About 1.4 billion people live in China, a major power. In 2023 its gross domestic product (GDP) was about US$18 trillion, making it the world’s second-largest economy after the United States. Geographically close to Japan and strongly connected in trade, it also faces major confrontations in terms of history and security, drawing significant attention in Japanese media.

So, what tendencies does that coverage exhibit? Here, we analyze those trends.

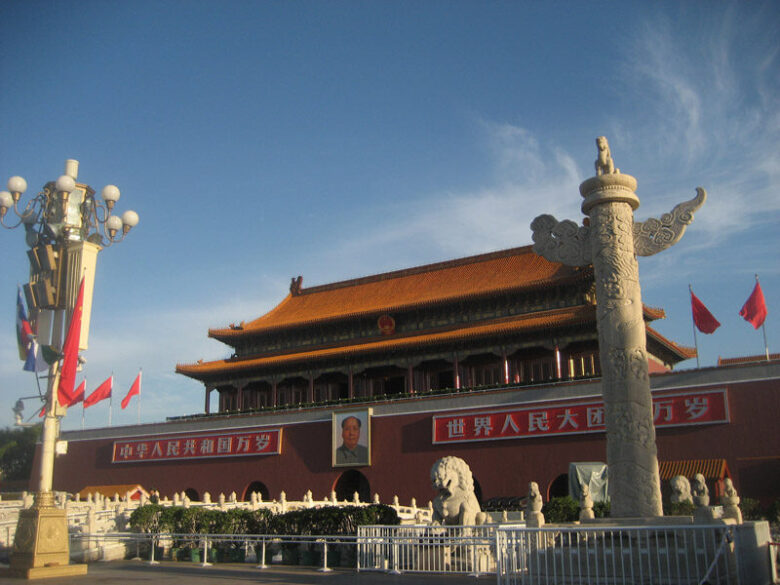

Tiananmen Square (Photo: jiejun tan / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Basic information about China

First, let’s briefly review China’s modern history with a focus on governance. In 1911, the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) established the Republic of China, the country’s first republic. However, warlordism and the Japanese invasion kept the situation unstable, and large-scale armed conflict also broke out with the Communist Party led by Mao Zedong. After winning this conflict, the Communist Party established the People’s Republic of China in Beijing in 1949, shifting the economic system from capitalism to socialism, and in 1951 formally annexed Tibet to China under the Seventeen-Point Agreement. Meanwhile, the ROC government relocated to Taiwan. This resulted in two governments claiming to represent China, yet the ROC continued to hold China’s seat at the United Nations. However, in 1971 a majority vote of the UN General Assembly transferred the UN seat to the PRC.

In 1978, Deng Xiaoping introduced market reforms, transitioning to a socialist market economy. This spurred rapid economic growth but also widened the wealth gap. In 1997, under the Sino–British Joint Declaration, Hong Kong—until then a British colony—was returned to China. Since 2022, China has stepped up military exercises around Taiwan, and confrontation with the ROC government in Taiwan appears to be ongoing.

Next, the country’s ethnic groups and languages. China is a multiethnic state in which 56 groups coexist, and more than 300 languages are used. The most widely used is Chinese (Sinitic), but there is diversity within Chinese itself, and it is often said that the differences in grammar and pronunciation between Standard Chinese and regional dialects can be on the level of separate languages.

Now to present-day realities in China. Economically, the country has achieved rapid growth, and one consequence has been notable progress in lifting people out of poverty. According to World Bank data, China’s overall poverty rate (Note 1) fell dramatically from 66.6% in 1990 to 1.9% in 2013, a major decline. On the other hand, many people today appear to be facing difficult conditions due to a property slump and falling stock market. In business, the information technology (IT) sector has developed remarkably, and in 2023 mobile payment penetration reached 86%, the highest in the world. Recently, groundbreaking IT services such as fresh-food e-commerce have also emerged. At the same time, it is said that the government has strengthened systems to monitor citizens alongside the advance of IT.

China’s leading mobile payment services WeChat and Alipay (Photo: John Pasden / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

In terms of human rights, there are issues of censorship, such as critics of the authorities being detained and the media being controlled by the government. While such human rights problems are seen nationwide, there are regions where repression is particularly severe. In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, there are allegations (Note 2) of unjust repression, including the mass detention of Uyghurs.

In foreign affairs, China has territorial disputes with Japan, the Philippines, and India, and since 2018 it has been in sharp confrontation with the United States over trade and security. At the same time, it has rapidly increased lending and assistance to low-income countries in recent years.

Understanding China through the volume of coverage

As noted, China has many facets, but how is it reported in Japan? Let’s first infer trends from the volume of coverage. We analyzed reporting in the Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri newspapers from 2015 to 2022 (Note 3).

The analysis shows that China is covered extensively and consistently each year in Japan. As the graph below indicates, the combined annual volume across the three papers from 2015 to 2022 was about 1.2 to 1.3 million characters, corresponding to roughly 1,700 to 1,900 articles. In rankings by country, China usually places second after the United States; however, in 2022, coverage of Russia and Ukraine surged due to the war, pushing China down to fourth. Although its relative ranking fell, the amount of China-related coverage in 2022 was about 1.37 million characters, slightly higher than the previous year.

While China is reported on heavily every year and the topics are diverse, the content shows yearly characteristics. Below is a rough look at the topics that drew the most coverage each year. In 2015, articles focused on the stock-market slump known as the “China shock.” In 2016, the dispute with the Philippines over the Spratly Islands was widely reported. From around 2017–2018, articles on U.S.–China confrontation surged. In 2019, there were many items about the protests in Hong Kong (Note 4) and articles on allegations of repression of Uyghurs. In 2020, COVID-19–related content dominated. In 2021, articles highlighted the escalation of confrontation with the ROC government in Taiwan. In 2022, many reports discussed China’s positioning in the Russia–Ukraine war.

Thus, although China is covered in large volumes each year, the topics reflect events occurring domestically and abroad in each year.

Understanding China through related countries

As noted above, China is often reported in connection with other countries. We therefore analyzed data from 2015 to 2022 to identify which countries are most frequently associated with China, and calculated the top five countries co-mentioned with China.

As shown in the graph below, the top two spots are occupied each year by Japan and the United States. Rough article counts are about 500–1,000 per year for the United States and about 300–500 per year for Japan. Japan ranked first in 2015 and 2016, but from 2017 the surge in U.S.–China confrontation coverage reversed the order, putting the United States in first place. Meanwhile, coverage related to Japan has trended downward in recent years.

Other countries frequently appearing near the top include South Korea, North Korea, and Russia. In 2015, South Korea ranked third with about 135 articles, with extensive reporting on the first Japan–China–ROK trilateral summit in three and a half years. Around 2017–2018, North Korea ranked third with roughly 200–300 articles, as coverage of China easing sanctions on North Korea increased. From 2020, Russia ranked third with about 50–200 articles, often in contexts linking China to U.S.–Russia tensions. In 2022, many articles discussed China in connection with the Russia–Ukraine war. Also within the top 10 were Ukraine, which is linked via war-related coverage; India, a neighboring great power that disputes borders with China; and high-income countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and France.

In examining China’s relations with the world, ties with Taiwan are also a key point, as noted above. While indeed most countries in the world regard Taiwan as part of China and do not recognize it as an independent state, in practice a separate government administers it. When Taiwan is included in this ranking, it typically places between third and fifth.

Thus, although the rankings vary by year, great powers and neighboring countries are most likely to be linked with China in reporting. Conversely, the analysis also shows that there are relatively few articles associating China with countries in the Global South. Among China’s neighboring Global South countries with close ties, Vietnam appeared in roughly 5–10 articles, Myanmar about 5–10 articles, and Pakistan about 1–2 articles. Looking at other regional powers, Brazil had about 2–5 articles, South Africa about 0–2, and Saudi Arabia also about 0–2.

Coverage of China in 2022

Thus far we have analyzed trends from 2015 to 2022, but zooming in on a single year can reveal more detailed patterns. We therefore took a closer look at reporting on China in 2022.

First, the monthly volume of coverage in 2022. As the graph above shows, coverage was relatively heavy in March, May, October, and December. A closer look shows that March featured many articles about the imposition of a lockdown in Shanghai in response to the spread of COVID-19 and about the Russia–Ukraine war. May saw prominent coverage of the UN High Commissioner’s visit to Xinjiang. In October, many items concerned President Xi Jinping’s start of a third term. In December, articles on the policy shift from “zero-COVID” to “with-COVID” were prominent.

Next, the share of coverage by genre. As shown in the graph below, politics accounts for roughly 45%—overwhelmingly the largest. Other categories reported comparatively often are the economy (about 17%), military (about 8%), and society (about 7%). As expected, topics concerning the central government and elites are more likely to be covered. By contrast, there are few articles on science and technology (about 0.8%) or arts and culture (about 0.6%).

A closer look at politics-related coverage: in 2022 there were 774 articles, most of which focused on actors involved in national decision-making such as the central government—670 articles (about 87%). By contrast, there was little coverage centered on ordinary people—16 articles (about 2%)—mainly on protests against government policies or opinion poll results.

A closer look at economy-related coverage: in 2022 there were 287 articles, most concerning the property downturn, stock market declines, macroeconomic data, and corporate moves, while there were none concerning the poor. Elites and the wealthy are readily covered, whereas the poor are not covered at all.

Next, minority-related articles. In 2022, there were 19 articles in which ethnic minorities were the main subject: 13 on Uyghurs, 5 treating minorities in general in abstract terms, and 1 on Tibetans. As noted, 56 ethnic groups coexist in China, but not a single article covered minorities other than Uyghurs and Tibetans. While the prominence of repression against Uyghurs and Tibetans makes them more newsworthy, it is clear that even among minorities some receive extensive coverage while others do not.

Conclusion

With its enormous population and economy, China has many facets across history, politics, the economy, and culture. Coverage of China in Japan is large and steady every year. However, it is skewed: moves by elites such as the central government and the wealthy draw major coverage, while science and technology, arts and culture, and the actions of ordinary people and the poor receive relatively little attention. There is also a bias in the countries with which China is co-reported: relations with great powers and neighbors tend to receive heavy coverage, whereas ties with countries in the Global South tend not to.

To understand China objectively and from multiple angles, it will be important to pay attention as well to aspects that currently receive little or no coverage.

Note 1: The extreme poverty line set by the World Bank in 2015—that is, the share of people living on less than US$1.90 per day.

Note 2: After the 2014 bombing attacks in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Chinese authorities detained people suspected of being terrorists in internment facilities. Since 2019, mainly Western countries have alleged that Uyghurs are being unjustly detained and have raised suspicions of forced labor and genocide within the facilities, alleging as much.

Note 3: The analysis aggregates only the morning editions of the Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri newspapers.

Note 4: In 2019, large demonstrations broke out in Hong Kong against a proposed amendment to the extradition ordinance that would have enabled the transfer of suspects to mainland China. The bill was withdrawn in response to the protests, but in 2020 the Hong Kong National Security Law, which prohibits acts such as subversion of the state, was enacted.

Writer: Koki Usami

中国の報道が多く、内容に偏りがあることは感覚的に分かっていますが、この記事のように分析した数字があると良いですね!

日本の中国報道は、ほんとに悪い面しか切り取ってないなという風に感じます