Norway has implemented many climate change measures. For example, Norway covers almost all of its electricity with renewable energy, and in 2020, renewables accounted for 98% of electricity generation, of which hydropower made up 92%. Norway also has the world’s highest per-capita use of electric vehicles, and 42.4% of cars sold in 2019 were electric.

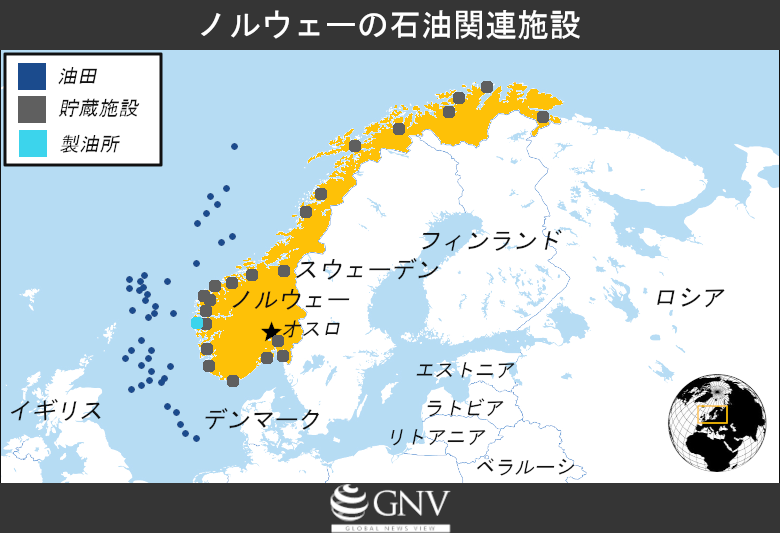

On the other hand, Norway is highly dependent on the oil and gas industry. In 2021, Norway ranked 11th in oil production and 9th in natural gas production globally. The oil and gas industry accounts for 14% of Norway’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 40% of exports, and in 2023 Norway supplied 44.3% of the European Union’s (EU) natural gas imports. About 200,000 people work in the oil and gas industry, accounting for over 5% of all workers.

This article first outlines the history of the development of Norway’s oil industry and then explores how Norway will address the contradiction of being proactive on climate action while remaining dependent on the oil industry.

A Norwegian oil platform in the North Sea (Photo: Jan-Rune Smenes Reite / Pexels [Legal Simplicity])

目次

History of Norway’s oil extraction

After a gas field was discovered in Groningen, the Netherlands, in 1959, it came to be believed that oil fields might exist in the North Sea as well. Accordingly, in 1962, the American petrochemical company Phillips Petroleum submitted an application to Norwegian authorities seeking permission to conduct geological surveys on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS). Given the potential for petroleum deposits on the NCS, in May 1963 the Norwegian government declared sovereignty over the NCS. Under Articles 77(1) and (2) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a coastal state has exclusive rights to explore and exploit natural resources on its continental shelf. With the declaration of sovereignty over the NCS, all natural resources on the NCS became state property, and only the government held the authority to grant exploration and production licenses. Since then, the Norwegian government has negotiated the rights to the NCS with individual companies.

The first licensing round (※1) was held in 1965, and 22 production licenses were awarded to multiple oil companies covering all 78 blocks into which the continental shelf had been divided. These licenses granted companies exclusive rights to explore, drill, and produce within their blocks. The first well was drilled in 1966, but it did not yield commercially viable quantities. With the discovery of the Ekofisk field in 1969, Norway’s petroleum development truly began. In the early stages, foreign companies monopolized exploration in the North Sea and led the development of Norwegian oil and gas fields. In 1972, the principle that 50% of each oil license should be state-owned was introduced, and the state oil company Statoil was established. As production increased year by year, Statoil was privatized in 2001, but as of 2019 the state still owned 67% of the company’s shares.

Turning oil profits into the national interest: The Oil Fund

In 1990, the Norwegian government established the Oil Fund (Oljefondet) to make use of profits from the oil industry. Because its income is allocated to pensions, in 2006 the fund’s name was changed to the Government Pension Fund Global (GPF-G). As of 2021, its assets had reached USD 1 trillion.

The fund was created because oil prices are unstable. For example, if a fire occurs at an oil field somewhere in the world or a natural disaster strikes, oil prices can spike sharply, and decisions by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which manages about 80% of the world’s proven oil reserves, have a major impact on crude prices. Oil prices are also highly sensitive to the global economy and to supply and demand. In 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic caused economic activity to plunge, oil demand plummeted and, for the first time in history, oil prices fell below zero territory (※2).

The fund therefore invests part of the substantial profits from the oil industry and spends more during downturns, shielding Norway’s economy from being buffeted by global crude prices. In reality, however, as of 2019, revenue from oil and gas production accounted for less than half of the fund’s value. By investing money earned from oil into equities, bonds, real estate, renewable energy, and infrastructure around the world, the fund has diversified its income sources.

Currently, under the management of Norway’s central bank, the fund holds shares in more than 9,000 companies across 74 countries, equivalent to 1.5% of global invested assets. It also earns rental income by owning hundreds of buildings in leading cities worldwide. By diversifying its investments broadly, the fund reduces the risk of losses. The establishment of the GPF-G has contributed to the stability of Norway’s economy, and thanks to the fund, Norway has achieved a fiscal surplus every year since it first began producing oil.

Equinor, established in 1972 as a state oil company (Photo: Jørn Eriksson / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED])

The current state of the oil industry

As of 2023, 92 oil fields were in operation, and production of crude oil and other liquids was estimated at about 2.26 million barrels per day, of which about 90% is exported. In 2021, Norway exported crude oil worth 415億 US dollars, with the top destination being the United Kingdom (117億 US dollars), followed by Sweden (61億5,000万 US dollars), the Netherlands (61億2,000万 US dollars), China (61億 US dollars), and Germany (21億1,000万 US dollars).

As noted above, oil and gas fields on the NCS are indispensable to Norway’s economic development. However, in May 2021 the International Energy Agency (IEA) argued that achieving net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 would require a complete transformation of the global energy system and that no new oil or gas fields should be developed. It also stated that around 90% of global electricity generation would need to come from renewable energy, with solar and wind together accounting for nearly 70%. Norway, however, is pursuing policies that run counter to this IEA prescription. While it is true that renewables account for most electricity generation within Norway, as noted above, the crude oil and natural gas extracted in Norway are exported and consumed abroad.

Rather than reducing oil production, Norway is actually increasing it. In 2019, 57 wells were drilled and a record 83 new production licenses were issued. In 2020, after crude prices collapsed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and oil companies hesitated to invest in new drilling, the Norwegian parliament introduced temporary tax incentives to encourage oil investment.

In January 2022, the Norwegian government issued 53 new oil production licenses, and the government earned about USD 111 billion in revenue from the oil industry in a single year. In 2022, as the Russia–Ukraine war broke out and Russia reduced oil supplies, Norway overtook Russia to become Europe’s largest gas supplier.

Oil storage facility in the city of Honningsvåg (Photo: jbdodane / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED])

Balancing environmental protection

As mentioned at the outset, Norway demonstrates a proactive stance on environmental protection domestically. Offshore drilling has been subject to a carbon tax since 1991, and as of 2022 about 85% of domestic greenhouse gas emissions are covered either by the EU Emissions Trading System (EUETS) (※3) or by a carbon tax. A carbon tax is a tax levied according to the amount of carbon dioxide emitted, and its introduction is expected to discourage companies from using fossil fuels. The government’s climate action plan announced in 2021 also included further increasing the carbon tax rate imposed on offshore carbon dioxide emissions.

Norway was also the first country in the world to ratify the Paris Agreement (※4), which aims to limit global warming to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. In June 2017, the Norwegian parliament adopted a Climate Change Act that legally sets targets to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 50–55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels, and by about 90–95% by 2050 to become a low-emission society. The GPF-G is also active in environmental protection, and in 2017 it announced that it would divest oil and gas company stocks equivalent to USD 35 billion in investments.

Climate change could also negatively affect global food production. There are predictions that food production could decline by 30% by 2050. Accordingly, Norway is supporting measures such as technological innovation to improve productivity in low-income countries where undernutrition is severe.

In reality, however, doubts arise as to whether the Norwegian government is taking such measures out of a genuine desire to protect the environment. Specifically, the carbon tax applies only to emissions from domestic consumption, and when oil extracted and exported is consumed abroad, those emissions are not covered. Under the Paris Agreement as well, carbon dioxide emissions are counted where fossil fuels are consumed, not where they are extracted. This means that even though oil and natural gas exported from Norway in 2020, if burned domestically, would emit about 4億5,000万 tons of carbon dioxide—roughly 9 times Norway’s annual total emissions—Norway can still achieve net zero emissions.

Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre of Norway speaking at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) (Photo: COP26 / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

Thus, Norway appears willing to take responsibility for carbon dioxide emissions generated within its borders while setting aside concerns about the climate impact of its exported oil and gas. Furthermore, with regard to the GPF-G’s large-scale divestment of oil and gas stocks, motives other than environmental protection have also been suggested. With growing concern over environmental issues, crude oil prices are expected to decline in the future. There is thus a question as to whether the GPF-G divested out of concern that holding oil and gas company stocks would cause its own value to fall.

Also, although we noted at the outset that Norway has the highest per-capita use of electric vehicles in the world, it has been pointed out that electric vehicles do not reduce carbon dioxide emissions all that much in practice. EVs are largely made up of batteries, and mining and smelting of the raw materials used in their manufacture generate large amounts of greenhouse gases. Furthermore, if the electricity used to charge EVs is not generated from renewable energy, greenhouse gas emissions will be high.

A free parking lot reserved for electric vehicles in Oslo, the capital (Photo: Mario Duran-Ortiz / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

Other issues with the oil industry and climate measures

The problems the oil industry poses for the environment are not limited to the carbon dioxide emitted by using oil; drilling the deep seabed can also destroy marine habitats. In January 2024, the Norwegian parliament decided to open 281,000 square kilometers—an area roughly the size of mainland Norway—for exploration and development of deep-sea mining of minerals. The decision has been criticized by scientists and environmental activists. They argue that the process failed to consider the breadth of the ecosystems likely to be affected by mining. The area also includes habitats for rare species, and it is pointed out that mining residues and chemicals used in the process could spread over a vast area via ocean currents, harming these species and destroying ecosystems.

The oil industry and climate measures can also affect the lives of Indigenous peoples. Railway construction to transport oil and natural gas has taken pastureland from the Indigenous Sámi people, who have traditionally lived in the Arctic, and has cut across the reindeer migration routes they depend on. Moreover, although renewable energy and EV production are being emphasized as climate measures, these too are negatively affecting Sámi traditional life. Dams for hydropower threaten to inundate Sámi settlements and have blocked reindeer herding routes. Wind power development has also forced further loss of land as facilities are built in mountainous areas, shrinking the Sámi living space. In addition, EV production requires large amounts of mineral resources, and since mining areas overlap with Sámi territory, mining development is also impacting Sámi life.

The Norwegian parliament building in central Oslo (Photo: LH Wong / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

Outlook and conclusion

We have seen how Norway appeals to other countries and organizations that prioritize environmental protection by showcasing its proactive climate measures while at the same time remaining dependent on the oil industry.

So how do Norwegian citizens view this situation? A majority of Norwegians also seem to want the oil industry to continue. In a 2021 survey, 59% of Norwegians supported continued oil and gas exploration, while 23% were opposed. Norway’s welfare-state system—including relatively low education costs compared with other countries, full pay throughout 49 weeks of parental leave, an average life expectancy about 10 years longer than the global average, and stable pension benefits even in an aging society—has aspects that are sustained by profits from the oil industry. Therefore, not only the government but Norwegian citizens themselves benefit from the oil industry, making it difficult to let go of it.

Will Norway choose to be a leader in climate action or a leader in oil exports? A ruling handed down in January 2024 may point the way. Climate activists won a case against the Norwegian government over development plans for offshore oil and gas fields. They argued in court that the environmental impact of emissions had not been properly assessed in the Ministry of Energy’s approvals in 2021 and 2023 for the development plans of three oil fields, and that the approvals were therefore invalid. In its ruling, the court stated that the impact of emissions must be properly considered by law, and that no such assessment had been conducted in the approval process. As a result of the ruling, until the validity of the development plan approvals is legally determined, the government is prohibited from making other decisions that require valid approval of those plans, meaning that production at the fields must be halted.

Moreover, the benefits brought by oil and gas will not last forever. Reserves are finite, and 47% of the fossil fuels on the NCS have already been extracted. In light of these circumstances, will Norway pivot away from dependence on the oil industry and, as a leader in environmental protection, guide governments around the world? We will be watching future developments.

※1 “Licensing rounds” is a term referring to the competitive process by which governments or regions award rights to explore and develop new energy or mineral resources.

※2 The West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil futures price, a benchmark for U.S. crude, recorded a negative value for the first time in history on April 20, 2020, at -$37.63 per barrel. This means sellers paid buyers $37.63 per barrel to take delivery of oil.

※3 A system that sets a cap on the total amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted by sectors such as maritime transport, manufacturing, and aviation. Companies can trade emission allowances with each other as needed. The system operates in all EU member states as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

※4 The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change. It was adopted by 196 countries at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) held in Paris, France, on December 12, 2015, and entered into force on November 4, 2016. Its goal is to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and it includes all major emitters, including low-income countries.

Writer: Minori Ogawa

Graphics: Yudai Sekiguchi

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks