to 7.6% in 2009, and extreme poverty fell from 23.5% in 1999 to 8.5% in 2011. Brazil under Lula (2003–2010) boasted that it had rescued 20 million Brazilians from unemployment. Another example is Evo Morales, the first Indigenous leader elected president in Bolivia. He achieved average annual economic growth of about 4.9% and reduced the poverty rate from 59.9% in 2006 to 34.6% in 2017. Numerous reports suggest that the Pink Tide is associated with reductions in poverty in Latin America. In the region, left-wing governments succeeded in reducing income inequality faster than non-left governments.

Pink Tide governments reduced poverty and improved public health and literacy by raising minimum wages and launching social welfare projects such as conditional cash transfers. These governments financed such measures through commodity trade revenues (especially oil, gas, and mining) and external borrowing. It has been noted that this favorable international environment was partly propelled by increased demand accompanying China’s economic rise.

Riding the commodities boom, most Pink Tide governments promoted policies for natural resource extraction aimed at export, but one could say this only reaffirmed the region’s role as a supplier of primary goods to international markets. They remained dependent on export and resource sectors and failed to develop a strong industrial base to raise productivity and diversify their economies. The export-led strategy exposed the region to the vulnerability of price fluctuations in global markets. For example, Latin America’s trade with China (oil, copper, iron ore, soybeans) averaged about $106 billion per year from 2003 to 2013, with much of it dependent on Chinese demand. When China’s economy began to slow in 2015, Latin America suffered substantial losses as a direct result.

While Pink Tide governments certainly delivered populist promises, they did not undertake comprehensive reforms to solve their countries’ problems in the long term. Latin American economies remained unstable.

A mine in Bolivia (Photo: Toniflap / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed])

The Pink Tide and Its Enemies

The initial enthusiasm that ignited the Pink Tide’s ambitions gradually faded. On top of the Great Recession of 2008–2009, falling international commodity prices and intensifying domestic power struggles eventually led to the Pink Tide’s collapse. Right-wing politicians seized the opportunity and took power.

Some argue that the Pink Tide failed because its leaders could not institutionalize progressive policies. Even those on the left criticized conditional cash transfer programs as insufficient to address poverty and inequality. Others accused left governments of succumbing to capitalist pressures in governance, since Pink Tide leaders used capitalist policies to achieve their visions and policies. It should also be noted, however, that leftist leaders had to negotiate policies with various organizations that wielded strong influence over their governments, possessing both internal clout and external connections.

Venezuela is one such case. In 2002, companies opposing Chávez called a general strike. He also faced a coup linked to the U.S. government. Street violence frequently broke out, triggered by clashes between anti- and pro-Chávez camps. Meanwhile, the United States organized a consistent international campaign to isolate Venezuela. In 2019, then-President Donald Trump imposed oil sanctions on Venezuela and recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimately elected leader. In 2024, President Joe Biden reimposed oil sanctions, citing undemocratic actions by the Nicolás Maduro government against opposition leaders.

Leftist leaders also had to remain wary of forcible removals. In 2009, Honduran President José Manuel Zelaya was forced into exile from his residence in an obvious military coup. He returned in 2011 through an agreement with his wealthy successor, President Porfirio Lobo. In 2019, after 14 years in power in Bolivia, President Evo Morales was driven to resign by escalating protests over election results and military pressure. As if exile were not enough, Morales became the target of accusations of statutory rape, human trafficking, and terrorism.

Scenes from the coup in Honduras, 2009 (Photo: rbreve / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Deed])

Parliamentary coups were also effective in ousting Pink Tide presidents. In 2012, Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo was impeached by a right-wing-dominated congress. In Brazil in 2016, President Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s successor, was removed by a congressional vote. For left governments, retaining power becomes the top priority because hostile forces are constantly watching for political openings.

Allegations of corruption, money laundering, and fraud dogged left-wing leaders and tarnished the Pink Tide’s achievements. In 2017, Lula was convicted of corruption and money laundering.

He was implicated in the highly controversial anti-corruption probe “Operation Car Wash.” It was the largest corruption scandal in history, involving two Brazilian giants—Petrobras (the state oil company) and Odebrecht (a construction firm)—and politicians across Latin America. Peru’s President Ollanta Humala and his wife were also questioned in connection with the case.

Peru’s former president Alan García, who was alleged to have accepted bribes from Odebrecht, committed suicide with a handgun before being arrested.

Corruption scandals continued to pour out of the Pink Tide. In 2018, Guatemalan President Álvaro Colom was indicted on corruption charges related to a $35 million contract to procure public buses. Two years later, Ecuador’s exiled Rafael Correa was charged with corruption. Opponents also relentlessly pursued former Pink Tide president of El Salvador Salvador Sánchez Cerén, charging him with illicit enrichment and money laundering involving $351 million in public funds. Mauricio Funes received a 14-year prison sentence for secret negotiations with criminal groups and was handed a further six-year sentence for tax evasion.

Meanwhile, Argentina’s Fernández de Kirchner received a conviction for a crooked deal that awarded government projects to an associate. Costa Rica’s Luis Guillermo Solís received a conviction in 2023 for a crooked deal that awarded Costa Rican government projects to his allies. This series of corruption scandals brought the Pink Tide to an end. Latin America shifted to the right: Mauricio Macri took office in Argentina in 2015, Sebastián Piñera in Chile in 2018, and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

A New Pink Tide

As a harbinger of change in Latin American politics, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of the region and of right-wing political dominance. One report puts COVID-related deaths in Latin America at about 1.6 million—28% of total global deaths. The death toll has been attributed to the region’s “staggering inequality.” The tragic experience of the pandemic, combined with mounting economic pressures to overcome it, revived the political left’s agenda.

The Pink Tide re-entered popular conversation. In 2019, the Supreme Court overturned Lula’s corruption conviction. After 580 days in prison, this allowed him to walk free and seek re-election in 2022. Following Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, and Peru, he joined the roster of sitting left-wing presidents in Latin America. Could the new Pink Tide deliver on its promises? The world watched.

Since 2000, the landscape in Latin America has changed dramatically. The commodities boom slowed and China’s economy decelerated, while U.S.–China geopolitical rivalry intensified, entangling Pink Tide leaders in Latin America due to their close ties with China. Whereas they had pursued a strategy of hedging—cooperating with both competing powers—the increasingly aggressive U.S. foreign policy has caused fresh unease among these governments. The United States has a history of destabilizing and toppling left-wing governments in Latin America, including the regimes of Jacobo Árbenz (Guatemala, 1954), João Goulart (Brazil, 1964), Juan Bosch (Dominican Republic, 1963), Salvador Allende (Chile, 1973), and the Sandinistas (Nicaragua, 1980s), among other examples.

More recently, the U.S. government has been accused of being a factor in the attempted coup in Venezuela and the overthrow of Honduras’s Zelaya. The United States has also imposed economic sanctions on Venezuela and Nicaragua.

At the regional level, the Pink Tide’s ideological diversity has become increasingly pronounced among leaders of all generations. For pragmatic reasons, the new Pink Tide leaders place less emphasis on regional solidarity than their predecessors did. Intra-regional trade has declined, while external trade—especially with China—has increased. Moreover, younger Pink Tide leaders do not hesitate to criticize their fellow leftist leaders. In 2023, Chile’s President Gabriel Boric condemned Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega’s actions against opposition leaders and called him a dictator. Meanwhile, Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico offered asylum to Nicaraguan dissidents stripped of their citizenship. At year’s end, Nicaragua formally withdrew from the Organization of American States (OAS).

The region’s new political and economic context is likely to bring changes in leadership styles and more pragmatic policy orientations. The rifts among Pink Tide leaders may continue to widen.

Brazil’s President Lula da Silva and Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro (Photo: MMA / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Deed])

Domestic Challenges

At the domestic level, the new Pink Tide leaders operate in more polarized societies. Compared with the earlier Pink Tide leaders who enjoyed widespread popular support, today’s leaders face a sizable portion of the citizenry that clearly opposes them. Even the popular Lula won by only a slim margin, 50.8% to 49.2%, over Bolsonaro.

Peru shows the tenuousness of support for the new Pink Tide leaders. In the 2021 presidential election, leftist Pedro Castillo defeated right-wing rival Keiko Fujimori by just 44,000 votes. The following year, Castillo was impeached and detained on rebellion charges after attempting to dissolve the right-wing-dominated congress and install an “exceptional government” government. Vice President Dina Boluarte assumed the presidency but later aligned with the right-wing opposition. Protests against her government escalated as she failed to keep her promises of gradual reform and a transitional government. Under her command, Peruvian authorities responded with force, and at least 60 protesters were killed.

In Chile, the Boric government suffered a defeat when the opposition won 22 of 50 seats on the committee tasked with rewriting the Pinochet-era neoliberal constitution. The right’s victory effectively denied the left parties a veto in the constitutional drafting process. However, voters rejected constitutional drafts from both left and right, and President Boric’s pursuit of a new constitution stalled. Boric’s case shows that public support for initiatives by the new Pink Tide leaders is limited compared to what the earlier Pink Tide enjoyed.

Furthermore, the new Pink Tide leaders are struggling to maintain party discipline. Just a few months after Xiomara Castro was elected president of Honduras, some members of her party broke ranks in congress and allied with the opposition. They openly challenged Castro’s choice for congressional leadership.

A few years into their terms, supporters of the new Pink Tide leaders are also showing signs of disillusionment. President Luis Arce’s platform of “Rebuilding Bolivia United” has come under question as his government pursued the opposition by arresting former interim President Jeanine Áñez and her associates. Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro has been embroiled in corruption controversies involving his family and his former chief of staff.

The weakness of left leaders’ influence over their parties and supporters, falling popularity, and corruption allegations are likely to end the new Pink Tide. On top of that, experts note that anti-incumbentism has taken root in Latin America, as the numbers show: since 2015, in 31 presidential elections, the incumbent party has won only five times. In May 2024, Panama elected right-wing José Raúl Mulino. Whoever the incumbent is, it seems almost inevitable they will lose the next election.

In closing

For ordinary people in Latin America, what matters is their lives—regardless of who holds power. Given the international, regional, and domestic context, the new Pink Tide leaders need to prepare for gathering storms. In the end, despite the new label, the agenda they hoist looks uncannily similar to the promises the first Pink Tide failed to fulfill.

※1 Neoliberalism: an economic policy stance that reduces government intervention in markets, deregulates, and emphasizes the outcomes of free market competition.

Writer: Darren Mangado

Translation: Kyoka Wada

Graphics: Ayane Ishida, Yudai Sekiguchi, Ayaka Takeuchi

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks