Artificial intelligence (AI) has made remarkable progress and is now being used in all sorts of everyday situations. As AI comes to be used in various aspects of life and industry, both expectations and anxieties are growing over how society will change. Needless to say, AI is convenient, but gaps may emerge between those who can make use of AI and those who cannot, or between those who can use AI to enrich their work and activities and those who cannot. Pushed further, there will also be disparities between those who can access AI and those who cannot, those who can access the internet and those who cannot, and those who can access computers and those who cannot. In other words, some people around the world can enjoy the convenience of AI, but others lack educational opportunities to utilize it, and others still lack access to the infrastructure—such as the internet and computers—commonly used to run AI. As a result, debates have arisen over whether AI can be a factor that corrects disparities or, conversely, expands them.

As shown by the figure that half of the world’s wealth is owned byjust 26 people, it is hard to say that global inequality is improving. In 2020,97 million people newly fell into poverty, and in April 2023, as the United Nationssounded the alarm that the number of people in extreme poverty had increased compared to four years earlier, what role will AI play and how will it affect the world? Let us consider the use of AI from the perspective of reducing poverty and inequality.

ChatGPT app (Photo: Focal Foto / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed])

目次

The current state of global inequality

The world’s five richest people have continued to increase theirassets by 14 million US dollars per hour, while since 2020, poverty has worsened for 5 billion people worldwide. Inequality and the poverty that stems from it are known to have direct impacts on people’s lives and livelihoods. Ifincome is higher, people tend to live longer, child and maternal mortality declines, the quality of health care improves, and access to infrastructure such as safe water and electricity is more likely to be ensured. Moreover, higher incomealso affects quality of life by making it easier to obtain better education and outcomes, and by allowing more time for travel and leisure.

There are many causes of inequality, but the international NGOOxfam focuses on corporate factors, listing six causes: (1) companies oppose laws and labor regulations that benefit workers, such as raising minimum wages; (2) beginning with privatization, private enterprises exacerbate racial and gender disparities; (3) companies are not structured democratically, with billionaires serving as major shareholders of the world’s top firms; (4) effective corporate tax rates have fallen to one-third of their levels over the past decades, and most large corporations pay little to no tax; (5) monopolies enable a small number of companies to greatly influence people’s lives; and (6) the current economic system is creating a new colonialism, with middle- and low-income countries facing massive debt repayments.

Inequality is not caused by corporations alone. In terms of problems within the economic system, a tendency to exacerbate disparities was clearly evident during the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) 2021 allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). SDRs are avirtual currency distributed to IMF member countries that can be used to draw foreign currency in the event of an economic crisis and a shortage of foreign exchange. The IMFargues that by leveraging this system it can provide liquidity support to low-income countries, enabling them to pay for things like health care. In 2021, concerned about global economic trends, the IMF allocated the largest amount ever,equivalent to 650 billion US dollars. While EU member states received about 160 billion dollars, African countries—home to roughly three times the EU’s population—received only34 billion US dollars. The UN Secretary-Generalsharply criticized the current situation in which even virtual currencies like SDRs are preferentially allocated to high-income countries, stating that “the rules and governance of the system that produce such outcomes are fundamentally wrong.” However, this is only a small part of the structural problems underlying today’s inequality; the structure of the global economy, governance issues, and more are intricately intertwined in producing disparities.

“Technology for all” — a presentation at a conference on AI (Photo: ITU Pictures / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Deed])

The impacts of economic inequality also relate to essential modern infrastructure such as internet access. Many middle- and low-income countries possess highly developed technologies in fields like electronic transfers. For example, inCentral Asian countries, where digitalization has rapidly advanced in recent years, the level of digitalization in areas such as the economy is said to be comparable to that of high-income countries. Moreover, while mobile money transfers account for 5% of GDP on average globally, in Africa they average25% of GDP, making it a region where digitalization in the financial sector progressed early.

On the other hand, only about35% of the population in middle- and low-income countries has internet access, a large gap compared to 80% in high-income countries. If internet connectivity in middle- and low-income countries could be raised to75% of the population, it is estimated that these countries’ combined GDP would increase by2 trillion US dollars and 140 million jobs would be created. As internet access is tied to socioeconomic human rights, and as access to the internet itself is increasingly seen as ahuman right, inequality viewed through the lens of internet connectivity will be an important perspective for future global trends.

The current state of AI use in low-income countries

Being able to connect to the internet brings many benefits beyond simply increasing access to information. One of these is the use of AI. AI generally refers toinformation processing technologies that humans consider intelligent, including machine learning and deep learning. While machine learning refers to enabling a computer to acquire patterns from input information, in deep learning thecomputer can discover for itself the features needed to effectively distinguish characteristics of the input information. This overall flow of feeding information to computers, having them process it, and make judgments is broadly referred to as AI.

In the process of feeding information to computers and training them, it is common to leverage the vast information available on the internet, and many services using AI today are built onfoundation models (FMs) that have been pre-trained on massive datasets. However, even when using these foundation models, specializing them through a process called fine-tuning is necessary to handle more complex tasks. Moreover, analyzing real-time data such as weather and traffic information, and continuously updating data, typically relies on the internet; thus, internet connectivity and AI utilization are closely connected.

Data center (Photo: Rawpixel[CC0 1.0 Deed]

AI is increasingly used in various contexts, but how is it being used to reduce inequality in low-income countries?

For example, as a poverty-alleviation case, there arecash transfers in Togo. In this project, the nonprofit GiveDirectly worked with the Togolese government toidentify areas of severe poverty using satellite imagery, and targeted people in extreme poverty by analyzing mobile phone data with machine learning. By assessing contactability by phone, they provided cash transfers toover 130,000 people. With the involvement of government and researchers and by using machine learning methods, they were able to transfer to an additional4,000 to 8,000 people who might otherwise have been excluded.

AI use in agriculture is also remarkable. By developing machine learning techniques using large-scale soil samples and satellite imagery, there are methods that consolidate information across soil, climate, seasonal conditions, and more, enabling year-roundsoil measurement. This technology, which can measure land characteristics with a resolution of 100 square meters, is used for soil monitoring and in regenerative agriculture, and has been introduced in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay in South America. Furthermore, AI is used worldwide to protect crops from disease and to respond when they do occur. In Vietnam, for example, AI is used in anapp service that identifies crop diseases, supports healthy growth, and connects farmers with agricultural experts. By leveraging AI, the service canquickly diagnose diseases from images of plants. A systemspecialized in banana diseases has achieved results in West Africa and southern India. By effectively using these technologies, farmers can expect to reduce production losses, which may lead to higher incomes.

Detecting plant diseases with a smartphone app (Photo: CGIAR System Organization / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Deed])

AI adoption is also advancing in education. For example, in higher education inLatin American countries, there are initiatives to support students using AI. In somecases, factors affecting academic performance are identified with AI, and chatbots are introduced for student mental health support so that more students can receive assistance. There are similar examples elsewhere; onetechnology widely used particularly in South Asia aims to improve the quality of education by having AI chatbots support learning tailored to individuals. At the same time, someviews argue that access to AI-enabled education is limited to certain groups, and that efforts should focus on using AI to support teachers’ roles and make education more inclusive.

Will the use of AI reduce global inequality?

In conclusion, it cannot currently be stated definitively that it will either reduce or widen inequality. As the various cases show, using AI can likely deliver pinpoint support to those who need it and improve the quality of public services. However, we cannot say for sure that AI will contribute to correcting the inequalities the world currently faces.

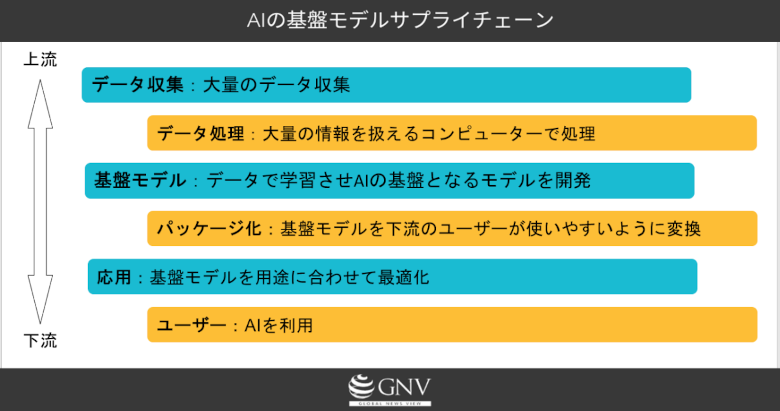

Thefoundation model supply chain vividly illustrates the structural inequalities AI carries. Upstream in the foundation model supply chain are processes such as collecting data, and designing and training the model; downstream are processes to optimize AI into forms desired by users so they can use it. Developing foundation models usesdiverse and massive datasets. These data are not simply complete once input; they must be categorized and labeled bymany human hands. Exploitation at that stage has beencriticized. Of course, the need for human labor to categorize and label data also exists downstream in the foundation model supply chain, but far more people are involved in developing foundation models, where the volume of input data is orders of magnitude larger.

Users downstream in the supply chain are, at present, compelled to rely on foundation models created upstream. Developing a foundation model requiresmillions of US dollars and is not something that can be developed casually, so general users will end up using foundation models created upstream in the supply chain. There are various foundation models currently in circulation. Representative examples includeBERT developed by Google;Microsoft has invested billions of dollars in OpenAI, which offersGPT; Amazon’sTitan; Anthropic’sClaude; and Meta’sLLaMA. The upstream of the supply chain is a highlyclosed market monopolized by a small number of companies, and it may become a factor that widens inequality going forward.

Moreover, existing economic disparities may influence the use of foundation models as well. When general users leverage AI, as mentioned above, it is difficult to develop from the ground up, so it is common to use a foundation model and perform fine-tuning to obtain the desired performance. For example, suppose GNV wants to introduce a chatbot to its website. A low-cost approach would be to use a foundation model as the base and input GNV-specific information, so it can function as GNV’s chatbot. In this fine-tuning process, one inputstokens, the smallest units of text data, and manypricing schemes vary according to the amount of tokens processed. In other words, users with larger budgets for AI optimization can input more tokens and achieve more accurate predictions. Conversely, users without sufficient funds are limited in how many tokens they can input and cannot attain high-accuracy predictions.

One might even argue that the very structure in which AI technology is developed accelerates inequality. At present, even if one speaks of using AI, as noted above, one is effectively forced to rely on a small number of private companies in high-income countries. ChatGPT has already begun offering prioritized server access for 20 US dollars per month, and for people in low-income countries with lower average incomes, such paywalled services canbecome a barrier to using AI. If such trends spread, disparities between workers who can use AI to improve their efficiency and those who cannot will surface in ways that reflect existing economic gaps.

Toward closing the AI divide

Someargue that to prevent the development and expansion of AI use from widening existing gaps, low-income countries should begin early with digital skills education and cultivate a workforce that can use AI. While highlightingexamples such as Kenya’s efforts to improve information and communications technology (ICT) skills from the early childhood stage, the observation also notes that many low-income countries are still at the initial policy-implementation stage when it comes to incorporating digital skills into education.

Students using a computer at a school in Tanzania (Photo: ROMAN ODINTSOV / Pexels [Pexels License])

On the other hand, someresearch findings hold that inequality is determined less by how individuals work and what talents and skills they possess than by factors individuals cannot choose—where they are born and the economic situation of their birthplace/country. And it argues that closing gaps arising from birthplace and country is difficult to achievewithout redistribution.

The cost of establishing broadband internet access in every country on the African continent is estimated at100 billion US dollars. This may seem like a large amount. However, enabling more people to use the internet is known to produce good economic outcomes. In middle- and low-income countries, a 10% increase in internet penetration alone raises GDP growth by1.38%. The overall economic impact that AI is expected to generate by 2030 is said to reach15.7 trillion US dollars. By pursuing initiatives that allow middle- and low-income countries to benefit from these economic gains, narrowing inequality may become a reality.

Who, and where, will the 15.7 trillion US dollars in economic value generated by AI enrich?

Writer: Azusa Iwane

0 Comments