From orchestras and wind bands to rock and pop music and traditional music around the world, much of music exists alongside instruments. When we look at what those instruments are made of and how those materials are procured, we can see the connections between instruments that produce beautiful tones and the wider world. And among the raw materials for these instruments, many are sourced from Africa.

At GNV, we have repeatedly reported on issues of global resource development and exploitation. In particular, we have focused on products exported from Africa that enrich people’s lives around the world, such as tea and coffee, foods like chocolate, and mineral resources. This time, as resources that make instrument manufacturing possible and their links to the world, we take a closer look at two materials: ivory and African blackwood.

A herd of African elephants (Photo: Ray in Manila / Wikimedia [CC BY 2.0])

目次

Ivory and the decline of elephants

The connection between instruments and Africa cannot be told without the dark and tragic history of ivory. Ivory refers to the large tusks protruding from an elephant’s mouth. These teeth have basically the same structure as human teeth, with an outer enamel covering the dentin known as ivory. For elephants, tusks are a body part with various functions such as digging holes, lifting objects, and gathering food. To remove ivory from an elephant, one would need to perform highly complex dental surgery or kill the elephant. Therefore, when ivory is traded commercially, people have obtained it by killing elephants rather than undertaking costly and time-consuming surgery.

This has affected elephant population declines. It is said there were 25 million African elephants in the 1500s, but by the 1900s their number had fallen to 10 million, and by 1979 it had decreased to 1.3 million (※1). The decline did not stop thereafter; by 1995, numbers had fallen to around 280,000. Poaching had a major impact on the rapid decline from the late 1970s onward, and numbers plummeted even in protected areas such as national parks. In response to this decline, a 1996 assessment listed the African elephant as threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List, which classifies species at high risk of global extinction.

A pile of ivory (Photo: U.S. Government / RawPixel [Public domain])

In response to the series of declines in African elephant populations, the Washington Convention (CITES: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) banned the international commercial trade in ivory in 1989. However, domestic trade remained legal in some countries. After recommendations to suspend domestic trade were issued in 2016, ivory-consuming countries such as the United States, Thailand, Taiwan, China, and Hong Kong moved to legally prohibit domestic trade. In Japan, however, ivory transactions have continued legally under certain conditions, such as tusks from naturally deceased individuals. Although there were some exceptions, CITES regulation of international trade in ivory once seemed to stabilize elephant numbers and improve the situation. Yet in the 2010s, poaching surged again, and it is estimated that approximately 15,000 elephants are killed annually. IUCN’s 2020 reassessment also pointed to ongoing declines, and African elephants remain at risk of extinction.

Ivory and the piano

What does ivory end up becoming? In addition to carved ornamental objects, ivory has been used for accessories such as necklaces and bangles, seals and netsuke, and items like dominoes and mahjong tiles. Today, ivory may be associated with high popularity and high levels of trade in Asian countries, but in fact, from around 1840 to 1940 the world’s largest buyer of ivory was the United States. The 1800s to 1900s were also the period when elephant numbers declined sharply. What was ivory used for in America during that time?

Ivory exported to the United States in that period was turned into various items such as billiard balls, cutlery handles, and buttons. In the 1800s, the piano emerged and came to be placed in parlors of middle-class homes as a symbol of prosperity and culture. Following the French Revolution of 1789, demand for music among the general public rose in Europe and the United States, and the industrialization of piano production progressed, leading to mass production. The spread of the piano came to occupy a central place in the ivory trade and processing in the United States.

A piano with ivory used on the keys (Photo: Graham / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

A standard piano keyboard is divided into white keys and black keys. On modern pianos, white keys are used for the natural notes and black keys for accidentals (notes with ♯ or ♭). However, in 18th-century pianos, the arrangement of white and black keys was the reverse of what it is today. In other words, on early pianos, black keys were used for the natural notes and white keys for the accidentals. There are various theories as to why the colors were reversed, one being that cost could be reduced by using expensive ivory for the smaller accidental keys and ebony for the larger natural-note keys. In the 19th century, however, the positions of the white and black keys were switched. Explanations include that pianos with more white surface area were visually brighter and preferred, and that pianos that used lavish amounts of costly ivory on the natural notes came to be favored as a symbol of wealth. Moreover, ivory was considered an ideal material for keytops and preferred by many players: its surface is covered with pores, offering just the right balance of glide and grip for the fingertips, enabling fast passagework and a satisfying playing feel.

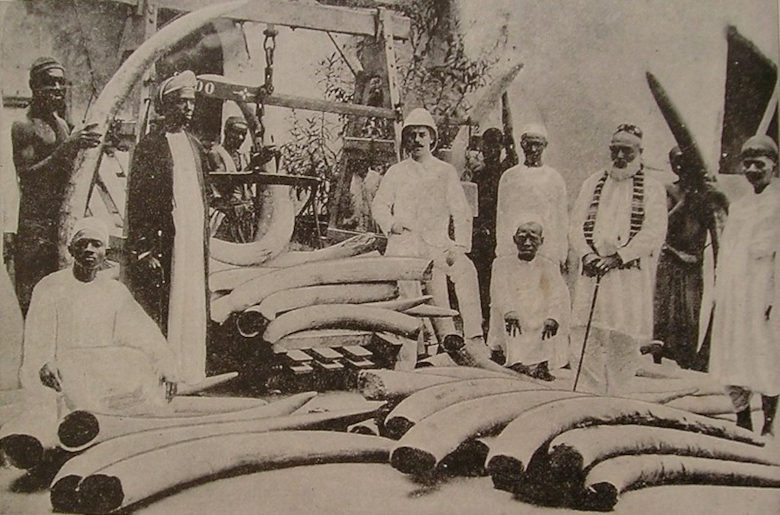

The use of African ivory in a piano that developed in Western Europe was also a result of expansion into Africa and exploitation across the continent through colonial policies. We must not forget the people forced into slavery for the ivory trade used in pianos. The island of Zanzibar off Tanzania was a hub for buying and selling ivory and for the trafficking of enslaved people. Traders whose livelihoods depended on the ivory trade and human trafficking regularly headed into the African interior, raiding villages to secure ivory and inhabitants. Among those captured, adult men were forced to carry ivory from the interior to the coast. The journey was extremely harsh; in some cases, only one in four survived. Such brutal treatment of people enslaved in the African interior continued until the mid-1870s.

European traders with ivory, 1898 (Photo: bunky’s pickle / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

At that time, the world’s largest producer of ivory goods was the Pratt, Read Company in Connecticut, USA. As pianos spread, the company improved its ivory-cutting machines for piano key manufacture. In the first decade of the 20th century, more than 350,000 pianos were produced annually in the United States, and most keytops were made by just two companies: Pratt, Read and Comstock, Cheney. This was twice the annual production of Germany, which had the second-largest piano industry. A standard 88-key piano has 52 white keys and 36 black keys. Since one tusk could yield 45 keytops, a little more than one tusk was needed per piano. Simple arithmetic thus suggests that over 1.75 million elephants were killed for pianos in the first decade of the 20th century. Some experts have estimated that between 1860 and 1890, between 25,000 and 1,000,000 elephants per year were killed for ivory, most of it used in piano manufacturing—evidence that the histories of ivory and piano making are inseparable. As ivory prices rose in the mid-1950s, plastic keytops were adopted, bringing an end to the manufacture of new ivory keytops. Today, artificial ivory and acrylic sheets are used.

African blackwood and woodwind instruments

The ban on commercial ivory trade did not end the relationship between instrument making and Africa. A material inextricably linked to Africa today is African blackwood (hereafter AB wood), used as a raw material for woodwind instruments.

AB wood, also known as grenadilla or African ebony, is a leguminous tree called mpingo in Swahili. While “grenadilla” is commonly used in the wind instrument industry, it originally referred to a different species, cocuswood. Around 1900, as cocuswood became difficult to obtain and AB wood replaced cocuswood in wind instrument manufacture, AB wood came to be called grenadilla. AB wood grows from dry savanna regions into Central and Southern Africa. It was once widely distributed from Senegal to Ethiopia and South Africa, but logging reduced its numbers; today its main range is in southeastern Tanzania and northern Mozambique. As its name suggests, the heartwood is black, very dense, and sinks in water, and it is said to take about 70 to 100 years to reach harvestable size. AB wood is used mainly for woodwinds—the clarinet family (※2), the oboe family (※3), and also for piccolos.

African blackwood tree with bean pods (Photo: SAplants / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

One reason AB wood is used for woodwind manufacture is that instruments such as the clarinet and oboe have complex key systems. A key system is the set of levers and plates used to operate the many tone holes drilled in the body. The clarinet, derived from the single-reed instrument chalumeau that looks like a recorder, evolved by adding tone holes to expand its range and facilitate chromatic playing. To close the increased number of holes, a key system was developed, yielding the modern form. The widely used Boehm-system clarinet was completed in the 19th century by Hyacinthe Klosé. AB wood was adopted because it has sufficient hardness to support the multiple keys required to cover the added tone holes.

Although the clarinet was developed and manufactured in Europe (France, Germany, etc.), the use of an African wood for the body reflects the resource extraction carried out by Western powers under colonialism as they expanded into Africa. Under colonial policies, Western powers carried out extensive logging across Africa. This overexploitation of forests not only failed to bring economic benefits to producing regions, it also pushed numerous tree species to the brink of extinction and increased the scarcity of species capable of yielding high-quality timber today. AB wood was introduced to Europe during this period. In the 19th century, AB wood came to be used for woodwind bodies in place of traditional materials such as boxwood.

An oboe with a complex key system (Photo: quack.a.duck / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Problems surrounding African blackwood

In the 1960s, as African nations achieved independence one after another, direct colonial rule seemed to end. However, AB wood is still imported mainly from Tanzania and Mozambique for use in woodwinds. Here we consider issues surrounding AB wood from the perspectives of waste in manufacturing, illegal logging, and economic returns to producing communities.

AB wood is criticized for being wasteful in its manufacturing process. Because AB trees grow with twists and branches, it is difficult to harvest wood suitable for wind instrument manufacture. Moreover, to ensure stable pitch and tone, the material must be turned down uniformly, selecting sections free of twists, knots, and cracks. As a result, 90% of the timber is discarded at the sawing stage, and a further 20% is lost during machining processes at manufacturers’ factories.

In addition, AB wood’s actual export volume greatly exceeds official export figures, suggesting a high possibility of unrecorded felling—i.e., illegal logging—has been indicated. In Tanzania, one of the AB wood range countries, data suggests that 96% may be illegally logged, and the fact that volumes used by the instrument industry alone exceed official exports supports the possibility of illegal logging. In IUCN’s 2020 assessment, AB wood is classified as Near Threatened, with a decline of 20% to 30% over the past 150 years. Near Threatened is defined as “a species that does not currently qualify for the threatened categories but is close to or likely to qualify in the near future depending on changes in its habitat conditions.” Countermeasures are urgent before the situation becomes irreversible.

Although AB wood is said to be among the most expensive woods in the world, producing communities often do not earn sufficient income. In an environment rife with illegal logging, producers who evade price regulations compete against one another, and communities in AB-producing regions may not fully recognize its true value. As a result, AB wood may be sold below its real market value, or buyers may force down prices.

In Tanzania, a producer country, under a mechanism called Participatory Forest Management (PFM), communities can designate Village Land Forest Reserves (VLFRs) and hold the right to receive revenue from forest resources. In areas where VLFRs have been established, income has reportedly increased by 40,000%, and profits from timber production outside VLFRs are minimal. While VLFRs hold high promise for returning forestry profits to communities, the registration procedures are complex, and few communities are able to make use of them.

Processed African blackwood (Photo: Rob Campbell / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

AB wood is processed not only into instruments but also into crafts and furniture, among other uses. However, there is a view that woodwind manufacture is its primary destination, and the instrument industry bears responsibility for conserving AB wood and returning benefits to communities. Major clarinet makers have put forward their own initiatives. For example, the France-based Buffet Crampon Group has developed a new material recomposed from AB wood powder as part of an effort to use recycled wood, and it has announced that most of its raw material is sourced from forests certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). Japan-based Yamaha Corporation is also working on reforestation of AB wood and improving wood utilization rates. However, the former still manufactures clarinets from AB wood, and even if most of the AB wood is FSC-certified, not all of it is. As for the latter, it takes 70 to 100 years for newly planted trees to reach sufficient size, so continuous activity is essential for meaningful impact. At this point, it is difficult to accurately evaluate how far these efforts will go toward solving the root problems.

Instruments and the world, connected even further

People around the world enjoy playing instruments and listening to music. If we look at where the materials that create beautiful tones come from and the histories they have traveled, we find that music is also tied to a history and reality of resource exploitation. Focusing on two materials—ivory and AB wood—we have examined the relationship between resources exported from the African continent and musical instruments.

Broadening the perspective reveals even more varied materials and connections between instruments and the world. For example, rosewood, which is globally threatened with extinction, is also used as a raw material for instruments. Among them, Honduran rosewood is used in marimbas, a keyboard percussion instrument, and in guitars; the wood used for marimba making is said to come from trees 200 to 400 years old. In IUCN’s 2019 Red List, Honduran rosewood is assessed as in a state of “Critically Endangered,” facing an “extremely high risk of extinction in the wild.” Furthermore, among rosewoods, the Brazilian rosewood and the Madagascar rosewood, famous as premium materials for classical guitars, are also in perilous condition.

A rosewood guitar neck (Photo: Rick Mariner at HaywireGuitars / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Moreover, although the quantities used in the instrument industry are limited compared with industrial products, minerals are also used in instruments. Copper and zinc, the raw materials for brass alloys used in pianos and brass instruments, and gold, silver, and nickel used in instrument materials and plating, are sourced from around the world. The mining and trade of mineral resources pose problems such as environmental destruction and “tax saving” via tax havens, which prevents profits from being returned to producing countries.

In this way, the instruments that support the enjoyment of music are made possible by global resource development, and companies that make instruments, performers, and those who enjoy music need to take the associated issues seriously. As seen in the cases of ivory and AB wood, the impacts on local communities and people cannot be ignored. These facts may be uncomfortable for those who wish to enjoy music “purely.” Nevertheless, we ask that you confront these inconvenient facts sincerely and reconsider our connections with the world.

※1 There are two major types of elephants: African and Asian. This article does not address Asian elephants. Although Asian elephants are said to be less affected by ivory poaching than African elephants, habitat loss and other factors are impacting their population decline. On the IUCN Red List, they are classified as “Endangered.”

※2 Members of the clarinet family include: C clarinet, B♭ clarinet, A clarinet, E♭ clarinet, alto clarinet, basset horn, bass clarinet, contra-alto clarinet, contrabass clarinet

※3 Members of the oboe family include: oboe musette, C oboe, A oboe, English horn, bass oboe

Writer: Azusa Iwane

0 Comments