The term Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is well known in Japan and ubiquitous in daily life. You often see SDGs in news, variety programs, CM commercials, the activities of the national and local governments, and even around town. The volume of coverage can also be seen in the data. For example, in 2023 the number of newspaper articles containing the word “SDGs” was 183 in the Asahi Shimbun, 126 in the Mainichi Shimbun, and 220 in the Yomiuri Shimbun (※1). As such, partly due to the amount of coverage, newspaper readers’ awareness of the SDGs is extremely high at 95.3%.

While many of the world’s challenges go unreported, why do the media frame so many global and social issues through the lens of the SDGs and continue to publish so much SDGs-related content?

A banner promoting the SDGs (Photo: SDG Action Campaign / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED])

目次

SDGs late to attract media attention

So, when did the SDGs start getting attention in Japan? The SDGs were adopted unanimously by UN member states at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015. They are international goals aiming for a more sustainable and better world by 2030, comprising 17 goals and 169 targets, pledging to “leave no one behind” on Earth. First, let’s look back at the background in which the SDGs were created and how reporting came to focus on the SDGs.

Before the SDGs were set, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were established based on the UN Millennium Declaration adopted at the UN Millennium Summit in September 2000. The MDGs set eight goals to be achieved by 2015 in the development field, including “Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger,” “Achieve universal primary education,” and “Promote gender equality and empower women.” The MDGs were aimed primarily at low-income countries, and while some targets were achieved, it also became clear that people were being left behind. However, the MDGs received little attention in the Japanese media.

Starting in 2015 and taking over from the MDGs, the SDGs emphasize the aim of a more sustainable and better world, and the goals were expanded to 17, covering poverty, food and water, health care, education, gender, environmental issues, peace, and more. The SDGs include not only low-income countries but also high-income countries, stressing the role of high-income countries in global sustainability in a tightly interconnected world where low-income countries cannot be isolated.

When the SDGs were announced, they received little attention in Japan. Looking at past coverage of the SDGs in the Asahi Shimbun, the volume was very small, and SDGs only began to be covered from around 2017.

Background to the spread of the SDGs

There are various interpretations of why coverage of the SDGs spread, but rather than some major change, the following explores how multiple factors overlapped to make the media continue to focus on them today.

As the graph above shows, the small volume of coverage up to 2016 suddenly began to increase in 2017. Behind this were moves by the Japanese government. In 2016 the government established the SDGs Promotion Headquarters. In the same year, the government also unveiled the concept of “Society 5.0”. Society 5.0 is defined as the fifth new stage following the hunting, agrarian, industrial, and information societies: a human-centered society that reconciles economic growth with solutions to social challenges by using innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence.Since balancing economic development and the resolution of social issues is related to achieving the SDGs, the concept of Society 5.0 came to be used in pursuit of the SDGs.

More than anything, however, rising attention to environmental issues likely fueled interest in the SDGs. Among the SDGs targets are environmental goals such as “13. Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts,” “14. Conserve and sustainably use the oceans,” and “15. Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems.”

Behind the focus on these climate-related goals was the influence of the term “decarbonization.” In 2017, the NHK Special NHK Special “The Business Upheaval: The Shock of the ‘Decarbonization Revolution’” used the term “decarbonization,” which created a stir, and the term SDGs also appeared. The program showed how, spurred by the Paris Agreement, a new international framework for reducing greenhouse gas emissions beyond 2020, the world began moving toward a “decarbonized society” that effectively brings CO2 emissions to zero, and how global environmental efforts and business changed significantly, as well as efforts to solve social issues with Japanese technology. The linkage between the term “decarbonization” and the SDGs made an impact, and SDGs-related coverage began to increase in the media from 2017. In government, initiatives advanced on both domestic implementation and international cooperation, such as the establishment of the SDGs Promotion Headquarters, connecting the image of solving social issues with the SDGs.

Environmental moves at the central government level continued after 2017. In 2019, Shinjiro Koizumi, who is often in the news, was appointed Minister of the Environment, becoming a hot topic. Furthermore, in September 2020 Yoshihide Suga became Prime Minister and declared in his policy speech that Japan would aim for carbon neutrality, bringing total greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. At the U.S.-hosted climate summit in April 2021, Prime Minister Suga also declared that Japan would aim to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 46% in fiscal 2030 from fiscal 2013 levels. A GNV study has found that coverage of climate change actually increased across media during these periods.

Train with prominent SDGs ads (Photo: Juliet Nanami / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed])

Environmental moves involve not only politics but also major corporate influence. In April 2017, Ricoh became the first Japanese company to join RE100 (RE100), a coalition of companies aiming to power their operations with 100% renewable energy, and by March 2023, 78 Japanese companies had joined. This is the second-largest number after the U.S.’s 99 companies, and out of a total of 399 companies, it shows that Japanese firms are proactively participating.

Beyond the environment, social issues are also gaining attention in the business world and being linked to the SDGs. ESG investing, which emphasizes conducting business with consideration for society as well as appropriate corporate governance in addition to environmental issues, has become a trend in investing. ESG stands for environment, social, and governance, and ESG investment focuses on corporate sustainability as well as profits. The influence of ESG investing is significant. For example, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) manages pension reserves and handled a massive 224 trillion 7,025 billion yen in fiscal 2023, and it promotes ESG investment across the board. In this way, companies have focused on ESG and linked their business activities to the SDGs, leading them to pay attention to the SDGs and ESG on the grounds that this can enhance investment value and corporate value.

Coverage related to the SDGs appears to have increased in step with these moves. Past GNV research has also shown that reporting tends to align with political and economic elites. Initiatives related to the SDGs by central government bodies such as the Cabinet Secretariat and by large corporations have inevitably influenced the media, increasing SDGs coverage. Interest among these elites and media interest increased at the same time, and looking at the content of SDGs coverage, environmental issues account for as much as 25% of the total. While the SDGs include wide-ranging goals beyond the environment—poverty, food, water, health care, education, gender, peace—both among political and economic elites and in reporting, the way the SDGs are framed in Japan is heavily skewed toward environmental issues.

SDGs as media-company initiatives

Many news organizations appear to be committing to the SDGs not only as topics for coverage and reporting, but also as organizations themselves. For example, TBS Television has run a campaign since 2020 based on the concept of the SDGs called “WEEK to Make the Earth Smile.” Since 2021 it has set aside about one week in spring and fall for the campaign period. You can see that the company as a whole is working on the SDGs, including TBS Radio, BS-TBS, YouTube, and the social network X (formerly Twitter). Many companies support it as sponsors, including Toyota Motor, Nissan Motor, Nisshin Seifun, Seven & i Holdings, and Asahi Soft Drinks. In this way, campaigns under the SDGs banner are conducted in partnership with companies.

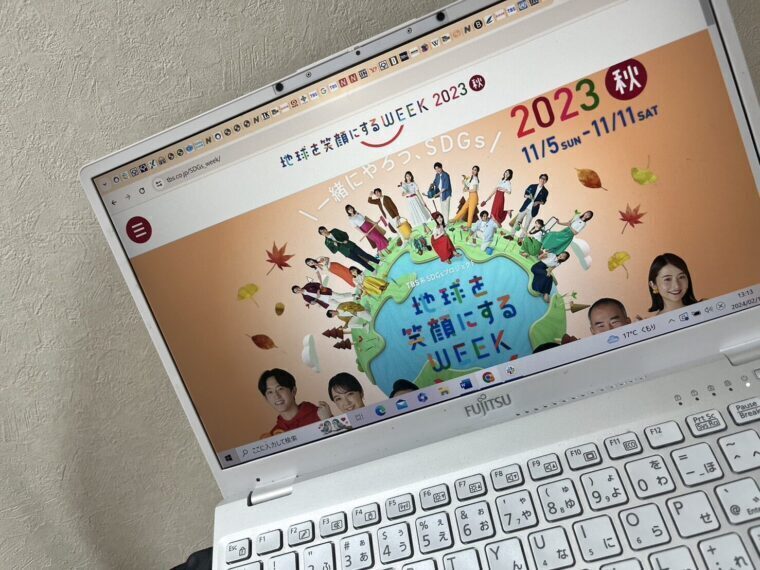

TBS website promoting the SDGs, photographed February 15, 2024 (Photo: Junpei Nishikawa)

Many media outlets have also joined the UN SDG Media Compact to demonstrate their commitment to the SDGs. The UN SDG Media Compact was established in September 2018 to mobilize the resources and creative talent of media and entertainment companies around the world to advance the achievement of the SDGs. As of January 2024, as many as 217 Japanese media companies have joined the Compact. With about 400 participating companies worldwide, Japanese companies make up roughly half.

In writing this article about the relationship between the SDGs and the media, we interviewed media professionals about why the SDGs have come to attract so much attention. According to Naoki Hashimoto, a producer at the production company “Kosoado,” which has created many climate-related programs, “the SDGs are convenient and adaptable because of the wide range of issues they cover.” In other words, dealing with the SDGs not only allows work on environmental issues but can also be applied to all kinds of social issues. He also said that because “the UN is promoting the initiative, it gives the impression of high credibility” in relation to the SDGs, making it easier for media organizations to promote them and creating an environment in which the media can readily engage with the SDGs.

SDGs that attract companies

We noted in the previous section that companies are committing to the SDGs, but what specific benefits do they gain? For commercial media, the SDGs are not just a subject of coverage; they also need to attract corporate sponsors, and the SDGsという概念 is being used as part of that effort. Here we look at the background behind continued SDGs coverage.

Today, environmental and gender issues related to the SDGs are often covered, but it used to be said in the TV industry that such issues did not draw ratings well. Regarding environmental issues, one reason cited among media professionals is that disasters occur routinely in Japan compared to other countries, so awareness of climate change is perceived to be low. Looking back at the media’s stance on environmental issues, there were periods of heightened attention in the 2000s, such as following the Kyoto Protocol established in 1997, the 2005 Aichi Expo, and the 2008 Toyako Summit. However, they did not lead to sustained momentum like the current SDGs boom.

So why are the SDGs booming now? “Because the needs of companies that want to ‘clearly’ promote their environmental efforts and the needs of the media that want to ‘clearly’ convey complex issues like climate change, which are hard to capture viewers’ interest, are aligned,” says Hashimoto. Let’s touch on the relationship between media and sponsors, namely CM contracts on television. As noted with the many sponsors of TBS’s SDGs WEEK, many companies become sponsors of media that feature the SDGs. On this, Hashimoto says, “By becoming a sponsor and airing commercials, companies can give viewers a favorable impression that they are working on the SDGs.”

SDGs badge (Photo: JuliaC2006 / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 DEED])

Given that viewers more often receive information from TV CM advertisements than from companies’ SDGs-specific pages or their products and services themselves, TV CM is an efficient way to build corporate image. Having corporate SDGs initiatives known by viewers—and society—has various benefits. For example, it can appeal to ESG investors. Not only investee companies but also securities firms are promoting this, with Nomura Securities releasing a CM about investing in sustainable companies. There are also results showing that, as with the SDGs, the most common channel for awareness of ESG initiatives is media programs and articles, again indicating the strong influence of the media.

In addition, the share of consumers who took action after learning about companies’ SDGs and ESG initiatives via the media is as high as 43.8% , suggesting that it is important for companies’ initiatives to be publicized through the media. Thus, the benefits to companies of sponsoring media that cover the SDGs are significant, and the structure in which media coverage of the SDGs helps sell CM slots is likely to continue for some time.

SDGs as off-air business

In recent years, there has been a trend that TV stations cannot survive on TV programming alone, and the SDGs have gained attention as a tool for new businesses outside broadcasting. In fact, TV Tokyo Holdings reported a 33.6% year-on-year decline in operating profit for the April–September 2019 fiscal period and announced it would increase non-broadcast revenue. As television’s position as a medium has changed, business models that relied on ratings and advertising revenue have gradually become less viable, and generating non-broadcast revenue has become a common challenge for the TV industry. How do the SDGs connect to off-air business?

Broadcasters build unique identities through ties with their local communities. There are cases of building connections with municipalities. While the link between the SDGs and business may not be immediately obvious, Fuminori Murase, a producer at Nagoya Broadcasting Network (Nagoya TV), notes that “the role of the media and the intentions of the administration aligned,” and that by hoisting the SDGs as a “signboard,” they are rolling out various projects. For example, in 2023 Nagoya TV held an event themed on multicultural coexistence by taking a music program on the road and staging it at a cultural hall. In this way, the company links local events to the SDGs to appeal to society. The central government also allocated 200 million yen in the FY 2021 draft budget to a “Regional Information Dissemination Capacity Enhancement Project” for producing and disseminating content that promotes Japan’s attractiveness through collaboration between broadcasters and local governments and local industries.

Off-air business is not limited to relationships with municipalities. Based on the shared aspiration and the concept of empathy linked to the SDGs, new partnerships have been built, including with other industries. Going beyond the traditional broadcasting framework, they are exploring possibilities for new businesses such as trading-company-like operations. There are numerous other examples of off-air businesses.

Scene from an SDGs event (Photo: SDG Action Campaign / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED])

Conclusion

As we have seen, behind the continued SDGs coverage are the convenience of the term “SDGs” and benefits to both media organizations and companies, and of course parts linked to reader and viewer demand. For example, among media outlets aimed at young people, who are said to have high interest in the SDGs, some feature the SDGs prominently. However, looking across how the SDGs rose within Japanese reporting, there has been a process of creating demand even before media and companies responded to it.

Furthermore, it appears that society sees advantages in the concept of the SDGs rather than actually working toward achieving the goals. Although the SDGs address issues affecting the entire world, Japanese reporting is almost entirely limited to domestic matters. There are also not a few cases of activities that predate the SDGs being retrofitted into the SDGs framework. For these reasons, while media and corporate advertising overflow with the SDGs, “SDGs-washing” (※2)—making it look like one is working on the SDGs despite lacking substance—stands out.

In reality, the prospects for achieving the SDGs by 2030 are extremely low. We should critically examine what is happening in the world alongside what is being reported.

※1 Searched for “SDGs” as a string appearing in headlines and body text for the period from January 1, 2023 to December 31, 2023.

Using Maisaku, Asahi Shimbun Cross Search, and Yomidas.

※2 Making it appear that one is working on the SDGs despite lacking substance.

Writer: Junpei Nishikawa

0 Comments