In April 2024, Iran drew worldwide attention during a month-long standoff with Israel. The two countries stood on the brink of full-scale war. The chain of events began when Israel bombed the Iranian consulate in Damascus, Syria, on April 1. On April 13, Iran retaliated by using missiles and drones to attack multiple targets in Israel, and further retaliatory airstrikes from Israel followed. Tensions between the two countries then appeared to subside, but if the conflict were to expand, it could not only further complicate the situation in the Middle East, it could also draw Israel’s allies—especially the United States—into the conflict. The outcomes of such a complex conflict would be harder to predict and could bring more dangerous geopolitical and economic consequences, potentially affecting a wider part of the world.

Some suggested that Iran’s retaliatory attack was calibrated to minimize damage to Israel. Given the effects of decades of international economic and military sanctions, it is only natural that Iran’s leadership would not want an all-out war with a far more powerful enemy. However, Iran’s retaliation tactics seemed to carry a message aimed less at the world than at the Iranian public. That messaging was strikingly evident in Iranian media after the incursion into Israeli territory. Although the attack caused very limited damage in Israel, political and military leaders seized every opportunity to tout the success of the retaliation and dominate the media narrative.

This propaganda campaign, and the government’s broader intent to present itself as a militarily strong country, offers a glimpse of one of the leadership’s most serious concerns. That concern is reflected in a series of protests in recent years and signals that Iranians have begun to question the government’s legitimacy. The Iranian government has long relied heavily on religious ideology for its legitimacy, but in recent years the public has grown dissatisfied with economic conditions, political repression, and the widening gap between the government’s rhetoric and lived reality. When trigger events sparked protests, these factors helped rapidly draw in broader crowds and amplify their impact.

Such recent social unrest has produced a crisis of legitimacy that threatens the foundations of the Iranian regime. This article offers an overview of that crisis of legitimacy, focusing on some of the disturbances noted above.

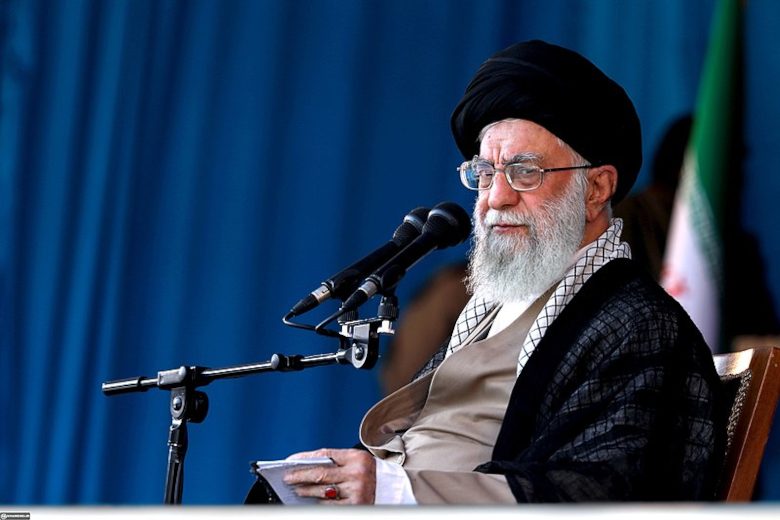

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei (Photo: Khamenei.ir / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0 Deed])

目次

Early roots of the unrest

The roots of the current Iranian regime’s legitimacy problem can be traced back to 1979. Under the leadership of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran toppled the Pahlavi dynasty that year, ended a monarchy that had lasted more than 2,000 years, and established an Islamic Republic. From its infancy, the newly born regime harshly criticized its predecessor and pursued an assertive anti-Western foreign policy grounded in revolutionary ideals. Shiite clergy, empowered as never before, exerted direct influence and strictly implemented authoritarian civil laws.

Just a year after the revolution, in 1980, Iran was engulfed in a brutal war with neighboring Iraq. As a Shiite-majority state established in a region dominated by Sunni-led countries, Iran further strengthened the ideological foundations of the regime. After eight years of war, Iran experienced a degree of prosperity driven by massive crude oil exports. At the same time, leaders were scheming over the geopolitical project of exporting the Shiite revolution to other countries in the region.

However, this relatively brief period of prosperity ended when a secret program to obtain uranium enrichment know-how was made public in 2002. The successive waves of severe economic sanctions against the program not only isolated the regime internationally but also dealt a heavy economic blow to the country’s new industries, rendering the promise of prosperity largely hollow. Western countries’ demands for political and social reforms also increased, but Iran hardened its conservative political posture. These developments snuffed out hopes that society might gradually become more open.

Beneath Iran’s current dire situation lies a gradual erosion of legitimacy. Even among people who might have supported the regime decades ago, that legitimacy is fading. In recent years, the government’s predicament has become more severe than ever. To understand the causes of this legitimacy crisis, it is important to delve into the recent historical background. Doing so clarifies how recent social movements developed into large-scale anti-government demonstrations.

The flames of economic discontent

A key factor that shaped Iran’s domestic and foreign policy in recent years was the 2015 agreement between Iran and the UN Security Council’s permanent members (the United States, the United Kingdom, China, France, and Russia) plus Germany over Iran’s nuclear program. Under this agreement, Iran halted nuclear activities and sanctions imposed by the UN and other major powers were lifted.For Iran, which had been isolated for nearly a decade, this marked the beginning of a new era, and the country began re-entering global markets. However, contrary to the initial optimism, U.S. economic sanctions were reimposed in 2018 by then–U.S. President Donald Trump.

A year after the sanctions were reimposed, in November 2019, Iran’s currency suffered a staggering 400 percent plunge. Furthermore, to plug a budget deficit worsened by the financial morass, the government decided to triple fuel prices. Those most affected by this sudden decision were low-income people already struggling under the sanctions, while unemployment and bankruptcies rose across the country.

Anger toward the government over the fuel price hike, combined with prior economic hardship, triggered the largest protests since the Islamic Revolution. Tens of thousands of ordinary Iranians took to the streets. Economic pressure, more than social or political grievances, was the main driving force. The regime soon cut off the country’s internet connection, making it almost impossible for international media to cover the uprising. During this period, government forces—especially the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—reportedly killed more than 1,500 people and arrested thousands more.

Many people have fallen victim to the regime’s repression throughout the 40 years of the Islamic Republic, but the scale of bloodshed during the November–December 2019 demonstrations was of a different nature. In earlier cases, government forces generally avoided firing directly on protesters and tried to suppress them using other hardline measures. What was notable in this round of violence was its resemblance to the methods of the former monarch. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last shah, responded with similar violence to protests that led up to the 1979 revolution. After the revolution, the new regime frequently expressed sympathy for those killed during the uprising and condemned the previous regime as “illegitimate” for killing civilians. Yet for many Iranians who still vividly remember the events of the revolution, these protests and the regime’s response brought those memories back. In the eyes of many Iranians, a regime that fires on demonstrators and kills Iranians has already forfeited its legitimacy.

Events marking the anniversary of the Iranian Revolution (Photo: Meghdad Madadi / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0 Deed])

The assassination of Qassem Soleimani and its aftermath

The Trump administration’s abandonment of the Iran deal can be seen as having spawned various confrontations between Iran and the United States. In 2020, however, the conflict escalated to a different level when Iranian military officer Major General Qassem Soleimani of the IRGC was assassinated by a drone in Iraq on the direct order of then-President Trump. The incident and its aftermath also affected relations between Iran’s political leadership and a public already on edge.

Soleimani was one of the most popular public figures in Iran. His assassination aligned with the regime’s image of America that it has continuously projected since its inception: the image that “America is the murderer of a national hero, the absolute evil, and the country’s greatest enemy.” For the Iranian regime, the assassination provided an excellent opportunity to lift public opinion from criticism of its handling of the 2019 unrest to unity against a common external enemy.

The regime made the most of this tragic event, organizing memorials across the country to stoke anger toward the United States. Millions attended these ceremonies, which were saturated with religious and anti-Western symbolism and were portrayed as proof of the regime’s popularity among Iranians. For a brief moment, it seemed the regime had managed to erase the unfortunate memory of the 2019 protests. As revenge for the general’s assassination, the IRGC launched dozens of missiles at a U.S. base in Iraq (Al Asad Air Base) on January 8, 2020. To minimize casualties, the IRGC warned the Iraqi president about the attack five hours in advance. By reducing casualties, the regime could deter U.S. retaliation while still announcing victory over America to the public.

However, just hours after the missile launches, the IRGC mistakenly shot down a passenger plane bound for Ukraine a few kilometers south of Tehran, apparently misidentifying it as an American missile. All crew and passengers on board were killed.Both IRGC leaders and the Iranian government initially denied responsibility for the incident. The day after the crash, senior government officials went on state television and claimed the plane had crashed due to a technical problem. Soon, however, undeniable information was released internationally, and the government was forced to acknowledge its error. An IRGC commander appeared on state television to explain that the IRGC had shot down the plane and would take full responsibility.

In response, protests broke out in Tehran on January 11, 2020, and spread to several other cities. Demonstrators condemned the missile strike and the subsequent cover-up by Iranian authorities and demanded the resignation of Supreme Leader Khamenei。

Protests over the downing of the passenger plane (Photo: Mohsen Abolghasem, MojNews / Flickr [CC BY 4.0 Deed])

The significance of this incident lies in how it evoked vivid memories that shocked millions of Iranians. It resembled one of the most direct acts of violence the United States has committed against the Iranian people. In 1988, two surface-to-air missiles fired by the U.S. Navy’s guided missile cruiser Vincennes shot down an Iranian passenger plane over the Persian Gulf in Iranian airspace. The U.S. claimed it was an accident, but Iranian politicians kept the incident alive in the public memory for years. In the 2020 shootdown, the IRGC did what Iranians regard their greatest enemy as having done: it killed innocent people, denied responsibility, and tried to deceive millions.

This incident not only newly highlighted the problems facing Iran’s leadership; it also led many Iranians who were not necessarily anti-regime—and even traditional supporters of the regime—to begin questioning the Islamic government’s legitimacy. The missile strike on the U.S. base in Iraq, part of an attempt to bolster domestic support, not only failed but further underscored the rift between the public and the regime.

The water crisis in Khuzestan Province

Soon after these crises, new economic problems began to emerge. Iran has abundant oil resources, but most are in the south of the country, particularly in Khuzestan Province. Despite its oil wealth, Khuzestan has lacked basic infrastructure and remained poor. This led to new social unrest.

In the summer of 2021, a wave of protests began in Khuzestan and later spread nationwide. The main cause was water shortages. Khuzestan is Iran’s hottest province, with summer temperatures reaching 40°C. That year again brought a scorching summer. Repeated heatwaves and shrinking marshlands, combined with numerous dam constructions along the province’s rivers, put enormous pressure on residents, resulting in water shortages and protests against the Iranian government’s water management policies .

Oil fields in Khuzestan Province (Photo: youngrobv / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed])

The protests initially began over concerns about water management but quickly developed into a broader anti-government movement. Demonstrators chanted “Death to the dictator,” referring to Supreme Leader Khamenei. Security forces intervened and opened fire on protesters, causing many injuries and deaths. On social media, many users showed solidarity with protestors using hashtags such as “What have you done to water?” (#ب را چه کردید) and “Khuzestan is not alone” (#خوزستان تنها نیست).

The significance of these protests lies in their symbolism. For Shiite Muslims and their identity, water and access to water carry deep meaning. In the 600s, the third Shiite Imam, Imam Hussein, was killed along with close family and companions after being denied water. Every year, Shiites around the world commemorate this historical event. In Shiite culture and identity, refusing water to anyone is considered unacceptable, regardless of region or ethnicity. Yet the Iranian government, which prides itself on being the leader of the world’s Shiites, failed to provide this basic yet fundamentally important right to its people, highlighting the growing dissatisfaction among Iranians and the contradiction in the government’s claim to religious leadership.

The struggle for women’s rights and social change

Iran is known for extremely strict laws regarding women, who must cover not only their bodies but also their hair in public. The compulsory hijab (women’s dress code) is enforced through the Guidance Patrol (morality police). The Guidance Patrol patrols cities, stopping and arresting people who violate the national dress code. Although it is ostensibly supposed to monitor both men and women, in practice it has become a tool of the regime to target, control, and restrict women, significantly impeding women’s freedom of movement.

Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979 and the enforcement of such strict laws concerning women, Iranian women have lived under these harsh rules. Many have protested and demanded reforms. Despite extremely strict restrictions on women’s freedom, a powerful movement of Iranian women calling for equality and fundamental human rights has persisted. One of the most striking examples is the recent civil unrest against the violent enforcement of the aforementioned coercive dress laws.

Guidance Patrol instructing women (Photo: Ebrahim Noroozi / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0 Deed])

On September 13, 2022, a young Kurdish woman named Mahsa (Jina) Amini was detained by the Guidance Patrol in Tehran, where she was visiting from her hometown of Saqqez, on suspicion of violating Iran’s compulsory hijab rules by wearing it only partially. She reportedly suffered severe physical abuse at the hands of patrol officers, which Iranian authorities denied. After the incident, she collapsed and was taken to a hospital, where she died three days later 。

Her death in custody sparked protests across the country. The main slogan was “Women, Life, Freedom” (in Persian: زن، زندگی آزا. In Kurdish: ژن ، ↪، ئازادی,: Jin、Jiyan、Azadî). The slogan expresses the idea that women’s rights are fundamental to both human life and freedom. Originating in a women’s march within the Kurdish freedom movement in Turkey in 2006, the slogan echoes the philosophy of Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan—the claim that “so long as women are not liberated, true freedom of the nation cannot be achieved.”

What began as peaceful demonstrations soon developed into full-fledged social unrest, disrupting daily life in nearly every province. It was clear that other issues were also fueling the protests. In other words, Mahsa (Jina) Amini’s death was not simply the loss of an innocent life, nor were the protests limited to the issue of women’s rights. They also symbolized the culmination of the grievances and frustrations that ordinary Iranians held toward a regime that had failed both economically and politically.

As social protests continued at home, the government responded with heavy-handed methods. At least 551 people, including 68 minors, were reportedly killed by the government. A 9-year-old boy was also shot dead during the government’s crackdown on protesters.

A temporary reprieve from economic and social turmoil

In the years since sanctions were reimposed, Iran’s economic situation has further deteriorated. When the movement began in 2022, the exchange rate for 1 U.S. dollar was 30,000 rials. In just two years, it rose by 200 percent to nearly 60,000 rials in 2024 . Regardless of the underlying reasons, what matters is that this has had a devastating impact on Iranians’ daily lives. For a country unable to export its largest commodity, oil, to the fullest due to U.S. sanctions, this currency depreciation only worsens economic hardship.

Over time, the number of protests gradually decreased, and the government scaled back Guidance Patrol activities. Online, videos circulated showing women walking through Iranian cities without scarves. This newfound social freedom did not directly change the laws, and going without a scarf remained illegal, but it was nevertheless a step back for the government. Simply walking down the street without a headscarf—still illegal in law—became something seen among many Iranian women.

However, about two years after the government’s response began to loosen, things gradually started to change. In April 2024, Supreme Leader Khamenei addressed this newly visible women’s freedom in one of his speeches. Contrasting it with the values upheld by the Iranian government, he signaled a tougher stance against women who do not comply with the national dress code. As a result, large numbers of women who did not follow the dress code began to be arrested.

Missiles on display at the anniversary of the Iranian Revolution (Photo: Mahdi Marizad / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0 Deed])

Given the dire economic situation, ongoing social protests, and government repression, there is concern that unrest could escalate. Israel’s attack on Iran’s embassy in Syria further exposed Iran’s external vulnerabilities. Iran is already facing a crisis of legitimacy. In a country where many citizens seek to topple the regime, such an attack on national soil posed a major threat.

Therefore, it was not only to retaliate against Israel’s actions, but perhaps more importantly to heighten nationalist sentiment, that the regime chose to flaunt its military might. The message to Iranians was: “No matter how dire the economy or how minimal social freedoms may be, when faced with enemy attacks, it is the government and its military that will fight to protect people’s lives.”

Whether this display of military power will restore the legitimacy that the Iranian government has long lost remains to be seen. But it certainly affirmed the image of a government standing strong in the face of external threats. Many economic and social challenges continue to affect many people’s lives, and only time will tell how long this calm will last.

Writer: Tahereh Mohammadi

Translator: Kyoka Wada

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

イラン情勢についてとても分かりやすく書かれていました。中東の歴史や現状は何度理解しようとしても、複雑で難しいので、こちらの記事だけではなくほかの記事も読んでみたいと思いました。