On December 1, 2022, a boat carrying about 180 Rohingya refugees (※1) departed Bangladesh bound for Indonesia. Aboard were also pregnant women and children fleeing poor conditions and violence in refugee camps in Bangladesh. However, a week later, the boat encountered a storm in the Bay of Bengal and sank, and the passengers’ whereabouts remain unknown.

A human rights advocacy group has argued that this incident is a prime example of governments’ inaction toward Rohingya refugees and the world’s indifference. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) stated that it has asked for the rescue of boats attempting to cross from Bangladesh to Southeast Asia via the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, but these requests have been ignored.

As we consider refugee responses in Southeast Asia, there is a fact to note: among the Southeast Asia 11 countries (※2), only the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Convention) and the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (1967 Protocol)—collectively called the “Refugee Convention”—have been ratified by just 3 countries: the Philippines, Cambodia, and Timor-Leste. This article looks at the current state of refugees in Southeast Asia and the measures in place.

Malaysian flag displayed at a Rohingya refugee’s home in Kuala Lumpur (Photo: Overseas Development Institute / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Overview of refugees in Southeast Asia

We should organize the discussion of refugees arising in Southeast Asia and those entering the region. Historically, in the 1970s, armed conflicts in the three Indochinese countries (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia) (※3), U.S. military intervention, and subsequent transitions to socialist systems produced many refugees. Refugees also arose from the conflict between the Myanmar government and anti-government forces refugees and from Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor, which produced many refugees from East Timor.

From the 1980s onward, refugees generated by the conflict between Tamil groups (※4) and the Sri Lankan government and by the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan conflict also flowed into Southeast Asia. Since 2000, refugees have emerged from the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. In the 2010s, in addition to refugees from the conflict in Syria, many Rohingya refugees have fled following violent repression by the Myanmar government. Thus, Southeast Asia has also come to receive refugees from conflicts outside the region.

With this history in mind, we summarize where large inflows of refugees into Southeast Asia are coming from today. First are refugees from Myanmar, especially Rohingya refugees, who make up the majority. Next are Afghan refugees, driven not only by prolonged armed conflict but also by the Taliban’s return to power. Others include people fleeing armed conflict and oppression in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia. Some have aimed to reach Southeast Asia, while others are refugees seeking to reach Australia via Southeast Asia.

Next, we look at the number of refugees residing in Southeast Asian countries.

This compares, by country, the number of refugees accepted by Southeast Asian countries in 2022. As the chart shows, non-parties Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia have accepted more refugees than the Philippines and Cambodia, which have ratified the Refugee Convention. Below, we detail the current state of these admissions.

Refugee policies of countries that have ratified the Refugee Convention and their issues

We now look at refugee policies in the three countries that have ratified both the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol: the Philippines, Cambodia, and Timor-Leste. First, we should confirm the role of the Convention and Protocol. According to the UNHCR, the Refugee Convention was adopted “based on the recognition that international cooperation and solidarity are crucial to ensuring the protection of refugees and resolving their problems.” The Convention enshrines a principle that refugees must not be refused entry or returned to a country where their lives would be at risk; this is known as the principle of non-refoulement. As this principle is customary international law, countries cannot return refugees or asylum seekers abroad simply because they are not parties to the Convention.

We also note the difference between the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol. The 1951 Convention sets out the definition of “refugee,” an overview of their rights, and the obligations of refugees upon entry, and applies only to those who became refugees due to events occurring before January 1, 1951. By contrast, the 1967 Protocol provides that the Convention also applies to those who became refugees due to events after January 1, 1951. The 1967 Protocol was adopted to extend the Convention to those who became refugees due to new circumstances after the Convention’s adoption.

First, the Philippines. Having ratified the Refugee Convention in 1981, the Philippines in the past accepted refugees from Indochina and the Iranian Revolution. In 2021, it decided to accept Afghan refugees fleeing Taliban rule, but a few weeks later the government announced a policy of accepting asylum applications from people fleeing Afghanistan only through official requests made by foreign governments. As the acceptance of Afghan refugees was based on a request from the United States, the decision to decline asylum requests from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other non-state actors sparked controversy.

As of 2022, 856 refugees and 780 asylum seekers (※5) were residing in the Philippines. In 2022, it accepted 59 applications as new asylum claims. Most of these were from Middle Eastern countries such as Yemen and Syria.

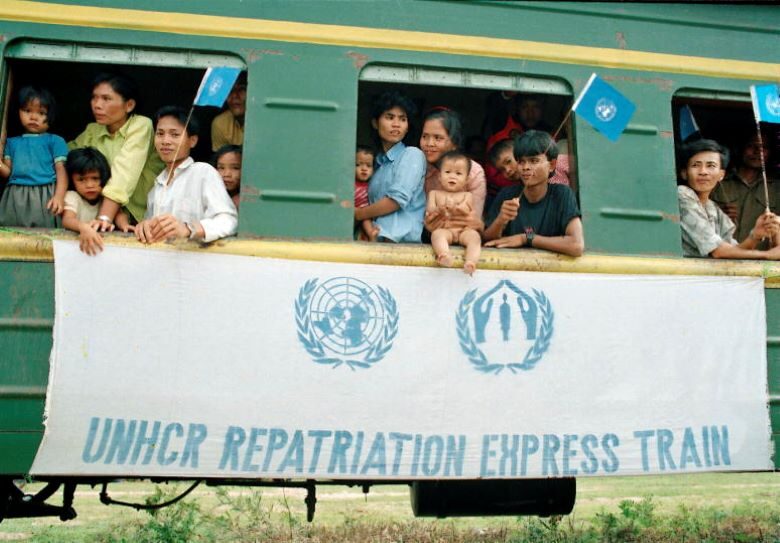

Cambodians returning from a refugee camp on a UNHCR train (1992) (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Next is Cambodia. Cambodia has a history of producing many refugees due to the U.S. incursion in 1970, the rise of the Khmer Rouge in 1975, Vietnam’s invasion in 1978, and conflicts after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Now as a receiving country: Cambodia ratified the Refugee Convention in 1992, but has comparatively accepted few refugees. Its agreement in 2014 with Australia to resettle asylum seekers who had arrived in Australia in exchange for financial support stirred controversy. There is also the fact that many refugees who had entered Cambodia were forcibly returned to their countries of origin by Cambodian authorities in 2020. In 2021, the Cambodian government stated it had agreed to grant temporary protection to up to 300 Afghan refugees while they completed procedures for third-country resettlement (※5). As of 2022, 24 refugees and 12 asylum seekers were residing in Cambodia.

Lastly, Timor-Leste. Formerly a Portuguese colony, Timor-Leste was invaded by Indonesia in 1975, producing many refugees at that time. In 1999, a referendum led to independence from Indonesia. Timor-Leste has a history in which many people experienced being refugees. In light of this, under a pledge to continue assisting asylum seekers arriving in the country after independence, it ratified the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol. This occurred in 2003, one year after the declaration of independence in 2002.

However, according to those who attempted to apply for asylum, the government of Timor-Leste was not prepared to accept asylum seekers, and some were advised instead to leave Timor-Leste. The country’s immigration and asylum law has also been criticized for a provision requiring those seeking asylum upon entry to submit their application within 72 hours of arrival.

Refugee policies of countries that have not ratified the Refugee Convention and their issues

As the graph on refugee admissions shows, not having ratified the Refugee Convention does not mean these countries do not accept refugees. In fact, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia together hosted 289,000 refugees and asylum seekers in 2021 living there. Here we focus on the refugee policies of Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia, which are among the principal receiving countries in Southeast Asia.

First, Malaysia. Among Southeast Asian countries, Malaysia hosts the largest number of refugees and asylum seekers. As of 2023, a total of about 181,300 refugees and asylum seekers reside in the country. Of these, most are from Myanmar, including many Rohingya refugees, accounting for about 86% of the total. However, according to Human Rights Watch, a surge in summary deportations of asylum seekers to Myanmar by Malaysian authorities has been observed. It has been suggested that the lack of ratification of the Refugee Convention is a major factor, along with rising xenophobic sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As of 2022, Thailand hosted a total of about 95,398 refugees and asylum seekers, mainly ethnic minorities from Myanmar. This reflects the long-standing persecution of minority groups in eastern and northern Myanmar by the government, the formation of anti-government forces, and the resulting conflicts that have produced refugees.

Thailand faces issues concerning refugees living in urban areas outside camps. Urban refugees are not recognized as refugees by the Thai government, leaving them in precarious situations and at risk of arrest and deportation. In addition, while the majority of refugees apply for third-country resettlement, the process takes a long time, leading to years of life in refugee camps.

Recent shifts are visible in Thailand’s refugee policy. One is the partnerships (※8) it has concluded with organizations such as UNHCR, based on the “Global Compact on Refugees” (※7) adopted by the UN General Assembly in December 2018. Another is that following the May 2023 general election for the lower house, in which the Move Forward Party won and became the largest party, its leader, Pita Limjaroenrat, stated an intention to sign and ratify the 1951 Convention to promote refugee protection. Changes in Thailand’s refugee policy are eagerly anticipated.

Umpiem refugee camp in Thailand (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Lastly, Indonesia. As of 2022, Indonesia hosted about 12,616 refugees and asylum seekers, about 55% of whom were from Afghanistan. Many of these refugees temporarily stay in Indonesia as a transit point to reach countries such as Australia. However, Australia’s policy of turning back asylum seekers has forced many to remain in Indonesia. Over the past 10 years, the number of Rohingya refugees seeking asylum in Indonesia has also increased by the hundreds.

Conclusion

We have examined the current state of refugee admission policies and their issues in each country. Regardless of whether they have ratified the Refugee Convention, there appear to be many unresolved challenges in Southeast Asian countries, particularly concerning the protection of refugees’ rights. In fact, in host countries, many aspects of refugees’ rights remain unprotected. Many refugees live in poor conditions, including in refugee camps. In addition, they often cannot access education or adequate healthcare or work, and face various risks such as deportation due to their legal status as “undocumented migrants.” From an education perspective, even without ratifying the Refugee Convention, any country that has ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (※9) is obliged to cooperate with the UN to protect the rights of refugee children. However, Thailand is the only state party that has entered a reservation to Article 22 (※10) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

What, then, of the refugee policy within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)? There are no ASEAN-wide rules on refugee policy; policies and laws concerning refugees are left to national governments. One view holds that this is due to ASEAN’s emphasis on respect for national sovereignty and the principle of non-interference. The absence of a legal framework for refugee protection within ASEAN may, in effect, result in national laws in Southeast Asia that insufficiently guarantee refugees’ rights.

Looking across refugee issues in Southeast Asia, legal frameworks such as the Refugee Convention, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and regional initiatives are important, but the question is how far their provisions will be implemented in practice. Attention should be paid to how refugee policies in Southeast Asian countries evolve in the future.

Rohingya refugees in Malaysia (Photo: Overseas Development Institute / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

※1 A Muslim minority persecuted in Myanmar. Following severe violent repression by the Myanmar government in 2017, many Rohingya fled to Bangladesh; as of February 2023, their number had reached about 957,971, and some Rohingya refugees attempt to seek asylum in Southeast Asia by boat from camps in Bangladesh.

※2 Here, Southeast Asia is taken to comprise the 11 countries of Indonesia, Cambodia, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, the Philippines, Brunei, Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Laos.

※3 Refugees who fled armed conflicts and military intervention by the U.S. and others in the three Indochinese countries (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia) in 1975.

※4 A Tamil-speaking ethnic group that in 1976 established the armed organization known as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) founded in Sri Lanka.

※5 Refers to people who have left their country and are seeking protection from persecution or human rights violations in another country but have not yet been legally recognized as refugees and are awaiting a decision on their asylum application refers to.

※6 Moving from the country where a refugee first sought protection to a third country that has agreed to admit them.

※7 An international arrangement aimed at promoting refugee protection through a whole-of-society approach, in which diverse actors cooperate together worldwide.

※8 By strengthening partnerships with various actors, including NGOs and private companies, the Thai government receives support from these organizations in responding to refugee issues.

※9 A treaty established to guarantee the fundamental human rights of children under 18 internationally.

※10 Article 22, paragraph 1 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child: “States Parties shall take appropriate measures to ensure that a child who is seeking refugee status or who is considered a refugee in accordance with applicable international or domestic law and procedures shall, whether unaccompanied or accompanied by his or her parents or by any other person, receive appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance in the enjoyment of applicable rights set forth in this Convention and in other international human rights or humanitarian instruments to which the said States are Parties.” Entering a reservation to this article means that refugee children in that country may not be able to receive adequate education.

Writer: Hayato Ishimoto

Graphics: Ayane Ishida

確かにASEANとしての難民政策の指針が定まっていないのは、難民問題を負のスパイラル化させる要因になりうりますね。

難民問題は、市民と政治家とで大きく乖離しやすい分野でしょう。きっと、政権担当者としては、建前では「難民の権利や命を救う」という人道的な理由を掲げているとは思いますが、その裏には実績のアピールとして利用している面もあるのではないでしょうか。

しかしながら、実際に難民受け入れの弊害を被るのは我々市民ですから、それが賛成であろうと反対であろうとその国の難民政策は、国民の総意に委ねられるべきでしょう。

ヨーロッパでの移民・難民船の難破問題もよく聞きますし、東南アジアに限らず世界的に難民の問題は見られますね。難民を無条件に大量に受け入れれば解決する問題でもないので、難しいですね。

東南アジアではこれほど難民を受け入れていたことにまず驚きました。そして、それにもかかわらずルール作りがしっかりとは行われておらず、実害が起こり始めているのはその国の市民たちがかわいそうだなと思いました。難しいとは思いますが、ぜひとも難民を今後も受け入れつつ地元の人たちが損をしないようなルール作りをしてほしいなと思います。

最近日本でも海外出身の人間による犯罪が少し目立ってきて、治安が乱されていると感じるので、難民の受け入れや海外からの人口の流入についてもこの東南アジアの例を参考にして、しっかりとした、日本人が損をしないようなルール作りをしてほしいなと感じました。

ロヒンギャ難民、バングラデシュだけじゃなくて東南アジアにも及ぶんですね。。